In 2025 I read 35 books, among my lowest annual totals and less than half 2024's count. I know of no particular reason for that, unless it is that six of the books were by Brandon Sanderson; dropping one of his books on your foot could send you to the emergency room. But some years are just like that: You get extra busy, other things take higher priority, there's a different mix of easy reading and that which takes more time and effort. I am content, although I do hope to read more in 2026.

The statistics:

- Books read this year: 35 (average 2.9 per month)

- Total books read since 2010: 1067

- Total unique books (not counting multiple readings since 2010): 914

- Fiction: 26 (74%)

- Non-fiction: 8 (23%)

- Other: 1 (3%)

- Months with most books: September (7)

- Month with fewest books: February, March, and April tied (1)

- Authors read most frequently: Laura Ingalls Wilder (9), Brandon Sanderson (6), J. R. R. Tolkien (4), S. D. Smith (3)

Here's the list, sorted by title. The ratings (★) and warnings (☢) are on a scale from 1 to 5, with 1 being the lowest/mildest. Warnings, like the ratings, are highly subjective and reflect context, perceived intended audience, and my own biases. They may be for sexual content, language, violence, worldview, or anything else that I find objectionable. Nor are they completely consistent; your mileage may vary.

| Title | Author | Category | Rating/Warning | Notes |

| Antipode | Heather Heying | non-fiction | ★★★★ | |

| The Bible: New Testament | King James Version | non-fiction | ★★★★★ | |

| The Bible: New Testament | New International Version, modern edition | non-fiction | ★★★★★ | Almost unbearable due to stilted PC language and frequent use of "they" as singular. |

| The Bible: Old Testament | New International Version, modern edition | non-fiction | ★★★★★ | In the 1970's this was an excellent translation, but its modern form is like fingernails on a blackboard with its avoidance of gendered pronouns. |

| The Bible: Psalms | New Living Translation | non-fiction | ★★★★★ | Somewhat interesting but awkward, feels slangy and inaccurate. It was kind of fun, and not necessarily easy, trying to map these psalms with the psalms that I know. Also, the avoidance of words like "mankind" is annoying. |

| Citizen of the Galaxy | Robert Heinlein | fiction | ★★★★ | |

| Facing the Beast | Naomi Wolf | non-fiction | ★★★★ | |

| The Green Ember Lost Tales: The Lost Key | S. D. Smith | fiction | ★★★★ | |

| Haiku Origami and More | Judith Newton and Mayumi Tabuchi | non-fiction | ★★ | |

| Helmer In the Dragon Tomb | S. D. Smith | fiction | ★★★★★ | |

| Helmer In the Dragon Tomb | S. D. Smith | fiction | ★★★★★ | Read twice this year |

| Hidden Figures | Margot Lee Shetterly | non-fiction | ★★★★★ | Even better than the movie, with much more information |

| Little House 1: Little House in the Big Woods | Laura Ingalls Wilder | fiction | ★★★★★ | |

| Little House 2: Farmer Boy | Laura Ingalls Wilder | fiction | ★★★★★ | |

| Little House 3: Little House on the Prairie | Laura Ingalls Wilder | fiction | ★★★★★ | |

| Little House 4: On the Banks of Plum Creek | Laura Ingalls Wilder | fiction | ★★★★★ | |

| Little House 5: By the Shores of Silver Lake | Laura Ingalls Wilder | fiction | ★★★★ | |

| Little House 6: The Long Winter | Laura Ingalls Wilder | fiction | ★★★★★ | |

| Little House 7: Little Town on the Prairie | Laura Ingalls Wilder | fiction | ★★★ | Includes an insensitive but culturally appropriate minstrel show |

| Little House 8: These Happy Golden Years | Laura Ingalls Wilder | fiction | ★★★ | |

| Little House 9: The First Four Years | Laura Ingalls Wilder | fiction | ★★★ | |

| The Lord of the Rings 1: The Fellowship of the Ring | J. R. R. Tolkien | fiction | ★★★★★ | |

| The Lord of the Rings 2: The Two Towers | J. R. R. Tolkien | fiction | ★★★★★ | |

| The Lord of the Rings 3: The Return of the King | J. R. R. Tolkien | fiction | ★★★★★ | |

| Percy Jackson and the Olympians 3:The Titan's Curse | Rick Riordan | fiction | ★★★★ | |

| Podkayne of Mars | Robert Heinlein | fiction | ★★★★ | |

| The Stone Soldier and the Lady | Blair Bancroft (Grace Kone) | fiction | ★★★ ☢ | |

| Stormlight 0: Warbreaker | Brandon Sanderson | fiction | ★★★★★ ☢ | Much better on the second reading. The sex scenes themselves are minimal and chaste, but some are more arousing than I appreciate. As usual, it is quite violent. But it's a great story, and although it was published in 2009, the idea of hidden forces pushing people towards war and the deliberate incitement to fear and hate seem prescient in 2025. |

| Stormlight 1: The Way of Kings | Brandon Sanderson | fiction | ★★★★ ☢ | Gripping, thought-provoking, too violent. Earned another star on second reading. |

| Stormlight 2: Words of Radiance | Brandon Sanderson | fiction | ★★★★ ☢ | Gripping, thought-provoking, too violent; again, better on second reading |

| Stormlight 3: Oathbringer | Brandon Sanderson | fiction | ★★★★★ ☢ | Probably my favorite of the series. |

| Stormlight 4: Rhythm of War | Brandon Sanderson | fiction | ★★★ ☢ | This took me till more than 40% through to get more than mildly interested. Too many battle scenes, and those scenes too long. Also, too much modern pop psychology that I already get too much of on Facebook. But the second half of the book had me hooked. The ending is somewhat unsatisfactory. |

| Stormlight 5: Wind and Truth | Brandon Sanderson | fiction | ★★★★ ☢ | Much better than #4. Still too much psychology, too much violence. But still a remarkable book and series. |

| Tales from the Perilous Realm | J. R. R. Tolkien | other | ★★★★★ | Some fiction, some non-fiction. Contains "Leaf by Niggle," my favorite of Tolkien's short stories. |

| Team Burger Shed | Tavin Dillard | fiction | ★★★ | Starts slow, but ends well; better if you picture it being a stand-up comedy routine rather than a book. |

We have so many wonderful Christmas albums, collected for well over half a century, many wonderful, wonderful works reaching from the 21st century back to almost as long as Christmas music has existed.

But the one that most strongly and emotionally says Christmas to me is the Harry Simeone Chorale album, "Sing We Now of Christmas." It was released in 1959 and is my earliest memory of Christmas music. To my great joy, I recently found the album available on YouTube. The cover is a little confusing, because it shows the title as "The Little Drummer Boy," and the image is different. But the songs are the same. This link, Sing We Now of Christmas, will take you to a playlist where you can hear the whole album in order, or return and play your favorites.

I realize that my love of this recording of Christmas songs is wrapped up in the aura of a very happy childhood and all that I loved about the Christmas season, so your mileage may vary. But, as objectively as I can manage, I maintain it's one of the best compilations for telling the story of Christmas coherently through song while including both the old familiar carols and lesser-known songs from more distant times and places.

Although I read all of the original Harry Potter books when they first came out, I saw only a few of the films. Thanks to a friend's gift, however, we've recently been watching the early ones, and I was able to enjoy them thoroughly because it's been so long since I read the books that I can't whine about the differences.

A few days ago we viewed Goblet of Fire for the first time. You can imagine the powerful impact of the following scene. I knew I had to find it online and share it here.

Permalink | Read 1108 times | Comments (0)

Category Reviews: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Politics: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Everyday Life: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Inspiration: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Here I Stand: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Heroes: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

Tom Lehrer didn't quite make it to his 100th birthday, and I'm sure he could have written a song about that.

I discovered him when I was in junior high school, and his album That Was the Year That Was is one of the few records I owned before marriage. I can't say as my parents approved of all of the songs—in retrospect I can see why—but they generally put up with my adolescent idiosyncracies.

