Not long ago, I ran down an interesting rabbit hole.

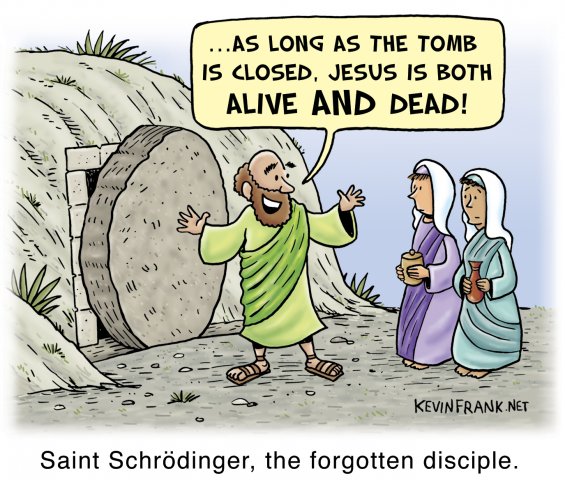

As a genealogy researcher, i have both an interest in and a knack for finding people and stories. Today a friend's casual comment on a completely unrelated subject led me eventually this meme on Facebook:

It caught my eye, both because it speaks an important truth and even more because I knew a friend who would especially appreciate it. But I'm also researcher enough not to pass something like this along without knowing more about the context. So I did a Google image search for the picture.

That turned out to be so much easier than most of the image searches I do. I've mentioned before that I'm organizing my father's journals, and also the old photographs from the same time period. Since most of the labelling on the photos is missing or minimal, Google Lens has been of immeasurable assistance, though a good deal of detective work is still necessary.

The context of this photo popped up immediately. (Well, almost—I'll get to that caveat in a moment.) Wikipedia has the exact picture, and helpfully explains that it is a photo of "Polish Jews being loaded into trains at Umschlagplatz of the Warsaw Ghetto, 1942." On this, I think Wikipedia can be trusted. So it's legit.

But I mentioned that the search wasn't exactly as easy as I had implied. That's where this rabbit hole got especially interesting.

Google refused, at first, to show me any results, as they were likely to be "explicit." I don't know about you, but to me, that designation implies that the results would show me pornography or graphic violence or other obscenity. Granted, the ideas and actions represented by that photo are obscene enough, but not the photo itself, which legitimately documents an important and dangerous time period.

In order to see it, I had to turn off Chrome's "Safe Search" feature, which I had heretofore assumed was there to filter out graphic sex and violence. The feature manages to discern the difference between pornography and the naked ladies featured in art museums; why is historical data a problem? Some day I may get curious enough to check out other browsers. Anyone here have experiences to share?

On top of that, I learned that what I was seeing was someone's second attempt at sharing this meme, Facebook having taken down the first. What Facebook found offensive I do not know. I'm tempted to post it directly myself and see what they do, but I'll try cross-posting this first. I generally just post links to Lift Up Your Hearts! when I want to share them on Facebook, and I doubt the FB censors will dig that deep. We'll see.

Here's why it matters: Knowledge of history is essential. My 15-year-old self would have choked on that, as of all the history classes I endured, there was only one I thought worthwhile. (I take that back; there was also the unit on Native Americans back in fourth grade, which was pretty cool.) Nonetheless, one of the lessons I remember best from all my years in school is that one of the clearest characteristics of a totalitarian régime is its attempts to cut its people off from their own history, whether by re-writing it (à la the novel 1984) or by changing the language (whatever the benefits of simplified Chinese, it has greatly limited the people's ability to read historical Chinese documents), or by simply encouraging an atmosphere of ignorance.

The meme, it turns out, is as much about the First Amendment as the Second.

I'm putting this in the "Just for Fun" category, because laughing at small annoyances is like removing the stone from your shoe before it has a chance to raise a blister.

This just in from Porter's Spectrum news feed, emphasis mine:

With interest rates in the 7% range, home buyers, and even sellers, are seeing a change in the housing market.

