Lenore Skenazy has a new site (relatively new—I've fallen a bit behind) called Let Grow. I haven't explored much yet, but the Let Grow Resolution deserves all the publicity it can get, so I'm (uncharacteristically) lifting it in its entirety here.

The “Let Grow” Resolution:

Our children have the right to some unsupervised time, and we have the right to give it to them without getting arrested.

Statement of findings

- It is good, healthy and normal for kids to walk and play outside, and run some errands on their own.

- Violent crime is at a 50 year low.

- It is not low because we are keeping kids inside. All crime — even against adults — is lower now, and we are not keeping adults inside.

- The risk of child abduction by strangers is very low.

- Being in a car accident as a passenger is the leading cause of death among children, not stranger danger.

- Lack of exercise is a contributing factor to short term and long term health risks for children.

- It is in the public interest for children to walk and cycle to their day-to-day destinations, and to play outside on their own.

- When kids do that, they learn social skills, problem-solving, creativity and compromise — the skills they will need in college and beyond that they do not get in adult-run activities.

- Because we can’t always prepare the path for our children, we must prepare our children for the path, by giving them freedom and responsibility, so they gradually learn to be independent, resourceful and resilient.

Right of Children to Freedom of Movement

- Therefore, this legislature decrees that it supports letting children walk, cycle, take public transportation and/or play outside by themselves, with the permission of a parent or guardian.

- Allowing children to exercise these rights shall not be grounds for charges against their parents or guardians unless something else is found to be amiss.

Questions, comments? Contact Lenore Skenazy at Lenore@LetGrow.org .

Permalink | Read 2010 times | Comments (0)

Category Children & Family Issues: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

That word above all earthly powers, no thanks to them, abideth;

The Spirit and the gifts are ours through Him Who with us sideth:

Let goods and kindred go, this mortal life also;

The body they may kill: God’s truth abideth still,

His kingdom is forever.

Mostly, I like the great Reformation hymn, Martin Luther's A Mighty Fortress Is Our God. Good music, powerful words.

Too powerful. I have a problem singing the middle line of the above verse: Let goods and kindred go, this mortal life also. Usually I manage to sing it by faith, but sometimes thinking about beloved kindred causes me to choke into silence. I'm pretty sure my devoted Christian friends, strong as ever in their faith, are still choking a bit as they watch their two and a half year old son struggle in his battle with leukemia. The hymn is still true: The body they may kill: God’s truth abideth still, His kingdom is forever. It's just hard sometimes.

But I really thought my problem was with the kindred part. I didn't think I'd have so much trouble letting the goods go.

We are in the process of replacing our stove, which has served us exceedingly well for over 40 years. Eventually I may tell the story of its replacement, but first things first.

It was a General Electric stove, one of the very first with a regular oven on the bottom and a microwave oven on the top, and we bought it as part of improving a decidedly-unacceptable kitchen in our very first house, in Rochester, New York. At a price of something over $700, it was quite a splurge back in 1977, but if you ignore the cost of electricity and a couple of repairs, that works out to less than $20 per year for roasting meats, simmering stews, baking bread, boiling eggs, and making cookies and birthday cakes.

It still worked, mostly, after 40 years. The automatic oven cleaning feature started to get a little wonky, so we disabled it in 2001 when we temporarily rented the house out during our time living in Boston. When we returned in 2003, we left it that way in the interest of safety. The part of the oven door that holds it up when open went on strike, and after a couple of strikebreaking efforts that didn't last long, I learned to hold the door with a strategically placed knee as I maneuvered food in and out of the oven. A few years ago, the front left burner stopped working, and defied attempts to diagnose the problem. But it was when the two back burners started to act up that we decided, reluctantly, that it might be time to think about a replacement.

There's a saying, attributed to George Bernard Shaw, that if you lined up all the economists in the world end to end, they still wouldn't reach a conclusion. The same has been said about Langdons. I am a chief example, and the stove decision was no exception. Partly because I find shopping—even online, though that's better—absolutely agonizing, and partly because, well, because the stove still worked. When you have a working microwave, an oven that can bake and roast and broil, and one and two-halves burners, what's the rush? We started our new stove search well over a year ago, and the reason the search reached a conclusion at this most inconvenient time of the year is the Porter decided that I must make the decision now. So I did—I hadn't been wasting all those months and had done a fair amount of preliminary work—but as I said, the new stove is later story.

I'm happy with the new stove, but it was still a wrench to let the old stove go. It was foolish, perhaps, but I cleaned it one more time, with a heart full of thanksgiving: a labor of love, like that of women in bygone days who gently prepared the bodies of their departed for burial. If we could have found it a good home, as we did with the 1999 Chevy Venture we recently had to part with, I'd have been okay. But we learned long ago that no one is so poor as to desire our cast-off furniture, including appliances that work much better than this old stove. I mean, I know people really are that poor, but charities are not interested in meeting their needs in that way. Our city wouldn't accept it for recycling or even hazardous waste, but did give Porter the name of a company that buys old appliances. Great! we thought, even though we had to transport it to their site ourselves.

