Love Does: Discover a Secretly Incredible Life in an Ordinary World by Bob Goff (Thomas Nelson, 2012)

Love Does: Discover a Secretly Incredible Life in an Ordinary World by Bob Goff (Thomas Nelson, 2012)

I learned of Bob Goff through reading A Million Miles in a Thousand Years by Donald Miller. To me, the story of how Goff and his family became friends with heads of state from around the world was by far the best part of the book. But I never followed up, never looked further into the man and what he might be doing.

It was Janet who tossed his name back in my direction. She distills the best of Love Does in her post at Blue Ocean Families, so be sure to read it.

I could say that Bob Goff is the anti-me, both good and bad. He epitomizes extroversion and spontaneity. He cares little for details and less for the kind of theology that involves studying. He is a loose cannon—at first I wondered why all those non-profit organizations turned down his offer of the services of his law firm, gratis, but now I think I know why they wanted someone more predictable, if also more expensive and less creative.

However, I am inclined to believe that the Bob Goff who shows up in this book is an exaggeration of his character for dramatic effect: Surely no one can succeed as a lawyer, not to mention as the head of a non-profit organization, without caring more for structure, organization, and planning than the man portrayed here.

Take your ten-year-old daughter on a spur-of-the-moment trip to London, without the least idea of what you're going to do, not even where you're going to stay? Okay, I can see that. They speak English (of a sort) there, he's an experienced traveller, and he has enough money to fund last-minute air fares and hotel stays.

Take your ten-your-old son climbing Half Dome in a blizzard, on purpose? As one with personal connections to the expert and experienced climbers who perished on Mt. Hood in 2006 due to unexpected bad weather, this strikes me as less adventuresome than plain stupid, even if it turned out to be a great experience for them both.

I have to believe that Goff was much more prepared for both adventures than he lets on.

There's no doubt, however, that a good deal of that preparation was provided by a lifetime of sponanteous action. Bob Goff lived the "just do it" slogan long before it became a Nike ad, and his life is a testimony to the incredible things that can arise from that attitude. As Janet's article states, what he has done is so amazing that it's hard to imagine him as a role model for us ordinary mortals. But he certainly can be an inspiration.

To that end, I do not necessarily recommend reading Love Does. At least not first. Instead, go to Goff's website. You'll get a good introduction there, and his informal style works better in a speech or on a blog than in a book.

It was in the fifteenth chapter that I learned why the style of Love Does bothers me so.

Don is a friend of mine. He's written a bunch of books. ... Don actually played a big part in this book. He would review what I wrote and tell me to keep working on it or take it out of the book. Sometimes he'd tell me to start over entirely or tell me what to do to make it better.

That's right; the above-mentioned Don Miller, whose style rubbed me the wrong way in A Million Miles in a Thousand Years, was the primary influence on how Goff wrote his book.

Here's an example of his fingernails-on-the-blackboard style, which I acknowledge some will enjoy. Just not me, if it's in a book or other formal publication.

In the Bible there's a guy named Timothy who gets a letter from another guy named Paul.

What also sets my teeth on edge is the number of times I've groaned, "Didn't anybody read this book before publishing it?" I don't blame Goff so much—it's hard to find the errors in one's own writing. But where were the proofreaders and editors here? Where was Don Miller? How, for example, could they publish "laundry mat" instead of "laundromat," "cast" instead of "caste," "track homes" instead of "tract homes," and "chalks" instead of "chocks" (the last from his website)?

I'm nitpicking, you say, and you're right. Neither the style nor the errors negate the value of what Bob Goff has to say. Nevertheless, there's a reason even the most brilliant job-seeker is advised to dress appropriately for his employment interview, and the most innocent (as well as the most guilty) defendant to ditch the nose ring and cover the tats for a court appearance. Even Bill Gates has assistants to keep his personality quirks from reducing his effectiveness.

Okay, I'm done with the complaints. Bob Goff is amazing, and inspiring. I just need to find my own path to being secretly incredible.