I told you weird things are happening these days. Why, next thing you know, we'll be hearing about hikers whose health apps indicate that they change elevation both going up and going down a hill! Or that despite the best efforts of government, academia, Hollywood, and Big Tech, Newton's Third Law is still in effect.

(I tried to work Pharma and Factory Farming into the list, but it seemed like overkill. Oops—I mean it seemed a bit too much. Despite the banned four-letter word "k--l" embedded in the term, that was not a call for violence.)

Permalink | Read 1035 times | Comments (1)

Category Just for Fun: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

Eight Flavors: The Untold Story of American Cuisine by Sarah Lohman (Simon & Schuster, 2016)

Eight Flavors: The Untold Story of American Cuisine by Sarah Lohman (Simon & Schuster, 2016)

This was not the Sarah Lohman book that first caught my eye. That honor belongs to Endangered Eating: America's Vanishing Foods, which was published in October of last year. But I make extensive use of eReaderIQ to find good prices for Kindle books, and Eight Flavors came up first.

Lohman tells the stories of eight quintessentially American flavors: where they came from, how they get to us, how they became "American" from their widely divergent sources. This is a book my father would have loved, and so, I believe would my sister-in-law, who has in the past given us several similar books.

Eight Flavors is easy and delightful reading. My main complaint is that Lohman is thoroughly immersed in her modern, urban culture, in which heretofore objectionable language is casually used, and worse, historical events cannot be presented without pointing out how oppressive and racist the people were back then. A simple example: In the chapter on garlic, she quotes a 1939 magazine article that remarks on the cultural assimilation of Italian-American baseball superstar Joe DiMaggio with, “He never reeks of garlic and prefers chicken chow mein to spaghetti.” Lohman dubs it "first-class casual racism," even though her chapter clearly explains that garlic, a hallmark of Italian cooking, was still a foreign taste to many Americans. I remember that when we lived just outside of Boston, the train would pass a set of apartments that were popular among people from India; the scent of Indian spices was distinctive and pervasive, even from the train. I'll grant that there's no subtlety in that observation—for all I could tell, the residents might have been Bengali or Pakistani rather than Indian—but there's nothing evil about it. Noting that one can often tell by sense of smell what food a person has recently eaten is not racist—especially when the flavor is as strong as garlic.

She also reveals her (sometimes understandable) contempt for people who don't recognize that "chemical additives" are sometimes identical to the chemicals present in totally natural products. She acknowledges that the flavors found in nature are much more complex than the primary flavor molecule (e.g. vanilla versus vanillin) but at the same time dismisses the point.

All that aside, it's an enjoyable book. I'll share Lohman's list of delightful flavors to whet your appetite.

- black pepper

- vanilla

- chili powder

- curry powder

- soy sauce

- garlic

- monosodium glutamate (MSG)

- sriracha

One of my favorite books is Peter Drucker's Adventures of a Bystander. In "The Monster and the Lamb," one of the many page-turning essays about the people and events that shaped his life, Drucker reveals the actions he took in 1933 to assure that he could not back out of his determination to leave his promising and comfortable life in Germany, should Hitler come to power.

I also made up my mind to make sure that I could not waver and stay. ... I began to write a book that would make it impossible for the Nazis to have anything to do with me, and equally impossible for me to have anything to do with them. It was a short book, hardly more than a pamphlet. Its subject was Germany's only Conservative political philosopher, Friedrich Julius Stahl—a prominent Prussian politician and Conservative parliamentarian of the period before Bismarck, the philosopher of freedom under the law, and the leader of the philosophical reaction against Hegel as well as Hegel's successor as professor of philosophy at Berlin. And Stahl had been a Jew! A monograph on Stahl, which in the name of conservatism and patriotism put him forth as the exemplar and preceptor for the turbulence of the 1930s, represented a frontal attack on Nazism. It took me only a few weeks to write the monograph. I sent it off to Germany's best-known publisher in political science and political history.... The book, I am happy to say, was understood by the Nazis exactly as I had intended; it was immediately banned and publicly burned. Of course it had no inmpact. I did not expect any. But it made it crystal-clear where I stood; and I knew I had to make sure for my own sake that I would be counted, even if no one else cared.

