I have too many Kindle books.

Granted, 280+ is a drop in the bucket compared with the physical books that crowd our bookshelves. Many of the ebooks are duplicates of physical books I already have, books I value so much I want them in both forms so I can easily search and highlight. But many are unique, since I find it very hard to resist when eReaderIQ alerts me that a book I'm interested in is on sale for $2.99 in Kindle form. While I really love the feel (and often smell) of physical books, I also appreciate what ebooks have to offer.

What concerns me, when I say I have too many Kindle books, is that I've bought and paid for them, but they're not really mine. Amazon has the ability—and sadly the right—to reach down into my Kindle and take them away from me at any time. True, they're supposed to refund the purchase price if they do so, but that's absolutely not the point. This was a concern I had at the very beginning of my relationship with Kindle, when I read the Terms & Conditions. I conveniently shelved the worry as the years went by with no problems. However, in these days of repeated attacks on First Amentment freedom of speech, social media posts and whole accounts being deleted for no reason other than that the platform objects to the (legal, protected) content, and people living in fear of offending algorithms—well, you can imagine why paranoia has returned.

I'm not certain what to do about it, other than what I just did: order a physical book that I don't actually want, just because I can imagine its very important content offending the Powers That Be enough for Amazon to make it disappear. I guess I can call it a donation to the author.

Maybe I should reread Fahrenheit 451. While I still can.

I love Better World Books, and tend to spend a fair amount of money on their site. Why? Because they are without a doubt the least expensive way to ship books to our overseas grandchildren. I also appreciate that their prices are usually pretty good, if you're okay with used books. It's true they are a bit disingenuous with their "free shipping" policy, since the price of the same book rises considerably if you ship it overseas instead of within the U.S. I'm okay with that, but I don't call it free shipping when the cost is bundled into the price of the book. However, that cost is still a lot less than if I shipped the books myself, so I'm not complaining.

(Well, not about Better World Books, that is. I will complain about the United States Postal Service for its totally unreasonable charges for shipping overseas. They have skyrocketed in recent years, and the only thing that makes me stay with them is that other shipping agents are worse. It's why we never can pack light when we go to Switzerland, as it only makes sense to pack rather than ship.)

It also feels good that for every book I buy, Better World Books donates a book to one of the literacy and library charities that they support, and that's just one of the ways they promote reading. I'm sure they've done a lot of good.

But I'm quite glad that their corporate philanthropy is not the reason I buy from Better World Books. Otherwise I wouldn't know what to do with the discovery I just made.

You see, one of their major partners is a charity called Books for Africa. I learned that on this page. Here's an excerpt:

Better World Books donated 22,000 books to Books For Africa. This sea container went to Bangui and the Central African Republic. These books were part of a shipment of textbooks, part of an ambitious effort called “Million Books for Gambia (MB4G) Project.

“Thank you for your recent contribution to Books for Africa! Your donation towards sponsoring a container to the Central African Republic helps put books into the hands of African children who are eager to learn. We have well over one million books in our warehouse facilities just waiting for funds to ship them to Africa! Books for Africa remains the world’s largest shipper of donated text and library books to the African continent, shipping over 40 million books to 53 countries since since 1988. ” — Patrick Plonski, Executive Director, Books for Africa

