One of our grocery stores is inside a small mall with a play place. The rest rooms are not far away, but on a different floor, so a visit involves an elevator ride, and Vivienne was reluctant to go alone. No problem; Janet went with her and I stayed with the others. What makes this something worth reporting is what happened a little later.

Daniel was still happy in the play place, but Joseph and Vivienne decided they wanted to explore. They had a particular plan in mind, worked out the details with Mom, and off they went: up the elevator to the fifth floor, check out a particular store ("from the outside only, not going in"), come back down again and check in with Mom before going back into the play place. They did exactly that, returning in just a few minutes with big grins.

Only a few minutes later Vivienne left the play place again, and asked permission to take another exploratory trip. This was a slightly larger stretch for Mom and Grandma, since this time she would be on her own, without her older brother. But she did just great, and immediately announced that she had to use the bathroom again, and would do it all by herself.

She did just that. The look of triumph on her face was priceless. Well worth the maternal and grandmaternal nervousness we experienced upon watching the elevator doors close on our little adventurer.

I say this is growth and learning at its best.

- Her initial fears and dependence were accommodated without shaming.

- She stretched her comfort limits as part of her older brother's project.

- She repeated the same experience without her brother, making all the decisions (and pushing all the buttons) on her own.

- Finally, she repeated the bathroom trip completely independently.

This triumph was accomplished within a span of perhaps half an hour, with no pressure, no tears, at her own pace, when she was ready.

Joy all around.

This is for everyone, but especially our grandkids. It's a safe video if you watch it here and don't go directly to YouTube. Actually, there's nothing wrong with watching it on YouTube, except that then the comments are harder to avoid. Internet anonymity is an uncivilizing influence. (H/T Susan D.)

I think anyone should be able to get to the Posit Science BrainHQ Daily Spark exercises. At least, the e-mail states,

Every weekday, the Daily Spark opens one level of a BrainHQ exercise to all visitors. Play it once to get the feel of it — then again to do your best. Come back the next day for a new level in a different exercise!

If you try and can get to them without paying (even better if without registering), let me know. Or let me know if you can't. Since I have a subscription, I'm not sure what others see.

I find the BrainHQ exercises interesting and challenging, and I really have to get back to doing them on a regular basis.... (95 by 65 goal #70)

I've written before about Stephen Jepson and his Never Leave the Playground program. Now he has added brachiation to his collection of fitness "toys." Note his interesting form, without the usual swinging action of the body.

Note that Jepson's solution for an easier version while building up strength is very similar to ours, though his also works when the weather's too cold for swimming. I'll have to remember that!

Forty Ways to Look at Winston Churchill by Gretchen Rubin (Ballentine Books, 2003)

Forty Ways to Look at Winston Churchill by Gretchen Rubin (Ballentine Books, 2003)

What can Gretchen Rubin, famous for her books on happiness (The Happiness Project, Happier at Home), add to the multitude of books written about Churchill? Plenty, it turns out—at least if you are as ignorant of history as I am. Porter found it less interesting, because for him, there was little new.

My own interest in this book was piqued for a couple of reasons. While I was checking our library for Rubin's latest book, Better than Before, this—written well before her happiness books—popped up. Because we had recently watched the excellent Great Courses series on Churchill, I snapped it up.

My knowledge of Churchill being essentially no more than I had learned through those lectures, it was good, not tiresome, to hear the same stories again. Plus, the strength of Rubin's book is not in depth or special insight, but because she pulls together views of the man from many different biographical sources, demonstrating in the process just how difficult it is to write a biography—and impossible to write an unbiased one. In fact, the only real weakness I see in Rubin's book is that she can't hide her own great admiration for the man: she can't write the opposing side convincingly. But the facts are there, positive and negative, and I highly recommend Forty Ways as an easy-to-read introduction to this brilliant, complex man and his indomitable spirit.