That passage has been on my mind lately. I have a strong feeling that I need to follow his example, albeit in my own, minor way. Whether big actions or small, doing the right thing is still doing the right thing. I don't have a well-known publisher ready to print whatever I might send them, but I have the internet, and a blog platform that is not subject to the censors of YouTube, Facebook, or any other Big Tech platform.

I have a duty to stand for the truth. For Truth.

Not my truth, but the truth as I see it. The former implies that there are many personal truths, but no real, independent, objective Truth that can be sought, found, and trusted. "The truth as I see it" instead means that I leave open the possibility that I might be wrong, or—as in the story of the blind men and the elephant—at least not seeing the whole truth. In fact, I'd say it's pretty much guaranteed that I'm not seeing the whole truth. But what I do see, from over seven decades of experience, and a reasonable amount of both intelligence and education, I will say.

Because the world has been turned upside down, and an astonishing number of people either don't see what is happening, or don't have the time and the resources to care, or truly believe that the inversion is finally putting the world to rights.

If the whole world says that war is peace, freedom is slavery, and ignorance is strength, I'm going to reply, No, it isn't. Fortunately, it's not the whole world that's saying such things, just those with the biggest megaphones. More and more people are noticing the emperor en déshabillé, and are speaking up, and when I find someone who makes a point better than I can, I'll share it.

I don't expect this blog to change much; I've never been known for keeping silent when I have an opinion. But now these thoughts have their own category: Here I Stand. It is related to my Last Battle series, which I tried to start in 2018; it finally got off the ground in 2020, but is still struggling. I don't usually have trouble putting my thoughts into words, but this category makes me think there might be something to Stephen Pressfield's idea that there is an active force (he calls it "Resistance") that opposes creative activity. All too often, the more important I think an idea is, the harder I find writing about it. If this one works out, maybe I'll merge the two categories, or connect them somehow. But first things first.

I see my mission as to seek and speak the truth. I'm not going to argue, I'm not going to debate, I'm not going to insist. I must speak, but no one is required to listen.

If you have read C. S. Lewis's story, The Silver Chair, you may recall that after the Prince is freed from his enchantment, the Witch attempts to get him and his liberators to deny all they know about the world they came from, and what they remember from their former lives. (It's in Chapter 12, and you can read that here.) If my writing smells like burnt marsh-wiggle to some, I hope that others will find it helps to clear away some of the enchanting smoke. If nothing else, I want to be able to say with Drucker, "Of course it had no inmpact. I did not expect any. But it made it crystal-clear where I stood; and I knew I had to make sure for my own sake that I would be counted, even if no one else cared."

Permalink | Read 1488 times | Comments (0)

Category Last Battle: [first] [previous] [newest] Here I Stand: [next] [newest]

For those of you waiting to hear about Grace's return to her home in New Hampshire after more than two months of exile in Boston, I'll quote Heather's post in its entirety (emphasis mine).

Happy, Happy, Happy!

Grace sings this little Happy song at least once a day. She sang it in the hallway as we were leaving the apartment to go home. I have not yet managed to get a video of her singing it.

Everybody is doing better now that we're all together.

It's good to be home; it's good to not have to try to get a bunch of stuff done before leaving again. We are still adjusting to the routine, and still unpacking, but the overall feeling is good.

There is a lot of laughter in the house with Grace around. She is such a blessing.

Please continue to pray for her complete healing and protection from germs.

Permalink | Read 1176 times | Comments (0)

Category Pray for Grace: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

As spring begins to make its welcome way into the Northeast, here's a reminder to those of you who love winter of how nice it can be. Can you beat riding out a snowstorm in an off-grid cabin you built yourself?

I love this guy's videos. I don't know why, but I find them so relaxing, almost meditative. So when I need a little de-stressing, they're a good break.