Which Porter did, today. And discovered that they weren't interested at all in the fact that much of it was still operational; all they wanted was the scrap metal. They paid him 14 pieces of silver—I mean dollars. That was better than our having to pay someone to dispose of it, but my heart breaks to think of our faithful stove, which could still do most of what it had been created for, crunched up into a small metal cube.

Let goods and kindred go. Right. If I can't even do it for a 40-year-old appliance....

Permalink | Read 1953 times | Comments (6)

Category Random Musings: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

At first I didn't participate in the "Me Too" campaign on Facebook (and elsewhere)—meant to reveal the magnitude of the problem of sexual harassment and assault in our country and now featured in Time magazine's "Person of the Year"—because, well, because I'm not a joiner, and I don't like chain letters, even if they don't promise me that blessings will come my way if I pass it on, and that misfortune is sure to follow if I don't.

Later, I thought it might not be such a bad idea to highlight a problem that has been ignored too long. Here's the Facebook exchange that started my thinking:

S: Me Too.

If all the women I know who have been sexually harassed or assaulted wrote "me too" as a status... and all the women they know... we might give people a sense of the magnitude of the problem.

Stop the silence. Stop the violence.

L: How do you define, "harassed"? There are days when I feel that being whistled at while walking down the street, or approached by a stranger trying to pick you up, is sexual harassment. And how about being kissed too familiarly by a drunk relative? "Felt up" by an overeager teenaged boyfriend at the movies? I could understand the last two being called assault, but I suspect many people wouldn't. At any rate, all of the above are unwelcome and ought to stop. But they are so many orders of magnitude below rape and other forms of what is clearly sexual assault, that I fear to muddy the waters and appear disrespectful of the pain of the latter victims. What is your take on this?

K: My view is this: any time one individual relates to another individual on an exclusively sexual plain, that individual demeans the other and diminishes their humanity. Although there are many degrees of disregard, the bottom line is that one person is being treated as something less than fully human. It's a way of thinking about people that is at the heart of sexism, racism, ageism, etc. As a human society we must insist on asserting the wrongness of that way of thinking. At school we define sexual harassment as any action of a sexualized nature that makes the target feel uncomfortable - from whistling to name calling to inappropriate touching to lifting someone's clothing and much more. It is important not to confuse harassment and assault. And important to distinguish what is legally prosecutable from what isn't. But we make too many excuses and allowances for behavior that is unacceptable. I think it is time to draw the lines about unacceptable behavior that falls short of rape far more clearly than we do.L: I think life has gotten a lot harder since the 1960's. I could certainly say "me too" to the definitions of harassment you've given. But nothing compared with what I hear from others ... and no worse than non-sexual harassment, which I would call plain rudeness.

That was helpful, but I wasn't convinced. I have friends who have to live with that kind of pressure in their work environment, or have actually been raped, and I didn't think it right to put my own experiences in the same category as theirs. Mine fell into the more general category of "bullying," though with a sexual dimension, because bullies will strike wherever they find a weakness. That, and "the guy was too drunk to know what he was doing, and would be mortified if he knew." It seemed like putting into the same category of "wounded in the war" both the man whose arm was nicked by a piece of shrapnel and the one who had both legs blown off. It's true, but is it helpful?

The broader definition of sexual harassment certainly cuts right to the heart of the problem, and goes along with what Jesus said about both lust and murder. But is it helpful to draw the line around all women, at least of a certain age, and quite a few men as well? Maybe—but I still didn't feel I could participate.

And then, today, I remembered.

I made the comment, in a discussion at choir rehearsal last Sunday, that one of our members, who teaches physical education, sure doesn't fit the stereotype of a female gym teacher. And I got to thinking about what I thought of as a stereotypical female gym teacher, and remembered the bane of my existence from high school.

I've repressed a lot of memories from high school gym class, and I won't name names because I really have managed to forget many of the details. But if the teachers, themselves, were not outright abusive (though it felt like it to me), the system that they participated in certainly was. I suspect it was not uncommon at the time, and it certainly never occurred to me that it was something I could successfully object to—it was just one of the many miserable things teachers were allowed to do to students.

And lest you be wondering what fearful revelations I'm about to make, I'll relieve your minds: It may even seem minor to you, and I don't think I bear any significant scars, other than those inflicted by gym class in general. But there's no doubt in my mind, looking back, that it was an abusive, even a sexually abusive, situation.

By the time we were in high school, we were required to take showers after gym class. I could see it for the guys, but we girls almost never perspired enough to need showers—and the process wouldn't have gotten us clean if we had. No doubt gym class has changed over the years; I certainly hope the bathing situation has.

