Those who are smart and protecting themselves need to continue doing their best to protect themselves and their loved ones.

I found this in a comment on a friend's Facebook post. One advantage of information overload is that such comments quickly become "anonymized information" in my brain, protecting the innocent and the guilty alike.

What struck me about this statement, with which I heartily agree, is what it tells me about how much we are alike. We all want to protect ourselves and our loved ones, and most of us have opinions as to how best to do that.

It is in the means, not the ends, that we disagree.

Some people move to rural areas and learn to farm. Some organize and join unions. Some purchase and learn to use guns. Others choose to homeschool, or to take political action, or to stockpile food and other essentials. Some work hard to strengthen family and community ties, or to attend to their own physical fitness, or to build up a strong financial base. And some people get vaccinated against COVID-19. Many choose more than one of these paths.

The writer of the Facebook comment was specifically speaking of COVID-19 vaccination, which I certainly consider to be a valid way of choosing to protect oneself and one's family. Unfortunately, the context of the above quotation wasn't as reasonable.

I know this is callous, but those who are smart and protecting themselves need to continue doing their best to protect themselves and their loved ones. What happens to those who do not care, is no longer taking up my headspace.

Just as the excerpt epitomizes what we have in common, the context shows what is dividing us. Because by "those who do not care," the writer appears to mean those who choose not to follow his own particular choices. Possibly, he's expressing his willingness to leave them alone to make their own decisions. But the callousness, which he admits, contains the implication that he considers doing them harm to be a valid part of protecting himself.

That is very dangerous ground indeed. We can do better.

Permalink | Read 1059 times | Comments (0)

Category Hurricanes and Such: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Health: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Politics: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Random Musings: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

"Find Your ZZZs: How to Get the Best Sleep Every Night"

It was a two-page article in our local city newspaper—and very large print at that. So I certainly couldn't have expected anything profound. I'm only calling it out because I was struck by how inapplicable it was to me. The advice given must work for many people, because I've heard it in just about every article I've read about sleep. But one size simply doesn't fit all, and I wish that were more universally acknowledged. Here's some of the advice given:

- Set your bedtime so that you wake up at the end of a 90-minute sleep cycle Not applicable, since I'm one of the blessed people who almost never uses an alarm clock. I wake up when I wake up, and figure there's no need to worry about sleep cycles.

- 30 minutes to an hour before bedtime, turn off bright lights and put devices away "Avoiding screen time at least 30 minutes before bed is critical to your quality of sleep." That's a very common recommendation, but for me just a few minutes of reading or doing puzzles in bed is the best trick I've found for putting me right to sleep, and it doesn't matter a bit whether they're print or electronic.

- Decrease the amount of disruptive light in the room with blackout curtains or a sleep mask. This might actually be useful. Light doesn't keep me from falling asleep, but our neighbor's bright, motion-activated light does wake me up and make me wonder which of our wild animals is dancing on the lawn.

- Keep your room a cool temperature (experts suggest between 60 and 67 degrees) Right. Maybe that works for a northerner, but running the A/C that much is not in our budget. Besides, at that temperature, I'd be wearing my winter pajamas and huddling under the blankets.

- Invest in your sleep with a supportive bed and comfortable bedding You mean the mattress and box springs we got second-hand from my in-laws almost 20 years ago should be replaced? At least the author had the grace to admit that "upfront costs of a new bed may be intimidating"—as we re-discover every time we think we might do just that.

- Don't use the snooze button Not a problem, since I'm not using an alarm clock.

- Expose yourself to sunlight when you get up Hmm. I think not. Since I'm usually up a couple of hours before sunrise, that's not going to happen; it's especially hard during Daylight Saving Time.

I'm not complaining; I'm sure the article was helpful for some folks. But I do find that more and more these days people are over-generalizing when it comes to what other people are like. I guess we just need to be more aware of what truly works for us and not worry about what other people think.

Actually, I do have one complaint, I suppose: With all that advice about going to bed and waking up, they did not address the only trouble I do have with sleeping: getting back to sleep after awakening in the middle of the night! Praying is the best help with that—but only memorized prayers; if I have to think to any extent it only speeds the squirrel-wheel in my brain.

