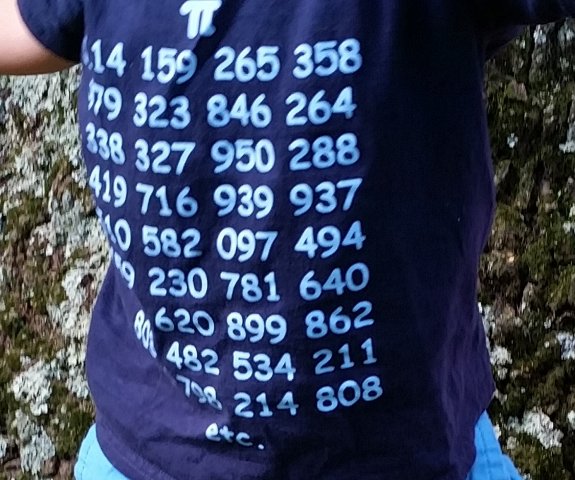

This photo is from 2014. I think it's still Joseph's favorite shirt. I bought him another, in a larger size, because he kept wearing this one even though he'd worn it out and outgrown it.

Fun Fact: Albert Einstein was born on Pi Day.

Permalink | Read 1777 times | Comments (1)

Category Just for Fun: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

Hezekiah Scovil Porter WW I Diary Transcription continued

The following is the next installment of the transcription of Hezekiah Scovil Porter’s diary of his time in the army until his death at Chateau Thierry on July 22, 1918. Again there is one from the beginning of the book and one from 100 years ago today.

Original is in black, annotations in red, horizontal lines indicate page breaks.

(France)

Tuesday Nov 13th

Cards this A.M. hike after wood this P.M.

(France)

Wednesday Mar. 13th

Some gas + a few shells this A.M. Off guard at 4:30 P.M. Out at 7:00 – find (sic) until 9:30. On gun guard at 1:30 – off at 7:00 A.M.

Previous posts: Introduction, Part 1, Part 2, Part 3, Part 4, Part 5, Part 6, Part 7, Part 8, Part 9, Part 10, Part 11, Part 12, Part 13, Part 14, Part 15, Part 16, Part 17, Part 18, Part 19, Part 20, Part 21, Part 22, Part 23, Part 24, Part 25, Part 26, Part 27, Part 28, Part 29, Part 30, Part 31, Part 32

Permalink | Read 2217 times | Comments (0)

Category Porter's Turn: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

Hezekiah Scovil Porter WW I Diary Transcription continued

The following is the next installment of the transcription of Hezekiah Scovil Porter’s diary of his time in the army until his death at Chateau Thierry on July 22, 1918. Again there is one from the beginning of the book and one from 100 years ago today.

Original is in black, annotations in red, horizontal lines indicate page breaks.

(France)

Monday Nov 12th

Saw sun for 1st time since we’ve been here this A.M. Played cards. hike after wood.

(France)

Tuesday Mar. 12th

Gun guards at 1:30 A.M. off at 7:00 A.M. Gas guard at (12 overwritten 4 or 4 overwritten 12) 30 A.M.

Previous posts: Introduction, Part 1, Part 2, Part 3, Part 4, Part 5, Part 6, Part 7, Part 8, Part 9, Part 10, Part 11, Part 12, Part 13, Part 14, Part 15, Part 16, Part 17, Part 18, Part 19, Part 20, Part 21, Part 22, Part 23, Part 24, Part 25, Part 26, Part 27, Part 28, Part 29, Part 30, Part 31

Permalink | Read 2182 times | Comments (0)

Category Porter's Turn: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

I love Florida.

Though I spent the first 32 years of my life in the Northeast, I grew up vacationing every other year in Daytona Beach, where my grandparents lived a short walk from the "World's Most Famous Beach." It was wonderful.

When we first considered moving here, however, I was hesitant, full of the anti-Southern prejudice that is the sea in which Northeasterners swim. Not that Florida is Deep South—we have too many immigrants from every state and myriad countries for that—but it took me a few years not to automatically associate a southern accent with ignorance and prejudice. But life has a way of bringing humility, and now I treasure the Sunshine State and its people, defending them ardently against those (northern) folks who say our state is crazy.

Now I wonder if they were right all along. This week, Florida did a crazy thing.

Crazier even than the state constitutional amendment mandating correct treatment of pot-bellied pigs. (Not necessarily a bad idea in itself, but very bad as a change to the Constitution.)

