What's the worst part of prepping for a colonoscopy?

Wait. I thought I got over the stomach flu four days ago.

What's the best part?

Two days before Prep Day the diet restrictions are turned on their heads. All those things doctors are always telling us to eat or not eat? Forget about it.

Vegetables, fruits, and whole-grain anything are OUT. Steak, dairy, eggs, ice cream, chocolate, and white bread are IN. Who said gastroenterology was dismal?

Of course, the best part of the whole procedure is that I don't have to think about it again for several more years.

What's the coolest part?

You can stop reading now if this is TMI, but the coolest part was definitely that for the first time I had the procedure done without any anesthesia. I wish I had known of the option earlier, because it. is. so. cool.

A little background.

I don't like anesthesia. By that I don't mean I'm not grateful for its discovery, and its use when necessary. I just think it's overused. In normal childbirth, for example. And during dental work. I especially don't like general anesthesia, which is riskier when you get to my age. I need all the brain cells I can keep. But this is the first time I questioned its use for a colonoscopy procedure.

Before scheduling the appointment, I asked the doctor, more than half expecting him to say no. But he was fine with the idea.

On the day of the procedure, he still was fine with it, though the others in the office gave me every opportunity and encouragement to change my mind. That was a little nerve-wracking, since I'd never done it that way nor had I spoken about it with anyone who had. When the anesthesiologist asked if I wanted him to be there in case I changed mhy mind, I finally said I'd leave it up to the doctor: if he was afraid something might go wrong and wanted anesthesia available, I would agree, but otherwise I was sure of what I wanted. When a nurse asked what I was going to do if it hurt, I replied, "get through it."

The doctor must have trusted me, because I never saw the anesthesiologist again. Apparently I'm not the only one who forgoes anesthesia; it's just rare. And I warn you, it does hurt. But not nearly as much as childbirth, and it's much shorter. You don't get to move, though, and screaming is discouraged. But those breathing techniques never leave you, and the nurse was a great "childbirth" coach.

It's hard to say what I like most about not having slept through the process. Definitely high on the list was what I think it did for the doctor/patient relationship. (And by "doctor" I include all the other medical personnel, too.) I felt part of a team, working together to get the job done. I felt respected as a person and not viewed as an unconscious patient. We interacted throughout the procedure; the doctor explained what he was doing and I was able to ask questions.

The monitor was the absolutely coolest part. They let me keep my glasses on, and I watched from beginning to end (literally). I don't care how many crude comments some people make about where so-and-so's head might be positioned, there aren't many people who have actually seen the inside of their own colons. I have. It's awesome.

Watching was the most fun, but recovery was the most liberating. I wasn't fuzzy-brained. I was in control of my mind and body. Instead of the usual list of all the things I couldn't do for the next day or so (drive, sign legal documents, make important decisions, drink alcohol, eat certain foods), I left with no restrictions at all. I walked to the car instead of being wheeled out in a chair.

(Porter still drove home, and I'm taking the day off. No point in wasting someone's willingness to pamper you.)

Like natural childbirth and forgoing Novocaine at the dentist, skipping anesthesia in cases like this isn't for everyone. But if you're at all intrigued, I encourage you, whenever you're faced with a procedure involving anesthesia, to ask if it can be avoided. Likely the doctor won't suggest it himself—they are so concerned about keeping patients comfortable. But he may be fine with it. It's good to have options.

P.S. Happy Pi Day, everyone!

When it comes to paying out money, I know who "The Government" is. That's you, me, and all other taxpayers out there. Including those overseas who bear the burden of paying taxes to the Federal Government even if their money was earned totally outside of the United States. But that's another issue.

Even as our family watches carefully how our personal money is spent, so we try to be careful that the government's money is spent wisely.

Thus we were concerned when we received a bill from an insurance company we'd never heard of, for a health insurance plan we had not signed up for, assuring us that we owed $0.00 and the government had already paid the full premium of $1375.36 for the first month. I will spare you the details of all the hours Porter has spent on the phone trying to get this cleared up. How do you cancel a policy that can't be found in the system, but for which the government is paying out at the rate of over $16,500 per year? Finally, he wrote an e-mail to the Inspector General.

Mr. Inspector General Levinson,

I am not sure you are the correct person to send my issues to - but hope your office can point me in the right direction if you are not the appropriate channel.

I have two issues, one involving money paid out by the government incorrectly and one involving the difficulty in pursuing such questions via the healthcare.gov team and system.

First, I received a bill from "Florida Health Care Plans" for an ACA plan that I never signed up for, but rather was assigned to automatically by the ACA computers. No one at "Florida Health Care Plans" can tell me how this came to be. Further they say they cannot cancel the policy under the law as they can only do that if healthcare.gov sends them a notice to do so. Further they have no connecting key that can be used by the healthcare.gov team to show how this policy came into existence. When I called the ACA they could not find any trace of this policy with "Florida Health Care Plans." The only policy they show for me is the CORRECT policy I signed up for myself with "Florida Blue," an entirely different company despite the similarity of their names.

The bogus bill shows that the government will pay "Florida Health Care Plans" $1375.36 per month for each month in 2017. I will owe nothing. In other words my payments are to be zero each month. This is the rub. If a "policyholder" does not pay his premium his insurance is cancelled - and the payments from the government to the insurance company would at least stop. However, since I owe nothing each month on this policy there is no trigger to automatically stop payments! The government will be out over $16,000 by the end of the year paying on this bogus, useless policy.

