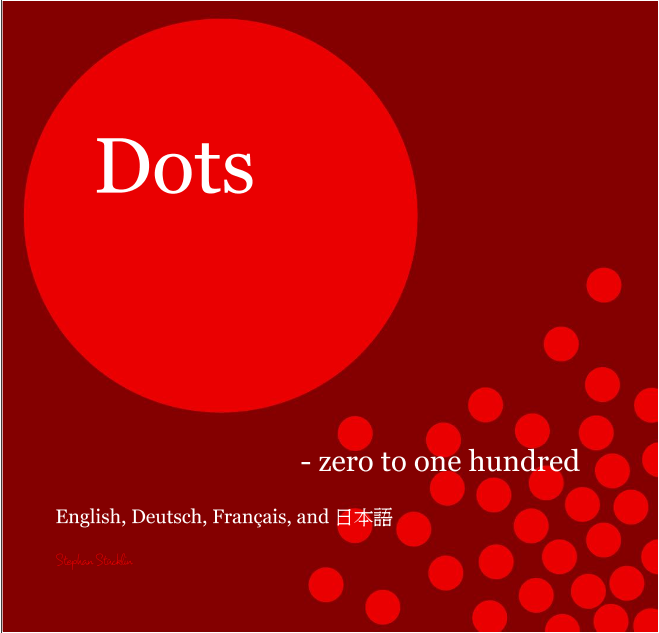

Woo-hoo! My copy of Dots: Zero to One Hundred arrived today!

I can't be griping all the time. Here's some great news for homeschoolers—and others who don't fit in the standard school model—who have suffered, as we did, from age discrimination by community colleges. Here are some excerpts from the encouraging story in tomorrow's Orlando Sentinel. (I know. Don't ask me why a column dated February 19 is available on the 18th, but it is.)

Two years ago, [Lake-Sumter Community College] refused to admit as a dual-enrollment student a then-12-year-old Center Hill girl who was more than academically qualified to study at the two-year community college. Instead of enthusiastically embracing Anastasia Megan, a brilliant young woman home-schooled by her parents, college administrators took the most backward stance imaginable and fought to keep her out.

The U.S. Department of Education's Office for Civil Rights in Atlanta, to whom Annie's family complained, recently closed the matter after LSCC eliminated its age requirement, trained employees to stop discriminating and offered Annie a chance to apply.

However, by the time LSCC offered to consider Annie in July 2011, it was clear that her course of study already had outstripped what the community college could provide. Starting in August, Annie, now 14, and another of the triplets, her brother Zigmund, will attend Queens University in Ontario, Canada. She was among 300 successful applicants to the college of business and commerce from a field of 5,000. ... Annie's brother is entering the university's engineering school (Annie's second choice), and the third triplet, Elizabeth, is enrolled in a high-school International Baccalaureate program.

[S]uch a ruling by the Office for Civil Rights is likely to have an effect on community colleges statewide. It's all about access in community colleges, and that's the way it ought to be. The Megan family neither asked for nor received a nickel in damages. The Megans didn't hire a lawyer. LSCC, however, spent about $12,000 on attorney fees fighting to discriminate against a kid whose achievements were remarkable. Asked why the college ever would fight to keep any student out, [College President Charles Mojock] said: "That was then, and this is now. We live and learn too."

Here's an interesting article from Newsweekon the popularity of homeschooling with "urban, educated" parents.

We think of homeschoolers as evangelicals or off-the-gridders who spend a lot of time at kitchen tables in the countryside. And it’s true that most homeschooling parents do so for moral or religious reasons. But education observers believe that is changing. You only have to go to a downtown Starbucks or art museum in the middle of a weekday to see that a once-unconventional choice “has become newly fashionable,” says Mitchell Stevens, a Stanford professor who wrote Kingdom of Children, a history of homeschooling. There are an estimated 300,000 homeschooled children in America’s cities, many of them children of secular, highly educated professionals who always figured they’d send their kids to school—until they came to think, Hey, maybe we could do better.

