DragonBox is just one of the reasons I feel myself being dragged inevitably toward the tablet world. My reaction upon seeing my first tablet was that it was too big to be a phone but too limited to be a computer. How can it be a real computer with what passes for a keyboard on a tablet? Or without all my favorite software? Who would want one? But that's where all the cool new software is. :(

Stop the presses! The GeekDad article doesn't mention it, but DragonBox is now available for Windows! (Linux coming soon, they say.) And for only six dollars. (Twice the price of the iOS and Android versions, but there's more to it.) I already know algebra, but it's tempting to check it out.

I've been saying for years that educational software producers need to get together with gaming experts. The potential for computer-aided learning is enormous, but most games are not written for their potential to educate and enighten, and most educational software is barely beyond the flash-cards-with-glitz stage. Not that Joseph doesn't love my PowerPoints, of course. :)

Jean-Baptiste Huynh is a Vietnamese Frenchman living in Norway, who taught math for several years and was frustrated with the way math is taught in schools. He wanted his kids to learn algebra in a way that made sense to them, and with tablets and gamification of education he thought that there must be some way to create an app that would make algebra easier to learn. So he started up a company called We Want to Know, aimed at creating some user-friendly educational games that are (1) really educational and (2) really games. If DragonBox is any indication, he’s on the right path so far.

[Huynh] sees tablet computers as a truly disruptive technology that can change the way we teach and learn.

Thanks to DSTB for the tip. I can't wait to see what's next.

A comment made by Janet to my Quick Tourist's Conversion between Fahrenheit and Celsius post inspired these thoughts, and it seemed better to give them their own post rather than to comment on that one.:

The Orlando Sentinel of January 31 contained an article by a pediatrician, highlighting the efforts of those in his field to combat illiteracy. It included the following sentence:

One in four children grow up without learning how to read.

I have grave doubts about that statistic. If true, there should be rioting in the streets on behalf of the 25 percent, who, under our compulsory education system, have wasted at least ten of the most important years of their lives in school. True, there are a few (very few) children who have handicaps that keep them from learning to read, but there is absolutely no excuse for confining children for most of their young lives if they can't read when they come out. As certain as I am that the institution of school has serious problems, I simply don't believe that it can be doing that badly.

On the other hand, true literacy is more than the mere ability to read words on a page. Understanding, and the ability to reason, are necessary for making sense of writing. That we fail one in four school children that way is still unbelievable, but reading comments written to news websites and blogs (especially those where the subject is political, or controversial in any way) has made it a more credible failing.

I can't get out of my mind the question someone, alas long forgotten, once asked: Is there any material difference between someone who can't read and someone who doesn't? It's not surprising that the mantra among teachers and parents has long been, "I don't care what they read as long as they're reading." But comprehension and logic are skills that must be honed with practice. To that end, what we read is critical: Garbage in, garbage out.

Once upon a time, we gave normal baby shower presents, like everyone else. You know, crib sheets and diapers and cute little outfits.... As time went on, and as we became more experienced parents, we began to change: we started giving books. I suppose a copy of Dr. Spock would have been considered a normal gift, but the books we gave were different, the kind that most people might never run into. They were chosen from a mental list of books, accumulated over the years, which we had found to be especially helpful in the adventure of childrearing. I had quickly become fed up with all the popular parenting books, which seemed to be describing ... well, I don't know who they were describing, but it certainly wasn't our children. These books, taken in toto, did a much better job of understanding the little ones in our care, and of addressing our own particular needs and concerns. I hoped by the shower gifts to spare other parents my own long and confusing journey. This was pre-Internet, remember, and information was harder to come by than anyone born after 1975 can fully imagine.

After a while we learned to be more cautious in our giving, as we discovered that not every new parent is excited about getting books, let alone ones that are ... odd. But I kept the list, calling it The Things Dr. Spock Won't Tell You; over the years, it grew and changed a bit in content, though not in philosophy.

The version I'm publishing now is old, having not been updated since 2005. There are other good books I should add, and perhaps one day I will. It should probably get a new title, too: Does anyone read Dr. Spock anymore? But it is what it is, and I'm only posting it because (1) the blog is a good place to tuck away old writings, and (2) I want to reference it in a later post.

One thing that will become obvious to anyone who reads the books is that they contradict each other in places. So what? I don't agree with everything in any of them; the path of truth is strewn with paradox. The point was never to push any particular view of childrearing, but that in each book we'd found something of great value. Take what is useful, and leave what is not.

Despite their differences, these books tend to have two things in common that undergird our own childrearing philosophy. One is a great respect for children, and a conviction that we as a society have underestimated them in many areas, from the physical to the intellectual to the spiritual. The other is a great respect for parents, the belief that "an ounce of parent is worth a pound of expert." (More)

Mea culpa! It's been nearly a year since my post about Stephan's Dots book (numbers in four languages), and I never did update it with Joseph's response. It was an immediate hit, and is still one of Joseph's very favorite books.