Our legislators voted to remain on Daylight Saving Time all year. Thank goodness, it requires an Act of Congress to put that into effect, but Congress has shown it is not immune to Crazy, and Florida legislators have now trumpeted their madness to the world. Overwhelmingly. Democrats and Republicans. Bipartisan lunacy.

They hope to start a movement that other states will follow and force Congress to act in their favor.

Florida has just fired the first shot in a Civil War reenactment, from the Yankee side.

I completely understand why people living in the North like Daylight Saving Time. Living for 18 months in Boston, much further north than Orlando and on the eastern edge of the time zone to boot, made me realize why New Englanders appreciate the time change, in both directions. But here in Florida, much closer to the equator, our seasons are more nearly constant, and changing the clocks is more annoying than useful.

If America were to stay on Standard Time all year, I would like that. Let noon be the time when the sun is highest overhead (or as close as time zones will allow) and be done with it. But to stay on Summer Time year 'round? Let's not mock Mother Nature more than we must.

I always admired—though never emulated—our daughter's steadfast determination not to change her clocks away from "real time" but make in her head the necessary adjustment to the crazy world. But if the Florida legislature had voted to stay on Standard Time year 'round, I would still oppose it, unless the rest of the country followed suit. Aren't we divided too much already, without having to suffer a time change while crossing the Florida-Georgia border?

I wouldn't blame the Bostonians if they objected to year-'round Standard Time. I'd prefer it myself, but will put up with the semi-annual changes for their sake. But Daylight Time forever? Never! I'm frustrated enough that they have extended the weeks of DST, putting us out of sync with Europe.

And even in Boston, do we really need DST any more? We fool ourselves with idyllic pictures of children in their backyards, kicking around a ball in the extra hour of evening sun. But is that how most of us improve that shining hour? Aren't we, and our children, much more likely to be inside staring at a screen?

In any case, if we go on DST and never return, we will have permanently lost an hour of life. Today I grudgingly suffered a 23-hour day, filled with the hope of receiving a 25-hour day in the fall. I want my hour back!

Permalink | Read 1707 times | Comments (2)

Category Random Musings: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

Hezekiah Scovil Porter WW I Diary Transcription continued

The following is the next installment of the transcription of Hezekiah Scovil Porter’s diary of his time in the army until his death at Chateau Thierry on July 22, 1918. Again there is one from the beginning of the book and one from 100 years ago today.

Original is in black, annotations in red, horizontal lines indicate page breaks.

(France)

Sunday Nov. 11th

Cold. Nothing doing. Can’t go out around anywhere. Turned in early tonight.

(France)

Monday Mar. 11th

Up again at 4:45 A.M. to stand to. Breakfast + to bed. Gun guard + digging at 11:30 A.M. Relieved at 4:30 P.M. Not much excitement.

Previous posts: Introduction, Part 1, Part 2, Part 3, Part 4, Part 5, Part 6, Part 7, Part 8, Part 9, Part 10, Part 11, Part 12, Part 13, Part 14, Part 15, Part 16, Part 17, Part 18, Part 19, Part 20, Part 21, Part 22, Part 23, Part 24, Part 25, Part 26, Part 27, Part 28, Part 29, Part 30

Permalink | Read 2170 times | Comments (0)

Category Porter's Turn: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

Hezekiah Scovil Porter WW I Diary Transcription continued

The following is the next installment of the transcription of Hezekiah Scovil Porter’s diary of his time in the army until his death at Chateau Thierry on July 22, 1918. Again there is one from the beginning of the book and one from 100 years ago today.

Original is in black, annotations in red, horizontal lines indicate page breaks.

(France)

Saturday Nov. 10th

Rain hard this A.M. No calls. Went on guard this P.M. at 1:30. On 1st relief 1:30 to 5:30. Quite comfortable in guard house by fire. Got feet warm + dry for 1st time in about a week. One fellow came down with measles tonight + all in our barracks

are quarantined.

(France)

Sunday Mar. 10th

Packing + cleaning up. Getting ready to go to trenches again. Company left this P.M. Drove up one car, came back with some “C” men. Was driven back again. Meantime guns set up. On gun guard soon as back. Quietly off at 12:30 A.M. Up again at 4:45 A.M. to stand to.

