Yesterday was the first day of EPCOT's Flower and Garden Festival for 2016, and we were there to celebrate its opening. As always, the flower displays were wonderful, and the portable butterfly garden was fun.

Yesterday was the first day of EPCOT's Flower and Garden Festival for 2016, and we were there to celebrate its opening. As always, the flower displays were wonderful, and the portable butterfly garden was fun.

The only "ride" we bothered with this time was Impressions de France, the wonderful tour of the country accompanied by even more wonderful music by French composers. This film is one of the few parts of EPCOT that remains unchanged, and since we both agree that few of the changes have been for the better, the French pavillion has become an EPCOT "must do" for us, as Dr. Doom's Fearfall is at Universal.

You never know, with YouTube videos, when some official is going to decide one violates something-or-other and take it down, but for now, at least, you can see an excellent production by Martin Smith of his visit there in 2011. I trust Disney World recognizes it for what it is: a longer commercial for EPCOT than they could ever get away with.

Our Disney disappointment came with lunch, which we had intended to enjoy at Norway in World Showcase. Norway used to be one of our favorite stops because of the Maelstrom ride, which sadly is now closed in preparation for being replaced by something based on the movie, Frozen. Oh, how I miss the days when the company abided by Walt Disney's admonition that EPCOT should remain completely separate from the movie characters!

As it turns out, there is now no reason at all to visit the Norway site. The Akershus restaurant, where we had intended to eat, has been turned into a "Princess Storybook Dining" event, exclusively. We were greatly disappointed, as the delicious and authentic Scandinavian fare was something we were looking forward to when we sprang for annual park passes for the first time in many years. But we declined the experience, on the grounds that if we were going to spend over $50 per person for a meal, (1) we did not want a "Disney Princess experience," and (2) we wanted better food than we could expect from a restaurant whose primary audience is now children. Apparently the only other hope for Scandinavian food in Central Florida is IKEA, so you know what a blow this was.

It was hard to stay sad for long, however, since as part of the Flower and Garden Festival they have set up many additional food kiosks, in the manner of the Food and Wine Festival, and we enjoyed some good Moroccan snacks followed by a lemon scone with crème fraîche and blueberries.

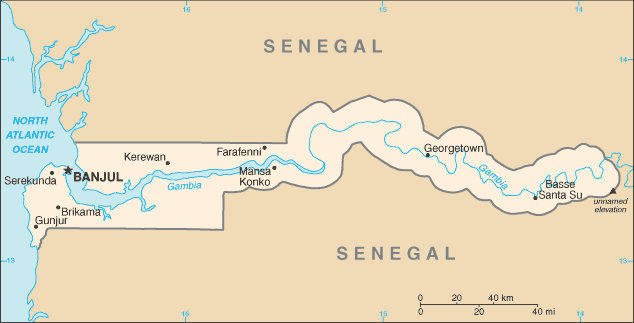

I've been overseas every year for the past decade, so it ought to be routine by now. But travelling to the Gambia is not like travelling to Japan or to Switzerland. For starters, we needed visas.

Most visitors to the Gambia don't need visas, but the United States is special. American tourists are required to fill out a bunch of paperwork and fork over $100 (each). Because we have family overseas, we are always a bit nervous when our passports are out of our hands, but the process went smoothly and we had them back, with the necessary visas, in just a few days.

.jpg) Then there was the medical side. Immunizations (yellow fever, typhoid, meningococcal, hepatitis A & B) and medications (malarone to be taken daily as an anti-malarial, Cipro in case of traveller's diarrhea, probiotics in case we had to use the Cipro) cost us some $1200. We were spared the rabies vaccine, although if the doctor had known how many stray dogs we were to encounter, the story might have been different. Our insurance company believes in funding preventive medicine, they say, but clearly their idea of tropical disease prevention is encouraging people to stay home.

Then there was the medical side. Immunizations (yellow fever, typhoid, meningococcal, hepatitis A & B) and medications (malarone to be taken daily as an anti-malarial, Cipro in case of traveller's diarrhea, probiotics in case we had to use the Cipro) cost us some $1200. We were spared the rabies vaccine, although if the doctor had known how many stray dogs we were to encounter, the story might have been different. Our insurance company believes in funding preventive medicine, they say, but clearly their idea of tropical disease prevention is encouraging people to stay home.

And finally, the new wardrobe. As nearly all of you know, I'm not a shopper, I don't care anything about clothes as long as they are comfortable, and the occasions for which I will put on a dress or a skirt are so rare as to be barely perceptible. (Weddings of family members. That's about it.) But then Kathy happened to mention—fortunately, in time for us to do something about the problem—that I'd need to wear a skirt or dress (mid-calf or longer) whenever we went out in public, and even at home if we had visitors.

I suppose most women would have just packed a few dresses and been fine. I needed to go shopping (oh, joy) and climb over a major psychological barrier. Dresses, after all, are the tools and symbols of oppression. Oppression of women by men, of children by parents, of students by teachers. Unless you happen to be the queen, or to live in Scotland, skirts are not associated with power.