Here are a few videos showing Joseph and the book in action:

The book has proved very durable under heavy use, and if the $70 cost seems extravagant, I'd say Joseph has definitely gotten his parents' money's worth already.

Update 10/16/19: As has happened with several old posts containing videos, I'm pretty sure a chunck of the post between the video and the final sentence was accidentally removed in the process that switched the videos from Flash to <iframe>. Someday I may try to recover them ... but realistically, probably not.

Permalink | Read 2940 times | Comments (4)

Category Reviews: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Education: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Children & Family Issues: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Everyday Life: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

My backblog has once again achieved unmanageable proportions, so it's time to bring back—ta da!—Casting the Net, in which I collect related—or unrelated—snippets of items that have caught my attention. Today's post was inspired by a series of videos on math education in the U. S. sent to me by my sister-in-law. (Um, back in March 2011; I told you I'm behind.)

First, Math Education: An Inconvenient Truth, by M. J. McDermott, who is neither a teacher nor a mathematician, but with a degree in atmospheric sciences it's safe to say she has a pretty good grip on the kind of math elementary and secondary school students should be learning. And she doesn't like what she sees being taught in schools today, in particular the approaches of Investigations in Number, Data, and Space (aka TERC) and Everyday Mathematics. (duration 15:27)

Stone Soup today is worth highlighting.

Sporcle, my favorite technique for developing mental "hooks" on which to hang related information, now has a game for the Swiss cantons! I still need to work on them, but I'm pretty happy to have gotten 20/26 on my first try—without looking at the Swiss map (thank you A&M!) on my wall. All but one missed canton are in the eastern part of the country, with which I'm less familiar. I am somewhat embarrassed at having missed Neuchâtel, but I still did better that I would do with Florida's counties....

There's also a quiz for Facts about Switzerland, on which I got 37 out of 50 on the first try. I would have gotten two more had I not been interrupted twice in the middle of the game. When will Porter learn not to interrupt when I am doing important work? I also wasted too much time trying variations on "Confederation Helvetica" for the official name.... And their answer for the "Southern Mountain Range" is nitpicking, I think. I'll never be able to remember the name of the president (Eveline Widmer-Schlumpf), but that changes every year, anyway.

Skip this post if you are tired of reading about our fabulous grandchildren. :)

I was talking with Janet the other day, and as I usually do, I asked what new cute things our grandkids were doing.

"Well," she replied, "Joseph counted nearly to 50."

This puzzled me, as numbers are his passion and a month ago he had happily counted past 150 for me.

Then she added, "in Japanese."

"[W]hen I began this article I was dead set against homeschooling, as are many certified teachers. But, after doing research, I’m not so sure."

It's not the most ringing of endorsements, but it represents a big step, and Susan Schaefer's Homeschooling Goes Mainstream and Here's Why is postive about homeschooling from beginning to end.

I learned that homeschooling is way more organized than I thought and very in vogue at the moment. In 1980, home schooling was illegal in 30 states. Now, it is legal in all 50 states with about 1.5-2 million children being homeschooled in the U.S., roughly 3 percent of school-age children nationwide.

This reminder of how far we've come gives me hope for the cantons of Switzerland where homeschooling is still illegal. I pray they'll make progress a bit faster than we did, however—Joseph gets nearer to compulsory school age with every passing hour.

[T]he stigma associated with homeschooling is gone as it becomes more and more mainstream.

I thought the stigma was ancient history, although maybe that's because I rarely pay much attention to such things. Our kids would know better.

The image of homeschooled children spending their days sitting at the kitchen table are long gone. Today’s homeschooled are out and about with many museums offering programs to homeschoolers as well as other hands-on activities, such as nature centers. There are endless websites dedicated to non-traditional learning opportunities in addition to websites offering support and resources for homeschooling families.

Hmmm. Our kitchen table was dedicated to eating, not schooling, though I can't deny that a lot of education happened during dinner. We certainly did our share of out-and-about! All those "endless websites" would have been nice, though. Hard as it is to believe, children, this was Before The Internet, though we did have the Education Round Table on GEnie.

According to the Homeschool Progress Report 2009: Academic Achievement and Demographics, homeschoolers, on average, scored 37 percentile points above their public school counterparts on standardized achievement tests.

Nothing new here, but it is nice to know that the advantage still holds as the homeschooling numbers have grown from "the few, the proud."

[H]omeschooled kids are far from isolated from peers, do well in social situations, and are more likely to be involved in their community. The education level of the parents had little effect on the success of their children, as did state regulations, gender of the student, or how much parents spent on education.