We've come a long way in the 25+ years of my experience. (Not that "evangelicals or off-the-gridders who spend a lot of time at kitchen tables in the countryside" comes close to being an accurate description of the home education movement at any time that I remember. It was always much broader than that.)

One consequence of the increasing popularity of homeschooling is that there is now enough collective knowledge that journalists are less likely to write utter nonsense. I found the article to be fairly accurate. An exception would be the section equating homeschooling with attachment parenting, which they define as, "an increasingly popular approach that involves round-the-clock physical contact with children and immediate responses to all their cues." This bizarre description makes it sound as if mothers continue to carry their eight-year-olds around in slings all the time. No normal one-year-old would put up with that, let alone someone of school age.

Other than that, it's a pretty fair article, considering it was written by someone on the outside looking in. And considering the really clueless articles that have been written on homeschooling over the years.

It's hard being a long-distance grandmother, whether the distance is 1000 miles or 4800. Certainly I'd rather our grandchildren live just down the street! But one compensation for the loss of frequent interaction is the joy of seeing how much the children change between visits. As we await the time when I'll have baby news to announce, I'll share a few stories of life with Joseph, 18 months old and soon to assume the important role of big brother.

John Ciardi said that a child should be allowed to learn, "at the rate determined by her own happy hunger." Joseph's current "happy hunger" is for letters and numbers. He has a wooden puzzle of the upper case alphabet that is the first toy he takes out in the morning, and again after his nap. This was supplemented at Christmas by the nicest number puzzle I've seen, which includes the numbers from 0 through 20 and arithmetic operators as well.

Permalink | Read 4212 times | Comments (13)

Category Education: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Travels: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Children & Family Issues: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Everyday Life: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

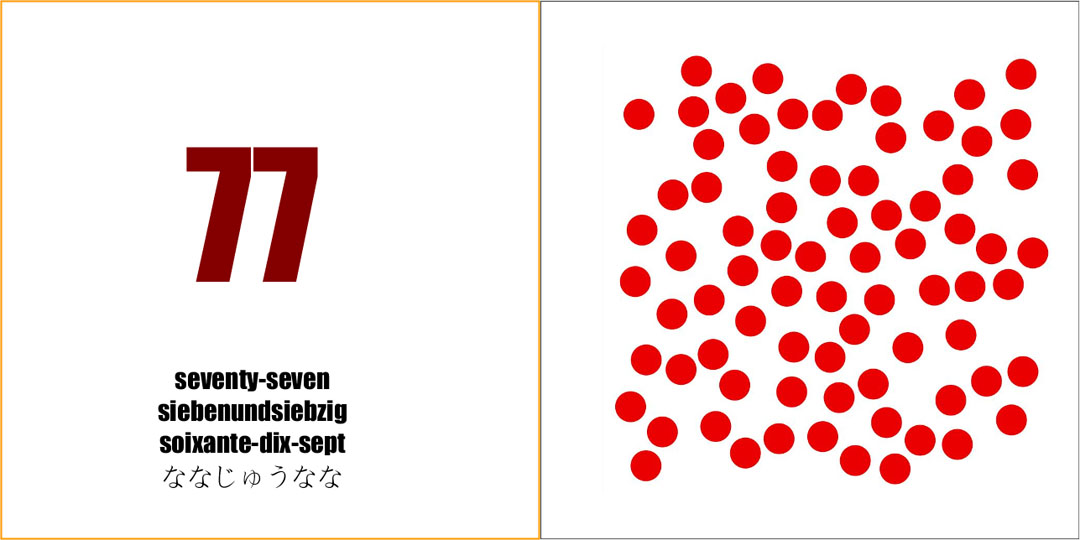

Our son-in-law, Stephan, has an artist's eye, and it shows in this book he created for our grandson, Joseph. He has published it, in three versions, through Blurb, so anyone may order a copy.