Permalink | Read 1186 times | Comments (0)

Category Everyday Life: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

If you are not among those of our family and friends who are travelling to view the solar eclipse, or who are lucky enough to live in the path of totality, you can still enjoy this facsimile. (Image found on Facebook.)

Here in Florida we are a lot further away from the path of totality than on March 7, 1970, when I lived in Philadelphia and the path was just off the coast. Here's how my father described it then:

On Saturday we watched the eclipse by focussing the light from the sun on a piece of paper through half of our binoculars. It worked well, and the progress of the moon was very clear. At the darkest, it looked like a heavily overcast day outside, so it was not really impressive for this time of the year, but what we didn't see here we did see on television.

Permalink | Read 1155 times | Comments (0)

Category Just for Fun: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Glimpses of the Past: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

All continuing to go well, Grace will return to her New Hampshire home on Monday! This is huge for her and for the whole family.

She will need to return to Boston once or twice each week for clinic visits. At some point, the Dartmouth hospital should be able to handle some of the appointments, but for now, they've decided it's worth the long drives to be able to have the family all together. After all, they've been driving almost that much going the other direction while living in Boston.

Grace has had less nausea, has gotten her formula intake down to 16 ounces per day, is eating more on her own, and is steadily gaining weight. Thanks be to God and all your prayers!

Please pray for:

- Continued progress for Grace

- A smooth transition back to being a family all together.

- Wisdom for Heather, Jon, and the doctors as they figure out the best way to keep Grace healthy while reintegrating her into normal family life.

- Strength for Heather as she handles the normally-exhausting late stages of pregnancy.

- The birth and the baby. I'm rooting for a girl, and in my mind I've already named her "Hope"—but I have a less-than-stellar batting average when it comes to baby guesses.

Grace's next milestone will be the three-month mark (May 8), where if all things continue to go well, her transplant will be considered to be successful. It's only the next of many more steps, but it's an important one.

Permalink | Read 1231 times | Comments (1)

Category Pray for Grace: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

You need to get out of your comfort zone.

How often have you heard that advice? Or given it?

It sounds good, as do most dangerous ideas that contain a bit of truth.

Doing hard things can lead to physical, mental, and spiritual growth. But it can also break you. Children grow best when we give them plenty of opportunity to stretch their abilities—not by subjecting them to the rack. That goes for adults, too.

Here's the thing: For many people, living ordinary, daily life is out of their comfort zone, and they get all the growth opportunities they need just making it through the day. Let me say that again.

For many, daily life is out of their comfort zone.

I guarantee that you know people for whom that is true. It may very well be true for you; if not all the time, at least on occasion. The catch is, none of us knows where someone else is in this. We have no idea how hard someone may be working to make it seem as if his life is easy—or even bearable. And that's okay. Life is hard, and growth comes out of the struggle. As long as we remember that it's not our job to push someone else out of his own comfort zone. I know a woman who learned to swim by being thrown out of a boat in the middle of a lake. A lake with alligators. She lived, but I don't recommend the method.

In my experience, when someone tells another person, "You need to get out of your comfort zone," he's less interested in helping that person grow than in getting a particular job done. And hoping that a combination of guilt and the prospect of personal growth will push the reluctant victim to accept. Don't do that.

Push yourself? That's great. Reaching, stretching, working hard, and overcoming difficulties can be good for you and for the world—and it usually feels fantastic (in the end; not always in the middle). But when someone else insists you need to get out of your comfort zone, take it with a grain of salt. Sometimes pain can indeed lead to gain, but it is more likely to lead to injury. And for sure, don't say such a thing to others.

Comfort zone? Comfort zone? Where does that idea come from, anyway? I'll take a poll: Who here are feeling relaxed and comfortable with their lives? Raise your hands. I didn't think so.

There's work to be done in this world, and duty calls us all. Difficult tasks and decisions come to us every day, nolens volens. This is not a call to shirk our responsibilities, but to know ourselves and to respect the needs of our fellow-strugglers.

Christ is risen!

The Lord is risen indeed!

Alleluia!