Our grandson has a birthday coming up. Okay, two grandsons have a birthday coming up—the same day, in fact—but that's for the moment beside the point. The problem is that we were given a great gift idea, but I'm having an astonishingly hard time fulfilling it. He loves to read, and science books would be particularly welcomed. His current interest is planets but it's just as likely to become airplanes or frogs or the periodic table—just about any appropriate subject would be good. Reading/grade level is hard to determine. I'd have guessed maybe third, but I've seen plenty that Amazon has rated fifth through ninth that could be appropriate—I'm sure they're underestimating fifth graders, let alone ninth! But generally I'd say I'm looking for books aimed at elementary school age.

You'd think there'd be plenty, and there certainly is no dearth of apparently appropriate books. But oh, my. I don't want something obviously intended for schools, with questions and lesson plans. I don't want jokes, especially not dumb jokes, and most especially not jokes about flatulence. Flatulence? Really? In a discussion of Brownian motion? This was in an otherwise appealing book, and leads me to suspect the whole series; Amazon only lets you preview a few pages, and I'm left wondering what unpleasant surprises lurk, unexamined. Sad, because the series (Basher books) is otherwise one of the most attractive.

Condescension is almost as bad as flatulence. Isn't it possible to present facts simply without talking down to your audience? National Geographic books looked promising at first, but they don't have a lot of choice and are not free from condescension and stupid jokes. I'll probably get some nonetheless, but I'm hoping for suggestions from those of you with more experience. Bring them on, please!

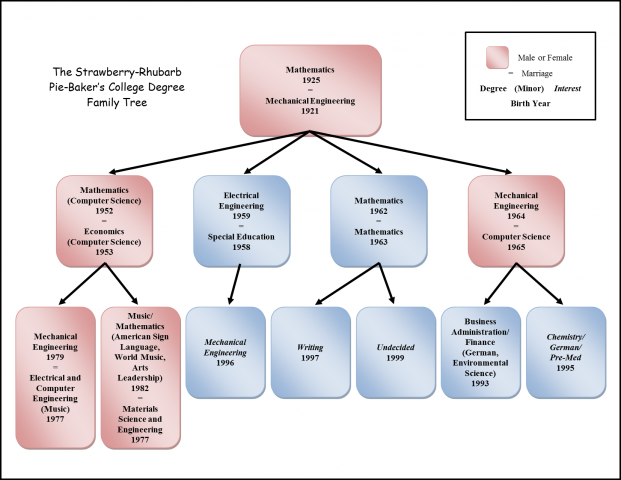

In the first comment to Saturday's Pi(e) post, Kathy Lewis asked about the math legacy of my mother (the one who introduced Kathy to strawberry-rhubarb pie). This inspired the genealogist in me to answer the question visually. (Click image to enlarge. Family members, please send me corrections as needed.)

Math-related fields clearly run in the family, by marriage as well as by blood. Some other facts of note:

- Most of the grandchildren (and all of the great-grandchildren, not shown in the chart) have not yet graduated from college. Their intended fields, where known, are shown in italics. One is very close to graduation, so I've left him unitalicised.

- In each generation from my parents through my children, there's been an even split between mathematics and engineering. However, with the next generation at nine and counting, I doubt that trend will continue.

- The other fields don't come out of nowhere: both of my parents had a vast range of interests.

- With one short-term exception in a time of need, every woman represented here clearly recognized motherhood as her primary and most important vocation, forsaking the money and prestige that come with outside employment to be able to attend full time to childrearing and making a good home. Every family must make its own choice between one good and another; this is not a judgement on other people's choices. Nonetheless, homemaking and motherhood as careers are seriously undervalued these days, so it's worth noting when such a cluster of women all choose to focus their considerable intelligence and education on the next generation. As daughter, wife, mother, aunt, and grandmother, I'm grateful for the choices these families (fathers as much as mothers) have made.

- Engineering is a long-time family heritage. My father's father (born 1896) was a mechanical engineer, and the first chairman of that department at Washington State University. His father (born 1854) was a civil engineer.

Permalink | Read 3263 times | Comments (6)

Category Education: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Genealogy: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Children & Family Issues: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Random Musings: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

How do you get kids to practice their instruments?

That's the question of all parents who can't help having occasional misgivings about the large outflow of cash going toward music lessons. As far as I can tell, the only honest answer is, "I don't know. It's different from child to child, anyway." Nonetheless, I have made a couple of observations while visiting Heather and family and will set them down for what they're worth.