While I might not be as sensitive as some in my family to shirt tags and wrinkles in my socks, it's still an issue for me, and I still remember, and not happily, the time when as a very young child I was required to wear a certain dress—beautiful, and hand-made with lots of love, but very scratchy—for an interminable period. Really, it was just long enough to go to the photographer's for a professional picture, but it was torture to me. I'm grateful that most of the time my mother was more merciful when it came to my clothes, but dresses = discomfort was ingrained in me from an early age.

And then there was school. As if school weren't oppressive enough all by itself, in those days all girls were required to wear dresses or skirts and blouses. Even on the playground, even in gym class. Girl Scout uniforms were dresses. Church clothes were dresses. Believe me, if it had been possible for me to get used to wearing skirts, I had plenty of opportunity to do so. It didn't happen.

On top of that, dresses in those days were not loose and flowy, but short and tight. It was the era of the miniskirt; even for the more conservative among us hemlines had to be above the knee, greatly limiting movement and action. A dress was a prison. But the times, they were a-changin.' When I went off to college I left my dresses behind me, and after graduation being a computer programmer allowed me to land a job without much in the way of a dress code. I'm not certain, but I think the next time I wore a skirt was at the rehearsal dinner before our wedding.

Hence my psychological shock at Kathy's statement. Oh, tourists can get away with anything for the sake of their euros, and students sometimes wear jeans and t-shirts, and the rules in that patriarchal society are much looser for men—though Porter still could not wear shorts despite being just 13.5 degrees away from the equator. But mature women do not show their legs in the Gambia. Not if they want to be respected. Kathy quite rightly did not want her American friends to embarrass her Gambian friends. We probably did, anyway, because Gambian women dress beautifully at all times, and even the men have a keen sense of style. But at least we weren't immodest. (Incidentally, Gambians have a much healthier attitude toward public breastfeeding than Americans; it's legs that have to stay covered.)

_WPW_GM_Fajara_Kathy, Linda walking along Kairaba Avenue.jpg) Nothing about the experience was as bad as the anticipation. The shopping was the worst, but Kohl's and Target (both online) came through with three acceptable skirts at reasonable prices. They were even comfortable, as skirts go, because they were soft and loose and long. I ended up only bringing two with me, not wanting to take the time to do necessary hemming on the last one, but why should I need more than two? We wouldn't be going out in public that much, would we? (Well, yes, we would. But two skirts were still sufficient.)

Nothing about the experience was as bad as the anticipation. The shopping was the worst, but Kohl's and Target (both online) came through with three acceptable skirts at reasonable prices. They were even comfortable, as skirts go, because they were soft and loose and long. I ended up only bringing two with me, not wanting to take the time to do necessary hemming on the last one, but why should I need more than two? We wouldn't be going out in public that much, would we? (Well, yes, we would. But two skirts were still sufficient.)

My sister-in-law made an odd but brilliant suggestion, in the form of mid-thigh underwear from the Vermont Country Store. I was skeptical, and indeed they did not suit me as underwear. But as something to wear under my skirt and over my usual underwear, they were perfect for the Gambian weather situation: temperatures in the 90's and no air conditioning. The over-underwear did a wonderful job of absorbing the sweat that otherwise poured uncomfortably down my legs. (As a Floridian, I'm accustomed to hot weather, but deal with it by [1] wearing shorts, and [2] relying on air conditioning.) There's also no overestimating the psychological value: they felt like shorts on my body, which helped undo some of the mental discomfort. I had one other trick up my sleeve as well: When I caught myself feeling overpowered and bowed down because I was wearing a skirt, I imagined being a Scottish chieftain, and that actually worked—even though my skirt could hardly have looked less like a kilt.

We were out in public a lot. As Kathy explained, the Gambia is a hard place to be an introvert. Although I would usually rip my skirt off in favor of shorts as soon as we walked in the door of her house—in order to cool down a little—for most of our two weeks in the Gambia, I lived in a skirt.

And we developed an uneasy friendship, the skirts and I. After returning home, I washed them and put them away in the back of our closet, so glad, as they say, to see the back of them. But one day, after sufficient time has passed, I will pull them out again and wear them for some occasion, perhaps a party. I'm glad to have them in my arsenal of clothing. Being loose, long, and of soft material they are a far cry from the dresses of my childhood. Besides, they are full of wonderful memories!

As for the rest of our trip preparations, I suppose they were mostly normal. We had our tickets, our visas, our "yellow cards" showing yellow fever immunizations, our anti-malarial meds, the proper clothing, and a few gifts. It was time to begin the adventure!

I know people who are fond of saying, as if it were original with them and somehow encouraging to others, that we should never ask for what we deserve, because what we all deserve is Hell. As unhelpful as this aphorism is, there are times when everyday life points to a kernel of truth there. We remember vividly the times when we've done something stupid and paid the price, or done something stupid and managed somehow to escape disaster, but we may not even be aware of how many, many times we've been equally stupid, or more so, and escaped scot free. How often have we taken a foolish chance while driving, or set a can of soda near the computer, or carried a large stack of breakable objects? How many times have we thought, "I knew that was going to happen" when a foolish risk has ended badly? Truly, when we know what we should do and act otherwise, do we deserve to escape the consequences? No—but surprising often, grace abounds anyway.

It's an old, sad story, and out of respect for those who, like me, are not fond of suspense, I'll say up front that this one has a happy ending.