I know I'm a little late for this Thanksgiving wish, since we're now well into Advent and the rest of the country is singing Christmas carols and concentrating on commerce. But on the real Thanksgiving Day we were far too busy indulging in our family's week-long celebration (my grandson's "favorite holiday of the year") to write at that time. (If it looks as if managed to keep up my blogging schedule, that's largely because I had a backlog of posts stored up for the purpose.)

Our missing persons list (always honored on the tablecloth participants sign every year) was longer than usual, but we still numbered over 30 people, and it was SO GOOD to get back to a reasonably normal life again. (If you don't count as abnormal spending most of a day trying to get a COVID-19 test when every source less than a two-hour drive away seemed to be out of stock.)

Holidays rarely retain much of their original purpose, so it's not surprising that Thanksgiving, too, has strayed far from its origins. But no amount of debunking and grinchiness will stop me from recognizing that this year marks the 400th anniversary of the First Thanksgiving. I know that that occasion was hardly unique in being a harvest festival celebration of thanksgiving to God. I know that many descendants of the original Native Americans at that feast wish that their ancestors had been a little less friendly with the Pilgrims. I know that the original looked far different from what is re-enacted in American elementary schools. I know that Thanksgiving didn't become a national holiday till Abraham Lincoln made it so.

So what? That doesn't change the fact that 400 years ago the Pilgrims, having suffered through a tremendously difficult year, gave a feast to return thanks to God for their survival, and shared that meal with their neighbors. We feast in memory of that festival, even if we don't always acknowledge it. And I want our grandchildren to know that if certain of that company had not been among those First Thanksgiving celebrants, they themselves would not be here today.

There were no decorated evergreens in Bethlehem. George Washington didn't refuse to lie to his father about a cherry tree incident. The first Easter had nothing to do with rabbits or eggs or candy. How many people really think about the birth of America on Independence Day, or about workers on Labor Day? Holidays take on a life and spirit of their own, and the alternative to enjoying them for what they are tends to be unhelpful grumbling. I will celebrate all that is good in our modern celebrations, and I will celebrate all that is good about what inspired them.

Happy 400th birthday, Thanksgiving!

What was happening at the beginning of the 1960's?

I've long been a fan of Randall Garrett's Lord Darcy books, so when I found the Kindle version of Randall Garrett: The Ultimate Collection for 99 cents, I leapt at the chance to read some of his other stories. Nothing so far has come close to the Lord Darcy books in quality, but they've mostly been fun to read.

Recently I read The Highest Treason. It's short, under 23,000 words, and was originally published in the January 1961 issue of the magazine Analog Science Fact and Fiction. You can find a public domain version at Project Gutenberg.

The Highest Treason deals with a subject familiar to me, one I first encountered in Kurt Vonnegut's Harrison Bergeron, first published in October 1961, in The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction. That one is much shorter, only 2200 words, and can be found here in pdf form.

C. S. Lewis's Screwtape Proposes a Toast was next—and my favorite. You can read it here, in the December 19, 1959 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. I don't have a word count, but it is also quite short.

December 1959, January 1961, October 1961. Three stories written as the 1950's passed into the 1960's.

All three have as their premise the consequences of a culture of mediocrity, in which excellence in anything—beauty, art, sport, thinking, work, character—is abolished for the sake of making everyone "equal." There must have been something going on at that time period to make it a concern for at least three such varied authors.

What would they think today? From the demise of ability grouping in elementary schools, to "participation trophies," to branding as racist and unacceptable the idea that employment and leadership positions should be awarded on the basis of merit and accomplishment, we have come a long way down this path since 1960.

Here's hoping it doesn't take near-annihilation by space aliens—or the flames of hell—to wake us up.

Permalink | Read 1148 times | Comments (1)

Category Reviews: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Education: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Politics: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Random Musings: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

Recently I re-read The Light in the Forest, a book from my childhood, though I hardly needed to read the whole book to find the passage I quote below. I could almost have quoted it from the memory of my first reading some sixty years ago.

