I'm sorting through the photos from our Gambia trip. During our safari in the Fathala Game Reserve in Senegal, I hastily wrote down the names of the animals so that I could properly identify the pictures. That is, I wrote down what I thought I heard our guide say. Her English was excellent but heavily-accented, and I knew that what I heard could not possibly be right. But I wrote it as I heard it, counting on the Internet to help me after we returned home.

It did. For those of you who are curious,

"Rowland antelope" = roan antelope

"yellowbill asparagus" = yellow-billed oxpecker. I knew it couldn't be "asparagus," but that was the closest I could come.

"red vervet monkey" = "patas monkey." I am certain I heard "red vervet monkey," but I couldn't find any red vervet monkeys by name, although many images showed them as a brownish-red color, even though they are apparently often called green monkeys. Google also suggested red velvet cake, which didn't help. Then I found this Wikipedia article, which suggests this of the patas monkey (which looks very much like what we saw):

The patas monkey (Erythrocebus patas) ... is a ground-dwelling monkey distributed over semi-arid areas of West Africa, and into East Africa. It is the only species classified in the genus Erythrocebus. Recent phylogenetic evidence indicates that it is the closest relative of the vervet monkey (Chlorocebus aethiops), suggesting nomenclatural revision.

So I'm sticking with the name our African guides gave it.

Here are a couple from other parts of our stay:

"nests vled vivas yellow female" = some sort of weaver birds' nests, possibly village weaver, possibly Vieillot's weaver. This was a tough one, from our Janjanbureh trip. Fortunately, birding in the Gambia is a popular tourist activity, so that helped. Which particular weaver "vled" is supposed to represent, I can't guess.

"never die plant heal wound kill snake" = moringa plant. This was tougher than it should have been, because where I saw it, the plant had other plants growing with it, and its own leaves had been mostly stripped off. But finally I'm convinced that this is it, despite there being no mention online to confirm our host's contention that it kills, or even repels, snakes.

The rest I actually heard correctly, though I didn't write down as much as I would have liked to. "Write down" meant changing the file name of the camera image to include the label, not the easiest of ways to take notes, but it's what I had.

The Billion Dollar Spy by David E. Hoffman (Doubleday, 2015)

The Billion Dollar Spy by David E. Hoffman (Doubleday, 2015)

This is not a book I would necessarily have picked up myself, but Porter thought so highly of it that I couldn't resist.

He was right.

There are many, many reasons why the Berlin Wall finally came down and the Cold War ended, as varied as President Reagan's firm stand, internal weaknesses created by Communism, and the influence of the Catholic Church in Poland. The Billion Dollar Spy reveals yet another: Adolf Tolkachev, a Russian engineer who fought the system he loathed with the best weapon he could: giving critical information on Soviet military technology to the country best able to make use of it: the United States. This knowledge was beyond value.

Not that we didn't bungle again and again his attempts to help us. The incompetence of the CIA at certain times in history and its unfathomable paralysis at others had me cringing as I read. And in the end Tolkachev and his mission were brought down by a disgruntled former CIA employee who betrayed him to the KGB.

In the meantime, his work exceeded the CIA's wildest expectations, and the story as Hoffman tells it makes for great reading.

More than 40 years after Porter assisted a University of Rochester professor in the search for gravity waves, predicted by Albert Einstein 100 years ago, evidence of their existence has finally been found.

What are you not giving up on?

Permalink | Read 2253 times | Comments (0)

Category Random Musings: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

I was a Girl Scout in various forms (Brownies on up—no Daisies in those days) for most of my childhood. I've written before about my frustrations then and even more so now, so I'll limit today's comments to cookies.

Yes, it's Girl Scout cookie time again, the only time of the year I really appreciate the organization. Not that I can't get plenty (read, too much) in the way of good cookies outside of the Girl Scouts, but their Thin Mints are unique and have been part of my life as long as I can remember. When the girls were young and living at home, we'd buy a case of Thin Mints every year, stick them in the freezer, and dole them out at the rate of one box per month.

This year we tried something new: in addition to the Thin Mints (now half-case) we bought a box of their Lemonades. Meh. Good but not exceptional, not worth the extra price over lemon Oreos.