I'm usually a bit compulsive when it comes to doing backups. I have general backups, and specific backups. Whole and incremental backups. Backups divided over several years and different external drives. But I'm not perfect about it, and this was one of those times.

Mostly I find a once-a-week backup sufficient for my needs, but recently I've been working pedal-to-the-metal on processing our photos and videos from the Gambia, so I got into the habit of backing up my work every night. See, I know the right thing to do! But one night the backup system gave me trouble. Instead of spending the next day sorting it out, I carried on feverishly with my work. I was making such good progress! Who could be bothered with a problem that was, I knew, going to be frustrating and time-consuming to sort out? So for a few days—highly productive days—that nightly backup didn't happen.

I'm a big fan of the recycle bin. I love that a deleted file doesn't really disappear right away, so that accidents and mistakes are reversible. However, some files, such as video files, are too big for such treatment. For those I use the shift-delete function, which bypasses the recycle bin and erases the file directly.

One morning I was working with a number of video files, and got a little too careless with my quick response to the "Are you sure you want to permanently delete this file?" question. I was certain I had highlighted the video I was done with, but Windows Explorer had other ideas. You want to delete the entire directory? The entire directory with your final processed photos? The directory that represents 60+ hours' worth of work? Fine, no problem, I can do that for you in under a second.

I stared at the computer. I didn't believe what appeared to have happened. I turned my computer inside out, searched from top to bottom. Finally I let myself admit that the files were gone. Completely. Gone.

I was surprisingly calm. Sometimes big events leave you too overwhelmed to be upset. Besides, I did have some backups, though they were, as I said, a few days old, and the most recent one had been corrupted by the above-mentioned problem. But as I also said, I'm usually compulsive about backups, and if I didn't have my work in final form, I did have it in next-to-final form, and the form before that, and the form before that. What had been done once could be done again, and though the magnitude of effort lost was mind-boggling, I took comfort in a comment reader-friend Eric once made here about work being done better the second time around.

As it turned out, we'll never know how much better I would have done the second time, and that's more than fine with me.

When files are deleted from a drive, even by shift-delete, they're not really erased. They're no longer visible to the user, but the data's there until it's overwritten. I knew that, but had no idea how to take advantage of it. Then a little Internet research led me to a data-recovery program called Recuva.

Had my files been on the C drive, I may have been in trouble, because I did quite a bit of work before finding that program, and the more time that elapses, the more likely the data is to be overwritten. But because of space considerations, my data was on an external drive that I had been careful not to write to since the loss. The operating system, or some other program not under my control, probably did something, but—to shorten the story—with the help of Recuva I was able to recover all but about half a dozen files. The few that had been damaged I easily recreated from the next-to-final layer. I'm very grateful I did not accidentally delete a higher-level directory!

Curious as to what an overwritten file looks like? Here are an original and its corrupted version. You can still see some of the basic structure. (Click to enlarge.)

Once I had the program downloaded and unzipped to a flash drive, using Recuva to restore the files was quick and easy. The long and tedious part of the job came in checking the integrity of the recovered files, but that only took five or six hours, and by the next day I was back to where I'd been 24 hours earlier.

With one important exception: I now have Recuva on that flash drive, available should I need it again. It's especially important to have it handy in case I ever need to recover files from the C drive, where overwriting can happen quickly. Which I sincerely hope never happens!

It's amazing how easy it is to accept the loss of a day's work—which normally would have had me tearing my hair—when faced with the realization that the loss could have been many times greater.

Truly, grace abounds.

Permalink | Read 2644 times | Comments (3)

Category Computing: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Travels: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Everyday Life: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] The Gambia: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

Joyce K. is a very good friend of our family, and though she has plenty of grandchildren of her own, she happily played a grandmotherly role to our children. Formerly of Philadelphia's Savoy Company, she is a great lover of Gilbert and Sullivan and introduced our kids to that joy at an early age, through a children's book version of "The Pirates of Penzance." I believe she also provided the taped-from-TV videotape now mouldering away lovingly preserved in our cupboard (the Rodney Greenberg version, starring Peter Allen as the Pirate King).

We nearly wore the tape out. When Janet went to kindergarten, and was interviewed for one of those "all about me" posters, she confounded her teacher by responding to the inane question, "What's your favorite TV show?" by answering, "The Pirates of Penzance." One of my joys of those years was hearing quotes from the show pop up in the girls' conversations.

Fueled by those memories, I let work grind to a halt today while I created an excerpt from that tape as an homage to this special, quadrennial day.

Permalink | Read 2103 times | Comments (0)

Category Just for Fun: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

The Fatal Tree by Stephen R. Lawhead (Thomas Nelson, 2014)

The Fatal Tree by Stephen R. Lawhead (Thomas Nelson, 2014)

This is the final book in Lawhead's Bright Empires series, of which the first four were The Skin Map, The Bone House, The Spirit Well, and The Shadow Lamp. I enjoyed reading The Fatal Tree, which only took me a few hours, but was nonetheless disappointed. As with my experience reading the Harry Potter books, this series got better and better for the first three books, then largely fell apart.