These are the words of an old slave, in colonial America, explaining how easy it is for those born free to lose their liberty.

Every day they drop another fine strap around you. Little by little they buckle you up so you don't feel it too much at one time. Sooner or later they have you all hitched up, but you've got so used to it by that time you hardly know it.

My favorite Canadian lawyer has a weekly feature called "The Sidebar" in which he and American lawyer Robert Barnes spend an hour and a half to two hours interviewing very interesting people, most of whom I've never heard of. (No surprise there; I've never heard of most people.) I could enjoy these interviews very much, but that's a lot of time to give up so I usually resist. Recently, however, two caught my eye (ear?). It doesn't feel so bad if you can work on something else while listening.

The first interviewee was a large exception to my "never heard of him" rule: Scott Adams, of Dilbert fame. The second was unknown: Chase Hughes, behavior analyst, former military intelligence, interrogation expert, looks so friendly and innocent but is scary as all get out. I failed in my attempt to get any of his books from my usual free sources (library, Overdrive, Hoopla)—maybe they're considered too dangerous....

What links Adam and Hughes together is their interest in human behavior, persuasion, and hypnosis. They don't always agree; for example, while both are trained hypnotists, Adams insists that no one can be persuaded under hypnosis to do something against his own values, while Hughes says that's nonsense. For example, you can't directly make someone under hypnosis take off all his clothes in the middle of his workplace, but you can carefully lead him to believe he is about to step into the shower, and the logical consequences follow.

I don't have to like everything about these people and their ideas to find what they have to say both fascinating and frightening. I don't have to buy into their worldviews to acknowledge that what I believe to be free will choices are in fact far more vulnerable to influences we aren't even aware of than we can admit.

Perhaps more frightening than that is that both men agree that it is easy to make people remember as certainties things that did not happen. Implanting false memories doesn't even take a trained hypnotist, but can be done by a careless—or biased—questioner, especially if the subject is young, elderly, or otherwise particularly vulnerable.

Here are the interviews, for anyone who is interested and can find the time.

Permalink | Read 1154 times | Comments (0)

Category Random Musings: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

Every time I get close to abandoning Facebook altogether, I find something worthwhile I probably would never otherwise have seen.

"Utilitarianism is being carried out to its logical conclusions; in the interests of physical well-being the great principles of liberty are being thrown ruthlessly to the winds. The result is an unparalleled impoverishment of human life. Personality can only be developed in the realm of individual choice. And that realm, in the modern state, is being slowly but steadily contracted."-

—J. Gresham Machen, "Christianity and Liberalism", 1923

Permalink | Read 978 times | Comments (0)

Category Random Musings: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

Still waiting for baby news.

In the meantime, David Freiheit has the best analysis (9.5-minute video) I've seen yet of the tragic accidental shooting during the filming of Rust. For a guy who claims to know very little about guns, Freiheit nails the two most important points that even I (with still greater ignorance) know about gun safety:

- Always assume a gun is loaded until you have personally checked it out, and

- Never point a gun at anyone or anything you aren't willing to destroy, even if you are certain it's not loaded.

How one is supposed to handle shooting scenes with actors, I don't know, but I'm certain there are standard safety protocols. In any case, the "accidental" shooting of someone in a theatrical scene is a basic plot device in countless murder mysteries, and it's a bit of a shock to find life imitating art.

One interesting thing I learned from this video: criminal culpability must be proved "beyond a reasonable doubt," but determining civil culpability only requires "beyond a balance of the probabilities" ("fifty percent plus one"). Now you know.

Permalink | Read 959 times | Comments (0)

Category Random Musings: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

I'll admit it: I never like suffering. Especially suffering I believe to be unjust.

As a Christian, my greatest desire should be to be like Christ; however, there's a large part of me that would prefer to skip the suffering part.