Here's a great obituary for Lehrer from The Economist, cleverly interwoven with lines from his multitudinous satirical songs. You can read it for free, but you have to jump through a bunch of hoops that may or may not be worth the trouble. You need to enter, not just the usual name and e-mail address, but also your profession and industry. Worse, you have to fit your life into their limited boxes, which has never been easy for me. "Retired" and "Homemaker" are not options. On the other hand, writing homeschool reports has made me pretty good at stuffing whatever it was we were doing into conventional terminology.

His childhood had been a breeze of maths and music, with a preference for Broadway shows. He entered Harvard at 15 and graduated at 18, the sort of student who brought books of logical puzzles to dinner in hall, and, on the piano in his room, liked to play Rachmaninov with his left hand in one key and his right a semitone lower, making his friends grimace. He seemed bound for a glittering mathematical career, but then the songs erupted, written for friends but spreading by word of mouth, until he was famous. He wrote each one in a trice and performed, increasingly, in night clubs. By contrast his PhD, on the concept of the mode, vaguely occupied him for 15 years before he abandoned it.

Oh fame! Oh accolades! He had toured the world and packed out Carnegie Hall. Yes, they really panted to see a clean-cut Harvard graduate in horn-rimmed glasses pounding at a piano and singing: sometimes stern, sometimes morose, but often joyose, as he twisted in the knife. [Is that a typo for joyous, or a deliberate portmanteau of joyous and morose?]

When he suddenly stopped, and the output dropped, he was presumed dead. No, Tom Lehrer replied. Just having fun commuting between the coasts, teaching maths for a quarter of the year, ie the winter, at the University of California in sunny Santa Cruz, and spending the rest of the time in Cambridge, Massachusetts, being lazy. Never having to shovel snow; never having to see snow. And, being said to be dead, avoiding junk mail.

I wonder how he managed the last. We're still getting junk mail for Porter's father, who has been actually dead for six years.

Did he ever have hopes of extending the frontier of scientific knowledge? Noooooo, unless you counted his Gilbert & Sullivan setting of the entire periodic table. He would rather retract it, if anything. He still taught maths, along with musical theatre, and that was his career. He had never wanted attention from people applauding his singing in the dark. His solitary, strictly private life made him happy; to fame he was indifferent. In 2020 he told everyone they could help themselves to his song rights. As for him, he returned to his puzzle books, as if he had never strayed.

Requiescat in pace, Tom Lehrer. Thanks for all the fun.

Many years ago, when Inspector Morse first aired on PBS, we watched several episodes, and have since enjoyed the whole series, plus the spin-offs Lewis (aka Inspector Lewis) and Endeavour. The stories, especially the more recent ones, often reflect objectionably "Hollywood" values, and there's a tinge of darkness that might not make them good fare for one who is already depressed. But it's hard to have police shows and murder mysteries without darkness, and the series are so very well crafted and acted that even the depressing parts are more like the spices that add depth and flavor to a stew.

And I love the music by composer Barrington Pheloung.

Here's the Morse theme:

The theme for Lewis (aka Inspector Lewis) I didn't find as moving as that for Morse and Endeavour, but it fits the show, which might be my favorite of the three due to Lewis' sidekick James Hathaway (played by Laurence Fox) and their interactions.

Endeavour brings back a variation on the original theme. I love those horns!

I've made no secret of the fact that I don't like the movie Forrest Gump. The era of the late 60's and early 70's was a really weird time for our country (and much of the Western world): uncomfortable, ugly, deranged, disagreeable, void of reason and sense. Quite a bit like the last decade or so, in fact. Watching Forrest Gump brought all that back, and I appreciated neither the reminder nor what I believe was an attempt to whitewash the times.

You'd think I'd have the same reaction to Pirates of Silicon Valley, which I watched recently, since it deals with some of the same era. But I enjoyed it thoroughly. Here's the description from Eric Hunley's Unstructured.

Pirates of Silicon Valley is a 1999 American biographical drama television film directed by Martyn Burke and starring Noah Wyle as Steve Jobs and Anthony Michael Hall as Bill Gates. Spanning the years 1971–1997 and based on Paul Freiberger and Michael Swaine's 1984 book Fire in the Valley: The Making of the Personal Computer, it explores the impact that the rivalry between Jobs (Apple Computer) and Gates (Microsoft) had on the development of the personal computer. The film premiered on TNT on June 20, 1999.

Two things made this a movie I would enjoy watching again. One is that it shows the good, the bad, and the ugly of that era without either oversensationalizing it or making excuses. The Promethean heroes who brought the power of computers to Everyman were severely flawed, but they were still heroes.

Even more than that, I loved the movie because it brought back good memories, especially at the beginning. The early days of computing were messy, but they were also exciting. I still remember sitting in a small room at the University of Rochester's Goler House, listening to Carl Helmers expounding on the wonders of the Apple 1 computer, which he demonstrated using a cassette tape as an input device. Porter and I looked at each other and said, "I want to buy stock in this company!" Unfortunately, Apple was not publicly traded then, and when it did go public, we were out of the loop and missed the IPO of $22/share and the chance to turn $1000 into $2.5 million. (My father did the same thing when he chose to buy our first house instead of investing the money in Haloid, as recommended by a friend who had just visited the company. Haloid later became Xerox.) We didn't get rich, but we did enjoy being on the fringes of the wild-and-woolly frontier.

Permalink | Read 1104 times | Comments (1)

Category Reviews: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Computing: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Glimpses of the Past: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Heroes: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

Thanks to the very valuable eReaderIQ, I learned that C. S. Lewis's The Screwtape Letters is currently on sale at Amazon for $0.00. You can't beat that price for excellent content, and it also includes Screwtape Proposes a Toast.

The Slight Edge: Turning Simple Disciplines into Massive Success and Happiness by Jeff Olson (Greenleaf Book Group, 2013)

The Slight Edge: Turning Simple Disciplines into Massive Success and Happiness by Jeff Olson (Greenleaf Book Group, 2013)

The trouble with having a very long "to read" list is that by the time I get around to reading a book, I'm likely to have forgotten who recommended it to me. That's the case with this one. But someone did, and I recently read it.

The Slight Edge is not a book I would necessarily have picked up on my own, especially not after having flipped through it. It has the feel of one of those self-help books that spend a lot of words reiterating things we already know. And really, it could have been a lot shorter; in this, it has the defects of a Presbyterian sermon, only worse.

And yet, it was Martin Luther, I believe, who when asked, "Why do you preach on justification by faith every week?" replied, "Because you forget it every week." Sometimes we need to be reminded of what we already know. And sometimes the 40th repetition finally gets through.

Most of what Jeff Olson says here can be summarized by referring to the ancient story of the rice on the chessboard. You've heard it before: small actions (good or bad), repeated consistently and persistently over time, can result in huge gains (or losses) that can change your life dramatically.

What's the purpose of still another book telling us what we should already know? Is The Slight Edge worth reading for you? I have no idea. It's not great writing, and, as I said, repetitive. But I was able to read it for free thanks to our library, and found it worth the greater cost in time. Sometimes even those of us who don't have that many more squares on our chessboards need reminding of the simplest strategies.

Also, I found the second half much better than the first, as Olson expands his ideas further. I still wouldn't call it good writing, but there are a lot of good ideas there. Even if we've heard them a hundred times before. Martin Luther would understand.