The premise—combining the concept of ley lines with quantum physics and multiverse theory—is brilliant, as are many of the ways the author works the concepts out in the lives of his characters. I wish the last two books had fulfilled the promise of the first three. The confusion of so many characters from many times and places, and the dizzying way the book jumps around, enhance the story in the early books, mimicking the confusion of ley travel and multiple universes, but sadly the last book does not draw all the threads into a coherent whole. Rather, it feels hasty and incomplete.

What's more, Lawhead is a Christian writer, and where his faith is kept in the backgound it adds depth and beauty to the stories. Unfortunately, when it becomes explicit, as in the last two books, it feels forced and awkward.

I still recommend the Bright Empires series, because Lawhead had a wonderful idea and worked it out in some very clever ways. I'd rank it well below The Lord of the Rings but well above Harry Potter. It's just a pity that Lawhead, like J. K. Rowling, stopped at good when he could have reached great.

Do you dream in color or in black and white?

This question, common in my childhood, must seem nonsense to the next generations, as to people throughout most of history.

I clearly remember dreaming in color, but just as clearly I know I frequently dreamt in black and white. The one vividly-colored dream I remember well occurred before we had a television set, and that's significant. What possible reason could there be for black and white dreams except the influence of black and white television?

I thought of that recently as I observed the curious phenomenon that dream time apparently bears no resemblance to real time. I wake up and look at the clock. Fifteen minutes later I awaken again and realize that although only fifteen minutes have passed, the dream I had awakened from had seemingly covered hours of time.

How does the brain do that? Is it natural, or is it, like the black and white dreams, a product of familiarity with the time-compression common to movies and television shows?

Permalink | Read 1888 times | Comments (1)

Category Random Musings: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

Manjiro: The Man who Discovered America by Hisakazu Kaneko (Riverside Press, 1956)

This book was apparently my paternal grandmother's: her name is scrawled with some other notes on the back of the dust jacket. I suspect it made its way to my bookshelves in one of the eight large boxes I took home when my father—a book lover indeed—moved out of our family home. Inspired by my 95 by 65 goal to read some of those books at last, I chose Manjiro to be my final book of 2015.

The only problem with this project is that I was hoping to declutter at the same time—but I keep finding such interesting books!

Manjiro was the impoverished, uneducated son of a Japanese widow, who by working on fishing boats helped his mother eke out a living. When he was 14, he was shipwrecked by a storm and rescued from a deserted island by an American whaling ship. Proving himself both bright and ambitious, he could have made a good life in Fairhaven, Massachusetts, the home of his rescuer and foster father. But Manjiro had dreams of helping his insular country open its doors to the wider world, and eventually made his way back home, not long before the arrival of Commodore Perry in 1853.

This book is not the only one written about Manjiro's experiences, but I love its style, which retains a feeling not only of 1950's America, but of Japanese culture as well.

There's more to the book than the quotes below, but I especially enjoyed his observations of mid-19th century America.

When he was invited by the Tokugawa Government, soon after Commodore Perry and his fleet appeared in the Bay of Uraga in 1853, he had a vital role to play for the wakening of the Japanese people to world civilization. Upon his arrival in Yedo, the former capital of Japan, he was examined by Magistrate Saemon Kawaji before he was officially taken into government service.

Answering the questions put to him by the investigating official, he revealed his own observations about America to the amazement of his listeners. Never can we overestimate the value of these observations which undoubtedly influenced the policy of the Tokugawa Government in favor of the opening of the country to foreign intercourse when Commodore Perry revisited Japan in February, 1854.

The next quotes are from Manjiro himself:

The country is generally blessed with a mild climate and it is rich in natural resources such as gold, silver, copper, iron, timber and other materials that are necessary for man's living. The land, being fertile, yields abundant crops of wheat, barley, com, beans and all sorts of vegetables, but rice is not grown there simply because they do not eat it.

Both men and women are generally good-looking but as they came from different countries of Europe, their features and the color of their eyes, hair and skin are not the same. They are usually tall in stature. They are by nature sturdy, vigorous, capable and warmhearted people. American women have quaint customs; for instance, some of them make a hole through the lobes of their ears and run a gold or silver ring through this hole as an ornament.

When a young man wants to marry, he looks for a young woman for himself, without asking a go-between to find one for him, as we do in Japan, and, if he succeeds in finding a suitable one, he asks her whether or not she is willing to marry him. If she says, "Yes," he tells her and his parents about it and then the young man and the young woman accompanied by their parents and friends go to church and ask the priest to perform the wedding ceremony. Then the priest asks the bridegroom, "Do you really want to have this young woman as your wife?" To which the young man says, "I do". Then the priest asks a similar question of the bride and when she says, "I do," he declares that they are man and wife. Afterward, cakes and refreshments are served and then the young man takes his bride on a pleasure trip.

Refined Americans generally do not touch liquor. Even if they do so they drink only a little, because they think that liquor makes men either lazy or quarrelsome. Vulgar Americans, however, drink just like Japanese, although drunkards are detested and despised. Even the whalers, who are hard drinkers while they are on a voyage, stop drinking once they are on shore. Moreover, the quality of liquor is inferior to Japanese sake, in spite of the fact that there are many kinds of liquor in America.

Americans invite a guest to a dinner at which fish, fowl and cakes are served, but to the best of my knowledge, a guest, however important he may be, is served with no liquor at all. He is often entertained with music instead when the dinner is over.