The inspiration was the absolute delight Joseph has shown, from a very young age, in the "math dot cards" from Glenn Doman's How to Teach Your Baby Math program, and his joy in reading books that show an object along with its name. As you can see, on the left side of the page is the numerical form of a number, with the written form in four languages (English, German, French, and Japanese), while the right side shows the number respresented by red dots.

Now Joseph will be able to examine his beloved dots whenever he likes.

Because there's no getting around the fact that specialty books are expensive, Stephan has produced three versions:

- The premier, full-length edition ($69.95) is hardcover and includes all numbers from zero to one hundred.

- The mid-length edition is less expensive ($47.95), hardcover, and includes all numbers from zero to fifty, plus the tens from sixty to one hundred.

- The bargain edition ($24.95) is softcover and includes all numbers from zero to twenty, plus the tens from thirty to one hundred.

This video was from six months ago, when Joseph was ten months old, but you can see his enthusiasm.

Stephan's Dots in Books page will keep us updated on how Joseph reacts to the book. You can also leave comments and suggestions there. Maybe there'll even be a new video some day.

For the past week I have been reliving elementary school.

My inspiration was this TED lecture from Salmon Khan of Khan Academy.

As a concept, Khan's idea is at once important, brilliant and frightening.

Important—because he is part of a growing movement to put education within reach of everyone. Well, everyone with access to an Internet connection, anyway.

Brilliant—because he turns school upside down. The teacher does not introduce the material; that's done via an online lecture, assigned for homework. Class time, then, becomes available for what is traditionally thought of as homework—working problems, writing essays—and discussion. Thus anyone who is confused or needs help has immediately at hand both the teacher and his fellow students. The teacher's time is allocated more efficiently, being spent on those who need help rather than those who don't. The time of the struggling student is also used more efficiently, because he can get problems cleared up on Exercise 1 rather than struggling uselessly through 2 - 20 or just giving up. Potentially, this system also helps other students, who find the work easy, to advance quickly to work that challenges them. Although experience has taught me that the last is not high amongst most schools' priorities, this system might make them more amenable to the idea.

Brilliant, also, is his insistence that everyone should be expected to master the material. I never did understand why any grade less than A is considered passing. In almost no subject in which I received an A did I feel I had mastered the material—how much worse is it for someone who earns a C? Perhaps in some subjects it doesn't matter much, but if you "pass" a child with a C in reading, or in math, you handicap him for life.

Frightening—because the system Khan has developed, at least when applied to the classroom, strips the student of privacy in yet one more area of his already over-exposed life. The teacher knows what videos he watches, what online exercises he has worked on, how he is spending his time, and where he is apparently struggling. All with good intent, of course, but the potential for abuse is there.

But back to my elementary school revisit.

Khan Academy has videos available on subjects wide and varied, but practice exercises are currently limited to mathematics. So just for fun I decided to try them out. (Yeah, I know. I have a weird idea of fun.) Here's what I discovered. Remember, I have done the exercises but not watched the videos, so this is not a fair review of the whole process.

- The exercises are pretty good, but do not exhibit much variety, and favor people with good test-taking skills. The program is cluttered with annoying "rewards" of the sticker-and-gold star type, which shouldn't be attractive to anyone over eight and which can have a negative long-term impact on learning. Nonetheless, I found the exercises very helpful for reviewing old concepts and drilling in my areas of weakness. Which brings me to

- Now I remember why I hated math until eighth grade, when I finally discovered algebra. Elementary school math is replete with the kind of exercises I loathe, such as multiplying and dividing large numbers with lots of decimal places, in which my propensity for understanding the concept but making careless errors is my undoing. Addition mistakes, transposed numbers, and sloppy handwriting are disastrous when you must get 10 correct answers in a row before moving on to the next lesson. I can't tell you how many times I completed nine problems correctly only to be reset to zero through a careless error on the tenth. However, I have more tenacity and patience than I did 50 years ago, or even at college, when I would trudge through the snow on a midwinter's night to have access to the Wang calculators available in the physics department, rather than do my lab calculations by hand. I made it through, not only the exercises that were supposed to show I could do such calculations, but the ones that anyone in his right mind would have used a calculator for, such as, An alien spaceship travels at 490,000,000 inches per second. How many miles does it travel in one hour? I did it, and my brain is better for it—but I have new sympathy for my grandson, who is currently finding math tedious.