Second issue. Healthcare.gov is not following the ITIL (IT Infrastructure Library) standards. I understand that all federal computing systems are supposed to follow ITIL. When I was a consultant for IBM on the Fannie Mae account this was certainly the case. ITIL provides that all issues should be recorded and a ticket or issue number assigned to them. Further, this ticket number should be given to the person who reported the issue. In my case I should have been given a ticket number so I could reference it in future calls. I was told by the supervisor of supervisors (which was as high as I was permitted to go in my telephone inquiry with healthcare.gov) that no ticket numbers are ever generated, but rather I should wait for a call back from the "Advanced Resolution Center" in 5 to 7 days. I am very doubtful this will happen as in 2016 I got an incorrect "Corrected" 1095a and went through the same process without ever getting the issue resolved.

Please advise how to proceed with these two issues.

Or, I should say, he tried to write the Inspector General. But having sent this to their published e-mail address, he received it back with the following explanation:

Delivery has failed to these recipients or groups:

hhstips@oig.hhs.gov

Your message couldn't be delivered to the recipient because you don't have permission to send to it.Ask the recipient's email admin to add you to the accept list for the recipient.

For more information, see DSN 5.7.129 Errors in Exchange Online and Office 365.

So he respectfully requested to be added, using the e-mail address postmaster@oig.hhs.gov—the sending address for the above rejection. The reply?

How much time would you spend trying to save the United States $16,500? How many bogus charges like this do you think are being made? How many of the people in whose name the government is being billed will put any effort into trying to correct a bill on which they owe nothing?

Stay tuned.

My 95 by 65 swimming goal was very modest: Swim five miles, and brachiate one mile. The reason brachiation was part of the swimming goal will be more obvious when you see the ladder configuration, here demonstrated by some neophytes who are much more fun to watch than I am.

I didn't officially start till July of this year, when I realized that both travel and winter weather would take away a large chunk of the months remaining till my 65th birthday and I'd better pay attention to this goal. But as of yesterday, I'm up to 5.4 swimming miles and 1.3 brachiating. More important, I've established a daily habit: eleven laps (0.1 miles) of the pool, and six of the ladder (0.025 miles). Little steps add up over time!

Now we'll see how long the habit lasts, as the water temperature drops. Thanks to my encouraging daughters, who gave me the new perspective, when I do stop for the winter I will not think of the habit as broken, but rather seasonal, ready to begin again in warmer weather. After all, one does not consider the "skiing habit" broken just because the skis are put away at the end of winter!

Mark and Livy: The Love Story of Mark Twain and the Woman Who Almost Tamed Him by Resa Willis (Atheneum, 1992)

Mark and Livy: The Love Story of Mark Twain and the Woman Who Almost Tamed Him by Resa Willis (Atheneum, 1992)

Mark and Livy was a gift from a friend, who thought I might be interested because Samuel Clemens' wife was a Langdon. As it turns out, we are not related through the Langdon line—unless our common ancestor was back in England and in the 17th century or earlier. The book sat on my shelves until my 95 by 65 project (goal #63) encouraged me to pick it up.

I was going to say that Mark and Livy does not meet my primary criterion for being a "good book": that it inspire me in some way to become a better person. On reflection, however, I realized it has left me with a determination (which needs to be won repeatedly) to be less judgemental of others, especially those of other times and cultures. There are so many advantages we take for granted here and now—and how easy it is to believe that our good characteristics are the outflow of our good character, and not simply because we are not in pain!

Samuel and Olivia Clemens lived in the latter half of the 19th century. They died years before antibiotics were available. They didn't even have aspirin. Common vaccines had yet to be developed. Diphtheria took the life of the Clemenses' firstborn when he was not yet two—as it did so many children of the time. Headaches could last for weeks, and infections linger for months. In an age of great medical ignorance, treatments were often worse than the diseases. It is now known that even three weeks of remaining in bed does terrible damage even to healthy bodies, but at that time bed rest was the go-to cure for everything. As a teenager, Olivia was kept in bed for two years. Even mental exertion was considered harmful and to be avoided as much as possible.

No wonder so many middle- and upper-class women of that time suffered from a malaise sometimes called nervous prostration. With careers and mental stimulation mostly closed to them; with cooks, housekeepers, gardeners, wet nurses, nannies, and tutors doing all the meaningful work around the house; and with every illness sending them into darkened bedrooms, deprived of most human contact (visitors, even beloved husbands, put too much strain on the system)—they were bored out of their minds. And out of their health much of the time as well.

Some things never change: Doctors blamed the problem on the demands of modern life: "...the fast ways of the American people, with their hurried lives, late hours, and varied excesses, wear upon the nervous system of all, especially that of sensitive, impressible women."

Should I be condescending over Mark and Livy's susceptibility to every quack and crackpot philosophy that came down the pike? Needs must when the devil drives.

For more about health and medical care in the 19th century, don't miss The Luxury of Feeling Good from The Occasional CEO, coincidentally published this morning.

Langdon Clemens, the couple's firstborn son who died young, was considered sickly all his life. He was born a month premature and never seemed to be healthy. It was diphtheria that killed him in the end—it killed many who were otherwise healthy—but the book gives no clue as to what caused him to be "sickly." What struck me, however, was that he was considered "slow" in his development. Perhaps he was, but I'm not convinced by the concerns that he wasn't walking by nine months, nor talking when he was "almost a year old"! What did they expect in those days? And of a preemie who started life a month behind?

Here's a fun fact:

Livy and Clemens felt the need to get away [from Hartford's summer heat]. In July they left for New Saybrook, Connecticut ... where all could enjoy the cool winds off Long Island Sound.