When a visitor enters the house he takes off his hat. They never bow to each other as politely as we do. The master of the house simply stretches out his right hand and the visitor also does the same and they shake hands with each other. While they exchange greetings, the master of the house invites the visitor to sit on a chair instead of the floor. As soon as business is over, the visitor takes leave of the house, because they do not want to waste time.

When a mother happens to have very little milk in her breasts to give her child, she gives of all things a cow's milk, as a substitute for a mother's milk. But it is true that no ill effect of this strange habit has been reported from any part of the country.

On every seventh day, people, high and low, stop their work and go to temple and keep their houses quiet, but on the other days they take pleasure by going into mountains and fields to hunt, while lower class Americans take their women to the seaside or hills and drink and bet and have a good time.

The temple is called church. The priest, who is an ordinary-looking man, has a wife and he even eats meat, unlike a Japanese priest. Even on the days of abstinence, he only refrains from eating animal meat and he does not hesitate to eat fowl or fish instead. The church is a big tower-looking building two or three hundred feet high. There is a large clock on the tower which tells the time. There is no image of Buddha inside this temple, where on every seventh day they worship what they call God who, in their faith, is the Creator of the World. There are many benches in the church on which people sit during the service. All the members of the church bring their Books to the service. The priest, on an elevated seat, tells his congregation to open the Book at such and such a place, and when this is done, the priest reads from the Book and he preaches the message of the text he has just read. The service over, they all leave the church. This kind of service is held also on board the ships.

Every year on the Fourth of July, they have a big celebration throughout the land in commemoration of a great victory of their country over England in a war which took place seventy-five years ago. On that day they display the weapons which they used in the war. They put on the uniforms, and armed with swords and guns, they put up sham fights and then parade the streets and make a great rejoicing on that day.

As the gun is regarded as the best weapon in America, they are well trained how to use it. When they go hunting they take small guns, but in war they use large guns since they are said to be more suitable for war. Ports and fortresses are protected by dozens of these large guns so that it would be extremely difficult to attack them successfully. Before Europeans came to America, the natives used bows and arrows, but these old-fashioned weapons proved quite powerless before firearms which were brought by Europeans. Now the bow and arrow has fallen into disuse in America. To the best of my knowledge, they have never used bamboo shields, as we do, although they use sometimes the shields of copper plates for the protection of the hull of a fighting ship. They are not well trained in swordsmanship or spearsmanship, however, so that in my opinion, in close fighting, a samurai could easily take on three Americans.

American men, even officials, do not carry swords as the samurai do. But when they go on a journey, even common men usually carry with them two or three pistols; their pistol is somewhat equivalent to the sword of a samurai. As I said before, their chief weapon is firearms and they are skillful in handling them. Moreover, as they have made a thorough study of the various weapons used by foreign armies, they believe that there are hardly any foreign weapons that can frighten them out of their wits.

More and more both fighting ships and merchant ships driven by the steam engine have been built of late in America. These steamships can be navigated in all directions irrespective of the current and wind and they can cover the distance of two hundred ri a day. The clever device with which these ships are built is something more than I can describe. While in America I had no chance to learn the trade of shipbuilding, so that I would not say that I can build one with confidence. Since I have looked at them carefully, however, I shall be able to direct our shipwrights to build one, if I could get hold of some foreign books on the subject.

While I was in America I did not hear any good or bad remarks in particular about our country but I did hear Americans say that the Japanese people were easily alarmed, even when they see a ship in distress approaching their shores for help, and how they shoot it on sight, when there was no real cause for alarm at all. I also heard them speak very highly of Japanese swords, which they believe that no other swords could possibly rival. I heard too that Yedo of Japan, together with Peking of China and London of England, are the three largest and finest cities of the world.

The book ends with a letter written to Manjiro's eldest son by U. S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt:

My dear Dr. Nakahama:

When Viscount Ishii was here in Washington he told me that you are living in Tokyo and we talked about your distinguished father.

You may not know that I am the grandson of Mr. Warren Delano of Fairhaven, who was part owner of the ship of Captain Whitfield which brought your father to Fairhaven. Your father lived, as I remembered it, at the house of Mr. Trippe, which was directly across the street from my grandfather's house, and when I was a boy, I well remember my grandfather telling me all about the little Japanese boy who went to school in Fairhaven and who went to church from time to time with the Delano family. I myself used to visit Fairhaven, and my mother's family still own the old house.

The name of Nakahama will always be remembered by my family, and I hope that if you or any of your family come to the United States that you will come to see us.

Believe me, my dear Dr. Nakahama,

Very sincerely yours,

FRANKLIN ROOSEVELT

The letter was written on June 8, 1933, just eight and a half years before our two countries would be fiercely at war.

My amusement for this week comes from all the folks who are questioning the right of Pope Francis to suggest that Donald Trump is not the Christian he claims to be. "Who is he to judge?" they wonder. Well, um ...

- What part of POPE don't they understand? He's the supreme head of the Catholic Church, which has been making such judgements for oh, almost two millennia. Remember the Spanish Inquisition? Martin Luther? Henry VIII? Not to mention anyone who wants to join the Church?