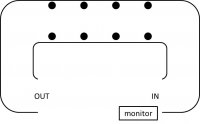

This is a rough plan of the shower room. Stripped naked, we were forced to give our names to a student monitor, who dutifully checked us off, then walk through a gauntlet of shower heads and out the exit. That's it. No soap—it slows down the line. In fact, the object was to run through as quickly as possible, minimizing our exposure to both water and the prying eyes of everyone else in the room. It was bad enough that we had to change into and out of our gym clothes in a public locker room, but the showers were an extra refinement of torture. Once a month we were allowed to avoid that humiliation, but that required us to announce to the monitor, and all within earshot, that we were having our periods.

This is a rough plan of the shower room. Stripped naked, we were forced to give our names to a student monitor, who dutifully checked us off, then walk through a gauntlet of shower heads and out the exit. That's it. No soap—it slows down the line. In fact, the object was to run through as quickly as possible, minimizing our exposure to both water and the prying eyes of everyone else in the room. It was bad enough that we had to change into and out of our gym clothes in a public locker room, but the showers were an extra refinement of torture. Once a month we were allowed to avoid that humiliation, but that required us to announce to the monitor, and all within earshot, that we were having our periods.

If our gym teachers had been male, no one would question that this situation was wrong. I fail to see that them being female made the forced exposure of our young bodies and private matters to their eyes and those of the entire class any more acceptable.

Age, and having gone through the process of giving birth to our children, have since made me less sensitive to what other people see and think, but I still appreciate the private changing areas that are now provided in public pools and gyms. No one—especially no pubescent child—should have to go through what I, and my classmates, endured.

So yes, "Me, too." It's insignificant compared to what others have experienced, but it's part of a pattern of disrespect that needs to end. Jesus had it right, you know. It's our heart attitude that matters. When we wink at smaller offenses, we promote an atmosphere in which heinous acts proliferate.

It's time for national repentance, and a good place to begin would be with the highest office in the land. If that's not forthcoming—a grassroots effort is probably better, anyway.

Permalink | Read 1781 times | Comments (1)

Category Children & Family Issues: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Random Musings: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

I haven't forgotten my Seven Days of Thanksgiving series. Those posts take more time to write than I have right now ... maybe I'll finish by Christmas, because, of course, I'm sure to have more time as that day approaches, right?

In the meantime, here's a short TED talk that my friend Ashley shared on Facebook. It says several important things about how to have a good conversation in an age where those are becoming increasingly rare.

I see plenty for me to learn here. I think face-to-face conversations are especially difficult for introverted writers. The illustration where the guy asks, "How are you today?" and the girl responds, "Read my blog!"—that's me all over. It's hard to converse, or even want to converse, when you know that you can answer someone's question so much more coherently if you could only have a few minutes to write your response! On the flip side, that makes us more eager to listen than to talk. I don't want to hear my own stories; I know them already. I want to hear other people's stories.

Permalink | Read 1787 times | Comments (0)

Category Random Musings: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

With the engagement of Prince Harry and Meghan Markle making the news, and my old friend Gary Boyd Roberts* and the New England Historic Genealogical Society providing temptation in the way of an article and a handy genealogy chart, I decided to spend some time trying to link their data with my own. And indeed, I could. As it turns out, Meghan Markle is my 23rd cousin, once removed, with common ancestors King Edward I of England (Longshanks) and Eleanor of Castile, through American immigrant ancestor Robert Abell. Through the same common ancestors (but a mostly different line on his part, of course), I am also Prince Harry's 23rd cousin, once removed. Yes, this means that Prince Charles is my 23rd cousin, and Queen Elizabeth II is my 22nd cousin, once removed. Who knew?

Similarly, Porter is 23rd cousin three times removed to both of them, with common ancestor King John (Lackland) of England and his mistress, Clemence, through the American immigrant ancestor Thomas Yale.

Not that I can claim anything special in all this. Millions of Americans are cousins to the new royal couple. They just don't know it—as I did not until now. But I love puzzles, and have finally learned—no thanks at all to my school experiences—that history is fascinating.

It's time to bring back this quote from Joel Salatin.

On every side, our paternalistic culture is tightening the noose around those of us who just want to opt out of the system. And it is the freedom to opt out that differentiates tyrannical and free societies. How a culture deals with its misfits reveals its strength. The stronger a culture, the less it fears the radical fringe. The more paranoid and precarious a culture, the less tolerance it offers. When faith in our freedom gives way to fear of our freedom, silencing the minority view becomes the operative protocol.

Permalink | Read 1884 times | Comments (0)

Category Inspiration: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

This is the third time I've used that handy title for a post. It may be recursive.

The inspiration for this occasion is a lament from Village Diary, by Miss Read (Dora Jessie Saint). What is remarkable is not the sentiment, but that it was written in 1957.