Previous posts: Introduction, Part 1, Part 2, Part 3, Part 4, Part 5, Part 6, Part 7, Part 8, Part 9, Part 10, Part 11, Part 12, Part 13, Part 14, Part 15, Part 16, Part 17, Part 18, Part 19, Part 20, Part 21, Part 22, Part 23, Part 24, Part 25, Part 26, Part 27, Part 28, Part 29

Permalink | Read 2381 times | Comments (0)

Category Porter's Turn: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

Hezekiah Scovil Porter WW I Diary Transcription continued

The following is the next installment of the transcription of Hezekiah Scovil Porter’s diary of his time in the army until his death at Chateau Thierry on July 22, 1918. Again there is one from the beginning of the book and one from 100 years ago today.

Original is in black, annotations in red, horizontal lines indicate page breaks.

(France)

Friday Nov. 9th

Hiked over to a town this. Raining + got soaked. Raining too hard for doing anything this P.M.

(France)

Saturday Mar 9th.

Calisthenics this A.M. General clean up. Inspection this P.M.

Previous posts: Introduction, Part 1, Part 2, Part 3, Part 4, Part 5, Part 6, Part 7, Part 8, Part 9, Part 10, Part 11, Part 12, Part 13, Part 14, Part 15, Part 16, Part 17, Part 18, Part 19, Part 20, Part 21, Part 22, Part 23, Part 24, Part 25, Part 26, Part 27, Part 28

Permalink | Read 2189 times | Comments (0)

Category Porter's Turn: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

Ember Rising, the latest in S. D. Smith's Green Ember series, is now available! I have just completed a delicious re-read of all the previous books—The Green Ember, The Black Star of Kingston, Ember Falls, and The Last Archer—and am almost halfway through my advance copy of Ember Rising. It was hard to wait patiently to read the new book, but worthwhile to get the old stories clear in my head again. (I am not like J. R. R. Tolkien, for whom there was only one "first reading" of a book. I read voraciously, and I read fast—but I forget quickly, too, and don't really remember a book until I've read it several times.)

So, any of you Green Ember fans who didn't get advance copies, now's your chance! Here's the link at S. D. Smith's store, and here's Amazon's.

Hezekiah Scovil Porter WW I Diary Transcription continued

The following is the next installment of the transcription of Hezekiah Scovil Porter’s diary of his time in the army until his death at Chateau Thierry on July 22, 1918. Again there is one from the beginning of the book and one from 100 years ago today.

Original is in black, annotations in red, horizontal lines indicate page breaks.

(France)

Thursday Nov. 8th

Raining. Went after wood up in woods after wood this A.M. Went again this P.M. Tried to clean off some of mud on mess strut this P.M. Stoves installed in our barracks this P.M.

(France)

Friday Mar. 8th

Warm + like spring. Drill this A.M. Played ball + quakes this P.M. (Quakes may be a form of craps.)

Previous posts: Introduction, Part 1, Part 2, Part 3, Part 4, Part 5, Part 6, Part 7, Part 8, Part 9, Part 10, Part 11, Part 12, Part 13, Part 14, Part 15, Part 16, Part 17, Part 18, Part 19, Part 20, Part 21, Part 22, Part 23, Part 24, Part 25, Part 26, Part 27

Permalink | Read 2171 times | Comments (0)

Category Porter's Turn: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

Hezekiah Scovil Porter WW I Diary Transcription continued

The following is the next installment of the transcription of Hezekiah Scovil Porter’s diary of his time in the army until his death at Chateau Thierry on July 22, 1918. Again there is one from the beginning of the book and one from 100 years ago today.

Original is in black, annotations in red, horizontal lines indicate page breaks.

(France)

Wednesday Nov 7th

Laid up today with bum feet. Didn’t

do anything much.

(France)

Thursday Mar 7th

Fine day. Drill this A.M. Hike this P.M.

Previous posts: Introduction, Part 1, Part 2, Part 3, Part 4, Part 5, Part 6, Part 7, Part 8, Part 9, Part 10, Part 11, Part 12, Part 13, Part 14, Part 15, Part 16, Part 17, Part 18, Part 19, Part 20, Part 21, Part 22, Part 23, Part 24, Part 25, Part 26

Permalink | Read 2254 times | Comments (0)

Category Porter's Turn: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

Hezekiah Scovil Porter WW I Diary Transcription continued

The following is the next installment of the transcription of Hezekiah Scovil Porter’s diary of his time in the army until his death at Chateau Thierry on July 22, 1918. Again there is one from the beginning of the book and one from 100 years ago today.

Original is in black, annotations in red, horizontal lines indicate page breaks.

(France)

Tuesday Nov 6th.

Walked to town this A.M. All got steel helmets. Back late. Dinner late. Hungry. Little talk by Hartford pastor this P.M. then hiked to woods for firewood. Tired + sore feet tonight.