Arithmetic : mathematics :: practicing scales : playing a Bach concerto.

I plow on. The exercises continue through the very beginnings of calculus. I find doing a few math exercises (even arithmetic exercises) to be a mind-refreshing break when other work gets frustrating. (See weirdness, above.)

And I love the idea of a mild-mannered nerd who leverages tutoring his cousins into changing the world.

If you can read this, thank a teacher.

I've seen it on bumper stickers for years, and just today at the bottom of my Penzey's Spices receipt. Only now did I finally wake up to the outrageous insult implied by that platitude.

With all due respect to teachers, of which there are some who are great and many, many more who do their jobs very well, how is it that we presume that a child, who requires only a reasonably supportive environment to learn to eat, to crawl, to walk, to understand, to talk, to love, to manipulate his environment—in short to acquire the essential skills of a lifetime in just a few years—how is it that we presume he cannot learn to read—a minor skill compared with all he has already learned—unless someone teaches him?

That's crazy talk.

I'm grateful for all who are willing to share their knowledge with others, and especially for those who make the sharing enjoyable. I suspect that those who do best, however, are the ones who realize they are not teaching so much as facilitating a child's natural learning.

But that turns out to be much too big an issue to write about just because I was annoyed by a bumper sticker, when I'm surrounded by vacation detritus, my husband is hungry, and I haven't yet managed that shower I promised myself after walking four miles in the 95 degree heat....

Don't ask me how I came upon Sporcle, but beware—it's addictive! There are quick quizzes for a wide array of subjects, and I've found them useful for refreshing the ol' memory on things I should know, as well as learning new interesting facts and just plain trivia. Not to mention spelling, as it doesn't matter if you do know the capital of Iceland if you can't spell Reykjavík, which I can't—yet. But I'm learning. Here are some of my favorites:

Countries of Europe Also North America, South America, Africa (up-to-date with South Sudan!) Asia, Oceania, and—if you have more time than I do—the world) and other geography games.

Books of the Old Testament (oh, those minor prophets!) Also New Testament, Apostles, Seven Deadly Sins, Roman and Greek gods.

U.S. Presidents: easy version (in order), hard version (random, by term of office).

Elements of the Periodic Table (accepts either "aluminum" or "aluminium").

Here's one for parents: can you name all the words in The Cat in the Hat?

Interesting trivia: common U.S. street names.

There's lots more, some more interesting and useful than others. I find the music category almost useless, although there are a few good ones if you dig, like Symphony Orchestra Instruments. Composers by Country was kind of fun.

Enjoy! And please post a comment here if you find good quizzes I haven't mentioned.

Eats, Shoots & Leaves: The Zero Tolerance Approach to Punctuation, by Lynne Truss (Gotham Books, New York, 2003)

Eats, Shoots & Leaves: The Zero Tolerance Approach to Punctuation, by Lynne Truss (Gotham Books, New York, 2003)

A panda walks into a café. He orders a sandwich, eats it, then draws a gun and fires two shots in the air.

“Why?” asks the confused waiter, as the panda makes towards the exit. The panda produces a badly punctuated wildlife manual and tosses it over his shoulder.

I’m a panda,” he says, at the door. “Look it up.”

The waiter turns to the relevant entry and, sure enough, finds an explanation.

“Panda. Large black-and-white bear-like mammal, native to China. Eats, shoots and leaves.”

Many thanks to DSTB for giving me this book, and thereby redeeming a past mistake on my part, made in response to a mistake on the part of our library.

I’d heard that Eats, Shoots & Leaves was a good book—though I knew little about it, as you will see—and so one day when I found it on tape at our library, I checked it out. I obviously was not paying attention when I put the cassette in our player, because apparently the wrong tape had been returned to the Eats, Shoots & Leaves packaging. What I heard was so uninteresting to me that I didn’t even finish the book, and don’t remember it now; it certainly wasn’t about punctuation.

