I've backed a few Kickstarter projects in my time, at the intersection of an interesting concept, a person or cause I'd like to support, and an affordable price. That's how my beloved Green Ember books began, though they've since moved on to more standard publishing.

That's not a one-way street. Brandon Sanderson—my eldest grandson's favorite author, whose books are prized by several others in our family, including me—has a current Kickstarter project going, even though he's multi, multi-published in the ordinary way.

But I don't think I'll be backing this one.

First, the lowest tier of support is $40, which is not exorbitant considering you get four e-books at that level, and $10 is a pretty standard price for his books on Kindle. But I can easily wait for a sale. I'm a fan, but nowhere near a FAN fan.

More importantly, Sanderson hardly needs my support. Even after deciding not to back the project, I've been checking in occasionally on the Kickstarter page for the amusement of watching the numbers climb. When I was a young child, I loved to watch the numbers grow on the gas pump as the tank filled, and I always rooted for a new record high. My parents didn't quite share my enthusiasm.

Sanderson's project is now the number one Kickstarter project of all time, and that by a huge margin.

I thought a million dollars was an ambitious goal, but apparently it had reached ten million before the first day was over.

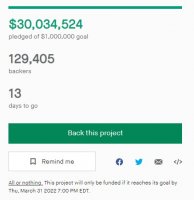

Eighteen days into the campaign, I captured the following screenshot:

It will be much higher by the time I hit, "Publish." The pace has slowed a bit, but you can still watch the numbers grow in real time, even if it's now more of a 1950's gas pump pace than 2022.

More than 17,000 people have backed this project at the highest ($500) level.

How's that for an author most of you have never heard of?

Permalink | Read 1153 times | Comments (1)

Category Just for Fun: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

Porter has been doing yeoman's work sorting through the information, misinformation, and distorted information available to us about the war in the Ukraine. I don't have the patience. But it is amusing, when it's not depressing, to listen to him watching the nightly news: "They're reporting as new something I heard about yesterday," and "that video is at least three days old."

In the process, he discovered Chris Cappy. He's an Iraq vet with an informative and entertaining style that goes so far as to make military history, weapons, strategy, and tactics interesting even to me. His updates on the war are—as far as in my ignorance I can tell—knowledgeable and fair, with a minimum of emotion and propaganda.

The following video (24 minutes) is a good example, which not only gives an update on the war (as of March 15), but makes a good case for why Big Tech's shutdown of Russian sources on social media is dangerous as well as insulting.

Remember 2019? Must have been at least a decade ago, right? Who'd have thought we could pack so much pandemic, riot, and war into two years.

Nonetheless, my post for March 16, 2019 is at least as appropriate now as it was then, so I'm repeating it.

Sandwiched between 3:14 (Pi Day) and 3:17 (St. Patrick's Day) is

3:16 (Greatest Love Day)

John 3:16, that is.

For God so loved the world, that he gave his only begotten Son, that whosoever believeth in him should not perish, but have everlasting life.

In honor of which I present this beautiful anthem, John Stainer's God So Loved the World. No, that's not our choir. But Porter and I have sung this many times and it's one of our favorites.

Permalink | Read 1133 times | Comments (0)

Category Hurricanes and Such: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Inspiration: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

Are you a person who prays?

Are you praying for the Ukraine, its people, and its leaders? Good. They need it, obviously and desperately.

But are you also praying for Russia? Are you praying for Vladimir Putin and his advisors?

I can't speak for any other traditions of prayer, but for Christians our responsibility is crystal clear: In addition to other Biblical precedent, we have a direct command from Our Lord to love and pray for our enemies.

If that isn't good enough, consider that the Russian people didn't ask for this. If we rightly fear domination of the people of Ukraine by Putin and the Russian oligarchs, we know that the Russians have been living that life all along.

Our sanctions may convince Putin to withdraw his forces, or they may drive him into desperate actions and alliances that will come back to bite us hard. That's not clear yet. What is definite is that they have tanked the Russian economy, and the Russian people are heading into financial hardship of a kind that has passed out of the living memory of our own country.

If their suffering is not enough to convince you to pray for them, consider what happened in Germany after World War I, when the winners of that conflict made certain that the German economy would be completely devastated.

Have I convinced you to pray for the Russians? Now, how about President Putin? It is so easy to fear him, and to hate him!