- Every child here over the age of three takes formal piano lessons. The just-turned-four-year-old is eagerly awaiting informal lessons in the summer, and the start of the "real thing" in the fall. They all enjoy their lessons, partly because their teacher is one of the best-loved in the area, and partly because she's also known to them as Grammy.

- Everyone over the age of six walks or bikes to Grammy's house for his lesson. Not only is this convenient for their parents, but I believe it helps them "take ownership" of the lessons. It also means that if they forget their music books, they're the ones who have to turn around and go back, so responsibility is naturally encouraged.

- Even with these advantages, practice time was hit-or-miss, until a simple change was made. All the kids have morning and afternoon chores, which they are (mostly) in the habit of completing with minimal fuss, "Practice piano" was simply added to the list, and voilà, regular practicing.

- Best of all, the piano is located in the middle of everything. You can hardly go from one place to another without passing the piano. It gets played a lot, because it's there.

- Here's something I'd never have thought of: practicing is a whole lot more fun because the piano is not just a piano. It's a "real piano" rather than just a keyboard, but it is actually an electric keyboard built into a piece of furniture. Thus it comes with all the extras of a keyboard: the ability to record one's playing, multiple timbres, the ability to split the keyboard (have different instruments in the bass and the treble), and more. Yes, this leads to a lot of fooling around, but how many times do you think the kids would practice a particular piece or passage on a mere piano, compared with playing it with the piano sound, then the bagpipes, then organ, then flute, then with various sound effects? Multiple repetitions, painlessly.

I still don't know the secret to getting kids to practice. But I can recognize good tools for a parent's toolbox when I see them.

I'm still enjoying the Life of Fred math series, as you can see from my booklist; I hope to finish all that the Daleys have before I leave here. Despite what the author claims, it's not really a complete curriculum, but it's a fun supplement, it covers a lot of math, and there's really nothing like it. It covers a lot more than math, too, as five-year-old math professor Fred Gauss makes his way through his busy days. For obvious reasons, the following excerpt from Life of Fred: Jelly Beans caught my eye:

It is not how much you make that counts; it is how much you get to keep. Taxes make a big difference.

In the United States, the top federal income tax is currently 35%. The top state income tax is 11%. The top sales tax is 10%. TOTAL = 56% (56 percent means $56 out of every $100.)

In Denmark, the top income tax is 67%, and the VAT (which is like a sales tax) is 25%. TOTAL = 92%.

If you want to keep a lot of the money you earn, Switzerland's top income tax rate is 13%, and the top VAT is 8%. TOTAL = 23%.

Yes, it's an over-simplification (the book is meant for 4th graders), but it certainly helps distinguish Switzerland from Sweden.

Gifted Hands: The Ben Carson Story. This movie needs no more review than this: See it.

But of course I can't leave it at that. There are so many films, shows, books, and even Great Courses lectures I'd love for my grandchildren, especially the older ones, to experience, but there's always something that turns a great story into something NSFG. We used to be able to portray the rawer side of life in a way that left something to the imagination, but that sensitivity is now out of style. Gifted Hands, despite being non-rated, is a happy exception. There are some difficult situations and heartbreak, but nothing to detract from the story.

Ben Carson from inner-city Detroit, raised by a single mom (but what a mother!), failing in school, headed for trouble. Dr. Ben Carson, world-famous director of neurosurgery at Johns Hopkins. Gifted Hands tells the tale—fictionalized and condensed, but remarkably accurate for all that—of the transformation. The movie is enjoyable on many levels, from watching Ben's mother inspire her children to learn, to getting a glimpse of the Biltmore House library (professor's house in the movie), to realizing that it's possible to be both a top-notch neurosurgeon and a humble and good-natured person.

Great story. No caveats. Much inspiration. Enjoy!

The two best things about Geneva, Florida may be our friend Richard and the Greater Geneva Grande Award Marching Band, but thanks to Jon I've discovered a third: Stephen Jepson. Take time to watch this Growing Bolder video. It's less than eight minutes long and will show you why I'm enthusiastic about this 73-year-old man's ideas.