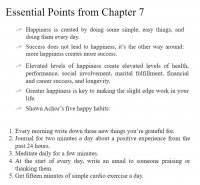

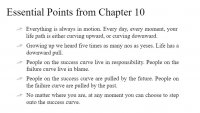

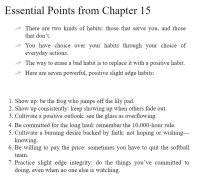

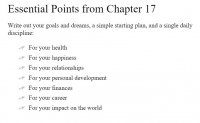

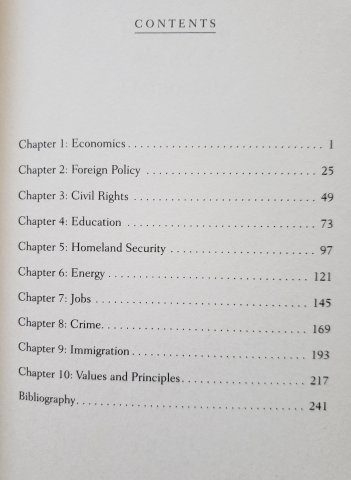

I'll reproduce each of the chapter summaries here. I don't know as they'll mean much to you if you haven't read the book, but they may give you a taste. And if you have read the book (like me) you may find them helpful reminders of what you learned (again). (Click on a page to enlarge it.)

King Arthur and His Knights of the Round Table by Roger Lancelyn Green (1953)

King Arthur and His Knights of the Round Table by Roger Lancelyn Green (1953)

The Adventures of Robin Hood by Roger Lancelyn Green (1956)

Roger Lancelyn Green's assembling and retelling of the stories of King Arthur and of Robin Hood makes me want to read his other collections of ancient tales (e.g. Egyptian, Greek, and Norse); he writes well and provides an excellent introduction to these classic stories. The only negative I would report about these particular editions is that the publisher apparently decided it would be a good idea to append a stomach-turning school-ish section. ("Can you see any similarities between Arthur and modern heroes such as Harry Potter or Luke Skywalker?") Somehow I don't think Green would have approved at all.

One thing I found delightful in both books was recognizing in Green's work echoes of the writing of C. S. Lewis and J. R. R. Tolkien. Not in the sense of copying or imitation, but that they all spring from the same roots.

Another is that these stories of chivalry and idealized behavior make it clear both that heroes are flawed people, and that they are nonetheless heroes.

In the 1950's and early 1960's, when I was young, our hero stories were highly sanitized—and not just those for children. What mattered was the good that was done; negative events and characteristics were largely ignored. Fables are expected to be larger-than-life (think Paul Bunyan), but real people, no matter how amazing, should be, well, real people. It's important to know that God can do extraordinary things with ordinary people—being weak, fallen, broken, and/or stupid is no excuse for not doing the right thing.

Later decades turned the idealized hero narrative 180 degrees. It became de rigueur to take the people we admire and portray them not so much as flawed, but evil; to take delight in showing people at their worst, and pointing out that the good they did might have actually been harmful. This may have been a necessary corrective for a brief time, but it is the worse of the two errors.

Green does not hesitate to admit the flaws, errors, and sins of his characters, but lets their heroic actions shine. It's a good balance.

Citoyen de la Galaxie by Robert A. Heinlein (original publication 1957, this French edition 2011)

Citoyen de la Galaxie by Robert A. Heinlein (original publication 1957, this French edition 2011)

Back in August, I quoted a passage from Robert Heinlein's Citizen of the Galaxy. Inspired by this, and a good deal available for the Kindle version, I decided to reread it—in French.

It was a surprisingly delightful experience.

I had three years of mediocre French classes in high school, and have been working very casually, though consistently, with DuoLingo since I was a beta tester for them back in 2012. I have many frustrations with DuoLingo, but this week I discovered that it has actually given me a lot of French vocabulary and a pretty good feel for grammatical structures. I really enjoyed reading Citoyen de la Galaxie.

Naturally I didn't read it as quickly as the English version, but I surprised myself. My goal had been to work my way through ten pages per day. Instead, I was so caught up in the story that I finished it in just about a week.

It must be admitted that I was not a stranger to the story, which helped enormously. I first read Citizen of the Galaxy when I was in elementary school, and I've reread it several times since. How many times I have no idea, but I know that I last read it in 2017—before that, I don't know, except that it was earlier than 2010, when I began keeping track of the books I read. As I read the French, I was astonished to find the words of the English version coming back to me. Between that, the DuoLingo vocabulary, and occasional help from the Kindle French-English dictionary available at a touch, the reading was easy enough to keep me going.

I would not at all expect the same ease with an unfamiliar book. But the experience was exciting, especially since I would often find myself actually thinking in French for a few minutes after a session of reading.

I've learned to avoid food items labelled "no sugar added," because that usually does not mean the product is less sweet, but is artificially sweetened. When I picked up this bottle of ketchup, I expected to find sucralose, which I detest, in the ingredient list. I was surprised and pleased to see that the sweetener in this case was not sucralose, but rather stevia.

I've learned to avoid food items labelled "no sugar added," because that usually does not mean the product is less sweet, but is artificially sweetened. When I picked up this bottle of ketchup, I expected to find sucralose, which I detest, in the ingredient list. I was surprised and pleased to see that the sweetener in this case was not sucralose, but rather stevia.

Ingredients: tomato concentrate from red ripe tomatoes, distilled white vinegar, salt, natural flavoring, stevia leaf extract, onion powder.

I had to laugh at the claim "Sweetness from PLANTS" on the label. Just what do they think sugar cane is, an animal?

But I got over it, and decided to try a bottle.

Much to my surprise, I loved it at first taste, and have so far had no cause to change my mind. It doesn't taste artificial, and has a brighter, fresher taste than regular ketchup. Time will tell, but I may be a convert.

The Firing Squad

The Firing Squad

The first thing I must say about this movie is that it did everything I asked of it, and did it well.

The temperature and humidity were as bad as anything Florida had to offer, and promised to get worse in the afternoon. The place we were staying in Connecticut has no air conditioning, and the breeze that usually makes hot temperatures bearable if not actually pleasant was not doing well, and promised to be nonexistent at low tide.

One of the first places Willis Carrier introduce his miraculous invention was the movie theatres, to which people flocked for relief from hot city summers. We followed suit, choosing to watch The Firing Squad because we were under the erroneous impression that it was produced by the same folks as the wonderful and moving Sound of Freedom. I wish it had been, because the true story it tells, which made the news all over Asia, never seemed to make any headway here in the West.

It's a powerful, true story that deserves a better movie.

I don't properly appreciate great production values until I see a movie where they're lacking. The story is great, but I confess to cringing through much (though not all) of the movie. There were just too many things that didn't ring true. One of the least important yet most annoying to me was this: How can you have a movie, set in an Indonesian prison, with heat and rain and mud and work details, and whatever inhumane conditions one might expect in such a place—and the prisoners' bright orange uniforms remain clean and pressed throughout? Trivial, perhaps, but it sure struck a discordant note.

Speaking of notes, I did appreciate that when the men were singing Amazing Grace in the chapel service, some of them were off pitch. Now that was realistic.

I also wish the reformed characters showed in the movie some grief and repentence for their heinous crimes. I'll bet the real men did.

Great story, mediocre movie. Only you can decide if you'll put up with the latter for the former. And I must say that movies made outside of the high-budget, Hollywood world are getting better, and that's something. Here's an interview with two of the actors that you might find interesting.

But as I said, The Firing Squad did exactly what I asked of it, providing us with two hours of cool, dry comfort. Definitely worth the price of admission. I suppose we could have gone to the grocery store instead, which was also air conditioned—but that would have cost a whole lot more.

12 Rules for Life: An Antidote to Chaos by Jordan Peterson (2018)

12 Rules for Life: An Antidote to Chaos by Jordan Peterson (2018)

Beyond Order: 12 More Rules for Life by Jordan Peterson (2021)

I can't remember where I first encountered Jordan Peterson; the odds are that I heard him mentioned in a DarkHorse podcast, but that's guessing. Whatever it was, I was intrigued enough to watch his three-hour Lex Fridman interview (not all at once!). Which then led me to 12 Rules for Life.

I'm not sure how to express how I feel about that book. I've since seen several videos of Peterson speaking, and that is my favorite way to learn from him. If you know me, you know how extraordinary that is. I almost always prefer the written word to the spoken, and find videos a frustrating medium to deal with. I guess there are always exceptions!