Easter was not a surprise, nor an afterthought, nor a Plan B. In the drama of Holy Week, all scenes—from Palm Sunday through Maundy Thursday, Good Friday, and Holy Saturday—point toward the climax of the story: Easter. The Author includes some dark, excruciating (literally) moments, but the triumphant last scene is never out of His sight.

Jesus Christ is ris′n today, Alleluia!

Our triumphant holy day, Alleluia!

Who did once upon the cross, Alleluia!

Suffer to redeem our loss. Alleluia!

Hymns of praise then let us sing, Alleluia!

Unto Christ, our heav'nly King, Alleluia!

Who endured the cross and grave, Alleluia!

Sinners to redeem and save. Alleluia!

But the pains which He endured, Alleluia!

Our salvation have procured, Alleluia!

Now above the sky He′s King, Alleluia!

Where the angels ever sing. Alleluia!

Permalink | Read 1190 times | Comments (0)

Category Everyday Life: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Inspiration: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

Easter's coming, but it's not here yet. (Except in Switzerland, and some other time zones.)

Permalink | Read 687 times | Comments (0)

Category Just for Fun: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

In view of the trials our family has been experiencing recently, and because it has been fourteen years since I published it in 2010, I decided to bring back a previous Good Friday post.

Is there anything worse than excruciating physical, mental, emotional, and spiritual torture and death?

It takes nothing from the sufferings of Christ commemorated this Holy Week to pause and consider a couple of other important persons in the drama.

I find the following hymn to be one of the most powerful and moving of the season. For obvious reasons, it is usually sung on Palm Sunday, but the verses reach all the way through to Easter.

Ride on! ride on in majesty!

Hark! all the tribes hosanna cry;

Thy humble beast pursues his road

with palms and scattered garments strowed.

Ride on! ride on in majesty!

In lowly pomp ride on to die;

O Christ, thy triumphs now begin

o'er captive death and conquered sin.

Ride on! ride on in majesty!

The angel armies of the sky

look down with sad and wond'ring eyes

to see the approaching sacrifice.

Ride on! ride on in majesty!

Thy last and fiercest strife is nigh;

the Father on his sapphire throne

expects his own anointed Son.

Ride on! ride on in majesty!

In lowly pomp ride on to die;

bow thy meek head to mortal pain,

then take, O God, thy power, and reign.

"The Father on his sapphire throne expects his own anointed Son." For millennia, good fathers have encouraged, led, or forced their children into suffering, from primitive coming-of-age rites to chemotherapy. Even when they know it is for the best, and that all will be well in the end, the terrible suffering of the fathers is imaginable only by someone who has been in that position himself.

And mothers?

The Protestant Church doesn't talk much about Mary. The ostensible reason is to avoid what they see as the idolatry of the Catholic Church, though given the adoration heaped upon male saints and church notables by many Protestants, I'm inclined to suspect a little sexism, too. In any case, Mary is generally ignored, except for a little bit around Christmas, where she is unavoidable.

On Wednesday I attended, for the second time in my life, a Stations of the Cross service. Besides being a very moving service as a whole, it brought my attention to the agony of Mary. Did she recall then the prophetic word of Simeon, "a sword shall pierce through your own soul also"? Did she find the image of being impaled by a sword far too mild to do justice to the searing, tearing torture of watching her firstborn son wrongly convicted, whipped, beaten, mocked, crucified, in an agony of pain and thirst, and finally abandoned to death? Did she find a tiny bit of comfort in the thought that death had at least ended the ordeal? Did she cling to the hope of what she knew in her heart about her most unusual son, that even then the story was not over? Whatever she may have believed, she could not have had the Father's knowledge, and even if she had, would that have penetrated the blinding agony of the moment?

In my head I know that the sufferings of Christ, in taking on the sins of the world, were unimaginably greater than the physical pain of injustice and crucifixion, which, awful as they are, were shared by many others in those days. But in my heart, it's the sufferings of God his Father and Mary his mother that hit home most strongly this Holy Week.

Permalink | Read 1169 times | Comments (1)

Category Children & Family Issues: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Everyday Life: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Pray for Grace: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

I love my dad's sense of humor.