New Saybrook? Old Saybrook I know well enough! But New Saybrook? Where on earth is that? Here's a hint:

...they lodged at a hotel called Fenwick Hall....

New Saybrook, it turns out, is an old name for Fenwick! Here's a bit of its history in a New York Times article from 1995, though it doesn't mention a thing about the best-of-all-Fenwick-houses. Still, it's rather amazing to think that Mark Twain could have walked past where the Maggie P. now stands.

Despite being wealthy enough to vacation at Fenwick, the Clemenses had endless money problems and often lived in Europe because that was less expensive for them. That tells less about Europe than about the difficulties of living up to the expectations of their Hartford social set, I'm afraid. Still, it was fun to read:

Clemens ... walked to the top of the Rigi in the Alps.

We've been there! We did not walk, however. I wonder from which point he started his hike?

Despite the strictures of the day and her onerous social obligations, Livy found some outlet for her considerable intelligence. The best part of her day was when she felt free to teach their children:

After breakfast and after she had given the servants their orders for the day, Livy and her daughters worked diligently in their schoolroom on the second floor. Their studies included German, geography, American history, arithmetic, penmanship, and English, with some extra diversions of tossing beanbags, gymnastics, and sewing. [The girls were five and seven at the time.] If they finished their lessons before twelve-thirty, Livy read to them. [Clara] at five and eager to please, knew all the answers but often got her questions confused. When her mother asked, "What is geography?" she replied, "A round ball." When asked what was the shape of the earth, she replied, "Green."

Moreover, Livy was Mark Twain's most important editor, smoothing off the rough edges of the wild writer from the West and making his books acceptable and marketable.

This she far preferred to her social responsibilities as the wife of a famous author and the scion of a wealthy family. (Yes, the Langdons were wealthy—further proof that we're not closely related.)

She increasingly questioned her role as hostess and felt bad because she did.

This is my work, and I know that I do very wrong when I feel chafed by it, but how can I be right about it? Sometimes it seems as if the simple sight of people would drive me mad. I am all wrong; if I would simply accept the fact that this is my work and let other things go, I know I should not be so fretted; but I want so much to do other things to study and do things with the children and I cannot.

In the plus ça change department, do you think we suffer from helicopter parenting today? The Clemenses kept their daughters close in what today would probably be considered an unhealthy relationship of mutual dependence. Further,

[Clemens] insisted his daughters be chaperoned everywhere they went, and Clara was until she married at the age of thirty-five [emphasis mine].

That makes being on your parents' health insurance until 26 seem almost reasonable.

And still more: I'll admit I'm weak in history. I knew about the Great Depression, but if I thought of it at all, saw it as an anomaly, a one-time, terrible event. Thus the economic problems we have been having lately have been particularly concerning. I had no idea, until reading Mark and Livy, how common market crashes, panics, and recessions have been throughout history.

Just as John Marshall Clemens never recovered from the Panic of 1837, this panic [of 1893] nearly destroyed his son. It began who knows where but was aided by a drain on the gold reserve by foreign investors who sold their securities and withdrew them in gold from the U.S. The Sherman Silver Purchase Act, allowing gold to be used to purchase silver, further depleted the federal gold reserve by nearly one hundred million. Gold meant confidence. Without either, the dominoes began to fall. The stock market crash eventually took with it 160 railroads, five hundred banks and sixteen thousand businesses. It was estimated by 1894 that 20 to 25 percent of the work force was unemployed. Those with jobs went on strike to get decent wages as there seemed to be no money anywhere. Miners across the nation refused to work. Eventually the Langdon coal mines and Livy's income shut down.

Rich or poor, black or white, first- or third-world, centuries ago or yesterday morning: our tragedies and our trials, our worries, our hopes, and our joys are more universal than not.

We are humanity.

Ten years ago I discovered xylitol and the positive effects it had on the health of my gums. Four years later I reported on my unintentional experiment in which I discovered that regular use of xylitol in my dental care routine kept my teeth in better shape than they had ever been.

I'm still a huge proponent of xylitol, but today I must report an important caveat: be careful to check the ingredients of any xylitol product you use.

For years I had swished pure xylitol around in my mouth before going to sleep at night—and sometimes during the day as well. That led to a huge dental health victory for me. But I was concerned that most xylitol comes from China, and I try to avoid food products from there if possible, because of their many known abuses. So I was excited to discover a North American-based source of xylitol, and even more so because they also sold xylitol mints and candies that were both more convenient and more interesting than plain xylitol.

Then the reports from my dentist started going downhill, and I was having to have crowns replaced that should have lasted for years, because of decay at the gumline. My dentist was dumbfounded, and so was I. Then I looked at the ingredients list on my xylitol candy packages. Many seemed fine—if flavorings alone caused problems, they would not be in toothpaste. But it turns out that some of the candies, particularly the fruit-flavored ones, also include citric acid.

There may be other factors that led to my dental problems, but certainly it could not have been good to be bathing my teeth in citric acid at night, particularly since I would let the candies disolve slowly in my mouth as I fell asleep, and would also reach for them in the middle of the night to calm a dry cough. After all, it's not so much the bacteria that cause dental caries, but the acid created by the bacteria.

So I'm back to using pure xylitol for my teeth, and taking care to avoid the xylitol candies and mints that contain citric acid. I share this for everyone, including my own grandchildren, who chew xylitol mints as part of their nightly routine, because their dentists have recognized the value of xylitol for dental health. It's still a great idea—but have a care for the other ingredients.