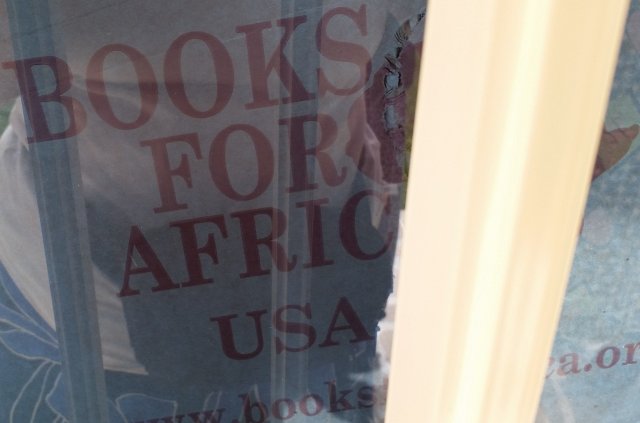

I can ignore the fact that they have apparently conflated (or confused) the Gambia and the Central African Republic. What disturbs me is this photo from our visit to the University of the Gambia in 2016. It's taken through glass, looking into a storage closet, so it's not clear that there were boxes and boxes from Books for Africa piled in there, unopened. We were informed that they had been sitting there, untouched, for many months.

Will they ever do anyone any good? Are they still sitting there, in that closet? Are they sitting there because the university is falling down on the job, or because they know the books are likely to be useless First World castoffs? That happens more than we like to think. When Porter worked in Bangladesh, he noted that "charitable gifts" from Scandinavia often included winter coats and hats. For Bangladesh.

Could the money and effort that went into gathering these books and getting them to the Gambia's only university have been better spent? This is only one of the questions raised by our visit to the Gambia. Charitable giving is a much more complicated and nuanced affair than we want to believe.

Fortunately, in the case of Better World Books, that's not my problem. They can continue to work as they see fit to make the world better; undoubtedly there will be some hits among the misses. And I'll continue to thank them for making it possible—even reasonable—to send books to our family overseas.

Permalink | Read 960 times | Comments (3)

Category Random Musings: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Conservationist Living: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

Not many of my readers are familiar with the writings known as the Apocrypha. I find it a shame it took me so long to discover something so important in classical literature and art, but better late than never. Anyway, parts of it are fascinating, other parts less so. For me, wading through the books of the Maccabees is somewhat of a slog, as I'm not fond of endless recountings of wars and battles—not here, not in the Old Testament, not in the Iliad—but that's just me. True, it's interesting to read about the historical period between the Old and New Testaments; nonetheless I find the stories of Tobit, Judith, and Susannah more enjoyable.

There are some gems hidden amongst the tales of fighting, and here is one of them, found in the first chapter of Second Maccabees:

When our fathers were being led captive to Persia, the pious priests of that time took some of the fire of the altar and secretly hid it in the hollow of a dry cistern, where they took such precautions that the place was unknown to any one. But after many years had passed, when it pleased God, Nehemiah, having been commissioned by the king of Persia, sent the descendants of the priests who had hidden the fire to get it. And when they reported to us that they had not found fire but thick liquid, he ordered them to dip it out and bring it. And when the materials for the sacrifices were presented, Nehemiah ordered the priests to sprinkle the liquid on the wood and what was laid upon it. When this was done and some time had passed and the sun, which had been clouded over, shone out, a great fire blazed up, so that all marveled. ... Nehemiah and his associates called this “nephthar,” which means purification, but by most people it is called naphtha.

Permalink | Read 1005 times | Comments (0)

Category Random Musings: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

When my economist husband tells me an modern article is both consistent with everything he learned about economics in college and in life, and has also taught him something new, I take notice. The article in question is Inflation Reaches Unicorns, by John Mauldin, and should be accessible at that link.

It truly is about economics: investments, venture capitalists, inflation, and yes, even unicorns ("large, well-known companies [which] are choosing to stay private long past the point where they would once have gone public"). It's a cogent and interesting analysis of how we got where we are and where we might be going.

However, what really made me perk up was some excerpts from a forthcoming book by Edward Chancellor, entitled, The Price of Time: The Real Story of Interest. Here Chancellor is actually quoting "Bastiat"—probably French economist Frédéric Bastiat—and it's not clear to me where one ends and the other begins. It's the thought that counts.

In the sphere of economics, a habit, an institution, or a law engenders not just one effect but a series of effects. Of these effects only the first is immediate; it is revealed simultaneously with its cause; it is seen. The others merely occur successively; they are not seen; we are lucky if we foresee them. The entire difference between a bad and a good Economist is apparent here. A bad one relies on the visible effect, while the good one takes account of both the effect one can see and of those one must foresee.