Again, nothing new. In fact, there is little new in the article, but it was still encouraging to read. If there's one thing I've learned in my more-than-half-century of life, it's that what's well known needs to be said again and again to each new generation, each new situation, each new demographic, or it is in danger of being lost.

What caught my eye about this article, above and beyond the homeschooling connection, was the paper in which it appeared: The Middletown (Connecticut) Patch. I thought the format and logo looked familiar, and indeed it was the obviously-related East Haddam-Killingworth Patch of a year ago April that mentioned my research on Phoebe's Quilt. So it must be an important journal, right?

Until June of 2010, homeschooling was legal in Sweden, albeit within some onerous regulations. But with the passage of a comprehensive revision of the education system, the right of parents to direct the education of their own children has been virtually abolished, in apparent violation of the European Convention on Human Rights, Protocol 1, Article 2:

No person shall be denied the right to education. In the exercise of any functions which it assumes in relation to education and to teaching, the State shall respect the right of parents to ensure such education and teaching in conformity with their own religions and philosophical convictions.

If you want to become depressed learn more, there are many stories, often heart-wrenching, at the Home School Legal Defense Association site. (I may have some quarrels with the HSLDA's approach, left over from the early days of homeschooling, but that doesn't negate their importance as a source of homeschooling advocacy and information.)

As part of an effort to raise awareness of their plight, Swedish homeschoolers are staging a Walk to Freedom from Askö, Sweden to the Finnish island of Åland, to which many Swedish homeschooling refugee families have fled. (No, they're not walking on water, but plan to secure the help of a ferry for the last leg.) Their adventure begins tomorrow.

I have so many things to write about, but am feeling a time crunch at the moment. Just so you know I haven't forgotten you altogether, you get someone else's comments on homeschooling, in the form of a First Things article by Sally Thomas. (H/T Conversion Diary). Warning: it may be a little intimidating if you happen to be feeling a bit insecure about your own homeschooling days. But it's worth reading for the inspiration.

In recent years, as homeschooling has moved closer to the mainstream, much has been said about the successes of homeschooled children, especially regarding their statistically superior performance on standardized tests and the attractiveness of their transcripts and portfolios to college-admissions boards. Less, I think, has been said about how and why these successes happen. The fact is that homeschooling is an efficient way to teach and learn. It's time-effective, in that a homeschooled child, working independently or one-on-one with a parent or an older sibling, can get through more work or master a concept more quickly than a child who's one of twenty-five in a classroom.

To my mind, however, homeschooling's greatest efficiency lies in its capacity for a rightly ordered life. A child in school almost inevitably has a separate existence, a “school life,” that too easily weakens parental authority and values and that also encourages an artificial boundary between learning and everything else. Children come home exhausted from a day at school—and for a child with working parents, that day can be twelve hours long—and the last thing they want is to pick up a book or have a conversation. Television and video games demand relatively little, and they seem a blessed departure from what the children have been doing all day.

At home we can do what's nearly impossible in a school setting: We can weave learning into the fabric of our family life, so that the lines between “learning” and “everything else” have largely ceased to exist. The older children do a daily schedule of what I call sit-down work: math lessons, English and foreign-language exercises, and readings for history and science. The nine-year-old does roughly two hours of sit-down work a day, while the twelve-year-old spends three to four hours. But those hours hardly constitute the sum total of their education.

[W]hat looks like not that much on the daily surface of things proves in the living to be something greater than the schedule on the page suggests, a life in which English and math and science and history, contemplation and discussion and action, faith and learning, are not compartmentalized entities but elements in an integrated whole.

I've been experimenting with Memrise for several days—long enough to conclude it merits a mention.

Memrise is a vocabulary review system that specializes in languages, of which there are an incredible number, from French to Quechua to Klingon! (Alas, no Swiss German, no doubt hampered by the lack of an official written form.) There are other subjects, as well, but not many yet, and they are not well developed. The Periodic Table course, for example, would do better not reversing the "o" and the "u" in fluorine, and settling on either of the two acceptable spellings of the element Al, instead of compromising with "Alumnium." (Or is that a new element, named after all college graduates?)

I'm loving the Introductory German! My favorite language course is still Pimsleur, which along with Hippo gets the correct sound and feel of the language and its structure into my brain. But I also need a way to build up vocabulary, and Memrise is the best I've found so far. The vehicle is a simple "garden" system: new words are seeds, and through practice you sprout them, help them grow, "harvest" (more like transplant) them to long-term memory, and water them to keep them healthy. E-mail reminders bring you back to your "garden" at varying intervals—short for recently-learned words, longer for ones you know better—so you don't lose what you've learned.