The Power of Habit: Why We Do What We Do in Life and Business by Charles Duhigg (Random House, 2012)

The Power of Habit: Why We Do What We Do in Life and Business by Charles Duhigg (Random House, 2012)

After reading this book, I have the uneasy feeling that it is sometimes oversimplified and doesn't tell the whole story. It is, however, heavily documented—when I read the last sentence of the text my Kindle told me I was merely 75% through the book—and anyone who wants to take the trouble to dig further can do so. More importantly, anyone who wants to test out Duhigg's theories of the power of our habits can easily experiment in the laboratory of his own life.

There's a lot in The Power of Habit that will be familiar to the circle of my readers who are working hard on personal change and challenge. We already know the importance of habit and routines, of baby steps and small wins. But Duhigg's numerous examples and summaries of scientific research are valuable and inspiring.

Our habits aren't just part of our lives—they are what make the rest of our lives possible. Habits are the infrastructure that takes care of the basics and frees our brains for higher work. As habits become part of our brain's structure, they make the difference between sounding out c-a-t and enjoying a novel, between learning to drive and toolin' down the highway.

So habits are good. Well, good habits are good. But the brain doesn't distinguish between good and bad habits. (I'm not sure that's true. Why else would a good habit take weeks to establish but a bad habit seems to stick after a few days?)

Good or bad, habit formation has a basic structure:

This process within our brains is a three-step loop. First, there is a cue, a trigger that tells your brain to go into automatic mode and which habit to use. Then there is the routine, which can be physical or mental or emotional. Finally, there is a reward, which helps your brain figure out if this particular loop is worth remembering for the future.... Over time, this loop—cue, routine, reward; cue, routine, reward—becomes more and more automatic. The cue and reward become intertwined until a powerful sense of anticipation and craving emerges. Eventually ... a habit is born.

And it never really goes away. It's always there, in the brain. That's good, because it means that after falling out of a good routine we can get back in less time than it took to establish it. But it also means that the bad habits we thought we had conquered are lurking there, ready to ensnare us again if we aren't wary.

Habits aren’t destiny. ... [H]abits can be ignored, changed, or replaced. But the reason the discovery of the habit loop is so important is that it reveals a basic truth: When a habit emerges, the brain stops fully participating in decision making. It stops working so hard, or diverts focus to other tasks. So unless you deliberately fight a habit—unless you find new routines—the pattern will unfold automatically.

The Golden Rule of Habit Change: You Can’t Extinguish a Bad Habit, You Can Only Change It.

How is this accomplished? By following the cue, which triggers the bad habit, with a different routine, but the same reward. It's a little more complicated than that, or the book would be a lot shorter. One important factor is identifying what is truly rewarding the action. Do I eat a doughnut every morning because I'm hungry, or because I crave sugar, or because it provides an excuse for socializing with my coworkers? Only when you know what the reward provides can you determine an appropriate good routine to replace the one you want to eliminate.

[H]abits are so powerful [because] they create neurological cravings.

[C]ountless studies have shown that a cue and a reward, on their own, aren’t enough for a new habit to last. Only when your brain starts expecting the reward—craving the endorphins or sense of accomplishment—will it become automatic to lace up your jogging shoes each morning. The cue, in addition to triggering a routine, must also trigger a craving for the reward to come.

More good news lies in the concept of keystone habits. It turns out that very often changing one habit, conquering one problem leads in a domino effect to victories in other areas.

The habits that matter most are the ones that, when they start to shift, dislodge and remake other patterns.

Keystone habits offer what is known within academic literature as “small wins.” They help other habits to flourish by creating new structures, and they establish cultures where change becomes contagious. ... A huge body of research has shown that small wins have enormous power, an influence disproportionate to the accomplishments of the victories themselves.

Keystone habits say that success doesn’t depend on getting every single thing right, but instead relies on identifying a few key priorities and fashioning them into powerful levers.

Once people learned how to believe in something, that skill started spilling over to other parts of their lives, until they started believing they could change. Belief was the ingredient that made a reworked habit loop into a permanent behavior.

Making your bed every morning is correlated with better productivity, a greater sense of well-being, and stronger skills at sticking with a budget. It’s not that a family meal or a tidy bed causes better grades or less frivolous spending. But somehow those initial shifts start chain reactions that help other good habits take hold.

“If you want to do something that requires willpower—like going for a run after work—you have to conserve your willpower muscle during the day,” Muraven told me. “If you use it up too early on tedious tasks like writing emails or filling out complicated and boring expense forms, all the strength will be gone by the time you get home.”

For almost all our married life, we have kept track of every penny earned and spent. It's the best way we know of to learn where our spending habits are on track and when they're veering off into trouble. I've always been surprised at how few people do that—even people who have far more cause to be concerned about money matters than we do. I mention it because that exercise turns out to be one of the ones researchers have used for building "willpower muscles."

Participants were asked to keep detailed logs of everything they bought, which was annoying at first, but eventually people worked up the self-discipline to jot down every purchase.

As people strengthened their willpower muscles in one part of their lives—in the gym, or a money management program—that strength spilled over into what they ate or how hard they worked. Once willpower became stronger, it touched everything.

An important concept in strengthening willpower is recognizing inflection points—situations in which one is most vulnerable to temptation—and creating a plan to deal with them. Then rehearsing the desired response to the point where the temptation cue triggers the healthy action.

This is how willpower becomes a habit: by choosing a certain behavior ahead of time, and then following that routine when an inflection point arrives.