The bad economist, says Bastiat, pursues a small current benefit that is followed by a large disadvantage in the future, while the good economist pursues a large benefit in the future at the risk of suffering a small disadvantage in the near term. The American journalist Henry Hazlitt elaborated ... in his bestselling book Economics in One Lesson (1946). Like Bastiat, Hazlitt lamented the "… persistent tendency of men to see only the immediate effects of any given policy, or its effects on only a special group, and to neglect to inquire what the long-run effects of that policy will be not only on the special group but on all groups. It is the fallacy of overlooking secondary consequences."

As I read this, what struck me was its applicability to much more than economics. In particular, read the above paragraphs with an eye to the response of our leaders to the COVID-19 crisis, and you'll see a stunningly accurate description of "bad economics." A more obvious example can hardly be imagined of considering only the immediate effects of a policy, and its potential effects on only a special group, while not only neglecting, but actively suppressing, any thoughts about what might be the long-run effects of that policy on the community as a whole.

[This post was originally entitled, "Camouflage"; I've now changed that to make it part of my "YouTube Channel Discoveries" series.]

Here's another YouTube channel we've been enjoying: Chris Cappy's Task and Purpose. How on earth could I enjoy videos about military tactics, strategy, history, and weapons? Here's a quote from the channel's About section:

Chris Cappy the host is a former us army infantryman and Iraq Veteran. This YouTube channel is a forum for all things military. From historical information to the latest news on weapons programs. We discuss all these details from the veteran's perspective. The first priority with our videos is to be entertaining.

I guess it's the last sentence. Chris Cappy is knowledgeable and entertaining. He may bill himself as "your average infantryman," but he's not your average military college professor droning on in the front of an auditorium filled with bored students.

The video that hooked me is the one below, How Camouflage Evolved (15 minutes). I'm certain we have grandchildren who would find it as enjoyable as I did.

Permalink | Read 2155 times | Comments (0)

Category Reviews: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Education: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Random Musings: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Just for Fun: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] YouTube Channel Discoveries: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

I have lived under three different American flags.

Flag Day, 2022

Permalink | Read 1122 times | Comments (0)

Category Random Musings: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

Back in April, we ran into an opinion piece by Gary Smith entitled, "Believe in Science? Bad Big-Data Studies May Shake Your Faith." (Yes, I do save up articles in my Blog Idea Bank. Sometimes they're too out of date by the time I get around to them, but often they are still relevant.) The link is to the original article at Bloomberg, but if you've run into your free three article limit, you should be able to find it in many other places, including the New York Times and our own Orlando Sentinel.

Smith's thesis is that the current availability of so much data that can be mined, refined, poked, prodded, and manipulated is making for bad science. There's some good science, too, but a lot that is simply nonsense—and we don't know which is which.

The short article is worth reading in its entirety, but here are some quotes to pique your interest.

The cornerstone of the scientific revolution is the insistence that claims be tested with data, ideally in a randomized controlled trial. ... Today, the problem is not the scarcity of data, but the opposite. We have too much data, and it is undermining the credibility of science.

Luck is inherent in random trials. ... Researchers consequently calculate the probability (the p-value) that the outcomes might happen by chance. A low p-value indicates that the results cannot easily be attributed to the luck of the draw. [This number was arbitrarily decided in the 1920's to be 5%.] ... The “statistically significant” certification needed for publication, funding and fame ... is not a difficult hurdle. Suppose that a hapless researcher calculates the correlations among hundreds of variables, blissfully unaware that the data are all, in fact, random numbers. On average, one out of 20 correlations will be statistically significant, even though every correlation is nothing more than coincidence.