I'm looking forward to exploring his Never Leave the Playground website. After watching the Growing Bolder interview, my only negative reaction was that keeping so mentally and physically fit takes up so much of his time he can't possibly fit in anything else, and few people can (or would want to) live that way. But clearly that's not true—he's an artist, an inventor, and a motivational speaker—and his website promises you can begin with easy baby steps.

I wonder if we've passed him among the spectators at our Independence Day parades. Nah, he'd more likely be in the parade himself. But I'll keep my eye out this year for someone juggling on a skateboard.

I hope you all had a very merry Christmas. Ours began with a live cello carol concert and included the opportunity to serve Christmas dinner at the community kitchen where my nephew volunteers. Although the church was packed, there were actually more hands than work to do, so after a while Porter and I found ourselves part of the entertainment: singing Christmas carols for an appreciative audience. That was great fun, though pehaps a litte too much of a workout for my throat. Now we're enjoying the peace and rest of a Christmas evening at home.

But on to the business at hand.

I may have to amend this if I finish another book before the end of the year, but since I made my 52-book goal and have lots of other things going on this week, I'm going to go ahead and publish my 2014 reading list post now.

It's amazing that I can read at a pace of a book a week and still make so little progress on the shelves and shelves of unread books lining our walls. Some are gifts, some are books I bought because they looked promising, and most are from the many boxes of books I brought here when my father moved out of his large home into a small apartment. All of the books are ones I want to read, eventually. But a book a week is only 52 books read in a year, and what with all the new (to me) interesting books that come to my attention, plus books that are so good I want to reread them on a regular basis, the "unread" stack is growing rather than diminishing. Yet I keep on keeping on.

One particular feature of 2014 was the beginning of my determination to read all of the books written by Scottish author George MacDonald, in chronological order of their publication. This is an ongoing project, as there are nearly 50 books on that list. I didn't make this decision until April, which resulted in my reading a one of the books twice—once early in the year, and once when it came up in its chronological ranking. I have no problem with that.

I own beautiful hardcover copies of all these books, a wonderful gift from my father, collected over many years. I would prefer to be reading them book-in-hand, with my family all reading around me, enjoying a toasty fire in the fireplace or cool back-porch breezes. But in reality, this year I have read most of the MacDonald books on my Kindle (or the Kindle app on my phone), in spare minutes snatched here and there from a busy life, or in the few minutes between crawling into bed and falling asleep. George MacDonald's books are public domain and thus free on the Kindle, and are very good material with which to end the day on an uplifting note. This also liberates other time for reading books that I only have in physical form.

Here's the list from 2014, sorted alphabetically. A chronological listing, with rankings, warnings, and review links, is here. I enjoyed most of the books, and regret none. Titles in bold I found particularly worthwhile.

- 2BR02B by Kurt Vonnegut

- Adela Cathcart by George MacDonald

- Alec Forbes of Howglen by George MacDonald

- Annals of a Quiet Neighborhood by George MacDonald

- At the Back of the North Wind by George MacDonald (read twice)

- The Blue Ghost Mystery: A Rick Brant Science-Adventure Story #15 by John Blaine

- The Brainy Bunch by Kip and Mona Lisa Harding

- The Caves of Fear: A Rick Brant Science-Adventure Story #8 by John Blaine

- David Elginbrod by George MacDonald

- The Egyptian Cat Mystery: A Rick Brant Science-Adventure Story #16 by John Blaine

- The Flaming Mountain: A Rick Brant Science-Adventure Story #17 by John Blaine

- The Flying Stingaree: A Rick Brant Science-Adventure Story #18 by John Blaine

- The Golden Skull: A Rick Brant Science-Adventure Story #10 by John Blaine

- Guild Court by George MacDonald

- Handel's Messiah: Comfort for God's People by Calvin R. Stapert, audio book read by James Adams