The child today, used as he is to much praise and encouragement, finds it much more difficult to keep going as his task gets progressively long. Helping children to face up to a certain amount of drudgery, cheerfully and energetically, is one of the biggest problems that teachers, in these days of ubiquitous entertainment, have to face in our schools.

I was going to make this Day of Thanksgiving about music in general, for which I am indeed very thankful. I have to admit that I usually prefer to listen to instrumental, rather than vocal, music. But there is something about singing that sets it apart. Nothing can be more personal than when your instrument is your own body. It's very handy, too: your instrument is with you wherevery you go, and no one makes you check it with the luggage when you fly. On the other hand, a flute never catches the flu....

Best of all, singing is accessible. If there's ever been a culture that doesn't sing, I've never heard of it. Little children sing with great joy, at least until someone's unkind comment convinces them that they can't. With very, very few exceptions, people who say they can't sing—like people who say they can't do math—are victims either of someone's deliberate cruelty or of someone's poor teaching. Even those too embarrassed to sing in front of others can enjoy singing in the shower.

My father was always told as a child that he couldn't sing. I'm not a fan of college fraternities, but his story reminds me that not all fraternities fit the stereotype.

My parents felt that since I would be living at home I should join a fraternity in order to have some on-campus experiences. First I was rushed by my father’s former fraternity, but to me it seemed to contain all the undesirable elements of fraternities—they boasted about how many football players were members, how many parties they had, an atmosphere that bothered me—and I quickly lost interest. Later a faculty friend suggested his former fraternity and while I liked it better it still didn’t really appeal to me. About mid year I became acquainted with Alpha Kappa Lambda, a fraternity whose members neither smoked nor drank and that one I joined.

Nearly a third of the fraternity membership comprised music majors, and they prided themselves on their fine fraternity chorus. I no sooner had committed myself to the fraternity than the chorus director asked me what part I sang. I had always known that I could not sing and people, including my parents, never hesitated to tell me that I couldn’t sing. So that was my reply to the director. He called me over to the piano and had me sing scales and other notes as he played them. After several minutes of this he said, “You are a second tenor.” Thus I became a member of the chorus. He had recognized that although I did not have a solo voice, I could match the piano tones accurately and thus could follow others and blend in with their notes.

This meant a great deal to me and brought much pleasure. And I owe much to the chorus leader for leading me into singing. In college the chorus sang quite often for various events and it allowed me to find a place in the church choir. And all three years I sang with the chorus we took first place in the annual competition among living group choruses. It also meant much to me after I left college....

| "Did you know that singing and talking involve two different parts of the brain? People who have lost speech due to a stroke can often still sing. Stutterers can usually sing fluently. The local pizza shop recognized a friend of mine by the fact that she would sing her pizza order." |

Dad sang with a barbershop quartet after college, but what I remember best is his singing at home, usually folk songs, from Old World ballads to sea shanties to cowboy laments. That's a great gift to give a child. I wish I had given it to my own children, but I'm not as resilient as my father was, and still bear my own scars, from wounds inflicted by my junior high school music teacher (who was also—until she drove me out—my church children's choir director; it was a very small town).

Singing knits people together. It's a tragedy that family singing is a lost art. But that is one singing gift we were able to give our own children—not that we gave the gift, but we did put them (and ourselves) in a position to receive it. We have a set of musical friends with whom nearly every get-together ends with people gathered around the piano, singing. That's my idea of a party! Depending on who is present, and the time of the year, the music may be choir anthems, or hymns, or Beatles songs, or Christmas carols, or popular music I've never heard of, but it's all wonderful fun. The following video is one example (there are more people behind the camera). It's my video, but I had refrained from posting it rather than bother to get permission from the singers. But now it has been made public, so I figure it's fair game. :) By the way, don't be tempted to think badly of the people staring at their phones—they're reading the song lyrics.

I'm thrilled that our children and grandchildren know the joy of singing together. The adults and several of the children all play the piano, but you don't need that skill to sing as a family. They also sing a cappella. Unaccompanied singing can be beautiful, and teaches a good sense of harmony. And even though it's not my taste, there's always karaoke....

And it's never too early or too late. Children can sing in groups in school. Many churches and communities have children's choirs. The hardest years, I've found, are the middle ones, when one must juggle babies, and children ... and children's schedules. But after that, the opportunities open up again, with church choirs and community choruses. A few church choirs are too good, or require too much of a commitment, for timid singers, but most welcome anyone who will even try to sing on pitch—and the best way I know to learn to sing is to sing with others.

Go. Sing. Lift up your hearts and your voices, with thanksgiving.

Permalink | Read 1777 times | Comments (0)

Category Random Musings: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

This observation needs reviving again, from John Caldwell Holt.

One of the saddest things I've learned in my life, one of the things I least wanted to believe and resisted believing for as long as I could, was that people in chains don't want to get them off, but want to get them on everyone else. Where are your chains? they want to know. How come you're not wearing chains? Do you think you are too good to wear them? What makes you think you're so special?