For Christians, again the command is clear: we must love him, and pray for him. (We don't have to like him.) Regardless of how we feel about him, he is as valuable in the eyes of God as we are. And if, as we'd like to believe, he were less worthy of our prayers, that would only mean he needs them more.

But if that's not enough, we must pray for Putin for our own safety's sake. (Did you catch the nod to A Man for All Seasons?) He's a man in command of a large and powerful nation, with his finger on the nuclear button. We all know from experience how much damage the last two years of pandemic isolation have done to people's mental health. From all accounts, Putin has taken this isolation to an extreme. If he was unstable before, what of now?

What's more, in our collective response to his invasion of the Ukraine, we have been backing him into a corner with no way to save face. We seem determined to defeat him utterly and humiliate him, forgetting that cornered bears are exceedingly dangerous. Finding a win-win situation is not capitulation; it's wise diplomacy, and much more likely to lead to a lasting peace.

I don't know how this dangerous and tragic situation should properly be handled. I don't know if we are being Neville Chamberlains or if we are being driven by the fear of making his mistakes into making more disastrous mistakes of our own. I don't see a Winston Churchill on the horizon.

I do know that the one thing we can do is to pray. For the Ukraine, and for Russia. For NATO, for the European Union, and for all the world leaders who don't know what they're doing and are doing it very enthusiastically.

A lot of other subjects have been taking up my mind space, and my blog space, for a long time, so I was delighted when a friend shared this bit of mathematical fun with me. (22 minutes)

Permalink | Read 1026 times | Comments (0)

Category Just for Fun: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

This interview with GiveSendGo co-founder, Jacob Wells was so uplifting I have to share it. I'd written about GiveSendGo briefly before, and what little I knew about it induced me to listen to the whole interview, despite it being nearly two hours long. The advantage of unedited interviews is that you get them uncensored; the disadvantage is that they are l-o-n-g. But this one does very well being played at 1.5x speed, as long as you're willing to overlook the fact that it makes everyone sound overly and artificially excited. While there are a couple of places where it is better to be watching, for the most part just listening is fine, so you can exercise, wash the dishes, or drive and enjoy it without feeling guilty.

Those who followed the Freedom Convoy story in Canada will appreciate information about the legal consequences for GiveSendGo of the Canadian government's threat to seize assets without benefit of court order, as well as the malicious hack they suffered and how they have responded. Others might find this tedious, but anyone can enjoy hearing about Wells' early life (he grew up in New Hampshire and has 11 siblings), his adventures testifying in front of a Canadian parlimentary committee, and the reasons why GiveSendGo does not discriminate against people or organizations (including the Church of Satan) as long as the projects involved do not violate a few minimal conditions (such as legality).

Rarely have I seen such a positive integration of a person's business, life, and faith. As I said: uplifting. I hope those of you who have time to listen enjoy it as much as I did.

Permalink | Read 1453 times | Comments (0)

Category Hurricanes and Such: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Inspiration: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Freedom Convoy: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

As a child, I listened to 'way too many repetitions of Tom Lehrer's That Was the Year that Was album; consequently I've lately been afflicted by the following earworm: "So Long, Mom (A Song for WWIII)."

I almost didn't post it—not for reasons of sparing you the earworm, but because the war in the Ukraine is so heartbreaking. And frightening. We pray repeatedly and fervently for the Ukrainian people and their leaders, and for the Russian people and their leaders (because as Christians we don't have the option of praying only for our favorite teams). Not to mention prayers that this not lead to World War III.

But humor has a place in serious situations, and it was a serious situation—the height of the Cold War—when Lehrer wrote the song.

So long, Mom,

I'm off to drop the bomb,

So don't wait up for me.

But while you swelter

Down there in your shelter,

You can see me

On your TV.

While we're attacking frontally,

Watch Brinkally and Huntally,

Describing contrapuntally

The cities we have lost.

No need for you to miss a minute

Of the agonizing holocaust.

Who, in the 1960's, could have imagined the continuous real time coverage, the drone footage, the uploaded personal cell phone videos, and the satellite photos that make this war so "up close and personal"? Lehrer, now 93 years old, is almost certainly watching it himself. On a color television set.