I think God's hope and plan for us is pretty simple to figure out. For those who resonate with formulas, here it is: add your whole life, your loves, your passions, and your interests together with what God said He wants us to be about, and that's your answer. If you want to know the answer to the bigger question—what's God's plan for the whole world?—buckle up, it's us.

Being secretly incredible goes against the trend that says to do anything incredible you have to buy furniture and a laptop, start an organization, have a mission statement and labor endlessly over a statement of faith. Secretly incredible people just do things. ... [T]he task would probably be even nobler if we didn't talk about it and just did it instead. It's not about being secretive or mysterious or exclusive. it's about doing capers without any capes.

Sometimes my clients have to be deposed, which means they are the ones asked questions by the other guys' lawyers. It can feel intimidating with a big room full of lawyers all staring at you. So when my clients are being deposed, I tell them all the same thing each time: sit in the chair and answer the questions, but do it with your hands palms up the whole time. I tell them to literally have the backs of their hands on their knees and their palms toward the bottom of the table.

I'm very serious about this. ... When their palms are up, they have an easier time being calm, honest, and accurate. And this is important, because it's harder for them to get defensive. When people get angry or defensive they tend to make mistakes.

If you're like me, I'd ask myself at the end of a book called Love Does—so what do I do? It can be a tough question to answer, honestly, but it can also be an easy one. Let me tell you want I do when I don't know what to do to move my dreams down the road. I usually just try to figure out what the next step is and then do that. ... What's your next step? I don't know for sure, because for everyone it's different, but I bet it involves choosing something that already lights you up. Something you already think is beautiful or lasting and meaningful. Pick something you aren't just able to do; instead, pick something you feel like you were made to do and then do lots of that.

On the face of it, July - September was a slow quarter for my 95 by 65 project. I completely only three goals in the three-month period:

- #57 Finish chronological Bible reading plan

- #37 Share at least 20 meals with others (home or restaurant, but not counting multi-day visits more than once or shared meals already in place)

- #94 Rocket boost photo work (40 hours of work in segments of 1 or more hours, over approximately 2 weeks)

To complete my goals by age 65, I need to average slightly over three goals per month, not per quarter.

Maybe I'm being overly optimistic, but I'm still not worried. Not by the numbers, anyway, because I know I'm making progress on many goals that by their nature take a long time to complete.

I do, however, continue to be ever-cognizant of the preciousness of time. When I look at the imposing quantity of time necessary for some of my projects, and watch the calendar on my phone tick over another day with such relentless frequency, it's hard to shake a minor but persistent panic. I'm keep in mind the following quote from George MacDonald, but have yet to succeed in working it out in my daily life:

He that believes shall not make haste. There is plenty of time. You must not imagine that the result depends on you, or me. The question is, are you having a hand in the work God is doing? It shows no faith in God to make frantic efforts or lamentations. God will do his work in his time in his way. Our responsibility is merely to stand ready and available and to go where he sends us and do what comes our way.

Another problem is that crossing goals off my list doesn't necessarily cross them out of my daily life. Completing my "try new restaurants" goal doesn't mean we stop going out to eat, and finishing one Bible reading plan merely means beginning another. Recently I completed Goal #65 Achieve 40,000 DuoLingo points. Yet that completion won't gain me any time, at least I hope not, because I'm finding the DuoLingo lessons both enjoyable and valuable and plan to continue the work. I can't let that suffer the fate of #16 Practice deliberate relaxation twice a day for a month, which did me so much good I intended to keep up the practice after meeting the goal, but.... I do intend to restart it, I do.

I have always disliked the "bucket list" idea. I'm not sure why; perhaps my deep-seated anxiety about time as a limited resource rebels at the name—as yet another, mocking, reminder. The 95 by 65 list serves me well as a way to achieve the concentrated attention of a bucket list with a more immediate and optimistic focus.

Onward!

That's the Swiss: chill, neutral, and convinced that Americans dress funny every day of the year. Mallard Fillmore from the day before the Swiss celebrate All Saints' Day.

Permalink | Read 2510 times | Comments (0)

Category Just for Fun: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

Porter read a review of The Martian that made him want to see it in a theater instead of waiting for it to become available on Netflix.