Still, it happens. Not to the world-saving extent, but it happens, and I have to concede that good things often come from the pain. But in the midst of it all, it's awful, and that's when I like to return to one of my favorite passages from George MacDonald's The Princess and Curdie. (You can read the story free via Project Gutenberg. Or borrow it from your local public library, an important and underrated resource.)

The excerpt loses something out of context, since it misses both the reason for the pain and the good that came from it, but I find the image of the rose fire helpful when the pain feels overwhelming.

The room was so large that, looking back, he could scarcely see the end at which he entered; but the other was only a few yards from him—and there he saw another wonder: on a huge hearth a great fire was burning, and the fire was a huge heap of roses, and yet it was fire. The smell of the roses filled the air, and the heat of the flames of them glowed upon his face. He turned an inquiring look upon the lady, and saw that she was now seated in an ancient chair, the legs of which were crusted with gems, but the upper part like a nest of daisies and moss and green grass.

"Curdie," she said in answer to his eyes, "you have stood more than one trial already, and have stood them well: now I am going to put you to a harder. Do you think you are prepared for it?"

"How can I tell, ma'am," he returned, "seeing I do not know what it is, or what preparation it needs? Judge me yourself, ma'am."

"It needs only trust and obedience," answered the lady.

"I dare not say anything, ma'am. If you think me fit, command me."

"It will hurt you terribly, Curdie, but that will be all; no real hurt but much good will come to you from it."

Curdie made no answer but stood gazing with parted lips in the lady's face.

"Go and thrust both your hands into that fire," she said quickly, almost hurriedly.

Curdie dared not stop to think. It was much too terrible to think about. He rushed to the fire, and thrust both of his hands right into the middle of the heap of flaming roses, and his arms halfway up to the elbows. And it did hurt! But he did not draw them back. He held the pain as if it were a thing that would kill him if he let it go—as indeed it would have done. He was in terrible fear lest it should conquer him.

But when it had risen to the pitch that he thought he could bear it no longer, it began to fall again, and went on growing less and less until by contrast with its former severity it had become rather pleasant. At last it ceased altogether, and Curdie thought his hands must be burned to cinders if not ashes, for he did not feel them at all. The princess told him to take them out and look at them. He did so, and found that all that was gone of them was the rough, hard skin; they were white and smooth like the princess's.

"Come to me," she said. He obeyed and saw, to his surprise, that her face looked as if she had been weeping.

"Oh, Princess! What is the matter?" he cried. "Did I make a noise and vex you?"

"No, Curdie, she answered; "but it was very bad."

"Did you feel it too then?"

"Of course I did. But now it is over, and all is well."

Permalink | Read 980 times | Comments (0)

Category Random Musings: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

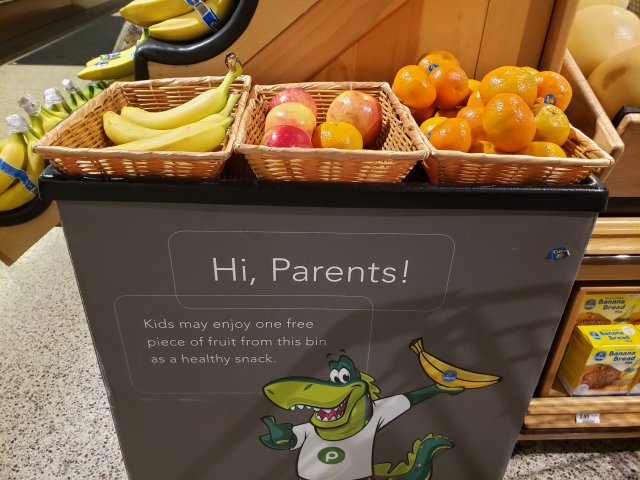

I was pleased to see the following display at our local Publix. It's certainly a healthier alternative to the cookies that are usually offered to children at grocery stores.

Then I thought a bit about it. It may be a healthier treat, but there's one thing missing: it's just a bin of fruit; there is no human interaction.