Permalink | Read 1703 times | Comments (0)

Category Inspiration: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

Clean water, coming freely—hot or cold—at a touch, on demand. Not just for my community, but at our own house—several places in and around our house, in fact. That is wealth unheard of for much of the world, stretching along dimensions of both space and time.

Granted, others have been richer in the taste of their water. In my memory, no water in the world has ever matched that which flowed in the streams of the Adirondack Mountains, where I hiked as a child with my father. Our tap water is bland, with the dull sameness that permeates pasteurized milk, orange juice, and cider, and accompanies produce and meats bred and processed to be convenient, standard, and safe. But tap water is fine with me, because if there's a bottled spring water that even hints at that glorious mountain spring taste, I've never experienced it. In fact, I don't believe it exists, because the processing needed to make it safe to transport and sell kills the flavor along with the germs.

But plentiful, clean water, bland or not, is one of the greatest blessings in the world. Water for drinking, water for cooking, water for washing, water for flushing toilets, water for swimming, water for tea and squirt gun fights and baptisms.

Then there's the other side. All that blessed water flowing in to our homes requires a safe channel to remove it for its own cleansing after it has finished with ours. Sewage removal and treatment is something we usually take for granted—until it stops. The dread of sewage backups keeps us vigilant to minimize our water use during hurricane recovery, and grateful for the emergency generators struggling to keep the county's pumping stations and sewage treatment plants functioning.

I'm reminded of the following, from the Book of Common Prayer's baptismal service:

We thank you, Almighty God, for the gift of water. Over it the Holy Spirit moved in the beginning of creation. Through it you led the children of Israel out of their bondage in Egypt into the land of promise. In it your Son Jesus received the baptism of John and was anointed by the Holy Spirit as the Messiah, the Christ, to lead us, through his death and resurrection, from the bondage of sin into everlasting life.

We thank you, Father, for the water of Baptism. In it we are buried with Christ in his death. By it we share in his resurrection. Through it we are reborn by the Holy Spirit. Therefore in joyful obedience to your Son, we bring into his fellowship those who come to him in faith, baptizing them in the Name of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Spirit.

We thank you, Almighty God, for the gift of water.

Permalink | Read 1662 times | Comments (0)

Category Random Musings: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

Inspired by my previous post, Presents of Mind, and a few incidents this year that left me temporarily without blessings which I usually take for granted, I'm starting a Seven Days of Thankgiving series. They'll be in no particular order. Seven days isn't nearly enough, but—as a good friend keeps reminding me—better done than perfect.

It doesn't take long for a power outage, such as we experienced with Hurricane Irma, to make one realize the blessing of reliable electric power. One of my happiest childhood memories is of an ice storm that forced us to use candles for light, cook over a camp stove, and have the whole family sleep huddled together on the floor by the fireplace. But our power outage didn't affect our water supply, nor our septic system, and it was winter, so there was no need to worry about spoiled food. If the few days it lasted was too short a time for a child's sense of adventure, I'm sure my mother was thrilled when the power came back on. I wasn't the one who had to worry about washing diapers! And there was nothing I could call delightful about a power outage in the middle of a Florida September, other than being provoked to gratitude. I can't imagine what the people of Puerto Rico and other Caribbean islands are experiencing.

Permalink | Read 1752 times | Comments (4)

Category Random Musings: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

The Charlotte, North Carolina, area is home to some of my favorite people, so when I saw that this video came from Charlotte, I was naturally drawn to it. It's under two minutes long, and definitely worth your time.

I don't need to read anyone's comments (it's making the rounds on Facebook) to hear the negative responses: The the lead character is a while, middle class male. His sweet, blonde wife and his adorable two children, one girl and one boy, send him off from his lovely, suburban home to his first-world office job.

Just. Don't. Go. There.

You'll miss everything important.

Build your own mental video (or film it!) with the characters and situations you think it should have.

And be thankful.

I know it's too early for Christmas videos. It's not even Thanksgiving yet, let alone Advent, let alone Christmas. But for some reason I'm not finding the Christmas-decorations-go-up-before-Hallowe'en problem so annoying this year. Maybe I've given up on trying to fit a proper Advent of solemn, thoughtful preparation followed by 12 glorious days of Christmas into modern, secular, American society. But, aside from the maddening habit of ending the playing of Christmas carols at noon on the 25th, this isn't really modern America's fault. Choirs as well as commercial establishments must begin preparations for the Christmas season early, if they hope to make a good showing in December, so I've been singing Christmas music for weeks already. In my childhood days, December 24 often saw saw us engaged in last-minute shopping, and certainly in last-minute wrapping, but that won't do when one's family is a lot further away than over the river and through the woods, and tucking a small gift into a child's stocking late at night may require international travel—without benefit of a reindeer-powered sleigh. I'm actually grateful that Christmas sales started as soon as they did.