I believe the previous time we watched a movie in the theater was Christmas of 2013, when we saw part two of The Hobbit with some of our nephews and their friends. The social aspect seems to me about the only reason to go to a theater, and even for that I prefer watching at home, since at the theater you can't pause the movie to discuss it, nor rewind to catch a bit of dialogue you missed.

Another reason is for the sensory experience of the large screen and speakers, and in this case, the 3D effects. These are largely lost on me: I'm just as happy with the picture on our relatively small-screen TV, and I wear earplugs to protect my ears from the booming speakers. I have little experience with 3D movies beyond the kind they have at Disney World—where things jump out at you and are accompanied by puffs of air at your legs and vibrations of your seat. For The Martian the effects were simply visual, with nothing even to make me jump, and I don't think it added anything to the film, certainly not enough to warrant wearing the annoying glasses. Then again, I'm not one to be all that aware of dimensionality in the real world, so your mileage may vary.

The movie itself? It was good. Unusually good. I'm not much of a movie fan, and it takes a lot to get a "good" rating out of me. I'm told that The Martian is unusually true to the book, which was unusually well-researched and true to the science and engineering behind space travel. For people like us, who grew up in the era of manned space exploration, it does ring (mostly) true, not only in the technical aspects but also in the characters, from astronauts to politicians. It's an edge-of-your-seat thriller with a satisfying ending. I'd recommend it heartily were it not for one disturbing problem.

Why, O why do novelists and filmmakers believe they must include gratuitous profanity in their works? The Martian is otherwise SFG (Safe For Grandchildren), and I should be happy enough that this is a popular, mainstream, modern movie with neither sex nor shootouts. Instead there's resourcefulness, loyalty, determination, and celebration of both cooperative work and the lone-ranger nerd. But the bad language added less to the film than the 3D effects—and was more annoying than the special glasses—while taking a valuable, educational, and inspirational experience off the table for some boys I know who would have enjoyed it a lot.

Bad language aside—and there's not that much of it—if you liked Apollo 13, you won't want to miss The Martian.

We're 47th in line at the library for the book.

Rather cool, even if we do all have our mouths open. (Click to enlarge, or follow this link.)

Porter loves bougainvilleas—so do I, though not nearly with the same passion—and years ago planted some out front. He was so disappointed when they seemed to make little progress, and didn't bloom much.

Well, I don't know what happened, but in the last year or so they seemed to be determined to make up for those years all at once. One of the bushes is growing so aggressively that its thorns threatened people attempting to walk to our front door. I did briefly consider leaving it that way as a deterrent to solicitors, but since that would exclude Girl Scout cookies and LBHS Band apples, I gave up the idea. (Click on photos to enlarge.)

Instead, Porter built a pergola. He build the basic structure in the garage at first, then moved to the driveway to replace the temporary stubs with the 10.5 foot legs. After he dug the holes, we (yes, just he and I) lifted it, in halves, and put it into place. Then after levelling, and settling, and fastening it back together, he added the rest of the top pieces ...

... and filled in the holes, and introduced the bougainvilleas to their new plaything ...

... and we have a pergola! Isn't it pretty? I particularly like the sculpting he did on the ends.

Permalink | Read 2264 times | Comments (1)

Category Everyday Life: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

Today is the commemoration of the 600th anniversary of the Battle of Agincourt. I will set aside any worries over small details like calendar changes, and big details like historical accuracy, because Shakespeare's Henry V is a wonderful play, and his St. Crispin's Day speech one of the most inspiring and uplifting of all time. Kenneth Branagh does it best.