Both 12 Rules for Life, and its sequel, Beyond Order, are worth reading. In many ways, Peterson makes a lot of sense. I'm guessing that growing up in the rough backwoods of Alberta; working in multiple fields of endeavor, from harsh physical labor to clinical psychology to university professor to popular lecturer; enduring intense physical suffering, in himself and his family; and dealing with "cancel culture" first-hand and very publicly for his opinions—I'm guessing that that gives you experiences worth talking about.

Peterson also sees more clearly than most of us, and what he says is full of wisdom. I disagree strongly with some of his ideas, but so much is spot-on he's definitely worth paying attention to.

My problem is that I could never wrap my head around psychology or philosophy, which is probably why I never found them interesting. (No doubt the reverse is also true.) Peterson's books are part good, practical advice (which I love), and part what I see as strange philosophcal and psychological theories (which I don't). When I shared 12 Rules for Life with my then-teenaged grandson, he thought it was one of the best books ever. Then again, he's a deep thinker and seems to have a talent for philosophy. At least more than I do, which, admittedly, is a low bar.

For all that I'm ambivalent about the books (though not about Peterson himself), I believe this quotations section is longer than for any other review I've written. I made a few comments within it, but not many. I have no illusions that anyone (except perhaps the aforementioned grandson) will read them all, though many of you may skim through them. I'm putting them out here for the few who will appreciate them, and so that I will have my favorite quotes collected together where I can refer to (and search for) them. I've divided them into the two books, and within each by chapters. I've highlighted the chapter headings, which are the "rules," so you can scroll through the pages and catch all the rules if you wish to.

Excerpts from 12 Rules for Life

Forward by Norman Doidge

[Jordan] alerted his students to topics rarely discussed in university, such as the simple fact that all the ancients, from Buddha to the biblical authors, knew what every slightly worn-out adult knows, that life is suffering.

Scccccratccch the most clever postmodern-relativist professor’s Mercedes with a key, and you will see how fast the mask of relativism (with its pretense that there can be neither right nor wrong) and the cloak of radical tolerance come off.

The foremost rule is that you must take responsibility for your own life. Period.

Overture (introduction)

In the West, we have been withdrawing from our tradition-, religion- and even nation-centered cultures, partly to decrease the danger of group conflict. But we are increasingly falling prey to the desperation of meaninglessness, and that is no improvement at all.

Rule 1: Stand up straight with your shoulders back

Order can become excessive, and that’s not good, but chaos can swamp us, so we drown—and that is also not good. We need to stay on the straight and narrow path. Each of the twelve rules of this book—and their accompanying essays—therefore provide a guide to being there. “There” is the dividing line between order and chaos. That’s where we are simultaneously stable enough, exploring enough, transforming enough, repairing enough, and cooperating enough. It’s there we find the meaning that justifies life and its inevitable suffering.

Mark Twain once said, “It’s not what we don’t know that gets us in trouble. It’s what we know for sure that just ain’t so.”

If Mother Nature wasn’t so hell-bent on our destruction, it would be easier for us to exist in simple harmony with her dictates.

The body, with its various parts, needs to function like a well-rehearsed orchestra. Every system must play its role properly, and at exactly the right time, or noise and chaos ensue. It is for this reason that routine is so necessary. The acts of life we repeat every day need to be automatized. They must be turned into stable and reliable habits, so they lose their complexity and gain predictability and simplicity.

Anxiety and depression cannot be easily treated if the sufferer has unpredictable daily routines.

If you can bite, you generally don’t have to. ... The forces of tyranny expand inexorably to fill the space made available for their existence. People who refuse to muster appropriately self-protective territorial responses are laid open to exploitation as much as those who genuinely can’t stand up for their own rights because of a more essential inability or a true imbalance in power.

When once-naïve people recognize in themselves the seeds of evil and monstrosity, and see themselves as dangerous (at least potentially)—their fear decreases. They develop more self-respect. Then, perhaps, they begin to resist oppression. They see that they have the ability to withstand, because they are terrible too. They see they can and must stand up, because they begin to understand how genuinely monstrous they will become, otherwise, feeding on their resentment, transforming it into the most destructive of wishes. To say it again: There is very little difference between the capacity for mayhem and destruction, integrated, and strength of character.

Circumstances change, and so can you. Positive feedback loops, adding effect to effect, can spiral counterproductively in a negative direction, but can also work to get you ahead.

If you present yourself as defeated, then people will react to you as if you are losing. If you start to straighten up, then people will look at and treat you differently.

Rule 2: Treat yourself like someone you are responsible for helping

... the traditional insistence on the androgyny of Christ.

No. Just no. Maybe some tradition, somewhere—the world abounds in heresies, some more bizarre than others. Certainly, in the Incarnation, Jesus took upon himself all of humanity, male and female. But if he had been anything other than physically and psychologically male, he would not have commanded the respect that he obviously did. This is just weird.

You can’t just be stable, and secure, and unchanging, because there are still vital and important new things to be learned.

It is far better to render Beings in your care competent than to protect them.

Only man will inflict suffering for the sake of suffering. That is the best definition of evil I have been able to formulate. Animals can’t manage that, but humans, with their excruciating, semi-divine capacities, most certainly can.

There are so many ways that things can fall apart, or fail to work altogether, and it is always wounded people who are holding it together.

It would be good to make the world a better place. Heaven, after all, will not arrive of its own accord. We will have to work to bring it about, and strengthen ourselves, so that we can withstand the deadly angels and flaming sword of judgment that God used to bar its entrance.

This is one of several areas where I disagree with Peterson, since I believe strongly that heaven is not something achievable by people "working to bring it about." Nonetheless, we agree that it is right to work as best we can in that direction.

Rule 3: Make friends with people who want the best for you

Sometimes, when people have a low opinion of their own worth—or, perhaps, when they refuse responsibility for their lives—they choose a new acquaintance, of precisely the type who proved troublesome in the past. ... People choose friends who aren’t good for them for other reasons, too. Sometimes it’s because they want to rescue someone. This is more typical of young people, although the impetus still exists among older folks who are too agreeable or have remained naïve or who are willfully blind. Someone might object, “It is only right to see the best in people. The highest virtue is the desire to help.” But not everyone who is failing is a victim, and not everyone at the bottom wishes to rise, although many do, and many manage it. Nonetheless, people will often accept or even amplify their own suffering, as well as that of others, if they can brandish it as evidence of the world’s injustice.

Imagine someone not doing well. He needs help. He might even want it. But it is not easy to distinguish between someone truly wanting and needing help and someone who is merely exploiting a willing helper.

But Christ himself, you might object, befriended tax-collectors and prostitutes. How dare I cast aspersions on the motives of those who are trying to help? But Christ was the archetypal perfect man. And you’re you. How do you know that your attempts to pull someone up won’t instead bring them—or you—further down? Imagine the case of someone supervising an exceptional team of workers, all of them striving towards a collectively held goal; imagine them hardworking, brilliant, creative and unified. But the person supervising is also responsible for someone troubled, who is performing poorly, elsewhere. In a fit of inspiration, the well-meaning manager moves that problematic person into the midst of his stellar team, hoping to improve him by example. What happens?—and the psychological literature is clear on this point. Does the errant interloper immediately straighten up and fly right? No. Instead, the entire team degenerates. The newcomer remains cynical, arrogant and neurotic. He complains. He shirks. He misses important meetings. His low-quality work causes delays, and must be redone by others. He still gets paid, however, just like his teammates. The hard workers who surround him start to feel betrayed. “Why am I breaking myself into pieces striving to finish this project,” each thinks, “when my new team member never breaks a sweat?” The same thing happens when well-meaning counsellors place a delinquent teen among comparatively civilized peers. The delinquency spreads, not the stability. Down is a lot easier than up. (emphasis mine)

Before you help someone, you should find out why that person is in trouble. You shouldn’t merely assume that he or she is a noble victim of unjust circumstances and exploitation. It’s the most unlikely explanation, not the most probable. In my experience—clinical and otherwise—it’s just never been that simple. Besides, if you buy the story that everything terrible just happened on its own, with no personal responsibility on the part of the victim, you deny that person all agency in the past (and, by implication, in the present and future, as well). In this manner, you strip him or her of all power. (emphasis mine)

If you have a friend whose friendship you wouldn’t recommend to your sister, or your father, or your son, why would you have such a friend for yourself? You might say: out of loyalty. Well, loyalty is not identical to stupidity. Loyalty must be negotiated, fairly and honestly. Friendship is a reciprocal arrangement. You are not morally obliged to support someone who is making the world a worse place. Quite the opposite. You should choose people who want things to be better, not worse. It’s a good thing, not a selfish thing, to choose people who are good for you.