After purchasing our cookies this year, I reflected how far the Girls Scouts have come in their salesmanship since I sold the cookies door-to-door for 40 cents a box. (The price is now an order of magnitude higher, and I'm sure there is less in the box. But we still buy them.) Back in the day we had to take orders, then go back some weeks later to deliver the actual cookies. Now, the girls have a booth set up in the fellowship area after church, with piles of boxes of cookies ready-to-hand. You see the merchandise, hand over your money, and walk off with boxes of delicious cookies. I know they must sell so much more that way than by the sight-unseen, place-an-order method.

But wait. Not everyone has gotten with the program. A few days later, three little girls in Girl Scout uniforms rang our doorbell and offered to sell us cookies. I had to explain that we had already bought ours for the year. If they had had the cookies right there with them, I'd have bought another box anyway, just to avoid disappointing them. But they did not. They were stuck in the order-taking days.

We've bought cookies at church, outside the grocery store, and even at Outback Steakhouse. I don't know how troops get permission to set up in these public places, but I find it a happier solution all around. Now that's a Girl Scout innovation I can get behind. Probably the only one...

Permalink | Read 2382 times | Comments (4)

Category Everyday Life: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

The Story of Western Science: From the writings of Aristotle to the Big Bang Theory by Susan Wise Bauer (W. W. Norton, 2015)

The Story of Western Science: From the writings of Aristotle to the Big Bang Theory by Susan Wise Bauer (W. W. Norton, 2015)

I didn't intend to read this book yet. I had put it on my Amazon wish list with the thought that I might receive it for Christmas. I've barely started Bauer's The History of the Renaissance World (95 by 65 goal number 64), which I felt I should finish before starting another of her books. But then our library purchased the book, and I thought it would be a good idea to skim it and make sure I wanted to keep it on my wish list. I quickly became hooked.

(The book I read had a slightly different title, though apparently the same content. According to Bauer, it "was originally published as The Story of Science, but my publisher has now changed the title to The Story of Western Science." Does that mean they expect a sequel about Eastern science?)

In keeping with the pattern Bauer set with her books of history, this is not so much the history of science as the story of science.

It traces the development of great science writing—the essays and books that have most directly affected and changed the course of scientific investigation. It is intended for the interested and intelligent nonspecialist. It shows science to be a very human pursuit: not an infallible guide to truth, but a deeply personal, sometimes flawed, often misleading, frequently brilliant way of understanding the world.

Each part presents a chronological series of "great books" of science, from the most ancient works of Hippocrates, Aristotle, and Plato, all the way up to the modern works of Richard Dawkins, Stephen Jay Gould, James Gleick, and Walter Alvarez. The chapters provide all of the historical, biographical, and technical information you need to understand the books themselves.

Not that it's necessary to read the books themselves. Bauer's chapters can stand alone to provide a solid introduction not only to the development of science, but to the science itself, on an intelligent but non-technical level. For those who want to dig deeper, Bauer's website provides excerpts from the older and less accessible books. Deeper still? She recommends sources for the originals (translations where necessary) in both print and electronic formats.

Most of us are fed science in news reports, interactive graphs, and sound bites. These may give us a fuzzy and incomplete glimpse of the facts involved, but the ongoing science battles of the twenty-first century show that the facts aren't enough. Decisions that affect stem cell research, global warming, the teaching of evolution in elementary schools—these are being made by voters (or, independently, by their theoretical representatives) who don't actually understand why biologists think stem cells are important, or how environmental scientists came to the conclusion that the earth is warming, or what the Big Bang actually is.

Scientists who grapple with biological origins are still affected by Platonic idealism today; Charles Lyell's nineteenth-century geological theories still influence our understanding of human evolution; quantum theory is still wrestling with Francis Bacon's methods.

To interpret science, we have to know something about its past. We have to continually ask not just "What have we discovered?" but also "Why did we look for it?" In no other way can we begin to grasp why we prize, or disregard, scientific knowledge in the way we do; or be able to distinguish between the promises that science can fulfill and those we should receive with some careful skepticism.

Only then will we begin to understand science.

The Story of Western Science is a solid, intellectual work, but not intimidating. I think our twelve-year-old grandson would enjoy it, and lay a solid foundation for further growth. His nine-year-old brother might even get something from reading through it, though both would benefit from rereading it at a later date. So would I—and I have a degree in mathematics and a stronger background in physics than most.