- Or any church, any religion. Most Mormons claim to be Christian, while a large number of Christians think otherwise. Protestants and Catholics have traditionally proclaimed each other "not true Christians." My friends who think they remain Jewish after having also become Christian tend to find that their community thinks otherwise. Ask Sunni and Shia Muslims what they think of each other's faith.

- How about any organization with standards and definitions for membership? Or even just traditions? I have a friend who claims I'm not a "real" Democrat—despite the fact that I've been a member of the Democratic Party since the day I first registered to vote, and even worked for a Democratic presidential candidate while I was still in high school—because I share several values with Republicans (and others with Libertarians, etc.).

I agree with those who assert that only God knows a person's heart, but in the meantime we mortals have to make what judgements we can with our imperfect knowledge. Whether or not Donald Trump is a Christian does not make a hill of beans difference to most voters. It matters to me as a human being, and a Christian myself—though Pope Francis may not agree with that label in my case, either, since I'm not Catholic—but as a voter? Meh. In my life the two worst presidents have been the most obviously Christian. (Present administration excepted; I'm holding back official judgement on that until time has given me some hindsight.) Faith means a lot, but what it does not mean is that you have the wisdom, knowledge, and courage to be the president of the United States.

I'm sorting through the photos from our Gambia trip. During our safari in the Fathala Game Reserve in Senegal, I hastily wrote down the names of the animals so that I could properly identify the pictures. That is, I wrote down what I thought I heard our guide say. Her English was excellent but heavily-accented, and I knew that what I heard could not possibly be right. But I wrote it as I heard it, counting on the Internet to help me after we returned home.

It did. For those of you who are curious,

"Rowland antelope" = roan antelope

"yellowbill asparagus" = yellow-billed oxpecker. I knew it couldn't be "asparagus," but that was the closest I could come.

"red vervet monkey" = "patas monkey." I am certain I heard "red vervet monkey," but I couldn't find any red vervet monkeys by name, although many images showed them as a brownish-red color, even though they are apparently often called green monkeys. Google also suggested red velvet cake, which didn't help. Then I found this Wikipedia article, which suggests this of the patas monkey (which looks very much like what we saw):

The patas monkey (Erythrocebus patas) ... is a ground-dwelling monkey distributed over semi-arid areas of West Africa, and into East Africa. It is the only species classified in the genus Erythrocebus. Recent phylogenetic evidence indicates that it is the closest relative of the vervet monkey (Chlorocebus aethiops), suggesting nomenclatural revision.

So I'm sticking with the name our African guides gave it.

Here are a couple from other parts of our stay:

"nests vled vivas yellow female" = some sort of weaver birds' nests, possibly village weaver, possibly Vieillot's weaver. This was a tough one, from our Janjanbureh trip. Fortunately, birding in the Gambia is a popular tourist activity, so that helped. Which particular weaver "vled" is supposed to represent, I can't guess.

"never die plant heal wound kill snake" = moringa plant. This was tougher than it should have been, because where I saw it, the plant had other plants growing with it, and its own leaves had been mostly stripped off. But finally I'm convinced that this is it, despite there being no mention online to confirm our host's contention that it kills, or even repels, snakes.

The rest I actually heard correctly, though I didn't write down as much as I would have liked to. "Write down" meant changing the file name of the camera image to include the label, not the easiest of ways to take notes, but it's what I had.

The Billion Dollar Spy by David E. Hoffman (Doubleday, 2015)

The Billion Dollar Spy by David E. Hoffman (Doubleday, 2015)

This is not a book I would necessarily have picked up myself, but Porter thought so highly of it that I couldn't resist.

He was right.

There are many, many reasons why the Berlin Wall finally came down and the Cold War ended, as varied as President Reagan's firm stand, internal weaknesses created by Communism, and the influence of the Catholic Church in Poland. The Billion Dollar Spy reveals yet another: Adolf Tolkachev, a Russian engineer who fought the system he loathed with the best weapon he could: giving critical information on Soviet military technology to the country best able to make use of it: the United States. This knowledge was beyond value.

Not that we didn't bungle again and again his attempts to help us. The incompetence of the CIA at certain times in history and its unfathomable paralysis at others had me cringing as I read. And in the end Tolkachev and his mission were brought down by a disgruntled former CIA employee who betrayed him to the KGB.

In the meantime, his work exceeded the CIA's wildest expectations, and the story as Hoffman tells it makes for great reading.

More than 40 years after Porter assisted a University of Rochester professor in the search for gravity waves, predicted by Albert Einstein 100 years ago, evidence of their existence has finally been found.

What are you not giving up on?

Permalink | Read 2239 times | Comments (0)

Category Random Musings: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

I was a Girl Scout in various forms (Brownies on up—no Daisies in those days) for most of my childhood. I've written before about my frustrations then and even more so now, so I'll limit today's comments to cookies.

Yes, it's Girl Scout cookie time again, the only time of the year I really appreciate the organization. Not that I can't get plenty (read, too much) in the way of good cookies outside of the Girl Scouts, but their Thin Mints are unique and have been part of my life as long as I can remember. When the girls were young and living at home, we'd buy a case of Thin Mints every year, stick them in the freezer, and dole them out at the rate of one box per month.