A better response to apparent failure (backsliding, falling off the wagon, slipping out of one's organizational routine yet again) is also critical:

Studies suggest that this process of experimentation—and failure—is critical in long-term habit change. Smokers often quit and then start smoking again as many as seven times before giving up cigarettes for good. It’s tempting to see those relapses as failures, but what’s really occurring are experiments.

If you choose pressure-release moments ahead of time—if, in other words, you plan for failure, and then plan for recovery—you’re more likely to snap back faster.

There is much, much more to The Power of Habit than personal change. That is only Part One. Parts Two and Three are about the habits of organizations and societies. That I'm skipping lightly over them in this review does not mean they are uninteresting or unimportant. If you want to know more about the news story that broke a while back, in which Target knew, from her buying patterns alone, that a teenage girl was pregnant (including her approximate due date) before her family did—this is the place.

And it was here that I finally learned the sad, sad story of Febreze. Proctor and Gamble serendipitously discovered a chemical that could actually eliminate odors, removing the cigarette smell from clothing, and pet odor from carpets, instead of simply masking them.

P&G, sensing an opportunity, launched a top-secret project to turn HPBCD into a viable product. They spent millions perfecting the formula, finally producing a colorless, odorless liquid that could wipe out almost any foul odor. The science behind the spray was so advanced that NASA would eventually use it to clean the interiors of shuttles after they returned from space. The best part was that it was cheap to manufacture, didn’t leave stains, and could make any stinky couch, old jacket, or stained car interior smell, well, scentless.

But it didn't sell, because people don't notice the stinks closest to home. The product was almost trashed, until P&G gave it a strong scent.

[A]fter the new ads aired and the redesigned bottles were given away, they found that some housewives in the test market had started expecting—craving—the Febreze scent. ... “If I don’t smell something nice at the end, it doesn’t really seem clean now."

“We were looking at it all wrong. No one craves scentlessness. On the other hand, lots of people crave a nice smell after they’ve spent thirty minutes cleaning.”

And that's why the one bottle of Febreze I bought, many years ago, sat unused after the first spray. I had bought an odor eliminator, or so I had thought, and had ended up with an odor-creater. Yuck. I do crave scentlessness: in my cleansers, in my paper products, in my greeting cards, in anything that's not supposed to have a smell. In my garden I love odors: roses, gardenias, orange blossoms. In my kitchen I love odors: baking bread, bubbling stew, cookies fresh from the oven. But not in my clothing, linens, and carpets!

On a more serious note, consider this response from a major gambling establishment, accused of unethical behavior in the case of a compuslive gambler:

Like most large companies in the service industry, we pay attention to our customers’ purchasing decisions as a way of monitoring customer satisfaction and evaluating the effectiveness of our marketing campaigns. Like most companies, we look for ways to attract customers, and we make efforts to maintain them as loyal customers. And like most companies, when our customers change their established patterns, we try to understand why, and encourage them to return. That’s no different than a hotel chain, an airline, or a dry cleaner. That’s what good customer service is about.…

“But what was really interesting [in an MRI study of gamblers] were the near misses. To pathological gamblers, near misses looked like wins. Their brains reacted almost the same way. But to a nonpathological gambler, a near miss was like a loss. People without a gambling problem were better at recognizing that a near miss means you still lose.”

Gamblers who keep betting after near wins are what make casinos, racetracks, and state lotteries so profitable. “Adding a near miss to a lottery is like pouring jet fuel on a fire,” said a state lottery consultant who spoke to me on the condition of anonymity. “You want to know why sales have exploded? Every other scratch-off ticket is designed to make you feel like you almost won.”

In the late 1990s, one of the largest slot machine manufacturers hired a former video game executive to help them design new slots. That executive’s insight was to program machines to deliver more near wins. Now, almost every slot contains numerous twists—such as free spins and sounds that erupt when icons almost align—as well as small payouts that make players feel like they are winning when, in truth, they are putting in more money than they are getting back. “No other form of gambling manipulates the human mind as beautifully as these machines,” an addictive-disorder researcher at the University of Connecticut School of Medicine told a New York Times reporter in 2004.

If you think all that's scary, try this:

[W]ise executives seek out moments of crisis—or create the perception of crisis—and cultivate the sense that something must change, until everyone is finally ready to overhaul the patterns they live with each day.

“You never want a serious crisis to go to waste,” Rahm Emanuel told a conference of chief executives in the wake of the 2008 global financial meltdown, soon after he was appointed as President Obama’s chief of staff. “This crisis provides the opportunity for us to do things that you could not do before.” Soon afterward, the Obama administration convinced a once-reluctant Congress to pass the president’s $787 billion stimulus plan. Congress also passed Obama’s health care reform law, reworked consumer protection laws, and approved dozens of other statutes, from expanding children’s health insurance to giving women new opportunities to sue over wage discrimination. It was one of the biggest policy overhauls since the Great Society and the New Deal, and it happened because, in the aftermath of a financial catastrophe, lawmakers saw opportunity.

Once you realize what's happening, you see it everywhere. From the Great Depression and the New Deal, to the 9-11 terrorist attacks and the Patriot Act, to school shootings and the campaign against gun ownership, people are frightened and vulnerable in times of crisis. That's when we are most prone to demagoguery, and our leaders most likely to make serious mistakes.

The author actually presents this vulnerability to change in crisis as something positive, a chance for hide-bound corporations to make much-needed changes. To me, it brings new light to the tendency of politicians, activists, and the media to pour incessant hype on every negative event.

While we were visiting New Hampshire, our son-in-law and the older children spent the better part of one day helping another family move into their new home. Their reward for this good deed was to catch a stomach flu, and bring it home to the rest of us.