Rule 4: Compare youreslf to who you were yesterday, not to who someone else is today

It was easier for people to be good at something when more of us lived in small, rural communities. Someone could be homecoming queen. Someone else could be spelling-bee champ, math whiz or basketball star. There were only one or two mechanics and a couple of teachers. In each of their domains, these local heroes had the opportunity to enjoy the serotonin-fuelled confidence of the victor. It may be for that reason that people who were born in small towns are statistically overrepresented among the eminent. If you’re one in a million now, but originated in modern New York, there’s twenty of you—and most of us now live in cities. What’s more, we have become digitally connected to the entire seven billion. Our hierarchies of accomplishment are now dizzyingly vertical.

There is no shortage of tasteless artists, tuneless musicians, poisonous cooks, bureaucratically-personality-disordered middle managers, hack novelists and tedious, ideology-ridden professors. Things and people differ importantly in their qualities. Awful music torments listeners everywhere. Poorly designed buildings crumble in earthquakes. Substandard automobiles kill their drivers when they crash. Failure is the price we pay for standards and, because mediocrity has consequences both real and harsh, standards are necessary. We are not equal in ability or outcome, and never will be. A very small number of people produce very much of everything.

The infant is dependent on his parents for almost everything he needs. The child—the successful child—can leave his parents, at least temporarily, and make friends. He gives up a little of himself to do that, but gains much in return. The successful adolescent must take that process to its logical conclusion. He has to leave his parents and become like everyone else. He has to integrate with the group so he can transcend his childhood dependency. Once integrated, the successful adult then must learn how to be just the right amount different from everyone else. (emphasis mine)

I disagree with Peterson's insistance that the successful adolsecent must become like everyone else before he can learn how to be just the right amount different. Or, perhaps, it's just that our culture, with its heavy peer-orientation—continuously reinforced by school, advertisements, and the entertainment media—has dangerously twisted the process of socialization. Integrating into the society of their own age-mates is not what children need to grow into healthy adults; they need the society of good people of all ages, particularly those who have already established themselves as healthy members of society. Peer socialization is largely negative.

Called upon properly, the internal critic will suggest something to set in order, which you could set in order, which you would set in order—voluntarily, without resentment, even with pleasure. Ask yourself: is there one thing that exists in disarray in your life or your situation that you could, and would, set straight? Could you, and would you, fix that one thing that announces itself humbly in need of repair? Could you do it now?

What you aim at determines what you see.

That’s how you deal with the overwhelming complexity of the world: you ignore it, while you concentrate minutely on your private concerns. You see things that facilitate your movement forward, toward your desired goals. You detect obstacles, when they pop up in your path. You’re blind to everything else (and there’s a lot of everything else—so you’re very blind). And it has to be that way, because there is much more of the world than there is of you. You must shepherd your limited resources carefully. Seeing is very difficult, so you must choose what to see, and let the rest go.

Obedience is not enough. But it’s at least a start (and we have forgotten this): You cannot aim yourself at anything if you are completely undisciplined and untutored. ... That is not to say (to say it again) that obedience is sufficient. But a person capable of obedience—let’s say, instead, a properly disciplined person—is at least a well-forged tool.

Pay attention. Focus on your surroundings, physical and psychological. Notice something that bothers you, that concerns you, that will not let you be, which you could fix, that you would fix. You can find such somethings by asking yourself (as if you genuinely want to know) three questions: “What is it that is bothering me?” “Is that something I could fix?” and “Would I actually be willing to fix it?” If you find that the answer is “no,” to any or all of the questions, then look elsewhere. Aim lower. Search until you find something that bothers you, that you could fix, that you would fix, and then fix it. That might be enough for the day.

What if you instructed your wife, or your husband, to say “good job” after you fixed whatever you fixed? Would that motivate you? The people from whom you want thanks might not be very proficient in offering it, to begin with, but that shouldn’t stop you. People can learn, even if they are very unskilled at the beginning.

Attend to the day, but aim at the highest good.

Rule 5: Do not let your children do anything that makes you dislike them

Our society faces the increasing call to deconstruct its stabilizing traditions to include smaller and smaller numbers of people who do not or will not fit into the categories upon which even our perceptions are based. This is not a good thing.

Was it really a good thing, for example, to so dramatically liberalize the divorce laws in the 1960s? It’s not clear to me that the children whose lives were destabilized by the hypothetical freedom this attempt at liberation introduced would say so. Horror and terror lurk behind the walls provided so wisely by our ancestors. We tear them down at our peril. We skate, unconsciously, on thin ice, with deep, cold waters below, where unimaginable monsters lurk.

Hunter-gatherers, too, are much more murderous than their urban, industrialized counterparts, despite their communal lives and localized cultures. The yearly rate of homicide in the modern UK is about 1 per 100,000. It’s four to five times higher in the US, and about ninety times higher in Honduras, which has the highest rate recorded of any modern nation. But the evidence strongly suggests that human beings have become more peaceful, rather than less so, as time has progressed and societies became larger and more organized. The !Kung bushmen of Africa, romanticized in the 1950s by Elizabeth Marshall Thomas as “the harmless people,” had a yearly murder rate of 40 per 100,000, which declined by more than 30% once they became subject to state authority.

Pain is more potent than pleasure, and anxiety more than hope.

Children would not have such a lengthy period of natural development, prior to maturity, if their behaviour did not have to be shaped.

The fundamental moral question is not how to shelter children completely from misadventure and failure, so they never experience any fear or pain, but how to maximize their learning so that useful knowledge may be gained with minimal cost.

You can discipline your children, or you can turn that responsibility over to the harsh, uncaring judgmental world—and the motivation for the latter decision should never be confused with love.

If a society does not adequately reward productive, pro-social behavior, insists upon distributing resources in a markedly arbitrary and unfair manner, and allows for theft and exploitation, it will not remain conflict-free for long. If its hierarchies are based only (or even primarily) on power, instead of the competence necessary to get important and difficult things done, it will be prone to collapse, as well.

Disciplinary principle 1: limit the rules. Principle 2: use minimum necessary force. Here’s a third: parents should come in pairs. ... I am not saying we should be mean to single mothers, many of whom struggle impossibly and courageously—and a proportion of whom have had to escape, singly, from a brutal relationship—but that doesn’t mean we should pretend that all family forms are equally viable. They’re not. Period.

You love your kids, after all. If their actions make you dislike them, think what an effect they will have on other people, who care much less about them than you. Those other people will punish them, severely, by omission or commission. Don’t allow that to happen. Better to let your little monsters know what is desirable and what is not, so they become sophisticated denizens of the world outside the family.

A child who pays attention, instead of drifting, and can play, and does not whine, and is comical, but not annoying, and is trustworthy—that child will have friends wherever he goes. His teachers will like him, and so will his parents. If he attends politely to adults, he will be attended to, smiled at and happily instructed. He will thrive, in what can so easily be a cold, unforgiving and hostile world. Clear rules make for secure children and calm, rational parents.

Rule 6: Set your house in perfect order before you criticize the world

When the hurricane hit New Orleans, and the town sank under the waves, was that a natural disaster? The Dutch prepare their dikes for the worst storm in ten thousand years. Had New Orleans followed that example, no tragedy would have occurred. It’s not that no one knew. The Flood Control Act of 1965 mandated improvements in the levee system that held back Lake Pontchartrain. The system was to be completed by 1978. Forty years later, only 60 percent of the work had been done. Willful blindness and corruption took the city down. A hurricane is an act of God. But failure to prepare, when the necessity for preparation is well known—that’s sin.