Permalink | Read 1165 times | Comments (1)

Category Hurricanes and Such: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

It's "Museums on Us" weekend, and time to take a look at what might be new around town. Usually that means the Orlando Museum of Art and the Mennello Museum of American Art. Sometimes they have lovely exhibits, and we might go back to take another look at some of what we saw last October.

But the museum websites and the descriptions of new exhibits are not inspiring this month. Here, from the Mennello's site, are a couple of paragraphs that could not possibly have been designed to draw us in.

Many of the artists presented here approach their creative practices conceptually and methodologically, as a means of researching, solving, expressing, and effectively visualizing increasingly complex theories and stylistic ideas across time and disciplines. They have drawn upon personal experience, art history, advances in science, and popular culture to create works that unify formal art theory with current understandings in fields including anthropology, biology, math, philosophy, physics, and psychology. Broadly, the themes explored by the artists fall into reobserving and reimagining of traditional subject matter and the emotional content imbued in still lifes, landscape, and the figure.

“The work ... presented in this exhibition challenges perceptions of language, identity, preservation, and adaptation in both real and hypothetical worlds,” said Katherine Page, curator of art and education, Mennello Museum. “I am especially interested in artistic production, as its contextualizing framework runs parallel to the scientific method that combines the decades-long history of science, printmaking, and modern and postmodern art developments. The artists here are researchers, observers, experimenters, and publishers. As publishers, they share their exciting results—renderings of creation, communication, and conceptualization with a public beyond traditional, specialized academic fields.”

Huh?

I'm not picking on the Mennello in particular. This kind of verbiage abounds in art museums all over. I'm accustomed to dealing with technical language in other fields, and I grant that maybe this makes sense in the higher echelons of the art world, but to the hoi polloi like me it's more than incomprehensible: it sounds utterly irrational. Why would I want to spend time with art that "challenges perceptions of language, identity, preservation, and adaptation in both real and hypothetical worlds"? When I go to an art museum, I'm seeking the good, the true, and the beautiful. Ordinary life is enough of a challenge for me.

When I am working on a problem, I never think about beauty but when I have finished, if the solution is not beautiful, I know it is wrong. — Buckminster Fuller

Permalink | Read 1389 times | Comments (0)

Category Random Musings: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

When we were in Chicago recently, our first meal was at the amazing Russian Tea Time restaurant. It was a special occasion; if we lived in Chicago, the expense would make our visits rare. But if I were there now, I'd make a point of taking in another of their wonderful Afternoon Teas. Whatever we may think of the recent actions of Vladimir Putin, it makes no sense to penalize our Russian neighbors. This is the letter we received from the owners of Russian Tea Time.

Dear RTT patrons and friends,

We are heartbroken by the recent news; our thoughts and prayers are with those who are affected by this inhumane and despicable invasion. We do not support politics of the Russian government. We support human rights, freedom of speech, and fair democratic elections.

Украинцы (Ukrainians), the world is with you, the world is behind you. Stay strong, our hearts are with you!

The past two years have been so very hard on restaurants; they don't need any more grief.

Besides, you never know who it is you're actually affecting. The owners of our favorite place for sushi in Central Florida (now, alas, no longer in business) were Vietnamese, not Japanese.

The owners of Russian Tea Time are Ukrainian.

Permalink | Read 1522 times | Comments (2)

Category Hurricanes and Such: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Politics: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Travels: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Food: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

Milestone note: This is my 3000th blog post. That calls for something serious, but not depressing. Here you go:

Fairy tales ... are not responsible for producing in children fear, or any of the shapes of fear; fairy tales do not give the child the idea of the evil or the ugly; that is in the child already, because it is in the world already. Fairy tales do not give the child his first idea of bogey. What fairy tales give the child is his first clear idea of the possible defeat of bogey. The baby has known the dragon intimately ever since he had an imagination. What the fairy tale provides for him is a St. George to kill the dragon. — G. K. Chesterton, 1909 ("The Red Angel")

Since it is so likely that [children] will meet cruel enemies, let them at least have heard of brave knights and heroic courage. ... Let there be wicked kings and beheadings, battles and dungeons, giants and dragons, and let the villains be soundly killed at the end of the book. — C. S. Lewis, 1952 ("On Three Ways of Writing for Children")

I write stories for courageous kids who know that dragons are real, that they are evil, and that they must be defeated. I don’t do that because I want to hurt children, but because children do and will face hurts every day. I don’t want to expose them to evil, I want to help them become people for whom evil is an enemy to be exposed. I want to tell them dangerous stories so that they themselves will become dangerous—dangerous to the darkness. — S. D. Smith, 2022 ("My Blood for Yours")

Smith's essay in video form (three minutes).