All too often, [researchers] correlate what are essentially randomly chosen variables. This haphazard search for statistical significance even has a name: data mining. As with random numbers, the correlation between randomly chosen, unrelated variables has a 5% chance of being fortuitously statistically significant. Data mining can be augmented by manipulating, pruning and otherwise torturing the data to get low p-values. To find statistical significance, one need merely look sufficiently hard. Thus, the 5% hurdle has had the perverse effect of encouraging researchers to do more tests and report more meaningless results.

A team led by John Ioannidis looked at attempts to replicate 34 highly respected medical studies and found that only 20 were confirmed. The Reproducibility Project attempted to replicate 97 studies published in leading psychology journals and confirmed only 35. The Experimental Economics Replication Project attempted to replicate 18 experimental studies reported in leading economics journals and confirmed only 11.

It is tempting to believe that more data means more knowledge. However, the explosion in the number of things that are measured and recorded has magnified beyond belief the number of coincidental patterns and bogus statistical relationships waiting to deceive us.

Permalink | Read 1018 times | Comments (2)

Category Random Musings: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

You heard it here first.

President Vladimir Putin of Russia has always seemed dangerous, and somewhat demented, to Western eyes, and his invasion of the Ukraine seems to bear out that impression.

Commentators delight in explaining how deluded the Russians were at every level, expecting to find Nazis on every corner and a hero's welcome from the Ukrainian people. How is it that they had only pre-Chernobyl disaster maps and thus had no idea what they were walking into when they dug into highly radioactive soil? Why do the soldiers and officers so often act like poorly trained recruits? And why is their military equipment so old, sometimes almost half a century out of date?

Everyone knows by now that COVID isolation has driven mental health crises through the roof, and anyone who watched the Olympics knows that Putin has taken those recommendations to the extreme. Is it possible that the president of Russia has simply been driven batshit crazy?

Maybe. Probably.

On the other hand, there could be another explanation.

Suppose you're the president of a country with expansionist ambitions and a burning envy of Western military technology. What do you do?

- You could pour a lot of money into developing and building modern equipment for your own military

- You could ramp up your espionage network and steal the technology and then build your equipment

- You could buy captured American military equipment from the Taliban

Maybe your economy won't stand up to a large increase in military spending. Maybe you don't have the resources to build what you need. Maybe you resent the time it would take to do the job well. So what do you do?

Maybe, just maybe, you invade a nearby, relatively defenseless country. And you do it very poorly. Like the Duchy of Grand Fenwick,* you aren't hoping to win. At least not yet.

You send in your greenest troops and your vehicles and guns otherwise destined for the scrap heap. You lose no opportunity to tweak the rest of the world with your arrogance, your obvious incompetence, and your crimes against civilians, thereby raising the hackles of countries with the greatest array of the most advanced military technology in the world. You allow the war to drag on and on, giving these countries plenty of time to pour billions and billions of dollars worth of advanced technology and powerful equipment into the land you have invaded but not yet captured.

And then?

Then you bring out your A team, your first string, your best and most experienced soldiers, along with the most modern equipment you can muster, all of which have been held back just for this moment. In one fell swoop, you crush the opposition and capture all that lovely best-in-the-world military might.

You lost some inferior soldiers and a bunch of scrap-metal tanks. So what?

Well, okay, you didn't count on the damage a massive embargo would do to your economy. In the end it might have been cheaper to do the work yourselves.

Then again, with all that captured equipment and intellectual capital, the next invasion is going to go a lot more smoothly....

*No relation to Fenwick, Connecticut, as far as I know

Permalink | Read 1027 times | Comments (1)

Category Hurricanes and Such: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Random Musings: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

We're suffering from an epidemic of corporate philanthropy.

Businesses, especially large corporations, are bragging loud and long about their so-called good deeds, whether political or environmental or social or anything else trending in pop culture.

I am not impressed.

If you are a local business (even if that business is a franchise of something larger), and you host fundraisers for your local high school crew team or church youth group, or if you offer goods and services to first responders and disaster victims in your community, go for it. I'm likely to think better of you. That's neighborliness.