Food Foolish: The Hidden Connection Between Food Waste, Hunger and Climate Change by John M. Mandyck and Eric B. Schultz (Carrier Corporation, 2015)

Food Foolish: The Hidden Connection Between Food Waste, Hunger and Climate Change by John M. Mandyck and Eric B. Schultz (Carrier Corporation, 2015)

Have you ever heard of a cold chain? Me, neither. Yet we have depended on cold chains all our lives. If you don't drink your milk as it comes from the cow, then your life depends its being kept cold, whether it goes straight from the cow to your refrigerator, or travels thousands of miles in a refrigerated truck before being placed in the refrigerated dairy section of your grocery store. That vaccine your child just received? Useless, if it hasn't been kept sufficiently cool on its way from the manufacturer. Unless they're kept cool, fruits and vegetables start rotting the moment they're picked, losing flavor and nutrition, eventually becoming unusable.

The cold chain explains why the Carrier Corporation published Food Foolish. Keeping things cool is their business, and they've made it their business to develop sustainable technologies to do so. Along the way, they discovered a shocking truth: At least a third of all the food we produce in a year is never eaten.

The impact of food waste on hunger, climate change, natural resources and food security is enormous. It's changing the way we think about our product and technology development. It's strengthening our commitment to sustainable innovation. It's also prompting us to convene research and food chain experts to find solutions. We believe that food waste is an issue that must be elevated and examined globally. That's why we published Food Foolish. It's not an attempt to be the final word on the topic of food waste. Rather, it's meant to connect the issues of hunger, resource conservation and climate mitigation. We hope it will be a catalyst for more meaningful global dialogue which, many think, is essential to the sustainability of the planet.

That's why Carrier published the book. What do the authors say about why they wrote it?

Hunger, food security, climate emissions and water shortages are anything but foolish topics. The way we systematically waste food in the face of these challenges, however, is one of humankind's unintended but most foolish practices. We wrote this book to call attention to the extraordinary social and environmental opportunities created by wasting less food. We are optimistic that real solutions to feeding the world and preserving its resources can be unlocked in the context of mitigating climate change.

Food Foolish is a small book (182 pages) but very powerful. We're reasonably conservationist-minded around here, having been brought up that way. I feel pretty good that we put very little trash out on solid-waste pickup day, and the reason there's not usually much in our recycling bins is that we consume far less soda and beer than average. We take short showers and are in other ways mindful of our water use. Except for animal products, almost all of our food waste goes to feed our composting worms.

Ah. Our food waste. That broccoli that got shoved to the back of the refrigerator and forgotten? It fed the worms, so it's all good. Or maybe not....

When we consider ways to protect our fragile water resources, we need to look first and foremost at the global food supply chain. California provides one good example. The state produces nearly half of all U.S. fruits, vegetables and nuts from the very areas hardest hit by drought. Monterey County alone produces about half of the country's lettuce and broccoli.

Now imagine a consumer rummaging around in the back of his refrigerator's vegetable drawer only to find a forgotten head of broccoli, now yellow and unappetizing. He drops it in the trash. No big deal, right?

But wait: Fresh broccoli is about 91 percent water, and that's just the start. It actually takes a farmer about 5.4 gallons of water to grow that single head of broccoli. Just as each food product has an embedded carbon footprint, it also has a quantity of embedded freshwater from its journey along the food supply chain. In fact, a single person blessed with a healthy, nutritious diet will drink up to a gallon of water per day but "eat" up to 1,300 gallons of embedded freshwater in his food.

This little book stuck a sharp pin in my pride. Sure, it's better that the worms ate our spoiled broccoli than if it had gone into the landfill. But it was still a terrible waste. There's a lot more cost to producing food than what we see at the cash register. Water, fertilizer, pesticides, depletion of the soil, labor, storage, transportation—the human and environmental costs of that head of broccoli make it far too costly to become mere worm food.

Food waste also has a devastating impact on the environment. The water used to grow just the food we discard is greater than the water used by any single nation in the world.

[I]f food waste were a country by itself, it would be the third largest emitter of greenhouse gases behind China and the United states. Yet the connection between food waste and climate change is missing from policy discussions and public discourse.

Throughout history, human ingenuity has consistently foiled those who prophecy imminent doom in the form of mass starvation. Thomas Malthus (in 1798) and Paul Ehrlich (in 1968) both assured us that population growth inevitably leads to massive famine. Ehrlich specifically predicted that no matter what we tried to do about it, hundreds of millions of people were going to starve to death in the 1970's.