It's easy to use and kind of fun. I find that I'm picking up vocabulary pretty well so far, though I do wonder who decided which words to introduce first. I mean, die Bundesrepublik? "Federal Republic" is not exactly a term I use every day. Or how about der Mülleimer? Dustbin? Dustbin? Dustbins are things people in the English novels I love to read are always "tipping" things into, but I'm sure I've used the term fewer times than Federal Republic. And is blöd (stupid) really an essential vocabulary word? Still, in addition to these oddities there are more useful terms, such as das Haus (house), vielleicht (maybe), and der Name (name). And I've finally caught the difference between der Staat (state) and die Stadt (city).

Unfortunately, I can't make the audio work in Firefox, and so must use IE or Chrome if I want to hear the words pronounced. That's something I find very valuable, not only for understanding and speaking, but because having heard the sound of a noun I'm much more likely to be able to remember whether it's die, der, or das, something I always have trouble with. I'm beginning to think of the article and the word as one entity, which of course will get me into trouble when I have to worry about inflection, but I'll climb that hill when I get to it.

It's also German German, and so uses the Eszett instead of the Swiss double "s." However, it accepts the double "s" when I have to type in an answer, so I'm fine with it. Letters with an umlaut are easy to enter, via either a mouse click or the Windows U.S. International keyboard (which I prefer because it is faster).

Here's hoping I manage to stick with the program, and not lose everything when I go on vacation....

Florida gets all too much press for crazy happenings, so it's about time another state took the spotlight. Was it another school shooting that put Cascade High School in Hendricks County, Indiana, in the headlines? Nope. The newsworthy offense was a senior prank involving the deadly ... Post-It note! (H/T Free-Range Kids) Actually, the offense was on the part of the school administrators, who so far have suspended over 50 students, either for participating in the prank or for protesting the school's draconian response.

For years, MIT and Caltech have known that inventive, harmless pranks are a sign of an intelligent, creative student body. I think we can guess what schools the administrators did NOT graduate from—though maybe the helpful janitor (Frazz?) did.

Celebrating a Simple Life has a perceptive post this morning. Ostensibly, it's about giving meaningful praise to children's artwork, but I say her wisdom has a much wider application, for chldren and adults in all areas of life. Read the whole thing; it's worthwhile, it's short, and it shows a great picture painted by her son.

When you give meaningless praise, your kid comes to expect it for every not-so-impressive act they perform. It's exhausting to the parent, becomes meaningless to the child, and sets up a bad habit of being forced to praise mediocrity, with your child knowing full well that the praise is hollow.

When you describe what you see, you are telling the child your work is worth examining more closely. You are encouraging language development through your description. You are teaching your child to have a critical eye for their own work. And then when you do offer praise, your kid knows they deserved it.

(Apologies, to those who care, for publishing the awkward gender-neutral but grammar-offensive language. The content is worth getting past that.)

I'm convinced that non-specific praise in any area, for child or adult, usually does more harm than good. It means we're not taking them or their work seriously. It means we're too lazy (tired, busy, etc.) to do our own job right. And it sets up children, especially, for failure in the long run: when praise is unrelated to the quality of the work, how can they improve? When a five-second scribble receives the same fulsome admiration as a 30-minute effort, how do they learn that persistence and hard work make a difference?

That's not to say that it isn't important to convey to our children (and others) that we love them because of who they are, not because of what they do. I'm not advocating conditional love. But when commenting on work done, specific and meaningful praise is what both feeds the heart and encourages more and better efforts.

The Stories of Emmy: A Girl Like Heidi by Doris Smith Naundorf (Xulon Press, 2010)

Doris Smith Naundorf is known in upstate New York as The Story Lady. The Stories of Emmy are taken from her one-woman play, Interweaving the Generations. Emmy, Doris's mother, grew up partly in her Swiss village of Muttenz, and partly in Paterson, New Jersey, where her family moved when she was ten years old. Her stories give a delightful glimpse into Swiss, American, and immigrant life in the early 1900's. (Grandchild warning: There is one sad incident requiring parental discretion; the stories are meant to be appropriate for chidren, but reality is sometimes harsh.)

Muttenz is near Basel (four minutes by train, a century later), and the stories are sprinkled with Baseldeutsch, the delightful Swiss-German dialect spoken there. A glossary is provided for each chapter.

Driving the several blocks to the train station, Emmy excitedly chattered to her father. "Will we get there in time, Vatti? she asked. "Mutti says we must be there early, so we will not miss the train."

"Jo, jo," replied her father. "In a country that makes such fine watches and clocks, of course the Zúúg runs on time. It is up to the passengers to be there early so the conductors can keep their schedule."

"The Zúúg, the train, is never late?"

"Of course not! We Swiss cannot even imagine such a thing!" her father assured Emmy.

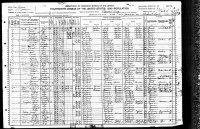

I couldn't resist finding Emmy, age 20, and her family in the 1920 census. (Click on the image to view a version large enough to read. Their name, Lüscher, appears without its umlaut.)