The book is also a pleasure to read because Susan Wise Bauer writes so well. I do object to her persistent use of the term "different than" instead of "different from," which is a pet peeve of mine—but that's easy to forgive for the overall delight her writing brings. I recommend The Story of Western Science wholeheartedly.

Having read it, however, there's no longer any reason to keep it on my Amazon list—unless, of course, for the sake of those aforementioned grandchildren.

I know there are Donald Trump supporters out there. I don't have the right to say much about them, as I don't know any of them, not even on Facebook. I do know some Bernie Sanders supporters, and the passion with which they believe in him. I'm going to go out on a limb, however, angering them all, I'm sure, and say that both camps have much more in common than they will ever believe.

They don't care much about history, economic theory, or diplomacy, and they are each pushing for paths that can take our country down, fast. What they do know is that things are badly wrong, and they're rightfully upset about it. Never mind that they think it's different things that are wrong.

The "anything is better than what we have" mentality really doesn't know—or doesn't believe—how bad things can be. (See above comment about ignorance of history—and of many other present-day cultures for that matter.) All the same, it doesn't do well for any political party to ignore the needs and frustrations of the people until so much pressure builds up that all hope of rationality is gone. This is what gave us the Affordable Care Act instead of a reasonable, workable, affordable approach to health care. (Have I mentioned that the Swiss health care law both works and is only sixty-some pages long? Though even they admit to being dependent on American pharmaceutical innovation that may well be on its way out now.)

Porter found this article that explains Donald Trump's popularity, and importance, better than anything I've seen yet: "Donald Trump is Shocking, Vulgar, and Right: And, my dear fellow Republicans, he's all your fault.

Consider the conservative nonprofit establishment, which seems to employ most right-of-center adults in Washington. Over the past 40 years, how much donated money have all those think tanks and foundations consumed? ... Has America become more conservative over that same period? Come on. Most of that cash went to self-perpetuation. ... Pretty embarrassing. And yet they’re not embarrassed.

Conservative voters are being scolded for supporting a candidate they consider conservative because it would be bad for conservatism? And by the way, the people doing the scolding? They’re the ones who’ve been advocating for open borders, and nation-building in countries whose populations hate us, and trade deals that eliminated jobs while enriching their donors, all while implicitly mocking the base for its worries about abortion and gay marriage and the pace of demographic change. Now they’re telling their voters to shut up and obey, and if they don’t, they’re liberal.

On immigration policy, party elders were caught completely by surprise. Even canny operators like Ted Cruz didn’t appreciate the depth of voter anger on the subject. And why would they? If you live in an affluent ZIP code, it’s hard to see a downside to mass low-wage immigration. Your kids don’t go to public school. You don’t take the bus or use the emergency room for health care. No immigrant is competing for your job. (The day Hondurans start getting hired as green energy lobbyists is the day my neighbors become nativists.) Plus, you get cheap servants, and get to feel welcoming and virtuous while paying them less per hour than your kids make at a summer job on Nantucket. It’s all good.

When was the last time you stopped yourself from saying something you believed to be true for fear of being punished or criticized for saying it? If you live in America, it probably hasn’t been long. That’s not just a talking point about political correctness. It’s the central problem with our national conversation, the main reason our debates are so stilted and useless. You can’t fix a problem if you don’t have the words to describe it. You can’t even think about it clearly.

This depressing fact made Trump’s political career. In a country where almost everyone in public life lies reflexively, it’s thrilling to hear someone say what he really thinks, even if you believe he’s wrong. It’s especially exciting when you suspect he’s right.

Now if only someone will do the same thing for the Democrats and Bernie Sanders.

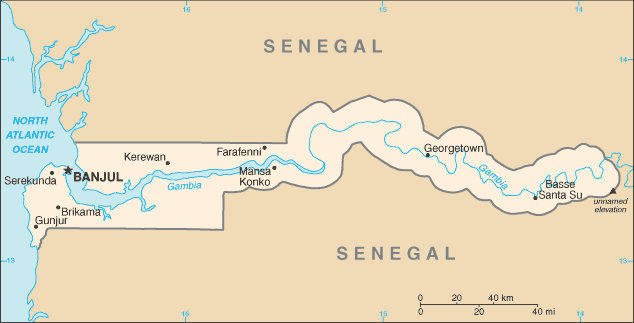

Many of you know that we recently returned from a two-week trip to the Gambia, that tiny country within Senegal in West Africa. Since I never fully appreciate an experience until I've written about it, I've started a new category here, in which I'll put both travel memories and Gambia-inspired musings. Expect it to be rather random; if I wait to get it all organized I'll have forgotten too much. (Lots of thinking to do, many activities, and over 1600 photos.) In the meantime, here's some background.