But anything on a grander scale than that, no. When you donate funds to support political parties, or activist organizations, or the arts, or even the most benign of charities, whose money are you really spending? Unless you have no shareholders, no employees, no board of directors, and no customers, there's a case to be made that you are making them all unwitting—and in many cases unwilling—donors to your own favorite causes.

Here's what I suggest.

Do you have some extra profit you want to do good with? Consider any or all of the following:

- Give all your employees an across-the-board raise. Or a one-time bonus, if you're afraid the profits won't be sustainable.

- Increase the dividends you pay your stockholders.

- Decrease your prices.

In this way you would help your workers/investors/customers—those who make your profit possible—in a tangible way, while at the same time increasing their ability to support the causes they believe in, instead of the pet causes of a small group of elite corporate decision-makers.

It's your choice. If you want to use company profits to support a particular presidential candidate, or to buy the CEO a new yacht, that's your business. Just don't expect the world to believe that your actions are virtuous.

Is there anything more hypocritical than being generous with other people's money?

The first step in taking control of a nation is the simplest. You find someone to hate. ... You will find that hate can unify people more quickly and more fervently than devotion ever could. — Brandon Sanderson (Elantris)

Hatred is not an emotion that is foreign to us. Its presence in the world does not surprise me. What I find shocking is how easy we are manipulated into hating.

No one has to convince me to root for the Ukraine in the current conflict with Russia. After all, I'm a child of the Cold War, when the Soviet Union was always our number one enemy. In this case, they are obviously the invaders, perpetrating atrocities, and even threatening nuclear war. We remember Georgia, Crimea, Belarus, and ask, "Where will it stop if it doesn't stop here?"

But two thoughts give me pause.

First, the level of anger and hatred I see, directed against anything Russian (even harmless Ukrainians with Russian-themed businesses in the U.S.), exceeds reason—as I have seen increasingly on other issues in recent years. We are in grave danger of losing sight of the essential humanity of the Russian people, much as the people of Germany once lost sight of the essential humanity of their friends and neighbors.

Second, while the flame of anger arose naturally in our hearts, it has been and is still being unnaturally accelerated into this disastrous conflagration. Politicians, corporations, educational institutions, news organizations, social media, celebrities of all sorts, our own friends—the push is on to view the Ukraine as totally innocent victims and Russia as completely irrational, evil villains. Merely to suggest that Russia might have had legitimate fears and concerns that led to the move to "liberate" the Ukraine, or that the Ukraine might not be completely free of corruption and illegitimate actions, is to bring down the wrath of all who want to see (or who want us to see) this as a battle between absolutely good and absolute evil.

Even if that were true—and nothing in this world has that kind of clarity—it's bad policy. Unless you really want World War III.

But here's what's really concerning me: I am convinced that if "they"—used metaphorically, not specifically—wanted the completely opposite reaction, they could just as easily have engineered that instead. You don't need to posit a conspiracy behind the power of this behemoth conglomeration of government, media, academia, financial institutions, entertainment, big businesses, Big Tech, and ordinary peer pressure. Ideas themselves have power, and when all these very powerful entities align to push an idea, it becomes almost irresistible.

The beginning of resistance is to step back and ask, "Where did I get this idea? What is driving my response?"

It's "Museums on Us" weekend, and time to take a look at what might be new around town. Usually that means the Orlando Museum of Art and the Mennello Museum of American Art. Sometimes they have lovely exhibits, and we might go back to take another look at some of what we saw last October.

But the museum websites and the descriptions of new exhibits are not inspiring this month. Here, from the Mennello's site, are a couple of paragraphs that could not possibly have been designed to draw us in.

Many of the artists presented here approach their creative practices conceptually and methodologically, as a means of researching, solving, expressing, and effectively visualizing increasingly complex theories and stylistic ideas across time and disciplines. They have drawn upon personal experience, art history, advances in science, and popular culture to create works that unify formal art theory with current understandings in fields including anthropology, biology, math, philosophy, physics, and psychology. Broadly, the themes explored by the artists fall into reobserving and reimagining of traditional subject matter and the emotional content imbued in still lifes, landscape, and the figure.