This year we tried something new: in addition to the Thin Mints (now half-case) we bought a box of their Lemonades. Meh. Good but not exceptional, not worth the extra price over lemon Oreos.

After purchasing our cookies this year, I reflected how far the Girls Scouts have come in their salesmanship since I sold the cookies door-to-door for 40 cents a box. (The price is now an order of magnitude higher, and I'm sure there is less in the box. But we still buy them.) Back in the day we had to take orders, then go back some weeks later to deliver the actual cookies. Now, the girls have a booth set up in the fellowship area after church, with piles of boxes of cookies ready-to-hand. You see the merchandise, hand over your money, and walk off with boxes of delicious cookies. I know they must sell so much more that way than by the sight-unseen, place-an-order method.

But wait. Not everyone has gotten with the program. A few days later, three little girls in Girl Scout uniforms rang our doorbell and offered to sell us cookies. I had to explain that we had already bought ours for the year. If they had had the cookies right there with them, I'd have bought another box anyway, just to avoid disappointing them. But they did not. They were stuck in the order-taking days.

We've bought cookies at church, outside the grocery store, and even at Outback Steakhouse. I don't know how troops get permission to set up in these public places, but I find it a happier solution all around. Now that's a Girl Scout innovation I can get behind. Probably the only one...

Permalink | Read 2367 times | Comments (4)

Category Everyday Life: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

The Story of Western Science: From the writings of Aristotle to the Big Bang Theory by Susan Wise Bauer (W. W. Norton, 2015)

The Story of Western Science: From the writings of Aristotle to the Big Bang Theory by Susan Wise Bauer (W. W. Norton, 2015)

I didn't intend to read this book yet. I had put it on my Amazon wish list with the thought that I might receive it for Christmas. I've barely started Bauer's The History of the Renaissance World (95 by 65 goal number 64), which I felt I should finish before starting another of her books. But then our library purchased the book, and I thought it would be a good idea to skim it and make sure I wanted to keep it on my wish list. I quickly became hooked.

(The book I read had a slightly different title, though apparently the same content. According to Bauer, it "was originally published as The Story of Science, but my publisher has now changed the title to The Story of Western Science." Does that mean they expect a sequel about Eastern science?)

In keeping with the pattern Bauer set with her books of history, this is not so much the history of science as the story of science.

It traces the development of great science writing—the essays and books that have most directly affected and changed the course of scientific investigation. It is intended for the interested and intelligent nonspecialist. It shows science to be a very human pursuit: not an infallible guide to truth, but a deeply personal, sometimes flawed, often misleading, frequently brilliant way of understanding the world.

Each part presents a chronological series of "great books" of science, from the most ancient works of Hippocrates, Aristotle, and Plato, all the way up to the modern works of Richard Dawkins, Stephen Jay Gould, James Gleick, and Walter Alvarez. The chapters provide all of the historical, biographical, and technical information you need to understand the books themselves.

Not that it's necessary to read the books themselves. Bauer's chapters can stand alone to provide a solid introduction not only to the development of science, but to the science itself, on an intelligent but non-technical level. For those who want to dig deeper, Bauer's website provides excerpts from the older and less accessible books. Deeper still? She recommends sources for the originals (translations where necessary) in both print and electronic formats.

Most of us are fed science in news reports, interactive graphs, and sound bites. These may give us a fuzzy and incomplete glimpse of the facts involved, but the ongoing science battles of the twenty-first century show that the facts aren't enough. Decisions that affect stem cell research, global warming, the teaching of evolution in elementary schools—these are being made by voters (or, independently, by their theoretical representatives) who don't actually understand why biologists think stem cells are important, or how environmental scientists came to the conclusion that the earth is warming, or what the Big Bang actually is.

Scientists who grapple with biological origins are still affected by Platonic idealism today; Charles Lyell's nineteenth-century geological theories still influence our understanding of human evolution; quantum theory is still wrestling with Francis Bacon's methods.

To interpret science, we have to know something about its past. We have to continually ask not just "What have we discovered?" but also "Why did we look for it?" In no other way can we begin to grasp why we prize, or disregard, scientific knowledge in the way we do; or be able to distinguish between the promises that science can fulfill and those we should receive with some careful skepticism.

Only then will we begin to understand science.

The Story of Western Science is a solid, intellectual work, but not intimidating. I think our twelve-year-old grandson would enjoy it, and lay a solid foundation for further growth. His nine-year-old brother might even get something from reading through it, though both would benefit from rereading it at a later date. So would I—and I have a degree in mathematics and a stronger background in physics than most.

The book is also a pleasure to read because Susan Wise Bauer writes so well. I do object to her persistent use of the term "different than" instead of "different from," which is a pet peeve of mine—but that's easy to forgive for the overall delight her writing brings. I recommend The Story of Western Science wholeheartedly.

Having read it, however, there's no longer any reason to keep it on my Amazon list—unless, of course, for the sake of those aforementioned grandchildren.

I know there are Donald Trump supporters out there. I don't have the right to say much about them, as I don't know any of them, not even on Facebook. I do know some Bernie Sanders supporters, and the passion with which they believe in him. I'm going to go out on a limb, however, angering them all, I'm sure, and say that both camps have much more in common than they will ever believe.