P.S. There's a new Green Ember book to be released soon, Prince Lander and the Dragon War. Time to reread the previous books in preparation!

I woke up this morning at 4:00, troubled by the news Porter had delivered when he came to bed about midnight last night. Life has been emotionally exhausting on so many fronts in the last two years that it can be a struggle to remind myself that we are among the most blessed and least troubled people in the world. Pain works that way.

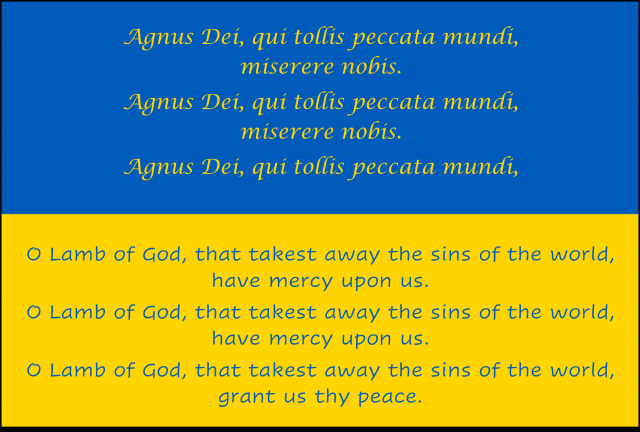

Arising, I went in search of news, and was greeted by this instead. It was livestreamed at midnight, and is from the church we visited when we were in Chicago. (Mea culpa—I know I have yet to write about that wonderful trip.)

It is not likely to be a prayer tradition of many of my readers. But it was infinitely better for my mental and spiritual health than a news report—full of fear and adrenaline and necessarily of limited accuracy—would have been.

I know many of you think I have better things to do than follow the protests in Ottawa, and you're right. You can blame my 10th grade World Cultures teacher. You can also blame him that I graduated from high school with near-zero knowledge of world history. But he was one of my favorite teachers.

Instead of giving us a broad general knowledge of the world, Mr. Balk chose to lead us deeper into a few limited areas of particular importance in the late 1960's: Southeast Asia, the Middle East, and the American civil rights movement. He also encouraged us to follow the unfolding of current events, in particular the Prague Spring. That's a lesson I never forgot.

Plus I love David-and-Goliath freedom stories.

Will this really come to be seen by future eyes as an important historical event? Time alone will tell what impact the Ottawa protests will have on the restoration of the rights of Canadian citizens. But watching the cross-cultural camaraderie of this diversity of Canadians who, despite the seriousness of their grievances, maintained for three weeks the peace and joy of their protest, has done my battered and cynical heart much good. If we had not put in the time to watch hours and hours of live, boots-on-the-ground coverage, and relied simply on general news stories, we would never have known the truth.

I have loved Canada since I was a child. Where I lived in upstate New York, crossing the border was not exceptional, and stores both accepted and gave out Canadian change. (The two currencies were closer to par back then.) At one point I could sing the Canadian national anthem in both English and French, along with most of the other songs on my record of Canadian folk music. Canada and Switzerland were the two places I had declared myself willing to live if I had to live somewhere other than the United States. Sadly, as time went on Canada's social and political policies, like those of my long-beloved home state of New York, convinced even this life-long Democrat that it would take a major change to make me willing to live there.

Whether or not they turn out to be historically significant, the past three weeks have restored my hope for our northern neighbors. True, the governmental responses, plus the realization that their Constitutional rights are not nearly as robust as ours, makes me even less inclined to move there. (That and the weather.) But if the strength, love, joy, and unity demonstrated by these protesters is infectious, I have hope. Despite the genuinely outrageous actions taken by Prime Minister Trudeau and other leaders, I'm actually more optimistic in general than I have been in over a year.

(But really, even those peaceful people sure could learn to clean up their language.)