One by one the children's gastro-intestinal systems gave in. Porter and I took our turns at the end, but the last victim of all was—you guessed it—Heather. I believe there is quite a bit of truth behind the idea of mom-immunity, a constitutional strength that keeps mothers going until their children are on the mend.

But that immunity finally deserted her the day after I came down with the bug myself. Since I was no longer actively vomiting, and the children—now essentially back to normal—were active and needy, I crawled out of bed to see if I could be useful.

But Jon, who had been among the first to get ill and recover, had everything under control, assisted by the older kids—especially Faith: The Nurturing Force is strong in this one. So I gratefully crawled back up to bed.

Where I stayed for the rest of the day.

For a day all I had to do was drag myself between bed and bathroom, and thought that was a difficult enough task. The rest of the time I slept. And slept. And healed.

What a luxury! What a tremendous blessing! What mom ever has this opportunity? Maybe mothers whose children are in school or daycare can get a few hours' rest, but outside of those hours they too spend more time functioning than healing. Babies need nursing, and children—especially children who have recently been sick themselves—sometimes need Mom's attention, despite the avaiability of other helpers.

Then there are those whose job situations leave them little choice but to drag themselves out of their sickbeds and into a full day's work—to infect who knows how many others along the way.

Wouldn't it be so much better for everyone if our life situations had enough slack built into them to allow all sick people the time to heal effectively?

Cure: A Journey into the Science of Mind over Body by Jo Marchant (Crown Publishers, 2016)

Cure: A Journey into the Science of Mind over Body by Jo Marchant (Crown Publishers, 2016)

Jo Marchant is a scientist and a skeptic when it comes to alternative medicine, but could not deny the anecdotal evidence of its successes. In Cure she documents the efforts of researchers to figure out just what is going on with that, and concludes that the interaction of our minds and our bodies is a lot more complicated than we currently understand.

The placebo effect, and its evil twin, the nocebo effect, turn out to be much more powerful than initially believed, creating observable, measurable changes in our brains, and there are several ways to trick our minds into healing our bodies, some of them bordering on the absurd: people can be healed by placebo pills even when they know they are placebos, even when they know the capsules they are swallowing are filled with nothing but air.

Hypnosis is fighting its way back from its circus sideshow beginnings and proving to be a powerful tool, especially in pain relief and autoimmune disorders. Meditation, too, is shedding its spiritual roots and looks promising for physical as well as mental problems. So does biofeedback. Virtual Reality therapy can apparently do a better job of controlling acute and chronic pain than high doses of addictive drugs.

As medical practitioners are pressed more and more to cut the time they spend with patients, evidence is mounting that health outcomes are greatly improved by listening, caring, reassurance, and ditching the traditional doctor-patient relationship for one in which the patient is considered a full partner in his health care. Family, friends, and social support also have a tremendous impact on health.

Cure is a fascinating book with two important drawbacks. The first one, the author recognizes: acknowledging the power of the mind to affect the body may lead people—and/or their caregivers—to believe that their real, physical illnesses are "all in their heads"—or worse, that it's their own fault if they don't get well. Marchant hastens to explain that the mind-body interaction is a whole lot more complicated than that. I was reminded of the advice given by a pastor to the woman who reported that people were telling her she could throw away her cane if only she had enough faith. "Next time they tell you that," he advised, "Whack them over the head with your cane and say to them that it only hurts because their faith isn't good enough."

The second problem I doubt Marchant sees herself. But the only section that disappointed me is where she tackled the possible effect of prayer on healing, and abandoned her otherwise balanced and open-minded approach. It shows through clearly that she didn't want to find any consequence of prayer that couldn't be chalked up to the placebo effect or a supportive social situation. Even worse, as is true of many researchers she treats "prayer" as if it were an abstract force independent of the particular faith of the pray-er and of whatever entity is on the receiving end of the prayer. As if the cause of a prayer's effect must be solely inside the person praying, so that there can be no difference whether one prays to Allah, Jesus, Thor, or the kitchen sink. With this weakness in methodology, it would have been better to skip the section on prayer entirely.

Here are a few quotes that stood out:

Big pills tend to be more effective [as placebos] than small ones. ... Two pills at once work better than one. A pill with a recognizable brand name stamped across the front is more effective than one without. Colored pills tend to work better than white ones, although which color is best depends upon the effect that you are trying to create. Blue tends to help sleep, whereas red is good for relieving pain. Green pills work best for anxiety. The type of intervention matters too: the more dramatic the treatment, the bigger the placebo effect. In general, surgery is better than injections, which are better than capsules, which are better than pills. There are cultural differences.... [A]lthough blue tablets generally make good placebo sleeping pills, they tend to have the opposite effect on Italian men.

[T]he placebo effect has a dark side. The mind might have salutary effects on the body, but it can create negative symptoms too. The official term for this phenomenon is the "nocebo effect" ... and it hasn't been much studied because of ethical concerns. ... Nocebo effects are even one explanation for the power of voodoo curses. ... [M]ost of the side effects we suffer when we take medicines are not due directly to the drugs at all, but to the nocebo effect. ... Italian researchers followed 96 men.... Some did not know what drug they were taking, whereas others were told about the drug and that it might cause erectile dysfunction. The percentage of patients in each group who subsequently suffered this side effect was 3.1% and 31.2%.

When we were prescribed Malarone as an anti-malarial, we deliberately did not read about the side effects, although I packed the information sheet just in case one of us started having weird symptoms. I guess that was a good idea.