(France)

Wednesday Mar. 6th

Fine day – warm

Off guard at 1:30

Previous posts: Introduction, Part 1, Part 2, Part 3, Part 4, Part 5, Part 6, Part 7, Part 8, Part 9, Part 10, Part 11, Part 12, Part 13, Part 14, Part 15, Part 16, Part 17, Part 18, Part 19, Part 20, Part 21, Part 22, Part 23, Part 24, Part 25

Permalink | Read 2242 times | Comments (0)

Category Porter's Turn: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

Hezekiah Scovil Porter WW I Diary Transcription continued

The following is the next installment of the transcription of Hezekiah Scovil Porter’s diary of his time in the army until his death at Chateau Thierry on July 22, 1918. Again there is one from the beginning of the book and one from 100 years ago today.

Original is in black, annotations in red, horizontal lines indicate page breaks.

(France)

Monday Nov. 5th

Up early. Went on about 6 mile hike this A.M. Sitting up exercises afterward then double time back to camp. Drill this P.M. then another hike mostly up hill. Letter from Polly this evening. (Polly was his sister.)

(France)

Tuesday Mar. 5th

Drill this A.M. On guard at 1:30.

Previous posts: Introduction, Part 1, Part 2, Part 3, Part 4, Part 5, Part 6, Part 7, Part 8, Part 9, Part 10, Part 11, Part 12, Part 13, Part 14, Part 15, Part 16, Part 17, Part 18, Part 19, Part 20, Part 21, Part 22, Part 23, Part 24

Permalink | Read 2181 times | Comments (0)

Category Porter's Turn: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

Hezekiah Scovil Porter WW I Diary Transcription continued

The following is the next installment of the transcription of Hezekiah Scovil Porter’s diary of his time in the army until his death at Chateau Thierry on July 22, 1918. Again there is one from the beginning of the book and one from 100 years ago today.

Original is in black, annotations in red, horizontal lines indicate page breaks.

(France)

Sunday Nov. 4th

Went for short hike this A.M. Filled beds with straw. Nothing much doing.

(France)

Monday Mar. 4th

Drill this A.M. Snow. Short hike this P.M.

Previous posts: Introduction, Part 1, Part 2, Part 3, Part 4, Part 5, Part 6, Part 7, Part 8, Part 9, Part 10, Part 11, Part 12, Part 13, Part 14, Part 15, Part 16, Part 17, Part 18, Part 19, Part 20, Part 21, Part 22, Part 23

Permalink | Read 2180 times | Comments (0)

Category Porter's Turn: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

Hezekiah Scovil Porter WW I Diary Transcription continued

The following is the next installment of the transcription of Hezekiah Scovil Porter’s diary of his time in the army until his death at Chateau Thierry on July 22, 1918. Again there is one from the beginning of the book and one from 100 years ago today.

Original is in black, annotations in red, horizontal lines indicate page breaks.

(France)

Sat. Nov. 3rd

Up late. Had good sleep. Breakfast at 9. Nothing doing all day.

(France)

Sunday March 3rd

Punk day – nothing doing.

Previous posts: Introduction, Part 1, Part 2, Part 3, Part 4, Part 5, Part 6, Part 7, Part 8, Part 9, Part 10, Part 11, Part 12, Part 13, Part 14, Part 15, Part 16, Part 17, Part 18, Part 19, Part 20, Part 21, Part 22

Permalink | Read 2231 times | Comments (0)

Category Porter's Turn: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

Hezekiah Scovil Porter WW I Diary Transcription continued

The following is the next installment of the transcription of Hezekiah Scovil Porter’s diary of his time in the army until his death at Chateau Thierry on July 22, 1918. Again there is one from the beginning of the book and one from 100 years ago today.

Original is in black, annotations in red, horizontal lines indicate page breaks.

(France)

Friday Nov. 2nd

Arrived In Neuf Chateau (sic) about 9 A.M. Hiked over to Mont Neuf Chateau this A.M. Other American troops. Saw lots of them on way today. Put in small new Barracks with headquarters. Pretty good quarters.

(France)

Saturday March 2nd

Snowing + blowing + cold. Short drill this A.M. Nothing doing this P.M.

Previous posts: Introduction, Part 1, Part 2, Part 3, Part 4, Part 5, Part 6, Part 7, Part 8, Part 9, Part 10, Part 11, Part 12, Part 13, Part 14, Part 15, Part 16, Part 17, Part 18, Part 19, Part 20, Part 21

Permalink | Read 2228 times | Comments (0)

Category Porter's Turn: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]