Permalink | Read 1107 times | Comments (1)

Category Hurricanes and Such: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Freedom Convoy: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

It's nearly an hour long, but if you want to know the truth behind the origins, organizers, goals, and strategies of Freedom Convoy 2022, this Viva Frei interview with Ben Dichter is well worth your time, even if you don't watch it all. No rants, no anger, just a calm, informative interview with a well-spoken official representative of the Convoy.

If my memory serves me correctly, I have been to an emergency care facility twice in my life. Unlike my brother, who apparently volunteered at some point to take on the major injuries, up to and including appendicitis, for our family.

The first time was my freshman year in college, when in chem lab I splashed potassium dichromate in my eye. The second was last Saturday.

I keep my kitchen knives sharp. I mean really sharp. They don't get put away without a touch-up honing. This is mostly a great thing, but let me just say that I take issue with the conventional wisdom that you're more likely to cut yourself with a dull knife than a sharp one. Brief encounters with a blade, which would never have broken the skin in my pre-knife-sharpening-obsession days, easily draw blood. They quickly heal and never hurt more than a paper cut, but it's annoying to try to keep the blood out of the vegetables. I mean, there goes any hope of getting approval by the Vegan Authorities.

Back to the story.

As I said, any cuts I get are almost always very minor. Almost. But even great chefs make the occasional mistake. Blame my new glasses, blame my distractable brain that had just received some nasty news on the financial front—but on Saturday when I was cutting up vegetables for a stew, just for a moment I lost the ability to distinguish between a carrot and my thumb.

I knew immediately that it wasn't serious, but neither was it a wrap-it-in-a-paper-towel-and-forget-it affair. I had made a nice, circular slice that very nearly lifted the top off my thumb. It was not deep, but "deep enough." I'm familiar with skin flap wounds, and know they don't tend to heal well on their own; mostly they dry up and fall off. I judged this to be a little too much for that to be desirable.

Wouldn't you know, Porter had moments before detailed to me his agenda for the afternoon. I wrapped up my thumb to staunch the blood, turned off the two stove burners where pans were cheerfully sizzling with the start of dinner, walked into his office and began, "I'm sorry to derail your afternoon plans, but...."

Let me just say this about my husband. He can get bizarrely upset about the littlest things, like a traffic light turning red, or a dice roll going against him in a board game. But give him a real emergency and he suddenly becomes calm, cool, and focussed.

Having had his own encounter with finger wounds, for which a doctor later admonished him, "You should have had stitches for this," he never questioned the need for emergency care. It didn't seem the right thing to go to our primary care doctor for, and there's no way I wanted to spend all day in a hospital emergency room after being subjected to a COVID test. Instead, he phoned our local doc-in-a-box CentraCare facility and (having been placed on hold) started driving. I have no idea where we were in the queue, because we were still on hold when we arrived and walked up to the receptionist.

Other than the phone call, I have to say that from beginning to end our treatment at CentraCare could not have been better. The waiting room was not crowded, and even so I jumped to the head of the line. Apparently blood, even when you've cleaned up and stopped the bleeding with a neatly-wrapped bandage before leaving home, gets people's attention.

The nurse (?) who attended me was great, and knew how to put me at ease. We had a great conversation because she's an EMT and studying to become a paramedic, and of course I had to talk about the EMT's and doctors in our family. Having determined that my wound did, indeed, need stitches, she then went off to inform the doctor.

Thus began the longest wait, which only makes sense because there was no longer an emergency. And I have no complaints, because when the doctor finally arrived, he gave me the (no doubt erroneous) impression that he had all the time in the world to attend to my needs. That's a precious gift, and rare from a doctor.

Turns out I didn't get stitches after all. After soaking my thumb in a "surgeon's soap" solution while he went to check on someone else, he told me that the cut was so neat that trying to stitch it would do more harm than good. (Did I mention that my knife was really sharp?) Instead, he just glued the flap in place with some specialized medical skin glue, and gave me a splint to wear.

That little device is brilliant. For one thing, it makes the wound look so much more impressive, and more worthy of having received medical attention. But mostly, it is great at keeping me from re-injuring the thumb. Without it there to protect against bumps and other stresses on the healing skin, and to remind me pay attendion, I would probably have re-opened the wound dozens of times in the course of daily life. The biggest frustration is not being able to get the thumb wet for seven days, which means I have to miss our water aerobics classes. And have you ever tried to wash just one hand? I have a friend whose neice was born with but one arm, and apparently has always managed beautifully. (When she was a small child, her younger sister was heard to exclaim, "I wish I only had one arm, so I could tie my shoes, too!") Let's just say I'm more impressed than ever. I also have a gut-level appreciation for what we were taught in high school biology class: the value of our opposable thumbs.