Have you cleaned up your life? If the answer is no, here’s something to try: Start to stop doing what you know to be wrong. Start stopping today. ...

You can use your own standards of judgment. You can rely on yourself for guidance. You don’t have to adhere to some external, arbitrary code of behaviour (although you should not overlook the guidelines of your culture. Life is short, and you don’t have time to figure everything out on your own. The wisdom of the past was hard-earned, and your dead ancestors may have something useful to tell you).

Don’t blame capitalism, the radical left, or the iniquity of your enemies. Don’t reorganize the state until you have ordered your own experience. Have some humility. If you cannot bring peace to your household, how dare you try to rule a city?

Rule 7: Pursue what is meaningful (not what is expedient)

Benjamin Franklin once suggested that a newcomer to a neighbourhood ask a new neighbour to do him or her a favour, citing an old maxim: He that has once done you a kindness will be more ready to do you another than he whom you yourself have obliged.

What’s the difference between the successful and the unsuccessful? The successful sacrifice.

It is in fact nothing short of a miracle (and we should keep this fact firmly before our eyes) that the hierarchical slave-based societies of our ancestors reorganized themselves, under the sway of an ethical/religious revelation, such that the ownership and absolute domination of another person came to be viewed as wrong.

If there is something that is not good, then there is something that is good. If the worst sin is the torment of others, merely for the sake of the suffering produced—then the good is whatever is diametrically opposed to that. The good is whatever stops such things from happening.

To place the alleviation of unnecessary pain and suffering at the pinnacle of your hierarchy of value is to work to bring about the Kingdom of God on Earth.

Rule 8: Tell the truth—or at least don't lie

With love, encouragement, and character intact, a human being can be resilient beyond imagining.

All people serve their ambition. In that matter, there are no atheists. There are only people who know, and don’t know, what God they serve.

Things fall apart: this is one of the great discoveries of humanity. ... Without attention, culture degenerates and dies, and evil prevails.

Rule 9: Assume that the person you are listening to might know something you don't

The past appears fixed, but it’s not—not in an important psychological sense. There is an awful lot to the past, after all, and the way we organize it can be subject to drastic revision. ... A sufficiently happy ending can change the meaning of all the previous events. They can all be viewed as worthwhile, given that ending. ...

When you are remembering the past, as well, you remember some parts of it and forget others. You have clear memories of some things that happened, but not others, of potentially equal import—just as in the present you are aware of some aspects of your surroundings and unconscious of others. You categorize your experience, grouping some elements together, and separating them from the rest. There is a mysterious arbitrariness about all of this. You don’t form a comprehensive, objective record. You can’t.

The sexual abuse of children is distressingly common. However, it’s not as common as poorly trained psychotherapists think, and it also does not always produce terribly damaged adults.

The people I listen to need to talk, because that’s how people think. People need to think. ... People organize their brains with conversation.

A listening person tests your talking (and your thinking) without having to say anything. A listening person is a representative of common humanity. He stands for the crowd. Now the crowd is by no means always right, but it’s commonly right. It’s typically right. If you say something that takes everyone aback, therefore, you should reconsider what you said. I say that, knowing full well that controversial opinions are sometimes correct—sometimes so much so that the crowd will perish if it refuses to listen. It is for this reason, among others, that the individual is morally obliged to stand up and tell the truth of his or her own experience. But something new and radical is still almost always wrong. You need good, even great, reasons to ignore or defy general, public opinion. (emphasis mine)

Men are often accused of wanting to “fix things” too early on in a discussion. This frustrates men, who like to solve problems and to do it efficiently and who are in fact called upon frequently by women for precisely that purpose. It might be easier for my male readers to understand why this does not work, however, if they could realize and then remember that before a problem can be solved it must be formulated precisely. Women are often intent on formulating the problem when they are discussing something, and they need to be listened to—even questioned—to help ensure clarity in the formulation. Then, whatever problem is left, if any, can be helpfully solved.

A well-practised and competent public speaker addresses a single, identifiable person, watches that individual nod, shake his head, frown, or look confused, and responds appropriately and directly to those gestures and expressions. Then, after a few phrases, rounding out some idea, he switches to another audience member, and does the same thing.

The strategy of speaking to individuals is not only vital to the delivery of any message, it’s a useful antidote to fear of public speaking. No one wants to be stared at by hundreds of unfriendly, judgmental eyes. However, almost everybody can talk to just one attentive person. So, if you have to deliver a speech (another terrible phrase) then do that. Talk to the individuals in the audience—and don’t hide: not behind the podium, not with downcast eyes, not by speaking too quietly or mumbling, not by apologizing for your lack of brilliance or preparedness, not behind ideas that are not yours, and not behind clichés.

The final type of conversation, akin to listening, is a form of mutual exploration. It requires true reciprocity on the part of those listening and speaking. It allows all participants to express and organize their thoughts. A conversation of mutual exploration has a topic, generally complex, of genuine interest to the participants. Everyone participating is trying to solve a problem, instead of insisting on the a priori validity of their own positions. All are acting on the premise that they have something to learn. This kind of conversation constitutes active philosophy, the highest form of thought, and the best preparation for proper living.

Rule 10: Be precise in your speech

When things break down, what has been ignored rushes in. When things are no longer specified, with precision, the walls crumble, and chaos makes its presence known. When we’ve been careless, and let things slide, what we have refused to attend to gathers itself up, adopts a serpentine form, and strikes—often at the worst possible moment. It is then that we see what focused intent, precision of aim and careful attention protects us from.

Do you truly think it wise to let the catastrophe grow in the shadows, while you shrink and decrease and become ever more afraid?

Something is out there in the woods. You know that with certainty. But often it’s only a squirrel. If you refuse to look, however, then it’s a dragon, and you’re no knight: you’re a mouse confronting a lion; a rabbit, paralyzed by the gaze of a wolf. And I am not saying that it’s always a squirrel. Often it’s something truly terrible. But even what is terrible in actuality often pales in significance compared to what is terrible in imagination. And often what cannot be confronted because of its horror in imagination can in fact be confronted when reduced to its-still-admittedly-terrible actuality.

Rule 11: Do not bother children when they are skateboarding

They weren’t trying to be safe. They were trying to become competent—and it’s competence that makes people as safe as they can truly be. ...

When playgrounds are made too safe, kids either stop playing in them or start playing in unintended ways.

[Orwell] concluded that the tweed-wearing, armchair-philosophizing, victim-identifying, pity-and-contempt-dispensing social-reformer types frequently did not like the poor, as they claimed. Instead, they just hated the rich. They disguised their resentment and jealousy with piety, sanctimony and self-righteousness. Things in the unconscious—or on the social justice–dispensing leftist front—haven’t changed much, today.

Recently, I was invited to give a TEDx talk at a nearby university. Another professor talked first. He had been invited to speak because of his work—his genuinely fascinating, technical work.... He spoke instead about the threat human beings posed to the survival of the planet. ... Like far too many people, he had become anti-human, to the core. He had not walked as far down that road as my friend, but the same dread spirit animated them both.

He stood in front of a screen displaying an endless slow pan of a blocks-long Chinese high-tech factory. Hundreds of white-suited workers stood like sterile, inhuman robots behind their assembly lines, soundlessly inserting piece A into slot B. He told the audience—filled with bright young people—of the decision he and his wife had made to limit their number of children to one. He told them it was something they should all consider, if they wanted to regard themselves as ethical people. I felt that such a decision was properly considered—but only in his particular case (where less than one might have been even better). The many Chinese students in attendance sat stolidly through his moralizing. They thought, perhaps, of their parents’ escape from the horrors of Mao’s Cultural Revolution and its one-child policy. They thought, perhaps, of the vast improvement in living standard and freedom provided by the very same factories. A couple of them said as much in the question period that followed.