“What?” you ask. “There’s something more boring than punctuation?”

Read Eats, Shoots & Leaves. You’ll never call punctuation boring again. You’ll laugh, and you’ll also learn.

One thing I learned is something I’ve suspected for a while now: the rules change when you cross the Atlantic. It’s not just the spelling (and pronunciation) of that metal out of which we make soda cans and “tin” foil. Truss encourages us to be sticklers for proper punctuation (hear, hear!)—a difficult enough task when bad examples surround us—but also cautions that sometimes what looks incorrect may be merely a cultural difference.

Be that as it may, the only thing that annoyed me about this short and pleasant book—and only as much as fingernails on a blackboard—was this British author’s persistent use of the British way of combining punctuation and quotation marks.

Many words require hyphens to avoid ambiguity: words such as “co-respondent”, “re-formed”, “re-mark”.

I would have called that plain wrong, but it turns out that putting the punctuation inside the quotation marks (<ahem> where it belongs!) is an Americanism.

Many words require hyphens to avoid ambiguity: words such as “co-respondent,” “re-formed,” “re-mark.”

I see the logic of the British system, but it still grates.

I also learned that there’s a reason for another annoyance ; this one is found in my beloved collection of George MacDonald books : What ? Colons, semicolons, question marks, and exclamation points ! find themselves preceded as well as followed by spaces. Truss provided the answer to my puzzlement: these books are facsimile editions, and that now strange punctuation procedure was at one time the Way Things Are Done.

Are you confused by the Way Things Are (or Should Be) Done Now? Check out Eats, Shoots & Leaves for some seriously amusing enlightenment.

A headline recently provided by my Google News feed illustrates the importance of correct punctuation.

Ratko Mladic arrested, Hillary Clinton in Pakistan

Imagine it now, without the comma:

Ratko Mladic arrested Hillary Clinton in Pakistan

Punctuation matters. So read, mark, learn, and inwardly digest—and enjoy!

Outliers: The Story of Success, by Malcolm Gladwell (Little, Brown & Co., New York, 2008)

Outliers: The Story of Success, by Malcolm Gladwell (Little, Brown & Co., New York, 2008)

Malcolm Gladwell’s books always turn my mind upside down. He may not always be right, but he’s always exciting.

What makes a superstar? What differentiates Bill Gates from the average computer geek, the Beatles from a garage band, the top athletes from the wannabes? Talent, certainly, and hard work—but Outliers reveals that the most critical factors are often surprising, even random.

The 10,000 hour rule Talent, we generally believe, is something we are born with. Intelligence, musical ability, athletic skill: you either have it, or you don’t. There is more excuse than truth there, however. There is a threshold of talent required in any field, but beyond that, experience is the all-important key.

Practice isn’t the thing you do once you’re good. It’s the thing that makes you good.

Study after study has shown that it takes about 10,000 hours of practice to achieve world-class expertise in any field. That’s 2,000 hours per year—the equivalent of a full-time job—for five years. The opportunity to get those 10,000 hours, at the right place and time, makes superstars. For Bill Gates it was a series of unusual circumstances, beginning in middle school, that gave him access to computers that even most college students did not have. Before he dropped out of Harvard to make history, Gates had been programming for well over 10,000 hours.

Thanks to a chance encounter—and some illicit incentive—the Beatles found themselves in a set of gigs that required an extraordinarily long performance commitment: up to eight hours per night, seven days a week. It was the making of the group. By the time they came to America in 1964, they had some 1200 live performances under their guitar straps.