“The work ... presented in this exhibition challenges perceptions of language, identity, preservation, and adaptation in both real and hypothetical worlds,” said Katherine Page, curator of art and education, Mennello Museum. “I am especially interested in artistic production, as its contextualizing framework runs parallel to the scientific method that combines the decades-long history of science, printmaking, and modern and postmodern art developments. The artists here are researchers, observers, experimenters, and publishers. As publishers, they share their exciting results—renderings of creation, communication, and conceptualization with a public beyond traditional, specialized academic fields.”

Huh?

I'm not picking on the Mennello in particular. This kind of verbiage abounds in art museums all over. I'm accustomed to dealing with technical language in other fields, and I grant that maybe this makes sense in the higher echelons of the art world, but to the hoi polloi like me it's more than incomprehensible: it sounds utterly irrational. Why would I want to spend time with art that "challenges perceptions of language, identity, preservation, and adaptation in both real and hypothetical worlds"? When I go to an art museum, I'm seeking the good, the true, and the beautiful. Ordinary life is enough of a challenge for me.

When I am working on a problem, I never think about beauty but when I have finished, if the solution is not beautiful, I know it is wrong. — Buckminster Fuller

Permalink | Read 1379 times | Comments (0)

Category Random Musings: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

The science fiction writers of the 20th century were often startlingly accurate in their technological predictions, as when Arthur C. Clarke suggested, in 1945, the use of satellites in geostationary orbit to facilitate worldwide communication. They also frequently missed the mark: we hold more computing power in our hands than those writers could imagine, yet we still don't have personal jet packs, let alone interstellar travel.

Science fiction often made social predictions as well, and they too sometimes hit the mark. Here, for example, is a quote from Randall Garrett's Anything You Can Do (published in 1963).

The number of people killed in ordinary accidents in a single week was greater than the total number killed by the Nipe in the last decade, but nowhere were men banding together to put a stop to that sort of death. Accidental death was a known factor, almost a friend; the Nipe was stark horror.

Replace "the Nipe" with "COVID-19" or "guns" and you get the same attitude.

The next is from The Highest Treason (1961). In the 60 years that have passed since it was written, I have seen this prediction come true with a vengeance for much of the Western world.

Marriage was a social contract that could be made or broken at the whim of the individual. It served no purpose because it meant nothing, neither party gained anything by the contract that they couldn't have had without it. But a wedding was an excuse for a gala party at which the couple were the center of attention. So the contract was entered into lightly for the sake of a gay time for a while, then broken again so that the game could be played with someone else.

More from The Highest Treason. If we haven't yet managed economic levelling, it's not for want of people pushing for just that. We've already made long strides in the battle against high standards and excellence, particularly in education.

Earth was stagnating. Every standard had become meaningless because no standard was held to be better than any other standard. There was no beauty because beauty was superior to ugliness and we couldn't allow superiority or inferiority.

Society had decided that intolerance and hatred were caused by inequality. Raise the standard of living. Make sure that every human being has the necessities of life—food, clothing, shelter, proper medical care, and proper education. More, give them the luxuries, too.... There was no longer any middle class simply because there were no other classes for it to be in the middle of.

But the poor in mind and the poor in spirit were still there—in ever-increasing numbers. Material wealth could be evenly distributed, but it could not remain that way unless Society made sure that the man who was more clever than the rest could not increase his wealth at the expense of his less fortunate brethren. Make it a social stigma to show more ability than the average. Be kind to your fellow man; don't show him up as a stupid clod, no matter how cloddish he may be.

All men are created equal, and let's make sure they stay that way!

Well, that's depressing. It's a good thing that as a child the social commentary in my beloved science fiction stories went over my head, probably because I had no interest in it. Or maybe this is the sort of thing that only becomes obvious when we can look back over the years.