Fortunately, both Malthus and Ehrlich were wrong. Since The Population Bomb was published in 1968, the world's population has doubled to over 7 billion people. Despite this increase, humankind has managed to grow its food supply faster than its population. Eighty percent of the victims of famine in the last century died before 1965. Since the mid-20th century, famine has been more a function of civil disruption than of limited food supply.

The Green Revolution spiked Ehrlich's misanthropic guns, but the concern is back, and with reason. Dependent as it is on oil-based fertilizer, irrigation, and monoculture crop farming, the Green Revolution in its original form is not sustainable. A different kind of agricultural revolution is needed.

The political will exists to improve upon the gains of the Green Revolution, bu the landscape has changed. While the focus remains on alleviating chronic hunger, there has emerged a fundamental understanding that simply expanding farmland and improving crop yields are insufficient to feed a growing planet. Any new solution must be sustainable. ... Observers agree that if humankind wants to engineer a new "miracle" to help feed our growing planet, it must be fundamentally different in shape and substance from the Green Revolution of the 20th century.

Enter food waste awareness. By the numbers, if we could eliminate food loss altogether, we could increase our food supply by 50 percent! In the real world, complications must enter the equation; even so, reduction of food loss and waste is an area of tremendous potential for feeding the world while healing the environment.

Food Foolish covers a lot of ground, and if you like concrete information densely but attractively presented, you'll be happy. (If you're fond of Oxford commas, you will be less pleased, but their lack is not as obvious when reading as it was to me when typing up the quotations below—and having to backspace again and again to remove the comma that my fingers automatically insert when typing lists.) Yet the authors cannot cover everything, which I remind myself when I consider issues of corruption, abuse of power, and even bloated bureaucracy that keep food from reaching the hungry. As the International Justice Mission has noted, we can provide people with food, skills, books, schools, medical supplies, tools, seeds, and even land, but without honest and functional political and legal systems, they won't be able to hang onto them. Clearly the problems of hunger, resources, and the environment must be tackled on many fronts.

Fixing the global food supply chain requires investment. ... Sometimes the humanitarian return of "doing good" is enough; certainly governments spend simply for the good of their citizens. Other times a true financial return is required to persuade people to act, especially in the private sector. The moment those two returns intersect is a moment of critical mass, when doing good and doing well align, rapidly accelerating innovation and new investment.

There is precedent for this kind of global alignment. In 1993 the U.S. Green Building Council was formed to promote sustainability in building design, construction and operation. At the time, green investment seemed expensive and was misunderstood. "Prior to the U.S. Green Building Council," remembers Rick Fedrizzi, CEO and founding chairman, "Environmental organizations and business lined up against one another. What we did at USGBC was to create a place where business could actually engage one-on-one with environmental and government organizations. By having a voice and a pace at the table, some of the best ideas imaginable have come forward."

...

The global green building movement began as a way to protect the planet and "do the right thing." Today it has become a business imperative that drives real financial return, including significant improvements in tenant occupancy and retention with higher rents and overall building value.

One of the strengths of Food Foolish is its emphasis on positive actions more than blame, and its revelations of the global nature of both the problem and the solutions: everyone has a part to play. Half of all global food loss occurs in Asia, and there's much that can be gained from solving the problem there. But ...

What does food loss look like per person? On a per capita basis, Europe, North America, Oceania and Industrialized Asia waste between 300 and 340 kg of food per year. South and Southeast Asia, despite high absolute waste, have among the smallest per capita at 160 kg. In addition, in medium- and high-income regions, most waste occurs at the end of the supply chain when food is discarded by consumers and retailers. This means that energy inputs such as harvesting, transportation and packaging are embodied in the food. For example, if we must waste a tomato, it's relatively better to have it decompose in the field rather than pick, clean, pack, cook, ship and display it at retail, only to have it thrown out by a consumer.