Years ago, when our kids went to the bakery to receive their much-anticipated free cookies, it was a social event. The interaction with the "cookie lady"—the smiles, the brief exchange of words, the opportunity to practice basic courtesies such as saying "thank you"—was a small but significant part of their social education. Reaching into a bin is impersonal.

Something is gained, but something is lost.

Many years ago our Swiss relatives marvelled at how much of American society is not automated. Switzerland automates where it can—in paying tolls and parking fees, for example—because labor costs are so high there. It is good to have work in Switzerland, because jobs pay well and workers are respected. But of course in consequence there are fewer jobs and they require higher levels of training.

Like it or not, the move toward automation is accelerating in America, spurred on by our response to the pandemic and the consequent labor shortage. This is not necessarily a bad thing, but there's no doubt that whenever we make a purchase online, choose a self-checkout line at the grocery store, take a course online instead of in person, listen to a sermon or watch a service online instead of attending a local church, or watch a movie at home instead of in a theater, we are giving up an opportunity for meaningful interaction with others.

I'm a cast-iron introvert, and my first reaction is, "So what?" The less personal option is usually more efficient, more convenient, and avoids the risk of having to deal with rude sales clerks and cranky classmates. Automation and online opportunities open up a huge world of information, possibilities, and choice.

The danger is that they can close off another world: the messy world of having to control our nastier impulses and deal with the personalities, cultures, viewpoints, and yes, nastier impulses of other people; the beautiful world of personal encounters that force us to see the humanity of those whom we might be tempted to hate if our encounter were in an online political forum instead of a line at Home Depot.

I am not one of those who likes to rail against the United States Postal Service. We have always had excellent, friendly service from our local post office, and almost all of our mail carriers have been people who care about their customers and serve above-and-beyond. Overall I think the system works well.

Further up the chain of command, however, I sometimes have my doubts. The following notice came from our bank this morning:

Effective October 1, 2021, the United States Postal Service (USPS) has revised its service standards for certain First-Class Mail items, resulting in a delivery window of up to five days. Please note that this may delay your receipt of mail from us and our receipt of mail from you (including mailed payments). Please take this change into account when mailing items to us via USPS.

Here's an explanation from the USPS website:

After carefully considering the Postal Regulatory Commission’s (PRC) July 20th advisory opinion, the Postal Service plans to move forward with adjusting service standards for First-Class Mail and Periodicals. The PRC concluded that the Postal Service’s proposed changes, in principle, are rational and accord with statutory requirements. The PRC made a number of recommendations for how the Postal Service should implement its changes, which the Postal Service is largely adopting. Additional details will be provided in an upcoming Federal Register notice. A majority of First-Class Mail and Periodicals will keep current service standards, with 70 percent of First-Class Mail volume having a delivery standard of 1-3 days.

The service standard changes are part of our balanced and comprehensive Delivering for America Strategic Plan, and will improve service reliability and predictability for customers and enhance the efficiency of the Postal Service network. The service standard changes that we have determined to implement are a necessary step towards achieving our goal of consistently meeting 95 percent service performance.

So, practically, mail service may seem the same for much of the time. But read that last line again: The service standard changes that we have determined to implement are a necessary step towards achieving our goal of consistently meeting 95 percent service performance.

I should not be surprised. Over several decades, I've seen it happen in our educational system, in business practices, in government services, and in social expectations. We talk a good game, but when it comes to actual accomplishment, time and time again I've seen organizations choose to meet their goals by bringing the goals down to their level of achievement, rather than the other way around.

Maybe the new standards are more realistic. Maybe there are a thousand excuses for not achieving what we set out to do. Certainly I've had to revise my personal goals too often. But if the purpose of the new goals isn't to help us move beyond them—further, better, higher—we can trap ourselves on a downward spiral of lowered expectations.

Permalink | Read 1194 times | Comments (0)

Category Random Musings: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

Every comedian knows what it's like to have a joke fall flat. It happens. But do they all receive lectures when their jokes fail?

I love our choir. We're casual, a bit wacky, and not all that good—it's a good fit for me—but we love each other and our work. We also cover a very wide spectrum when it comes to political, social, and even religious views, and one of the things that keeps us from being at each other's throats in these troubled times is humor.