They don't care much about history, economic theory, or diplomacy, and they are each pushing for paths that can take our country down, fast. What they do know is that things are badly wrong, and they're rightfully upset about it. Never mind that they think it's different things that are wrong.

The "anything is better than what we have" mentality really doesn't know—or doesn't believe—how bad things can be. (See above comment about ignorance of history—and of many other present-day cultures for that matter.) All the same, it doesn't do well for any political party to ignore the needs and frustrations of the people until so much pressure builds up that all hope of rationality is gone. This is what gave us the Affordable Care Act instead of a reasonable, workable, affordable approach to health care. (Have I mentioned that the Swiss health care law both works and is only sixty-some pages long? Though even they admit to being dependent on American pharmaceutical innovation that may well be on its way out now.)

Porter found this article that explains Donald Trump's popularity, and importance, better than anything I've seen yet: "Donald Trump is Shocking, Vulgar, and Right: And, my dear fellow Republicans, he's all your fault.

Consider the conservative nonprofit establishment, which seems to employ most right-of-center adults in Washington. Over the past 40 years, how much donated money have all those think tanks and foundations consumed? ... Has America become more conservative over that same period? Come on. Most of that cash went to self-perpetuation. ... Pretty embarrassing. And yet they’re not embarrassed.

Conservative voters are being scolded for supporting a candidate they consider conservative because it would be bad for conservatism? And by the way, the people doing the scolding? They’re the ones who’ve been advocating for open borders, and nation-building in countries whose populations hate us, and trade deals that eliminated jobs while enriching their donors, all while implicitly mocking the base for its worries about abortion and gay marriage and the pace of demographic change. Now they’re telling their voters to shut up and obey, and if they don’t, they’re liberal.

On immigration policy, party elders were caught completely by surprise. Even canny operators like Ted Cruz didn’t appreciate the depth of voter anger on the subject. And why would they? If you live in an affluent ZIP code, it’s hard to see a downside to mass low-wage immigration. Your kids don’t go to public school. You don’t take the bus or use the emergency room for health care. No immigrant is competing for your job. (The day Hondurans start getting hired as green energy lobbyists is the day my neighbors become nativists.) Plus, you get cheap servants, and get to feel welcoming and virtuous while paying them less per hour than your kids make at a summer job on Nantucket. It’s all good.

When was the last time you stopped yourself from saying something you believed to be true for fear of being punished or criticized for saying it? If you live in America, it probably hasn’t been long. That’s not just a talking point about political correctness. It’s the central problem with our national conversation, the main reason our debates are so stilted and useless. You can’t fix a problem if you don’t have the words to describe it. You can’t even think about it clearly.

This depressing fact made Trump’s political career. In a country where almost everyone in public life lies reflexively, it’s thrilling to hear someone say what he really thinks, even if you believe he’s wrong. It’s especially exciting when you suspect he’s right.

Now if only someone will do the same thing for the Democrats and Bernie Sanders.

Many of you know that we recently returned from a two-week trip to the Gambia, that tiny country within Senegal in West Africa. Since I never fully appreciate an experience until I've written about it, I've started a new category here, in which I'll put both travel memories and Gambia-inspired musings. Expect it to be rather random; if I wait to get it all organized I'll have forgotten too much. (Lots of thinking to do, many activities, and over 1600 photos.) In the meantime, here's some background.

After a couple of false starts some 45 years ago, I finally found a college roommate who became a friend for life. (Realize that in those dark ages, even smokers and non-smokers were often paired up to live together!) Kathy went on to get a Ph.D. in mathematics and enjoy a long career as a university professor with a well-deserved reputation as an excellent and caring teacher. Several years ago she embarked on a different sort of adventure altogether, and is now a math professor (and department chair) at the University of the Gambia, with an even stronger reputation for both excellence and caring. She's not there for the adventure (although there is plenty of that), nor for the salary (meagre), and certainly not for the working conditions, but to make a difference in the world. Yes, she's a saint, a fact of which I'm all the more convinced since our visit. (You can ignore this part, Kathy, assuming your flaky Internet connection lets you see it. You and I both know you're still the crazy person I knew back in college.) Perhaps it's more useful—since labelling people as saints tends to put them out of reach—to say that she's a Christian called by God to use her skills and experience in an unusual place. However you look at it, she's there, and is making a difference. The world, Africa, the Gambia, even the University—these are too large to exhibit visible change. But without a doubt she has for a number of years been changing the lives of families and individuals for the better.

However, despite the University's state of denial, she won't be in the Gambia forever. Hence our determination to seize the year (and the presence of this trip on my 95 by 65 list). The only reasonable time to make the trip was in January, which is during the dry season and between semesters for Kathy. Coming during the dry season turns out to be very, very important: the weather, though still hot (90's) is much more pleasant, the mosquitos are much less numerous, and transportation tends to be through a few inches of dust instead of a foot or more of garbage-and-water. Definitely the time to go!

So we went.

Some people travel for adventure. Others for the educational and cultural growth. As much as I value the latter, the primary importance of travel for me is still being with family and friends—and specifically, seeing them in their native habitat, as it were, so that their stories and experiences have more meaning when I hear them from far away. The educational experiences are a great bonus thrown in, and on this trip we even had a few adventures.

Stay tuned.