We’ve only just developed the conceptual tools and technologies that allow us to understand the web of life, however imperfectly. We deserve a bit of sympathy, in consequence, for the hypothetical outrage of our destructive behaviour. Sometimes we don’t know any better. Sometimes we do know better, but haven’t yet formulated any practical alternatives. It’s not as if life is easy for human beings, after all, even now—and it’s only a few decades ago that the majority of human beings were starving, diseased and illiterate.169 Wealthy as we are (increasingly, everywhere) we still only live decades that can be counted on our fingers. Even at present, it is the rare and fortunate family that does not contain at least one member with a serious illness—and all will face that problem eventually. We do what we can to make the best of things, in our vulnerability and fragility, and the planet is harder on us than we are on it. We could cut ourselves some slack.

No one in the modern world may without objection express the opinion that existence would be bettered by the absence of Jews, blacks, Muslims, or Englishmen. Why, then, is it virtuous to propose that the planet might be better off, if there were fewer people on it? I can’t help but see a skeletal, grinning face, gleeful at the possibility of the apocalypse, hiding not so very far behind such statements. And why does it so often seem to be the very people standing so visibly against prejudice who so often appear to feel obligated to denounce humanity itself?

Boys are suffering, in the modern world. They are more disobedient—negatively—or more independent—positively—than girls, and they suffer for this, throughout their pre-university educational career. They are less agreeable (agreeableness being a personality trait associated with compassion, empathy and avoidance of conflict) and less susceptible to anxiety and depression, at least after both sexes hit puberty. Boys’ interests tilt towards things; girls’ interests tilt towards people. Strikingly, these differences, strongly influenced by biological factors, are most pronounced in the Scandinavian societies where gender-equality has been pushed hardest: this is the opposite of what would be expected by those who insist, ever more loudly, that gender is a social construct. It isn’t. This isn’t a debate. The data are in.

Schools, which were set up in the late 1800s precisely to inculcate obedience, do not take kindly to provocative and daring behaviour, no matter how tough-minded and competent it might show a boy (or a girl) to be. (emphasis mine)

The following excerpt is very long, and deserves its own post, but I'll include it here as well.

[The Spanish Civil War] drew attention away from concurrent events in the Soviet Union. In the 1930s, during the Great Depression, the Stalinist Soviets sent two million kulaks, their richest peasants, to Siberia (those with a small number of cows, a couple of hired hands, or a few acres more than was typical). From the communist viewpoint, these kulaks had gathered their wealth by plundering those around them, and deserved their fate. Wealth signified oppression, and private property was theft. It was time for some equity. More than thirty thousand kulaks were shot on the spot. Many more met their fate at the hands of their most jealous, resentful and unproductive neighbours, who used the high ideals of communist collectivization to mask their murderous intent.

The kulaks were “enemies of the people,” apes, scum, vermin, filth and swine. “We will make soap out of the kulak,” claimed one particularly brutal cadre of city-dwellers, mobilized by party and Soviet executive committees, and sent out into the countryside. The kulaks were driven, naked, into the streets, beaten, and forced to dig their own graves. The women were raped. Their belongings were “expropriated,” which, in practice, meant that their houses were stripped down to the rafters and ceiling beams and everything was stolen. In many places, the non-kulak peasants resisted, particularly the women, who took to surrounding the persecuted families with their bodies. Such resistance proved futile. The kulaks who didn’t die were exiled to Siberia, often in the middle of the night. The trains started in February, in the bitter Russian cold. Housing of the most substandard kind awaited them upon arrival on the desert taiga. Many died, particularly children, from typhoid, measles and scarlet fever.

The “parasitical” kulaks were, in general, the most skillful and hardworking farmers. A small minority of people are responsible for most of the production in any field, and farming proved no different. Agricultural output crashed. What little remained was taken by force out of the countryside and into the cities. Rural people who went out into the fields after the harvest to glean single grains of wheat for their hungry families risked execution. Six million people died of starvation in the Ukraine, the breadbasket of the Soviet Union, in the 1930s. “To eat your own children is a barbarian act,” declared posters of the Soviet regime.

Despite more than mere rumours of such atrocities, attitudes towards communism remained consistently positive among many Western intellectuals. There were other things to worry about, and the Second World War allied the Soviet Union with the Western countries opposing Hitler, Mussolini and Hirohito. Certain watchful eyes remained open, nonetheless. Malcolm Muggeridge published a series of articles describing Soviet demolition of the peasantry as early as 1933, for the Manchester Guardian. George Orwell understood what was going on under Stalin, and he made it widely known. He published Animal Farm, a fable satirizing the Soviet Union, in 1945, despite encountering serious resistance to the book’s release. Many who should have known better retained their blindness for long after this. Nowhere was this truer than France, and nowhere truer in France than among the intellectuals.

France’s most famous mid-century philosopher, Jean-Paul Sartre, was a well-known communist, although not a card-carrier, until he denounced the Soviet incursion into Hungary in 1956. He remained an advocate for Marxism, nonetheless, and did not finally break with the Soviet Union until 1968, when the Soviets violently suppressed the Czechoslovakians during the Prague Spring.

No one could stand up for communism after The Gulag Archipelago—not even the communists themselves.

And yet Marxism is alive and well and thriving in 21st century America, particularly in academia, in the mainstream media, and among many of our politicians.

This is another long one—and I've cut a lot out. I include it because as I was reading, I recognized this philosophy as the virulent plague that is devastating our entire culture. Maybe this is why I should have studied philosophy more than physics in college—or maybe that's how I retained my sanity.

According to Derrida, hierarchical structures emerged only to include (the beneficiaries of that structure) and to exclude (everyone else, who were therefore oppressed). Even that claim wasn’t sufficiently radical. Derrida claimed that divisiveness and oppression were built right into language—built into the very categories we use to pragmatically simplify and negotiate the world. There are “women” only because men gain by excluding them. There are “males and females” only because members of that more heterogeneous group benefit by excluding the tiny minority of people whose biological sexuality is amorphous. Science only benefits the scientists. Politics only benefits the politicians. In Derrida’s view, hierarchies exist because they gain from oppressing those who are omitted. It is this ill-gotten gain that allows them to flourish. ...

It is almost impossible to over-estimate the nihilistic and destructive nature of this philosophy. It puts the act of categorization itself in doubt. It negates the idea that distinctions might be drawn between things for any reasons other than that of raw power. Biological distinctions between men and women? Despite the existence of an overwhelming, multi-disciplinary scientific literature indicating that sex differences are powerfully influenced by biological factors, science is just another game of power, for Derrida and his post-modern Marxist acolytes, making claims to benefit those at the pinnacle of the scientific world. There are no facts. Hierarchical position and reputation as a consequence of skill and competence? All definitions of skill and of competence are merely made up by those who benefit from them, to exclude others, and to benefit personally and selfishly.

I do not understand why our society is providing public funding to institutions and educators whose stated, conscious and explicit aim is the demolition of the culture that supports them. Such people have a perfect right to their opinions and actions, if they remain lawful. But they have no reasonable claim to public funding. If radical right-wingers were receiving state funding for political operations disguised as university courses, as the radical left-wingers clearly are, the uproar from progressives across North America would be deafening.

There isn’t a shred of hard evidence to support any of their central claims: that Western society is pathologically patriarchal; that the prime lesson of history is that men, rather than nature, were the primary source of the oppression of women (rather than, as in most cases, their partners and supporters); that all hierarchies are based on power and aimed at exclusion. Hierarchies exist for many reasons—some arguably valid, some not—and are incredibly ancient, evolutionarily speaking.

In societies that are well-functioning—not in comparison to a hypothetical utopia, but contrasted with other existing or historical cultures—competence, not power, is a prime determiner of status. Competence. Ability. Skill. Not power. This is obvious both anecdotally and factually. No one with brain cancer is equity-minded enough to refuse the service of the surgeon with the best education, the best reputation and, perhaps, the highest earnings. Furthermore, the most valid personality trait predictors of long-term success in Western countries are intelligence (as measured with cognitive ability or IQ tests) and conscientiousness (a trait characterized by industriousness and orderliness). ... The predictive power of these traits, mathematically and economically speaking, is exceptionally high—among the highest, in terms of power, of anything ever actually measured at the harder ends of the social sciences. A good battery of personality/cognitive tests can increase the probability of employing someone more competent than average from 50:50 to 85:15.