Any church musician knows that it's important to get it right—and equally important to be flexible, charitable, and to choose one's battles.

Permalink | Read 1849 times | Comments (0)

Category Random Musings: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

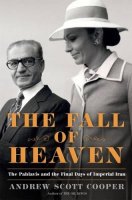

The Fall of Heaven: The Pahlavis and the Final Days of Imperial Iran by Andrew Scott Cooper (Henry Holt, 2016)

The Fall of Heaven: The Pahlavis and the Final Days of Imperial Iran by Andrew Scott Cooper (Henry Holt, 2016)

People were excited at the prospect of "change." That was the cry, "We want change."

You are living in a country that is one of the wealthiest and most powerful in the world. You enjoy freedom, education, and health care that was beyond the imagination of the generation before you, and the envy of most of the world. But all is not well. There is a large gap between the rich and the poor, and a widening psychological gulf between rural workers and urban elites. A growing number of people begin to look past the glitter and glitz of the cities and see the strip clubs, the indecent, avant-garde theatrical performances, offensive behavior in the streets, and the disintegration of family and tradition. Stories of greed and corruption at the highest corporate and governmental levels have shaken faith in the country's bedrock institutions. Rumors—with some truth—of police brutality stoke the fears of the population, and merciless criminals freely exploit attempts to restrain police action. The country is awash in information that is outdated, wrong, and being manipulated for wrongful ends; the misinformation is nowhere so egregious as at the upper levels of government, where leaders believe what they want to hear, and dismiss the few voices of truth as too negative. Random violence and senseless destruction are on the rise, along with incivility and intolerance. Extremists from both the Left and the Right profit from, and provoke, this disorder, knowing that a frightened and angry populace is easily manipulated. Foreign governments and terrorist organizations publish inflammatory information, fund angry demonstrations, foment riots, and train and arm revolutionaries. The general population hurtles to the point of believing the situation so bad that the country must change—without much consideration for what that change may turn out to bring.

It's 1978. You are in Iran.

I haven't felt so strongly about a book since Hold On to Your Kids. Read. This. Book. Not because it is a page-turning account of the Iranian Revolution of 1978/79, which it is, but because there is so much there that reminds me of America, today. Not that I can draw any neat conclusions about how to apply this information: the complexities of what happened to turn our second-best friend in the Middle East into one of our worst enemies have no easy unravelling. But time has a way of at least making the events clearer, and for that alone The Fall of Heaven is worth reading.

On the other hand, most people don't have the time and the energy to read a densely-packed, 500-page history book. If you're a parent, or a grandparent, or work with children, I say your time would be better spent reading Hold On to Your Kids. But if you can get your hands on a copy, I strongly recommend reading the first few pages: the People, the Events, and the Introduction. That's only 25 pages. By then, you may be hooked, as I was; if not you will at least have been given a good overview of what is fleshed out in the remainder of the book.

A few brief take-aways:

- The road to hell is paved with good intentions. Jimmy Carter is undoubtedly an amazing, wonderful person; as my husband is fond of saying, the best ex-president we've ever had. But in the very moments he was winning his Nobel Peace Prize by brokering the Egypt-Israel Peace Treaty at Camp David, he—or his administration—was consigning Iran to the hell that endures today. Thanks to a complete failure of American (and British) Intelligence and a massive disinformation campaign with just enough truth to keep it from being dismissed out of hand, President Carter was led to believe that the Shah of Iran was a monster; America's ambassador to the United Nations, Andrew Young, likened the Shah to Adolf Eichmann, and called Ruhollah Khomeini a saint. Perhaps the Iranian Revolution and its concomitant bloodbath would have happened without American incompetence, disingenuousness, and backstabbing, but that there is much innocent blood on the hands of our kindly, Peace Prize-winning President, I have no doubt.

- There's a reason spycraft is called intelligence. Lack of good information leads to stupid decisions.

- Bad advisers will bring down a good leader, be he President or Shah, and good advisers can't save him if he won't listen.

- The Bible is 100% correct when it likens people to sheep. Whether by politicians, agitators, con men, charismatic religious leaders (note: small "c"), pop stars, advertisers, or our own peers, we are pathetically easy to manipulate.

- When the Shah imposed Western Culture on his people, it came with Western decadence and Hollywood immorality thrown in. Even salt-of-the-earth, ordinary people can only take so much of having their lives, their values, and their family integrity threatened. "It does not do to leave a live dragon out of your calculations."

- The Shah's education programs sent students by droves to Europe and the United States for university educations. This was an unprecedented opportunity, but the timing could have been better. The 1960's and 70's were not sane years on college campuses, as I can personally testify. Instead of being grateful for their educations, the students came home radicalized against their government. In this case, "the Man," the enemy, was the Shah and all that he stood for. Anxious to identify with the masses and their deprivations, these sons and daughters of privilege exchanged one set of drag for another, donning austere Muslim garb as a way of distancing themselves from everything their parents held dear. Few had ever opened a Quran, and fewer still had an in-depth knowledge of Shia theology, but in their rebellious naïveté they rushed to embrace the latest opiate.