[P]erhaps the most fundamental lesson from research on placebos [is] the importance of the doctor-patient encounter. If an empathetic healer makes us feel cared for and secure, rather than under threat, this alone can trigger significant biological changes that ease our symptoms.

Unfortunately, despite the public health disaster being wrought by prescription painkillers, there is relatively little research interest in non-pharmacological methods to help people deal with pain.... [P]art of the reason for the lack of enthusiasm is economic. Pain relief is a billion-dollar market, and drug companies have no incentive to fund trials that would reduce patients' dependence on their products.... And neither have medical insurers, because if medical costs come down, so do their profits. ... [T]here's no intervening industry that has the interest in pushing it.

That could be about to change, however. In March 2014, Facebook bought a little-known California startup called Oculus for $9 billion. The company specializes in VR [virtual reality] gaming and has just developed a headset called Oculus Rift, similar in size and shape to a scuba mask. Whereas the VR equipment [used with stunning success for pain relief] costs tens of thousands of dollars, Oculus sells its headsets for just $350 each. That promises to bring virtual reality within reach of ordinary consumers, who will be able to run wireless masks from their tablets or smartphones. ... Developments like this mean that people will soon be able to use virtual reality pain relief ... at home. It also means that virtual worlds are about to get much more sophisticated ... as video game companies throw resources at developing software to go with the new headsets. As well as better games ... that could lead to better pain therapies.... [W]e might soon see pain relief trials funded not by drug companies, but by the gaming industry.

Randomized trials comparing planned home and hospital births are almost impossible to do, because it's not practical or ethical to force women to give birth in a particular place. But there are plenty of large, observational trials.... These studies compare women who choose hospital birth with those who try to deliver at home (regardless of whether they have their babies there or end up transferring to hospital for pain relief or medical intervention). It turns out that simply by choosing home birth, women are less likely to require drugs to induce or speed up labor or relieve pain; less likely to be cut open or to tear; and less likely to need a C-section or instrumental delivery. Their babies are born in better shape and are more likely to breastfeed. ... It seems that when you replace easy access to technology with caring for a woman's emotional state, she and her baby fare much better—not just mentally but physically too. ... [T]he reassurance of someone we trust is not a trivial luxury. The right words can be powerful enough to replace aggressive medical intervention and transform physical outcomes.

All too often when we receive medical treatment, our mental state is seen as a secondary concern, and our role as a patient doesn't go much beyond signing consent forms and requesting pain-relieving drugs. ... The three projects described [in Chapter 7]—midwives supporting women during childbirth; radiologists changing how they talk to patients; and doctors discussing difficult questions with the terminally ill—instead give patients an active role to play. These might seem like commonsense interventions, but they all embody a fundamental (and for our medical system, revolutionary) shift in what it means to care for someone. Medicine becomes not an all-powerful doctor dishing out treatments to a passive recipient, but a partnership between equal human beings. This principle is at the heart of many of the other cases we've seen so far, too.... Instead of medicating their way out of problems with ever-greater doses of drugs and interventions, these medical professionals are harnessing their patients' psychological resources as a critical component of their care. They're doing this for adults and children; for chronic complaints and for emergencies; from birth until death. This approach provides a better experience for patients. It costs less. And it improves physical outcomes. Patients suffer fewer complications, recover faster and live longer.

[E]xperiences of social exclusion or rejection—such as being shunned in a game, receiving negative social feedback, or viewing images of deceased loved ones—activate exactly the same regions of the brain as when we are in physical pain.

The impact of loneliness ... depends not on how many physical contacts we have but how isolated we feel. You might have only one or two close friends, but if you feel satisfied and supported there's no need to worry about effects on your health, [researcher John] Cacioppo tells me. "But if you're sitting there feeling threatened by others, feeling as if you are alone in the world, that's probably a reason to take steps."

The most resilient kids were brought up by firm, vigilant parents.... But crucially, these parents were also affectionate, communicative and highly engaged in the children's lives. ... These kids knew where the boundaries were, and that there would be sanctions for bad behavior. But they also knew this was because their parents loved and cared about them.

I'm not sure why we needed a study to tell us that one.

Western medicine is (rightly) underpinned by science and trial evidence, and to many policy-makers and funders, physical interventions just "feel" more scientific than mind-body approaches do. Bioelectronics researcher Kevin Tracey is now enjoying millions of dollars of private and public funding to pursue his idea of stimulating the nervous system with electricity, even though as I write this, his largest published human study is in eight people. Gastroenterologist Peter Whorwell, by contrast, can't persuade local funding agencies to pay for his [Irritable Bowel Syndrome] patients to receive gut-focused hypnotherapy despite decades of positive trials in hundreds of patients.

At the heart of almost all the pathways I've learned about is one guiding principle: if we feel safe, cared for and in control—in a critical moment during injury or disease, or generally throughout our lives—we do better. We feel less pain, less fatigue, less sickness. Our immune system works with us instead of against us. Our bodies ease off on emergency defenses and can focus on repair and growth.

[R]ather than putting our faith in mystical rituals and practices, the science described in this book shows that in many situations, we have the capacity to influence our own health by harnessing the power of the (conscious and unconscious) mind. If you feel that alternative remedies work for you, I don't see any need to abandon them, especially when conventional medicine does not yet provide all of the same elements. But be critical of the advice that you may be offered by alternative therapists. And give your brain and body some credit. It's not necessarily the potions or needles or hand waving that make you feel better. Consider the possibility that these are just a clever way of pushing your buttons, enabling you to influence your own physiology in a way tha teases your symptoms and protects you from disease.