Permalink | Read 1157 times | Comments (0)

Category Random Musings: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

Chick-fil-A posted this sign:

Today, we remember a

great leader, humanitarian

and Atlantan, while pausing

to reflect on his legacy

When you're retired, most Federal holidays boil down to "days on which we don't get any mail." But yes, I do know what today is. Nonetheless, I puzzled over this longer than I should have. Atlantan? What mythological association links Martin Luther King, Jr. with the Lost City?

It didn't take too many seconds for the penny to drop, but this may be an indication that my recent reading has been heavily weighted towards the Fantasy genre.

Permalink | Read 1038 times | Comments (0)

Category Random Musings: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

December in Florida can be interesting, weather-wise. One day we wear sweatshirts, the next shorts. Not long ago I noted that I had used the electric heater in my office and a couple of hours later turned on the air conditioning in my car. It's not unusual—and it's also not new.

It's tempting to look at our currently warm temperatures and think it a recent phenomenon. Today's high is predicted to be 84 degrees. Must be due to climate change, right?

It could be. I'm not denying that the climate changes, and we've personally seen the dramatic effects of warming on Alpine glaciers over the last 50 years. But not everything that looks like a hammer, really is a hammer. I was recently browsing through my journal from 1984—the year we moved to Florida, more than a quarter century ago—and found this entry for Friday, December 21.

Hello winter! By the calendar, of course. It's still hot here—highs in the 80's.

So, December 1984 was about the same as December 2021. I'm kind of hoping January doesn't follow the same pattern, though. This is from the entry one month later, January 21, 1985.

Brrr! Hard freeze last night. It was 23 degrees when we got up.

Experiences like this make me wish my journal hadn't eventually fallen victim to other priorities of life. I've lived long enough that it provides cultural as well as personal perspective. For the same reason I enjoy reading the journals my father kept, though he, too, left frustratingly blank years.

Speaking of years, 2022 is nearly upon us. We are finding it difficult to feel the passage of time correctly. The years 2020 and 2021 have upended our our lives, and time is out of joint. Be that as it may, we wish you all a

Happy New Year!

Permalink | Read 1089 times | Comments (0)

Category Random Musings: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

Those who are smart and protecting themselves need to continue doing their best to protect themselves and their loved ones.

I found this in a comment on a friend's Facebook post. One advantage of information overload is that such comments quickly become "anonymized information" in my brain, protecting the innocent and the guilty alike.

What struck me about this statement, with which I heartily agree, is what it tells me about how much we are alike. We all want to protect ourselves and our loved ones, and most of us have opinions as to how best to do that.

It is in the means, not the ends, that we disagree.

Some people move to rural areas and learn to farm. Some organize and join unions. Some purchase and learn to use guns. Others choose to homeschool, or to take political action, or to stockpile food and other essentials. Some work hard to strengthen family and community ties, or to attend to their own physical fitness, or to build up a strong financial base. And some people get vaccinated against COVID-19. Many choose more than one of these paths.

The writer of the Facebook comment was specifically speaking of COVID-19 vaccination, which I certainly consider to be a valid way of choosing to protect oneself and one's family. Unfortunately, the context of the above quotation wasn't as reasonable.

I know this is callous, but those who are smart and protecting themselves need to continue doing their best to protect themselves and their loved ones. What happens to those who do not care, is no longer taking up my headspace.

Just as the excerpt epitomizes what we have in common, the context shows what is dividing us. Because by "those who do not care," the writer appears to mean those who choose not to follow his own particular choices. Possibly, he's expressing his willingness to leave them alone to make their own decisions. But the callousness, which he admits, contains the implication that he considers doing them harm to be a valid part of protecting himself.

That is very dangerous ground indeed. We can do better.

Permalink | Read 1048 times | Comments (0)

Category Hurricanes and Such: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Health: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Politics: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Random Musings: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]