- "Suicide bomber" was not a household word 40 years ago, but the concept was there. "If you give the order we are prepared to attach bombs to ourselves and throw ourselves at the Shah's car to blow him up," one local merchant told the Ayatollah.

- People with greatly differing viewpoints can find much in The Fall of Heaven to support their own ideas and fears. Those who see sinister influences behind the senseless, deliberate destruction during natural disasters and protest demonstrations will find justification for their suspicions in the brutal, calculated provocations perpetrated by Iran's revolutionaries. Others will find striking parallels between the rise of Radical Islam in Iran and the rise of Donald Trump in the United States. Those who have no use for deeply-held religious beliefs will find confirmation of their own belief that the only acceptable religions are those that their followers don't take too seriously. Some will look at the Iranian Revolution and see a prime example of how conciliation and compromise with evil will only end in disaster.

- I've read the Qur'an and know more about Islam than many Americans (credit not my knowledge but general American ignorance), but in this book I discovered something that surprised me. Two practices that I assumed marked every serious Muslim are five-times-a-day prayer, and fasting during Ramadan. Yet the Shah, an obviously devout man who "ruled in the fear of God" and always carried a Qur'an with him, did neither. Is this a legitimate and common variation, or the Muslim equivalent of the Christian who displays a Bible prominently on his coffee table but rarely cracks it open and prefers to sleep in on Sundays? Clearly, I have more to learn.

- Many of Iran's problems in the years before the Revolution seem remarkably similar to those of someone who wins a million dollar lottery. Government largess fueled by massive oil revenues thrust people suddenly into a new and unfamiliar world of wealth, in the end leaving them, not grateful, but resentful when falling oil prices dried up the flow of money.

- I totally understand why one country would want to influence another country that it views as strategically important; that may even be considered its duty to its own citizens. But for goodness' sake, if you're going to interfere, wait until you have a good knowledge of the country, its history, its customs, and its people. Our ignorance of Iran in general and the political and social situation in particular was appalling. We bought the carefully-orchestrated public façade of Khomeini hook, line, and sinker; an English translation of his inflammatory writings and blueprint for the establishment of an Islamic republic in Iran came nine years too late, after it was all over. In our ignorance we conferred political legitimacy on the radical Khomeini while ignoring the true leaders of the majority of Iran's Shiite Muslims. The American ambassador and his counterpart from the United Kingdom, on whom the Shah relied heavily in the last days, confidently gave him ignorant and disastrous advice. Not to mention that it was our manipulation of the oil market (with the aid of Saudi Arabia) that brought on the fall in oil prices that precipitated Iran's economic crisis.

- The bumbling actions of the United States, however, look positively beatific compared with the works of men like Muammar Gaddafi of Libya, and Yasser Arafat and his Palestine Liberation Organization, who funded, trained, and armed the revolutionaries.

- The Fall of Heaven was recommended to me by two Iranian friends who personally suffered through, and escaped from, those terrible times.

I threw out the multitude of sticky notes with which I marked up the book in favor of one long quotation from the introduction. It matters to me because I heard and absorbed the accusations against the Shah, and even thought Khomeini was acting out of a legitimate complaint with regard to the immorality of some aspects of American culture. Not that I paid much attention to world events at the time of the Revolution, being more concerned with my job, our first house, a visit to my in-laws in Brazil, and the birth of our first child. But I was deceived by the fake news, and I'm glad to have a clearer picture at last.

The controversy and confusion that surrounded the Shah's human rights record overshadowed his many real accomplishments in the fields of women's rights, literacy, health care, education, and modernization. Help in sifting through the accusations and allegations came from a most unexpected quarter, however, when the Islamic Republic announced plans to identify and memorialize each victim of Pahlavi "oppression." But lead researcher Emad al-Din Baghi, a former seminary student, was shocked to discover that he could not match the victims' names to the official numbers: instead of 100,000 deaths Baghi could confirm only 3,164. Even that number was inflated because it included all 2,781 fatalities from the 1978-1979 revolution. The actual death toll was lowered to 383, of whom 197 were guerrilla fighters and terrorists killed in skirmishes with the security forces. That meant 183 political prisoners and dissidents were executed, committed suicide in detention, or died under torture. [No, I can't make those numbers add up right either, but it's close enough.] The number of political prisoners was also sharply reduced, from 100,000 to about 3,200. Baghi's revised numbers were troublesome for another reason: they matched the estimates already provided by the Shah to the International Committee of the Red Cross before the revolution. "The problem here was not only the realization that the Pahlavi state might have been telling the truth but the fact that the Islamic Republic had justified many of its excesses on the popular sacrifices already made," observed historian Ali Ansari. ... Baghi's report exposed Khomeini's hypocrisy and threatened to undermine the vey moral basis of the revolution. Similarly, the corruption charges against the Pahlavis collapsed when the Shah's fortune was revealed to be well under $100 million at the time of his departure [instead of the rumored $25-$50 billion], hardly insignificant but modest by the standards of other royal families and remarkably low by the estimates that appeared in the Western press.