- Half the Church by Carolyn Custis James

- The Hobbit by J.R.R. Tolkien

- The Jungle by Upton Sinclair

- Life of Fred: Australia by Stanley F. Schmidt

- Life of Fred: Cats by Stanley F. Schmidt

- Life of Fred: Dogs by Stanley F. Schmidt

- Life of Fred: Edgewood by Stanley F. Schmidt

- Life of Fred: Farming by Stanley F. Schmidt (all the Life of Fred books are worthwhile, but I particularly enjoyed Edgewood and Farming)

- The Life of Our Lord by Charles Dickens

- The Locust Effect by Gary A. Huagen and Victor Boutros

- Melancholy Elephants by Spider Robingson

- The Miracles of Our Lord by George MacDonald

- The Mysterious Affair at Styles by Agatha Christie

- Not Exactly Normal by Devin Brown

- The Peculiar by Stefan Bachmann

- Phantastes by George MacDonald

- The Pirates of Shan: A Rick Brant Science-Adventure Story #14 by John Blaine

- The Portent and Other Stories by George MacDonald

- The Princess and Curdie by George MacDonald

- The Princess and the Goblin by George MacDonald

- Ranald Bannerman's Boyhood by George MacDonald

- Robert Falconer by George MacDonald

- The Scarlet Lake Mystery: A Rick Brant Science-Adventure Story #13 by John Blaine

- The Seaboard Parish by George MacDonald

- The Secret Adversary by Agatha Christie

- The Shadow Lamp by Stephen R. Lawhead

- The Silent Swan by Lex Keating

- Smuggler's Reef: A Rick Brant Science-Adventure Story #7 by John Blaine

- Something Other than God by Jennifer Fulwiler

- Sometimes God Has a Kid's Face by Sister Mary Rose McGeady

- Station X: Decoding Nazi Secrets by Michael Smith

- Unbroken by Laura Hillenbrand

- Unspoken Sermons Volume I by George MacDonald

- The Vicar's Daughter by George MacDonald

- The Wailing Octopus: A Rick Brant Science-Adventure Story #11 by John Blaine

- Wool Omnibus by Hugh Howey (Wool 1 - Wool 5)

- Your Life Calling by Jane Pauley

Onward to next year!

Not to mention a great lesson about cotton, and a potential field trip for some New Hampshire homeschoolers we know! Check out the Occasional CEO's article this morning.

I'm not a big fan of going to the dentist, but yesterday's visit paid an unexpected benefit: the hygienist, a former neighbor of ours, shared this video with me.

Heather, this is especially for you, but I think Janet will appreciate it as well, despite her memories being less happy than yours. I enjoyed it a lot despite my own mixed feelings. There are plenty of good memories for Porter as well. :)

This video is just the trailer for a documentary project promoting music education, Marching Beyond Halftime. As such, it has relevance to many outside of our immediate family. Enjoy!

I haven't written much on the Common Core school standards mess (just this), but since Florida give us the opportunity to take sample tests, I couldn't resist checking out what was expected of third graders in mathematics. I was a math major in college and usually enjoy taking standardized tests, so it should have been a piece of cookie, as we say in our family in honor of one of Heather's college math instructors, who was, Ziva-like, idiom-challenged in English.

I'm strongly in favor of holding students, teachers, and schools accountable for what is learned in school. What's more, I have always had little sympathy for those who whine about the standardized testing that comes with a welcome concern for such accountability. For endless years schools have failed to work with parents, to open their doors and records to parents, and to provide parents any reasonable assurance that the massive amount of their children's time spent at school is not being wasted. They brought it all on themselves with their high-handed, "we know best, you just have to trust us" attitude.

And to those who complain that too much time is being wasted in school with teaching to and practicing for the tests, I always say the fault is not in the test, but in teaching to it and practicing for it. Any generalized testing system worth its salt should be able to count on the fact that test results are a representative sample of a student's knowledge; teaching to the sample undermines its reliability.

All that said, this is a test that requires practice, and specific, test-related teaching. First, doing math by mouse clicks instead of paper and pencil is a non-trivial exercise. In this I was aided by my hours of Khan Academy math work. But certainly students need time and practice to learn the specific testing interface.

Second, and most important, even with a bachelor's degree in math I found questions that made me stare blankly at the screen. I don't just mean i didn't know the answer: I hadn't a clue how to begin answering the question. (More)