On Wednesday I went back to CentraCare to be told that everything is going great. (But I still can't get it wet till Saturday.) I made a point of telling them how impressed I was with their service, from the receptionist to the doctor and everyone in between.

That doesn't change the fact that I'm willing to wait another 50 years for my next visit.

P.S. Our initial stay was short enough that the food left on the stove was still safe when we returned home. Porter took over the cutting of the vegetables, and the stew was great.

I fully intended to post something lighter today, but history has no pause button.

Anyone receiving a cancer diagnosis, or answering the phone to learn of a loved one's fatal auto accident, or having his home and belongings destroyed by fire, flood, or storm, knows how suddenly the world as he's always known it can be obliterated.

In the past two years, much of the world has experienced a lesser version of this lesson. Here in Florida, we have been greatly blessed by a less-heavy-than-most governmental hand on our pandemic response, but we've still suffered business closures, job loss, postponement of essential medical procedures, educational disruption, supply chain problems, and a whole host of mental health issues. It's been a disaster that took everyone by surprise, though other states and other countries have suffered much more.

In the blink of an eye, a simple executive order at any level of government can take away your job; close your school; shut your church doors; kill your business; deny you access to health care, public buildings, restaurants, and stores; forbid family gatherings; lock you in your home; stop you from singing; and force you and your children to submit to medical procedures against your will.

It astonishes me how many people are okay with this. At one point I was even one of them.

Canada has now taken this to a higher level.

It is clear from watching about 20 hours of livestream reports from Ottawa (there's a lot more if you have the endurance to watch), that the anti-vaccine-passport protest called Freedom Convoy 2022 is most notable for its peaceful unity-in-diversity—along with keeping the streets open for emergency vehicles, allowing normal traffic to move in areas away from the small immediate protest site, keeping the streets clean of trash and clear of snow, complying when the court ordered them to cease their loud horn blowing, and having a happy, block-party-like atmosphere.

Elsewhere, the unrelated-except-in-spirit protest at the Ambassador Bridge border crossing in Windsor, Ontario had already been ended peacefully by court order and the bridge reopened.

Why, at that point, did Prime Minister Justin Trudeau decide he needed to invoke, for the first time ever, Canada's Emergencies Act, designed to give the government heightened powers in the case of natural disasters or other situations of extraordinary and immediate danger? Here are some quotes from a BBC article about it.

[Trudeau] said the police would be given "more tools" to imprison or fine protesters and protect critical infrastructure.

Just what this means is not detailed, but the following is crystal clear. Bold emphasis is mine.

Deputy Prime Minister Chrystia Freeland said at Monday's news conference that banks would be able freeze personal accounts of anyone linked with the protests without any need for a court order.

Vehicle insurance of anyone involved with the demonstrations can also be suspended, she added.

Ms Freeland said they were broadening Canada's "Terrorist Financing" rules to cover cryptocurrencies and crowdfunding platforms, as part of the effort.

You can hear Freeland's speech here—if you can stomach it.

Let that sink in.

As someone said, "Justin Trudeau does not sound like Adolph Hitler in 1936. But he sounds an awful lot like Adolph Hitler in 1933." Nazi Germany did not get to extermination camps in one step.

I have funds in a local bank that is based in Canada. I have written positively about the Freedom Convoy. Does that mean Canada now thinks it has a right to my money? Can they reach into Florida and grab it, much as Amazon can, if it wishes, reach into my Kindle and yank an e-book I have purchased? We've made an inquiry with the bank's lawyers, but have yet to hear back.

Also from the BBC article:

The Emergencies Act, passed in 1988, requires a high legal bar to be invoked. It may only be used in an "urgent and critical situation" that "seriously endangers the lives, health or safety of Canadians". Lawful protests do not qualify.

And finally,

Critics have noted that the prime minister voiced support for farmers in India who blocked major highways to New Delhi for a year in 2021, saying at the time: "Canada will always be there to defend the right of peaceful protest."

Hypocrites much?