There are two very different kinds of problems associated with food loss and waste. One is structural in nature: bad weather, poor roads, improper packaging and an inadequately refrigerated distribution system. Many of these issues can be addressed through careful planning, poliitcal will and sufficient investment. And then there are problems taht are economic and cultural in nature, powerful forces almost built into the system. Food too expensive to be purchased will rot in the warehouse. Food too unprofitable to harvest will be lost in the field. Meal servings that are twice what a person can eat will be partially discarded. A perfectly edible apple with harmless spots or a misshapen carrot might be tossed in a landfill if there are cheap and perfect alternatives. The elements of supply and demand, pricing, tradition and culture all play an important role in food loss and waste. Most of all, ... [it is] clear that there are challenges and opportunities enough for the entire global community.

Developing nations can have the greatest impact on food loss, hunger, land use, climate change, and ... freshwater by focusing on upstream improvements—harvest and distribution—in the food supply chain. Developed countries need to emphasize reductions in downstream food waste.

And now for the random quote section you all look forward to. I warn you that it's just a taste of the book and I've left a lot of important stuff out. (More)

Today's Beetle Bailey is for all our Swiss folks:

Permalink | Read 2009 times | Comments (1)

Category Just for Fun: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

Long ago, my friends who are university professors shared their frustration that their students were coming to college woefully under-performing in mathematics—even the math majors. How could they teach the college-level math they were charged to impart to their students, when those students hadn't even grasped the math they were supposed to have learned in high school, or even earlier?

This article shows that non-technical fields have similar problems. (H/T BJT)

When Michael Laser attempted to teach expository writing on the university level, he ran into a major glitch: his students couldn't construct basic, readable sentences.

The teaching of writing has become an academic specialty with its own dominant philosophy, which argues against grammar instruction. But I believe that ignoring awkward writing will prove to be a mistake — an educational fashion that will handicap a generation, until someone shouts, Look at the clumsy writing our students are producing! I’m not saying the current focus on constructing competent arguments is wrong. But many students arrive at college unable to write grammatically correct sentences, and we need to teach them that skill, too.

I commend Laser for his attempts to fill in the huge gaps in his students' educations, but the most important sentence of his essay is this one: Their writing may improve with practice as they make their way through college — but they’ve already been practicing for twelve years!

Bingo. School has swallowed thirteen or more years of these adult children's lives, and disgorged them incompetent in the very basics of reading, writing, and arithmetic. Colleges are wasting very expensive class time attempting to make up the deficit, but according to Laser, success is elusive. Have we managed to inoculate our children against learning? Have they developed a resistance to education over the years, like antibiotic-resistant bacteria?

I can't believe that so many American children have suddenly become stupid; I have to believe that the system is failing them. Yet even if large numbers of children have started to come into the system without basic competencies—and don't forget, the system gets them younger and younger these days, so they haven't had much time to fall—isn't the end result ample evidence that the system has broken down and needs to be changed? If they can't learn to add, why don't we give them calculators and train them to be plumbers, a profession that is necessary, can't be sent overseas, and almost certainly will earn them more money than they're likely to get upon graduating from college still incompetent in basic academics and with a mountain of debt besides?

And yet, attempts to require accountability from our schools are met with extreme resistance, not only from administrators and teachers and unions, but even from parents. The last astonishes me. What I wouldn't have given for a system that provided a clear measure of what my children knew going into a school year and what they knew coming out, coupled with the ability to make educational choices based on that information! In all the kerfuffle over so-called high-stakes testing these days, I see with sorrow that administrators don't have sufficient faith in their teachers, and teachers don't have sufficient faith in themselves, to keep teaching as they've always taught. Tactics such as teaching to the test, repetitive testing, and making a big deal out of the whole thing don't educate children—they only invalidate the results. This is the equivalent of the college-student trick of pulling an all-nighter the day before an exam, and we all know how much education that engenders.

I'm not denying that there is gold that can be mined from the school system, but there is so much dross, and even the brightest kids are losing, especially when you consider their potential. Laser writes,

A few bright students will quickly absorb the new concepts; the others will fill out their worksheets on subject-verb agreement almost perfectly, and then write things like, The conflict between Sammy and Lengel are mainly about teenage rebellion.