Or, as Shinichi Suzuki said, “Skill equals knowledge plus 10,000 times.” Another gem from the Suzuki world (though I’ve seen it attributed in several ways, most commonly to Vince Lombardi): Practice doesn’t make perfect. Only perfect practice makes perfect. Clearly one must put more into those 10,000 hours than just time. (More)

The Mother Tongue: English and How It Got that Way (first published 1991, reissued by Perennial 2001) and Troublesome Words (first published 1984, revised 1997, reissued by Penguin Books 2009), both by Bill Bryson

My father and my sister-in-law became hooked on Bill Bryson as a writer; perhaps it is now my turn.

For the first twelve chapters, The Mother Tongue is an accessible, page-turning look at the English language: where it came from, why it’s so popular, and how it came to be simultaneously one of the easiest and one of the hardest languages to learn. (More)

You may remember Michael Merzenich as one of the major researchers mentioned in The Brain that Changes Itself by Norman Doidge. Merzenich is no doubt a better researcher than a speaker; this lecture is not nearly as good—and certainly not as comprehensive—as the book. But it will take less than 25 minutes of your time, and is worthwhile if only for his explanation of the dangers of white noise—continuous, disorganized sound—to an infant's brain, and for the hope he holds out to those of us who grew up with the depressing idea that once you reach adulthood (or perhaps early teens, or even age six, depending on who you believe), you are basically stuck with the brain you've got.

Michael Merzenich on re-wiring the brain

(Granchild warning: I don't know if you consider "crap" objectionable, but there are a few instances between 17:00 and 18:30.)

Unlike many people, I never dreamed of visiting foreign countries. I like being home. If I have family around me and good work to do, why should I go elsewhere?

Well, God clearly intended to broaden me a bit. Between having family now living overseas and the opportunities provided by Porter’s job, I’ve done a whole lot more travelling than I’d ever intended.

That’s a good thing—and not just because some of that travel has led me to valuable genealogical research opportunities. Most recently I was struck by how personal it makes world events.

The tragedy in Japan has more impact on me because we were there. Janet and Stephan each lived and worked in Japan for a year; we met Janet’s friends, went to her church, walked the streets of her town. That may be why this video struck me harder than the more spectacular footage. This is not where Janet lived, but it feels familiar, particularly the voice calling over the loudspeakers. That makes the impact hit home.

I used to wonder why churches sent youth groups on week-long missions trips. Sure, the kids do some good: painting, some minor construction work, brightening some children’s lives for a few days. It’s not that they don’t do work that needs to be done—but wouldn’t it be more cost-effective, and better for the community, to take the money spent sending American kids to places in need and instead hire local people to do the work?

I still think that would be a better use of the money, short-term. But who can analyze the future value of creating a personal connection between young people and another place, another culture, another way of life?

Study can help build that connection; I still feel tied to Ethiopia because of a mammoth project I did in elementary school on that country. But study and travel—if we can make it happen for our children, they and the world will be better for it. I know of nothing more likely to erase false images (both negative and positive) than actual interaction with real people in real places.

How to Be a High School Superstar: A Revolutionary Plan to Get into College by Standing Out (Without Burning Out), by Cal Newport (Broadway Books, New York, 2010)

If I could recommend two books to help a 12-15 year old student prepare for college, it would be Alex and Brett Harris's Do Hard Things and this one. Some of the political and religious views expressed in the former set my teeth on edge, but it's well worth the effort to get past that reaction, because Brett and Alex write well, and what they are saying is incredibly important, not just for teens who share their beliefs, but for everyone, of any age.

How to Be a High School Superstar is altogether different in focus, but I can boil the best of both books down to this: Life doesn’t begin when you graduate from high school. or college, or grad school. You can do hard things, good things, amazing things, now. Or, rather, in a little while from now, if you are willing to put forth some effort in the right direction. (More)

Don't you just love it when an otherwise obscure reference clicks in your mind?

First, one of my favorite non-family blogs, The Occasional CEO, has a post entitled Steampunk in Pictures. Steampunk, Wikipedia tells me, is a subgenre of science fiction. Wait—I cut my teeth on science fiction, and I'd never heard of it? Turns out steampunk came of age during the 1980's and 90's, when our kids were cutting their teeth and I was too busy to keep up with that part of my former life. (More)