You know what else I like about our choir? They laugh at my jokes. They tell me they like my sense of humor.

Maybe it's a choir thing. Maybe I've been in Florida too long. Maybe this is what happens to everyone as they get older. But it came as a shock to me that some people think I'm more demented than funny.

During our recent trip to the Northeast, I kept running into people who most definitely did not appreciate my sense of humor. Not only did they not laugh, but they reacted as if I were a particulary dense child with no understanding of the world. I'm not griping about specific people here; in fact, I don't remember who they were, nor what particular jokes fell flat. But the following examples are illustrative of the phenomenon.

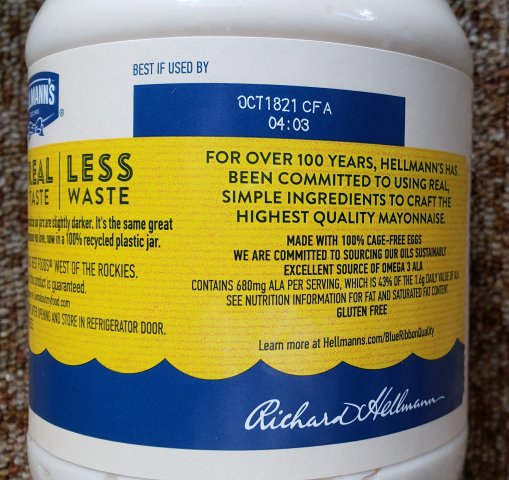

I came upon this jar of mayonnaise while sorting through our food supplies and checking expiration dates. I posted it to Facebook, with the caption, "What do you think? Is it time to rotate the stock in my pantry?"

And people laughed. They did not look blank and condescendingly explain to me that the date does not mean October 1821 but rather October 18, 2021.

As I was sitting in a doctor's office waiting area, I noticed that they had thoughtfully provided a small refrigerator, which sported the following sign:

Patient Water

Had there been anyone else in the room, I would probably have noted, "I guess the Impatient Water must be in another room." Due to my recent experiences, my mind filled in, "No, you don't understand. The sign means that the water in this refrigerator is for patients only."

My choir would have laughed. Maybe that's because they are a choir, in Florida, and with an average age that is, shall we say, elevated.

But it sure is good to be among people who think me clever rather than stupid!

Permalink | Read 1125 times | Comments (2)

Category Random Musings: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

Not a meme, but part of an actual conversation a couple of decades ago. The second speaker was Porter, the first one of his co-workers.

Permalink | Read 1087 times | Comments (0)

Category Random Musings: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Inspiration: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

Our doctor's office has yet another set of forms for us to fill out, and this one just has me wanting to throw up my hands and scream, "NONE OF YOUR BUSINESS!" Plus, some of the questions make no sense, in some cases giving far more options than reasonable, and in some cases too few.

For "Ethnic Background" I am given these options:

- Ashkenazi

- No

- Other

- Unknown

I understand that there are certain diseases that are more prevalent among Ashkenazi Jews, so maybe that's an important question. But there are also diseases that are especially prevalent among other populations, e.g. the Amish, and there's no opportunity to indicate that, other than the non-informative "Other." And just who are the No people—an obscure tribe of Papua New Guinea, perhaps? And is my own diverse ancestry, which took up some dozen slots on the 2020 census form, of no medical interest at all?

One ethnicity gets its very own question:

- Hispanic or Latino/a

- Not Hispanic or Latino/a

- Unknown or Not Given

I find that a curious question for a doctor to ask. Just how many diseases divide themselves by this criterion? If my lungs are congested, how much does it matter whether my ancestors came from Spain versus France? "Not Given" is beginning to look like the best answer for most of these questions.

There's a good deal more choice when it comes to Sexual Orientation:

- Bisexual

- Choose not to disclose

- Don't know

- Lesbian or Gay

- Something else

- Straight (not lesbian or gay)

- (You can hold the CTRL key while clicking to select multiple options)

Frankly, unless I'm indicating problems of a sexual nature, I don't think even my doctor needs to know this information, though she's welcome to guess based on the fact that I'll admit to being female and having a husband. "Something else" sounds attractively bear-poking, however.