Note that the students he calls bright, the ones who picked up on what he taught them, found those basic skills to be new concepts.

Again, let me be clear: I know there are great teachers—our children experienced several of them—and good schools. I know teaching is a very difficult job, one I could not do. (I'm a good tutor with students who want to learn. Give me a whole classroom, however, or a student who doesn't care, and I'd run away, screaming.) But look around: How can a system with such a terrible time-and-effort to effectiveness ratio not be broken? We have taken away the best hours of our children's childhoods, and given them what in return? Proms? Football games? The chance to sit in the same room as their age-mates for hours on end? A few crumbs of learning that should have been acquired in a fraction of the time?

Which of you, if your son asks for bread, will give him a stone?

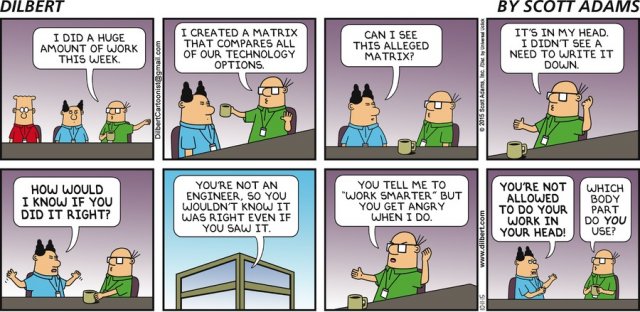

Today's Dilbert is for all the bright students frustrated by teachers who insist that they show their work.

Don't overthink it; I just think the last panel is funny.

I know it's sometimes important to show the intermediate steps, and what I used to tell my students was that they didn't need to show their work, but that if they didn't, they wouldn't get any partial credit if their answer didn't agree with mine. Too many teachers, however, don't understand that some students can no more explain the process by which they arrive at the correct answer to a math problem than a fluent reader can detail the steps by which he understands a paragraph. "Showing your work" becomes a matter of reverse engineering, which is another skill altogether.

I've noticed a strange error in the time stamp when I take videos with my phone. A Google search has not led me to others experiencing the same problem, so I'm posting it here so that the problem will be "out there" in case someone comes along.

The photo and video time stamps seem to be consistent and accurate, until I change time zones. When I do, my phone automatically updates its time to reflect local time, which is exactly what I want it to do. Whatever time stamps my photos apparently grabs the system time, because they show the correct local time. However, the videos do not.

When I shot videos in St. Louis, Missouri, which is on Central Time, their time stamp was still on Eastern Time—one hour ahead. When I took videos in Switzerland, the time stamp acted as if I were still back in the U.S., on Eastern Time: it was six hours behind.

As long as I am aware of the problem, I can easily correct the time because my file naming convention includes the date and time. I just have to remember to add or subtract for the videos, and that's usually easy enough because otherwise they appear out of sequence. That's how the problem came to my attention in the first place.

But what I'm really curious about is why the photos have the correct time and the videos don't. It's the same camera that takes them both. The only logical place for the software to get the time is from the phone's system time. But obviously whatever stamps the videos is doing something altogether different. Well, not altogether: the minutes and seconds are correct. It's just the hour that's wrong, and it's clearly a time zone effect.

If anyone comes by here looking for answers, I don't have them. But at least you'll know that someone else has had the problem. And if anyone comes by with solutions, thanks in advance!

Would you be this cool if you found an eight-foot king cobra under your dryer?

Mike Kennedy's cobra escaped a month ago. Intense efforts on the part of many to find it came up empty.

Last night Cynthia Mullvain was putting clothes in her dryer when she heard a hiss.

Did she panic? Throw a fit? No, but she did call for wildlife officials to come investigate.

They retrieved the missing cobra, which was officially identified by its microchip—not that king cobras are so routinely found in Ocoee, Florida that there was any doubt.

Ms. Mullvain is not suing—someone, anyone, everyone—for pain and distress. She didn't whine to the media about how scared she was, and how no one should have to go through such an experience. She didn't demand that the cobra be killed or not returned to Mr. Kennedy. She's happy to have him go back home, as long as his enclosure is secured.