Baghi's research was suppressed inside Iran but opened up new vistas of study for scholars elsewhere. As a former researcher at Human Rights Watch, the U.S. organization that monitors human rights around the world, I was curious to learn how the higher numbers became common currency in the first place. I interviewed Iranian revolutionaries and foreign correspondents whose reporting had helped cement the popular image of the Shah as a blood-soaked tyrant. I visited the Center for Documentation on the Revolution in Tehran, the state organization that compiles information on human rights during the Pahlavi era, and was assured by current and former staff that Baghi's reduced numbers were indeed credible. If anything, my own research suggested that Baghi's estimates might still be too high. For example, during the revolution the Shah was blamed for a cinema fire that killed 430 people in the southern city of Abadan; we now know that this heinous crime was carried out by a pro-Khomeini terror cell. Dozens of government officials and soldiers had been killed during the revolution, but their deaths were also attributed to the Shah and not to Khomeini. The lower numbers do not excuse or diminish the suffering of political prisoners jailed or tortured in Iran in the 1970s. They do, however, show the extent to which the historical record was manipulated by Khomeini and his partisans to criminalize the Shah and justify their own excesses and abuses.

On our cruise to Mexico and Cuba with two of our grandchildren we were given a quick lesson in napkin folding. Naturally, the kids picked up on it better than the adults. This morning, a friend shared on Facebook a video of napkin folding techniques from the Ever & Ivy site. Unfortunately, I can't find the video on YouTube, so I can't embed it here, but hopefully the link will still work when I want to find it again. (There are also plenty of other napkin-folding instructional videos on YouTube.) Warning: I'm sure there are other good things about the Ever & Ivy site, but I can't recommend it in general. Good ideas + Bad language = I'll find the good ideas elsewhere, thank you. Except for the napkin folding—no words.

Permalink | Read 1825 times | Comments (0)

Category Just for Fun: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

It's all too easy, when one's eyes and mind are blurred by immersion in a sea of birth, death, and marriage data (or worse, the lack thereof), to forget that our ancestors were real people who laughed and cried and joked, just as we do. Then, every once in a while, you come upon something that wakes you up, such as a comment from Dr. Lewis Newton Wood, my great-great-great grandfather.

Lewis Newton Wood, son of David and Mercia (Davis) Wood, was born in southern New Jersey, on January 12, 1799. In 1821 he married Naomi Dunn Davis, born September 8, 1800, the daughter of David and Naomi (Dunn) Davis. Their first child, my great-great grandfather, was born in New Jersey, but the other seven of their children were born after they moved to upstate New York, near Syracuse. There, Lewis taught school, and in 1836 he graduated from the newly-formed Geneva Medical College, then part of Geneva College, which is now Hobart and William Smith. The medical school itself is now SUNY Upstate University. Perhaps the most famous graduate of the Geneval Medical College is Elizabeth Blackwell, Class of 1849, America's first licensed female physician.

Lewis moved to Chicago to practice medicine, and his family followed a year later, after which they migrated some 90 miles northwest to become some of the earliest settlers of Walsorth, Wisconsin. Eighteen years later they moved to their final destination, about 100 miles further north and west, to Baraboo, Wisconsin. There, Lewis died in 1868, and Naomi in 1883; they are buried in the Walnut Hill Cemetery in Baraboo. My great-great grandfather, incidentally, continued the family's northward and westward migration, moving first to the Upper Peninsula of Michigan, and finally to the west coast of Washington.

Lewis was not only a teacher, doctor, pioneer, and probably farmer (given that he lived on 360 acres in Big Foot Prairie), but also an amateur geologist who made notable scientific contributions, one of the founders of a school of higher education for girls in Baraboo, and a member of the Wisconsin state legislature. He even has his own Wikipedia entry, a link I incude with the standard Wikipedia cautionary tale about not believing everything you read, since some of the facts about him are wrong.

After that historical and genealogical excursion, I arrive at the reason for this post, the saying of Lewis Newton Wood's that struck my funny bone. It's taken from Gilbert Cope's Genealogy of the Sharpless Family Descended from John and Jane Sharples, Settlers Near Chester, Pennsylvania, 1682.

All my progenitors were Baptists of the Orthodox belief, i.e. Calvinists; and that is my own religious belief, except with the Calvinism pretty much left out.

Which may explain why this Baptist's funeral was held in a Methodist church. I know, it actually makes sense when you dig into the history of the Baptist Church, but still....

I like an ancestor with a sense of humor.