Assume ignorance before malevolence.

Agreeable, compassionate, empathic, conflict-averse people (all those traits group together) let people walk on them, and they get bitter. They sacrifice themselves for others, sometimes excessively, and cannot comprehend why that is not reciprocated. Agreeable people are compliant, and this robs them of their independence. The danger associated with this can be amplified by high trait neuroticism. Agreeable people will go along with whoever makes a suggestion, instead of insisting, at least sometimes, on their own way. So, they lose their way, and become indecisive and too easily swayed. If they are, in addition, easily frightened and hurt, they have even less reason to strike out on their own, as doing so exposes them to threat and danger (at least in the short term). That’s the pathway to dependent personality disorder, technically speaking.

If they’re healthy, women don’t want boys. They want men. They want someone to contend with; someone to grapple with. If they’re tough, they want someone tougher. If they’re smart, they want someone smarter. They desire someone who brings to the table something they can’t already provide. This often makes it hard for tough, smart, attractive women to find mates: there just aren’t that many men around who can outclass them enough to be considered desirable (who are higher, as one research publication put it, in “income, education, self-confidence, intelligence, dominance and social position”).

If you think tough men are dangerous, wait until you see what weak men are capable of. (emphasis mine)

Rule 12: Pet a cat when you encounter one on the street

The parts of your brain that generate anxiety are more interested in the fact that there is a plan than in the details of the plan.

Put the things you can control in order. Repair what is in disorder, and make what is already good better. It is possible that you can manage, if you are careful. People are very tough.

Coda

What shall I do with my parents? Act such that your actions justify the suffering they endured.

Exhaustion and impatience are inevitable. There is too much to be done and too little time in which to do it.

Our families can be the living room with the fireplace that is cozy and welcoming and warm while the storms of winter rage outside. (emphasis mine)

Excerpts from Beyond Order

Overture (introduction)

The order we strive to impose on the world can rigidify as a consequence of ill-advised attempts to eradicate from consideration all that is unknown.

What is new is also what is exciting, compelling, and provocative, assuming that the rate at which it is introduced does not intolerably undermine and destabilize our state of being. [emphasis mine]

Rule I: Do not carelessly denigrate social institutions or creative achievement

Authority is not mere power, and it is extremely unhelpful, even dangerous, to confuse the two. When people exert power over others, they compel them, forcefully. They apply the treat of privation or punishment so their subordinates have little choice but to act in a manner contrary to their personal needs, desires, and values. When people wield authority, by contrast, they do so because of their competence—a competence that is spontaneously recognized and appreciate by others, and generally followed willingly, with a certain relief, and with the sense that justice is being served.

The ideal personality cannot remain an unquestioning reflection of the current social state. Under normal conditions it may be nonetheless said that the ability to conform unquestioningly trumps the inability to conform. However, the refusal to conform when the social surround has become pathological—incomplete, archaic, willfully blind, or corrupt—is something of even higher value, as is the capacity to offer creative, valid alternatives. This leaves all of us with a permanent moral conundrum: When do we simply follow convention doing what others request or demand, and when to we rely on our own individual judgement, with all its limitations and biases, and reject the requirements of the collective? In other words: How do we establish a balance between reasonable conservatism and revitalizing creativity?

Discipline—subordination to the status quo, in one form or another—needs to be understood as a necessary precursor to creative transformation, rather than its enemy. ... [Creative transformation] must strain against limits. It has no use and cannot be called forth unless it is struggling against something.

It is necessary to conform, to be disciplined, and to follow the rules—to do humbly what others do; but it is also necessary to use judgment, vision, and the truth that guides conscience to tell what is right, when the rules suggest otherwise. It is the ability to manage this combination that truly characterizes the fully developed personality: the true hero.

Rule II: Imagine who you could be, and then aim single-mindedly at that

Rule III: Do not hide unwanted things in the fog

Rule IV: Notice that opportunity lurks where responsibility has been abdicated

If you want to become invaluable in a workplace—in any community—just do the useful things no one else is doing. Arrive earlier and leave later than your compatriots (but do not deny yourself your life). Organize what you can see is dangerously disorganized. Work, when you are working, instead of looking like you are working. And finally, learn more about the business—or your competitors—than you already know. Doing so will make you invaluable—a veritable lynchpin. People will notice that and begin to appreciate your heard-earned merits.

You might object, "Well, I just could not manage to take on something that important." What if you began to build yourself into a person who could? You could start by trying to solve a small problem—something that is bothering you, that you think you could fix. You could start by confronting a dragon of just the size that you are likely to defeat. A tiny serpent might not have had the time to hoard a lot of gold, but there might still be some treasure to be won, along with a reasonable probability of succeeding in such a quest (and not too much chance of a fiery or toothsome death).

Difficult is necessary.

It is for this reason that we voluntarily and happily place limitations on ourselves. Every time we play a game, for example, we accept a set of arbitrary restrictions. We narrow and limit ourselves, and explore the possibilities thereby revealed. That is what makes the game. ... It is a game anymore if you can make any old move at all.

How is it possible to gauge the rate at which challenges should be sought? It is the instinct for meaning—something far deeper and older than mere thought—that holds the answer. Does what you are attempting compel you forwards, without being too frightening? Does it grip your interest, without crushing you? Does it eliminate the burden of time passing? Does it serve those you love and, perhaps, even bring some good to your enemies? That is responsibility.

Rule V: Do not do what you hate

Rule VI: Abandon ideology

I find it heart-wrenching to see how little encouragement and guidance so many people have received, and how much good can emerge when just a little more is provided. "I knew you could do it" is a good start, and goes a long way toward ameliorating some of the unnecessary pain in the world.

When we meet, one on one, people tell me that they enjoy my lectures and what I have written because what I say and write provides them with the words they need to express things they already know, but are unable to articulate. It is helpful for everyone to be able to represent explicitly what they already implicitly understand. I am frequently plagued with doubts about the role that I am playing, so the fact that people find my words exist in accordance with their deep but heretofore unrealized or unexpressed beliefs is reassuring, helping me maintain faith in what I have learned and thought about and have now shared so publicly. Helping people bridge the gap between what they profoundly intuit but cannot articulate seems to be a reasonable and valuable function for a public intellectual.

I can attest to the value of such encouragement to one who has "shared so publicly." Among the nice things people have said to me about my blog, my absolute favorites are the variations on, "You wrote what I wanted to say but couldn't express."

You might even consider the inculcation of responsibility the fundamental purpose of society. But something has gone wrong. We have committed an error, or a series of errors. We have spent too much time, for example (much of the last fifty years), clamoring about rights, and we are no longer asking enough of the young people we are socializing. We have been telling them for decades to demand what they are owed by society. We have been implying that the important meanings of their lives will be given to them because of such demands, when we should have been doing the opposite: letting them know that the meaning that sustains life in all its tragedy and disappointment is to be found in shouldering a noble burden. Because we have not been doing this, they have grown up looking in all the wrong places. And this has left them vulnerable: vulnerable to easy answers and susceptible to the deadening force of resentment.

Ressentiment—hostile resentment—occurs when individual failure or insufficient status is blamed both on the system within which that failure or lowly status occurs and then, most particularly, on the people who have achieved success and high status within that system. The former, the system, is deemed by fiat to be unjust. The successful are deemed exploitative and corrupt, as they can be logically read as undeserving beneficiaries, as well as the voluntary, conscious, self-serving, and immoral supporters, if the system is unjust. Once this causal chain of thought has been accepted, all attacks on the successful can be construed as morally justified attempts at establishing justice—rather than, say, manifestations of envy and covetousness that might have traditionally been defined as shameful. [emphasis mine]