I think Cynthia Mullvain is one cool lady and reacted just the way a good citizen should have.

Permalink | Read 2198 times | Comments (0)

Category Random Musings: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

This summer I noticed that our grandson was reading a book about "staycations." I think it was about how to have a great vacation but save money by staying in your own town, and your own home, but acting as if you were on vacation: eating out, seeing the attractions that you would see if you were visiting your city as a tourist, etc. However, my mind leapt at a different interpretation of the term: What if I "went on vacation" but never left home?

To me, vacations are not only fun but critically important, being mostly about family, but they are anything but relaxing. I leave behind one set of responsibilities, but take on another, and if grandchildren are a joy that reminds me life is worth living, they don't leave much time for rest. Or for making any progress on my own work, which is always waiting for me when I return. So when Porter planned a three-week "working vacation" to the Northeast to help with construction projects in New Hampshire and to help out his father in Connecticut, I thought, "What a great time for me to take a staycation!" Hard as it was to give up any chance to visit family, this was too good an opportunity to miss. I would be home, but not home, avoiding as much as possible any normal activity or chore that I would not be doing if I were actually away. If it could survive three weeks of my being out of town, it could survive being ignored for that long.

There were exceptions. If we had both been out of town, things like mail, newspaper, lawn/pool care, and feeding the worms would have been taken care of, but it made much more sense to handle them myself. A friend pointed out that I could have hired someone to mow the lawn, but that would have been more stressful than just doing it.

I didn't have a hard-core agenda; this was supposed to be a vacation, after all, a personal retreat, and I wanted to leave it somewhat fluid. But I did have a few goals.

- This seemed like the perfect time to accomplish 95 by 65 Goal #94: Rocket boost photo work (40 hours of work in segments of 1 or more hours, over 2 weeks), since I could work largely without interruption and any hours of the day I chose.

- There are some projects that work a lot better if I can spread them over space and time without worrying about interfering in someone else's life. I wanted to work on some of these.

- I've been battling a tendency toward hoarseness ever since I got the worst laryngitis of my life four years ago, and being alone at home with no outside commitments looked to be my best chance to see what a period of voice rest could do to help.

These were my three big priorities. How did I do? (More)

Permalink | Read 2132 times | Comments (6)

Category Everyday Life: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

The best part of our visit to St. Louis, Missouri this year was without a doubt time spent with living relatives. Yet we also had a great time visiting several dead ones.

A member of our extended family was born in St. Louis, and has roots there going back to the mid-1800's, when her great-grandparents arrived from Ireland. Hereinafter she will be referred to as GrandmaX—not to be confused with the usual Grandma on this blog, that is, me—because it is considered bad form to use the names of living people in online genealogical work. The Catholic Archdiocese of St. Louis has a great online burial search tool, so I knew that several of GrandmaX's family members were buried there. It would be fun to see what we could find.

But first, we stopped at the Old Cathedral, the Basilica of St. Louis, King of France, formerly the Cathedral of Saint Louis. This was the first Catholic cathedral west of the Mississippi (but just barely west; it’s right on the river) and was the only Catholic church in St. Louis until 1845. When all other nearby buildings were demolished for the building of the Gateway Arch, the Old Cathedral was left standing because of its historical significance. (You can click on any photo for a closer look.)

Old Cathedral

Old Cathedral  As seen from the top of the Gateway Arch

As seen from the top of the Gateway Arch

The Cathedral may or may not have been the family’s parish church, but it must in any case have been important to them, as they were at that point a Catholic family. When the family left the Catholic Church I do not know. It might have been because of the divorce of William and Margaret (Donohue) Goodman, GrandmaX's maternal grandparents, though both of them, and also Margaret’s second husband, Joseph A. Murray, and some others of their family, are buried in the Catholic cemetery. At the present time, Catholics who are divorced and remarried without having obtained an annulment are not considered to be "members in good standing," and thus cannot participate in some aspects of church life, but they are allowed to be buried in a Catholic cemetery. I don't know if that was also true in the 19th century. (More)