After a couple of false starts some 45 years ago, I finally found a college roommate who became a friend for life. (Realize that in those dark ages, even smokers and non-smokers were often paired up to live together!) Kathy went on to get a Ph.D. in mathematics and enjoy a long career as a university professor with a well-deserved reputation as an excellent and caring teacher. Several years ago she embarked on a different sort of adventure altogether, and is now a math professor (and department chair) at the University of the Gambia, with an even stronger reputation for both excellence and caring. She's not there for the adventure (although there is plenty of that), nor for the salary (meagre), and certainly not for the working conditions, but to make a difference in the world. Yes, she's a saint, a fact of which I'm all the more convinced since our visit. (You can ignore this part, Kathy, assuming your flaky Internet connection lets you see it. You and I both know you're still the crazy person I knew back in college.) Perhaps it's more useful—since labelling people as saints tends to put them out of reach—to say that she's a Christian called by God to use her skills and experience in an unusual place. However you look at it, she's there, and is making a difference. The world, Africa, the Gambia, even the University—these are too large to exhibit visible change. But without a doubt she has for a number of years been changing the lives of families and individuals for the better.

However, despite the University's state of denial, she won't be in the Gambia forever. Hence our determination to seize the year (and the presence of this trip on my 95 by 65 list). The only reasonable time to make the trip was in January, which is during the dry season and between semesters for Kathy. Coming during the dry season turns out to be very, very important: the weather, though still hot (90's) is much more pleasant, the mosquitos are much less numerous, and transportation tends to be through a few inches of dust instead of a foot or more of garbage-and-water. Definitely the time to go!

So we went.

Some people travel for adventure. Others for the educational and cultural growth. As much as I value the latter, the primary importance of travel for me is still being with family and friends—and specifically, seeing them in their native habitat, as it were, so that their stories and experiences have more meaning when I hear them from far away. The educational experiences are a great bonus thrown in, and on this trip we even had a few adventures.

Stay tuned.

I wrote this in response to someone's Facebook discussion, and put too much time into it not to save it here. The subject was the very survival of America, and one optimist had said, "Doom and gloom speak just because the candidates of your choice aren't winning. People have been saying for over 200 years that the country is doomed if so and so gets elected to office. Well the country is still here and alive and well." This was my response:

It is true that of the presidents I have experienced, the ones I thought were good people (Carter, Bush II) turned out to be terrible presidents, and the ones I thought were nuts (Reagan, Clinton) turned out much better than I could have imagined. Sometimes good intentions aren't enough, and sometimes people rise to the office. And good and bad luck have more effect than we admit.

Our recent trip to the Gambia convinced me that the best equipment in the world will not survive ignorance, abuse, and lack of regular maintenance. I worry not only for the United States, but for all of Western Civilization. It is under attack from all sides, from the Terrorists Formerly Known as ISIS to American college campuses. We whose mighty heritage this is have not done well in keeping it clean and oiled. Instead of fixing the broken parts, we trash them. Our children have no idea how to keep this great gift of the ages in working order. The beliefs that massive debt (personal and national) is okay; that name-calling is rational discourse; that our own failures are actually someone else's fault; that success implies not hard work but ill-gotten gains; that poor, even immoral, choices should not have consequences; that those who disagree with us are somehow subhuman and deserve whatever we can heap upon them—these attitudes, much more than whoever gains the highest office, are what will bring us down.

Sure, there are still pockets of resistance, but they're getting smaller and weaker. There's still hope—but only, I think, if we realize, as the great Pogo once said, "We have met the enemy and he is us."

I had a 325-day streak going on my DuoLingo language lessons. I managed to maintain it through our long plane flight to the Gambia, and through the first couple of days there, even though Internet was spotty and difficult. But then we went on a five-day trip up-country where there was No. Internet. At. All. Nada.

DuoLingo allows you to "buy" (with credits) a "streak freeze" by which you can suspend your streak and restart. That's the theory, anyway. However, you can only buy such an extension one day at a time, so even though I have so many credits I could suspend for 137 days, that did me no good at all when I couldn't access the Internet for several days in a row.