But even Sexual Orientation has nothing on Religion!

- African Methodist Episcopal

- Agnostic

- Amish

- Anglican

- Assemblies of God

- Atheist/Humanist

- Baptist

- Buddhist

- Catholic

- Christian

- Christian Scientist

- Church of Christ

- Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints

- Decline to Answer

- Disciples of Christ

- Episcopalian

- Greek Orthodox

- Haitian Vodou

- Hindu

- Indian Orthodox

- Islam

- Jain

- Jehovah's Witness

- Jewish

- Lutheran

- Mennonite

- Messianic Judiasm [that's how they spelled it]

- Methodist

- Multi-Faith

- Nazarene

- Non-Denominational

- None

- Orthodox

- Other

- Pentecostal

- Presbyterian

- Protestant

- Quaker

- Rastafarian

- Russian Orthodox

- Scientologist

- Seventh Day Adventist

- Shinto

- Sikh

- Taoist

- Unitarian Universalist

- United Church of Christ

- Unknown

- Wiccan

- Zoroastrian

There are so many things wrong with this list I won't even try to ennumerate them, other than to mention that my Seventh-Day Baptist ancestors would be feeling left out. And to note that it's just plain weird to have so many choices yet list "Islam" as one-size-fits-all. For myself, being unable to choose among Anglican, Christian, Episcopalian, Multi-Faith, Non-Denominational, Protestant, and Other—and not having the ctrl/click option for this one—I might have to go with that fascinating new religion, Decline to Answer.

But really, of what possible importance could the answer to this question be for normal medical care, other than the above-mentioned correlation between being Amish and certain diseases? Even that is an ethnic difference, not a religious one. Do Wiccans require different cancer treatments from Zoroastrians? True, Jehovah's Witnesses don't want blood transfusions, so that's important to know, but I think it would be safer and more efficient to ask that question directly, rather than make the assumption. I suspect not all JW's reject them totally, and for all I know, some other religion frowns on them as well.

Maybe these questions are required by Medicare. I have had more patience with my medical caregivers (though less with the government) ever since I learned that the very annoying questions they started asking at every visit were government-imposed: Have you fallen at all in the last year? "I have grandchildren. Falls are the natural consequence of fun." Have you been depressed during the last year? "I'm here for a physical, not a mental."

It's a good thing we like our doctors. The bureaucracy is rapidly eroding my confidence in the system.

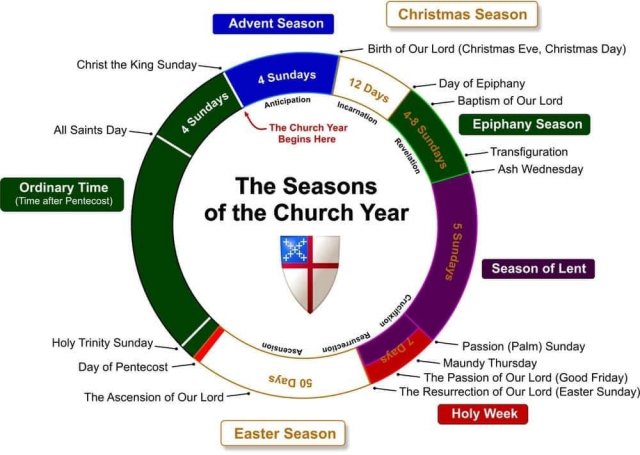

I'm giving my computer files a much-needed spring summer cleaning, and came upon this, which I post here for my own future reference as much as anything. Unfortunately, I don't remember where it came from. The odds are it was from someone on Facebook, but that's the best I can do for now.

It's a clear, concise, visual guide to the seasons of the Church Year, as celebrated in the Episcopal Church and many other churches. The latter may differ in small details; I'm not familiar enough with them to say. But when I refer to the Church Year, this is what I'm talking about.