Here's another story from his journals, this time from a four-week cross-country car trip we took in the summer of 1968. When we weren't visiting relatives, we camped in a small tent-trailer, at inexpensive campgrounds. Some were wonderful, most were fine, and a few were less so. Of the North Woods Motor Court and Campground, which as far as I can tell no longer exists, Dad said,

It looks like the owner is fixing things up in his spare time, and he hasn't had much spare time.

There were only two picnic tables, and one bathroom. But with only four families staying, that worked out all right, and we were just thrilled to be camping on green grass for the first time in quite a while. It's only worth writing about because Dad's comment makes me laugh.

And also because this campground was the scene of our Great Skunk Adventure, but that is another story.

Permalink | Read 999 times | Comments (1)

Category Just for Fun: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Glimpses of the Past: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

Here's another observation from reading my father's journals, this one from April 1963.

About 11 a.m. I went out to the car to go out to the Research Lab and the car ('57 Ford) wouldn't start. It was not firing at all. I spent the better part of the lunch hour convincing myself there was no spark. Blackie (the guard at the Building 37 gate) called the man from the GE garage who diagnosed it as a bad condenser.

Since he was not in a position to make repairs, I called the AAA for the first time in years. On the telephone I told the girl that it was not a dead battery and that the trouble had been diagnosed as a bad capacitor. I had hoped this would at least forewarn the man who came, even though he would no doubt want to make his own diagnosis. So in about half an hour he showed up with the question, "What's the matter? Dead battery?"

All he would do was to diagnose the trouble as a bad coil and tow me somewhere. I had him tow me to Dorazio's service station where I left the car to get yet another diagnosis.

Fifty years later and customer service experiences don't look much different. Especially if you try to give them information or ask them to go off-script. After much phone time and several questionable attempts at a fix, a well-known bank is still sending us multiple copies of each e-mail, and they are not interested in hearing what we already know about the problem.

Permalink | Read 954 times | Comments (0)

Category Random Musings: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Glimpses of the Past: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

I don't have time this morning to do the post justice, but before I start off on our day of adventure I must pass on a specific prayer request for Grace today: She is scheduled for a bone marrow aspiration. In Heather's words: This includes anesthesia and intubation and all that goes along with that. Please pray for her surgery and for the results. Thank you.

Grace's first day of freedom—or rather, more freedom than she has had in well over a month—went well, for the most part. You can read much more about it here. And see some photos here. The hard part was returning to the hospital for a clinic visit. Boston Children's is great with children in so many ways, but there are some holes, and this was one of them. The poor child had tasted freedom for less than 24 hours when she found herself back in the hospital again, not in friendly 6 West, but in a place not suited for her situation. Because of her newborn immune system, she was not allowed to go to the Resource Room with toys and books, but was confined to the small clinic room with nothing to do but wait, and wait, and wait.

Imagine how she must have felt. Heather says she leaned her head against the door and cried, and cried, and screamed. She had endured all that went before with incredible patience and grace and a great attitude—and now this.

However, Heather was able to persuade a nurse to bring her some books. And next time they will be better prepared; one thing Boston Children's is less good at is communication about what is going to happen!

The good news is that medically the clinic visit was uneventful.

Settling in to life "outside" is taking some adjustment, but is happening. They even dealt successfully with their first NG tube clog.

When Grace woke up, we saw that her food bag was still full! Her NG tube had clogged. Both of us tried to flush it with no success. Jon had a terrible time getting through to the right people at the clinic (and that mis-routing of request ended up getting escalated to superiors.) By the time the right person called back to schedule an appointment to put in a new NG tube, Jon had tried again and this time successfully unclogged it! By the way, the nurse said, "Try Coke; we've had great success unclogging tubes with it," and Jon says that's the first time he's been in a store debating about the medicinal qualities of brand name vs. generic coke....

And here is the heart healing part. Look at this wonderful picture!

Permalink | Read 1293 times | Comments (2)

Category Pray for Grace: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

.jpg)