I'm okay with all this, though I wish DuoLingo had a more useful "suspend" function. Streaks can be motivating, and the daily reminders certainly helped me establish a good habit. But while striving to keep up a streak can be a good servant, it's a bad master, and I threw it away without a second thought in favor of an invaluable experience.

My walking/running habit suffered a similar setback this trip. Travel is great, but very hard on carefully, painstakingly built habits. I gave myself four days of recovery once we returned, and there is still much that needs to be done before I can say we're settled back in. But today is the deadline I've given myself for restarting my DuoLingo, exercise, and some other formerly-regular habits. It's a small step, but if I succeed, it will be the soonest I've ever recovered from a trip.

The burden of important projects that have been neglected since before Thanksgiving (many of them for much longer than that) is likewise weighing heavily on me. Travel is fun, and more importantly travel is valuable—ten times more so when it means spending time with family and friends. But if I'm going to continue to enjoy it, I need to be more deliberate in budgeting for project time when we are home.

Plus, for me, the larger part of the travel iceberg lies below the surface: the processing and writing time. Not to mention over 1600 photos to sort, evaluate, and organize.

Ganbarimasu!

On January 28, 2016, we were preparing to land at the end of our flight across the Atlantic from Paris to Newark, the penultimate leg of a journey home from the Gambia that had begun with a take-off from the emergency Space Shuttle landing site that serves as the Banjul Airport runway.

Thirty years ago, that same Atlantic received the shredded remains of the Challenger and all her crew.

What Reagan (and Noonan) knew, as did Winston Churchill, was how to inspire people to be better than themselves. You don't make children learn more by telling them how stupid they are; you don't make people love others better by insisting they are racist, sexist pigs; you don't encourage the weak to become strong by pointing out their failures.

Nor do you regale them with how strong and smart they are, and insist "you can be anything you want to be." You don't imply that success should be easy or that love doesn't require sacrifice. You don't suggest that the best way to fight terrorism is to continue buying and selling as usual (President Bush after 9/11) or partying on (some Parisians after the recent attacks).

A good leader is not afraid to insist that there is no gain without risk, no success without effort, and no victory without battle. The way is hard, the road is long, and it is not safe. A great leader goes on to encourage others to believe that they are the kind of people who will rise to meet the challenges; that the benefits will be worth the cost; and that the way, though difficult, will be sprinkled with joy.

Permalink | Read 3287 times | Comments (0)

Category Education: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Travels: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Random Musings: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Everyday Life: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] The Gambia: [next] [newest]

I made a discovery last week: I don't fully experience an event until I've had time to process it—ideally, to write about it.

When I'm preparing for a trip, people say, "You must be so excited to [fill in the blank]." But I almost never am. Doing something is rarely exciting; having done something is what thrills me. I've always thought this to be weird, and even felt guilty about it. How crazy is it to appreciate an experience—even one I really enjoy—only when it's over?

The revelation I had last week is that it's all a matter of processing. Experiences bring a flood of sensory information that needs to be dealt with, and if I don't have that opportunity, the pressure builds up like a bad case of indigestion. This is why, for example, when I'm away from home for an extended baby-birth visit, I will sacrifice an hour or two of much-needed sleep to write a blog post. If I don't, more often than not my mind will rebel and not let me sleep anyway.

When I write about an event—even if the writing doesn't actually take physical form, though that's best—the experience coalesces into something coherent and memorable. That's when it becomes real.

Permalink | Read 2598 times | Comments (1)

Category Random Musings: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

This news ought to be making major headlines: Surgery is not necessarily the best treatment for appendicitis! Granted, the alternative is a heavy course of antibiotics, which also carries risks, but I'd take that over surgery any day. (Just don't forget to eat your yoghurt.)

Ultimately, 102 enrolled in the study. Of those, 37 families chose to have their children treated with at least 24 hours of intravenous antibiotics followed by 10 days of oral antibiotics. The others elected surgery.

A year later, about 76 percent of kids whose family chose antibiotics were still healthy and didn't need additional treatment.

Compared to those who got surgery, the children who got antibiotics also ended up needing an average of 13 fewer days of rest, and had medical bills that were an average of $800 lower.

There was also no significant difference in the number of appendicitis cases that became complicated during surgery or after treatment with antibiotics. Minneci said that shows the treatment options are similar in terms of safety.

The option of antibiotics for simple appendicitis is likely already available in large medical centers for adults with appendicitis and probably a few large centers that treat children, said Jennings, who wasn't involved in the new study.

Minneci said his hospital already offers the option of antibiotics to people with simple cases of appendicitis, and he expects other hospitals to start developing protocols to introduce the option, too.

"I think if a family walks in the ER now and they bring it up, the surgeon should discuss it with them because it’s a reasonable option," he said.

Is it right for a Christian to carry a gun? Or even own one at all?

I'm not here to debate pacifism. For centuries, even millennia, there have been debates both among Christians and in general society over the legitimacy of war and even self-defense. I can't settle that here.

Nor, despite the subject, is this about gun control, gun safety, or the Second Amendment. It's about something much more important.

What I want to address is an idea currently making the rounds in the Christian community: that a Christian who buys a gun to protect his family is proclaiming his lack of faith. That he doesn't trust God to take care of him and the people he loves.

Such a statement is absolute nonsense.

I've heard that logic before. I wonder how many of those who loudly proclaim that buying a gun means you don't trust God for your safety would agree with the following similar claims:

- People who use birth control don't trust God to determine the size of their families and provide for them.

- People who use doctors/hospitals/medications aren't trusting God to take care of their health.

I acknowledge that certain elements behind those ideas ring true. There is in modern society what I'd call a "birth control mentality" that I believe has done great harm (blog post on that to come eventually, I hope), and blind trust in medicine has done its share of damage, too. But the above statements, as they stand, are dangerous nonsense, and so is the same logic applied to guns.

God gives us resources, and the ability to develop and use tools. It is our responsibility to use the tools wisely. Embracing them uncritically and rejecting them out of hand are both extremes that risk insulting the Giver. Even worse than insulting God (he's already handled more than we could possibly dish out), is belittling the faith of those who don't share our opinions. "To his own master he stands or falls."

Permalink | Read 2243 times | Comments (4)

Category Random Musings: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

One of my favorite Christmas presents this year was this butter dish.

I received many wonderful gifts for Christmas, and point of this post is not to minimize any of them, but to highlight something important about gift-giving.

This butter dish actually fails several of the tests of what is usually considered a good gift.

It's inexpensive. That's not to say the giver was cheap, as this was only part of my Christmas present, but even had it stood alone it would have been a welcome gift. Sometimes the monetary value of a gift does indeed matter; sometimes it's important to hear from someone we love, "you are more important to me than a giant TV." But more often than not, the true value of an item is surprisingly price-independent.

It's practical. Actually, that's a plus for me, though some people scoff at useful gifts.

It was something I'd asked for. I can't shake the idea that the best presents are those that flow from the heart of a person who knows you well enough to see a need or a desire and present it to you as a gift, especially if it's something you can't or won't buy for yourself. Sometimes that still happens, but these days we most often don't know each other well enough, because our lives are so scattered.

I could have bought it myself. Let's be honest: if it's something we want that's affordable, most of us just buy it ourselves rather than hope someone gets it for us at the next appropriate occasion.

Why am I so excited about this butter dish? Because it was perfect. It was just what I wanted and had gone without for a long time. I have two butter dishes that are exactly like this in all but color—and the fact that the tabs on the ends broke off long ago, rendering them frustrating to use. I'd looked for replacements on and off for years, and what I found was too fancy, too expensive, too ugly, or otherwise just not right. Finally, this one showed up in an Amazon search one day. It was close to Christmas so I put it on my wish list, and at Christmas my hope was realized. This morning, as I unloaded it from the dishwasher and put it in its place, looked at that modest butter dish and felt a thrill of delight.

That's what we hope all our gifts will do.

Permalink | Read 2356 times | Comments (0)

Category Everyday Life: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

2015 turned out to be a good year for reading: I set a new record (since I begain to keep track in 2010): 72 books, on average six books per month. The smallest number of books read per month was two, which occurred in both June and August; between those two months, July had the most: eleven. By some standards that's not a lot of reading, but it's a good deal more than I was accomplishing before I made reading a priority, and started measuring.

Here's the list, sorted alphabetically. A chronological listing, with rankings, warnings, and review links, is here. It's a good mixture of fiction, non-fiction, and poetry; old books and new; short books and tomes. I enjoyed most of them, and regret none.Titles in bold I found particularly worthwhile.

- 1066 and All That by W. C. Sellar and R. J. Yeatman

- Artemis Fowl (Book 1) by Eoin Colfer

- Artemis Fowl (Book 2): The Arctic Incident by Eoin Colfer

- Artemis Fowl (Book 3): The Eternity Code by Eoin Colfer

- Artemis Fowl (Book 4): The Opal Deception by Eoin Colfer

- The Bible

- The Billion Dollar Spy by David E. Hoffman

- The Black Star of Kingston by S.D. Smith

- A Book of Strife, in the Form of the Diary of an Old Soul by George MacDonald

- The Call of the Wild by Jack London

- A Child's Garden of Verses by Robert Louis Stevenson

- A Christmas Carol by Charles Dickens

- Better than Before by Gretchen Rubin

- England's Antiphon by George MacDonald

- Exotics by George MacDonald

- Food Foolish by John M. Mandyck and Eric B. Schultz

- Forty Ways to Look at Winston Churchill by Gretchen Rubin

- The Gambia in Depth by the Peace Corps

- Gifted Hands: The Ben Carson Story by Ben Carson with Cecil Murphey

- The Green Ember by S.D. Smith

- Gutta-Percha Willie by George MacDonald

- It All Started with Columbus by Richard Armour

- Jesus Through Middle Eastern Eyes by Kenneth E. Bailey

- The Jungle Book by Rudyard Kipling

- The Kids from Nowhere by George Guthridge

- Legally Kidnapped by Carlos Morales

- Life of Fred: Goldfish by Stanley F. Schmidt

- Life of Fred: Honey by Stanley F. Schmidt

- Life of Fred: Ice Cream by Stanley F. Schmidt

- Life of Fred: Jelly Beans by Stanley F. Schmidt

- Life of Fred: Kidneys by Stanley F. Schmidt

- Life of Fred: Liver by Stanley F. Schmidt

- Life of Fred: Mineshaft by Stanley F. Schmidt

- Life of Fred: Pre-Algebra with Biology by Stanley F. Schmidt

- Love Does by Bob Goff

- Malcolm by George MacDonald (much Scottish dialect)

- Malestrom by Carolyn Custis James

- Manjiro by Hisakazu Kaneko

- The Mark of the Dragonfly by Jaleigh Johnson

- The Marquis of Lossie by George MacDonald (some Scottish dialect)

- The Martian by Andy Weir

- Mary Marston by George MacDonald

- The Mind's Eye by Oliver Sacks

- Old Peter's Russian Tales by Arthur Ransome

- Paul Faber, Surgeon by George MacDonald

- The Penderwicks at Point Mouette by Jeanne Birdsall

- The Penderwicks by Jeanne Birdsall

- The Penderwicks in Spring by Jeanne Birdsall

- The Penderwicks on Gardam Street by Jeanne Birdsall

- Pioneer Days by Laura Ingalls Wilder, annotations by Pamela Smith Hill

- The Princess and Curdie by George MacDonald

- The Princess and the Goblin by George MacDonald

- The Qur'an translation by M. A. S. Abdel Haleem

- St. George and St. Michael by George MacDonald

- The Second Jungle Book by Rudyard Kipling

- The SHARP Solution by Heidi Hanna

- Sidney Chambers and the Shadow of Death by James Runcie

- The Six Fingers of Time and Other Stores from Galaxy Magazine

- Sir Gibbie by George MacDonald

- The Story of Western Science by Susan Wise Bauer

- Stiff by Mary Roach

- Thomas Wingfold, Curate by George MacDonald

- To Kill a Mockingbird by Harper Lee

- Tremendous Trifles by G. K. Chesterton

- The Upside of Stress by Kelly McGonigal

- The Village on the Edge of the World by A.T. Oram

- Warlock o' Glenwarlock by George MacDonald

- Weathermakers to the World by Eric B. Schultz

- West Africa Is My Back Yard: Ex-Pat Life in The Gambia and Beyond (Part I: Where on Earth is The Gambia Anyway?) by Mark Williams

- Wilfred Cumbermede by George MacDonald

- The Winged Watchman by Hilda van Stockum

- The Wise Woman by George MacDonald