Or as Michael Pollen famously said, "Be the kind of person who takes supplements—then skip the supplements."

This news ought to be making major headlines: Surgery is not necessarily the best treatment for appendicitis! Granted, the alternative is a heavy course of antibiotics, which also carries risks, but I'd take that over surgery any day. (Just don't forget to eat your yoghurt.)

Ultimately, 102 enrolled in the study. Of those, 37 families chose to have their children treated with at least 24 hours of intravenous antibiotics followed by 10 days of oral antibiotics. The others elected surgery.

A year later, about 76 percent of kids whose family chose antibiotics were still healthy and didn't need additional treatment.

Compared to those who got surgery, the children who got antibiotics also ended up needing an average of 13 fewer days of rest, and had medical bills that were an average of $800 lower.

There was also no significant difference in the number of appendicitis cases that became complicated during surgery or after treatment with antibiotics. Minneci said that shows the treatment options are similar in terms of safety.

The option of antibiotics for simple appendicitis is likely already available in large medical centers for adults with appendicitis and probably a few large centers that treat children, said Jennings, who wasn't involved in the new study.

Minneci said his hospital already offers the option of antibiotics to people with simple cases of appendicitis, and he expects other hospitals to start developing protocols to introduce the option, too.

"I think if a family walks in the ER now and they bring it up, the surgeon should discuss it with them because it’s a reasonable option," he said.

The Upside of Stress: Why Stress Is Good for You, and How to Get Good at It by Kelly McGonigal (Avery, 2015)

The Upside of Stress: Why Stress Is Good for You, and How to Get Good at It by Kelly McGonigal (Avery, 2015)

For a book that has such an important message, and which my read-through has left bristling with sticky notes, this was surprisingly hard to finish. It's equally hard to summarize for this review. I'd hoped that McGonigal's TED talk would be an inspiring summary, so I wouldn't have to say, "read the book." But the talk lacks the details and documentation of the book, and, since it came before the book, lacks several key elements. So I'll say it: "Read the book."

Now, I know that most of you won't, so here's a taste.

Despite everything you've heard, it's not stress that's killing you. What's killing you is believing that stress is killing you. If you see stress as a positive force, it does you no harm. Like grasping the nettle.

Oh, great. So not only is stress killing me, but it's all my fault because I can't make myself pretend it isn't killing me....

Relax. It's not that bad. Really.

As a health psychologist, Kelly McGonigal had made a career out of telling people how bad stress is for their health, and teaching them techniques to help reduce it. But then she came across a study that indicated that by encouraging people to fear and avoid stress, wasn't helping them, but making their lives worse. She might have ignored, or discredited the research, but instead threw herself into investigating this crazy idea, and came away convinced.

In 1998, thirty thousand adults in the United States were asked how much stress they had experienced in the past year. They were also asked, Do you believe stress is harmful to your health?

Eight years later, the researchers scoured public records to find out who among the thirty thousand participants had died. Let me deliver the bad news first. High levels of stress increased the risk of dying by 43 percent. But—and this is what got my attention—that increased risk applied only to people who also believed that stress was harming their health. People who reported high levels of stress but who did not view their stress as harmful were not more likely to die. In fact, they had the lowest risk of death of anyone in the study, even lower than those who reported experiencing very little stress.

The researchers concluded that it wasn't stress alone that was killing people. It was the combination of stress and the belief that stress is harmful. The researchers estimated that over the eight years they conducted their study, 182,000 Americans may have died prematurely because they believed that stress was harming their health.

... According to statistics from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, that would make "believing stress is bad for you" the fifteenth-leading cause of death in the United States, killing more people than skin cancer, HIV/AIDS, and homicide.

But there's good news: very small changes can have a great effect on how we look at stress. A brief lecture on the benefits of stress, ten minutes spent writing about what values we find important; such brief interventions have been shown again and again to have long-lasting effects. This isn't a think-and-get-rich plan, nor a placebo effect, but more of a butterfly effect.

[T]o many, these results sound more like science fiction than science. But mindset interventions are not miracles or magic. They are best thought of as catalysts. Changing your mindset puts into motion processes that perpetuate positive change over time.

A belief with this kind of power goes beyond a placebo effect. This is a mindset effect. Unlike a placebo, which tends to have a short-lived impact on a highly specific outcome, the consequences of a mindset snowball over time, increasing in influence and long-term impact.

I'm very bad at doing the "exercises at the end of the chapter" in any book, but even so, simply reading through this one has already made a difference in my life. How much remains to be seen, but the butterfly has flapped its wings, and I'm looking forward to seeing what happens.

And now for the quotes. Extensive, yes, but I'm still leaving too much out. If you can get the book from a library, as I did, it will be well worth your while; it's repetitive enough that you can skim and get the major points. Is it worth $13 for the Kindle version? I don't know; maybe it depends on how stressed you are.... (More)

I think anyone should be able to get to the Posit Science BrainHQ Daily Spark exercises. At least, the e-mail states,

Every weekday, the Daily Spark opens one level of a BrainHQ exercise to all visitors. Play it once to get the feel of it — then again to do your best. Come back the next day for a new level in a different exercise!

If you try and can get to them without paying (even better if without registering), let me know. Or let me know if you can't. Since I have a subscription, I'm not sure what others see.

I find the BrainHQ exercises interesting and challenging, and I really have to get back to doing them on a regular basis.... (95 by 65 goal #70)

I've written before about Stephen Jepson and his Never Leave the Playground program. Now he has added brachiation to his collection of fitness "toys." Note his interesting form, without the usual swinging action of the body.

Note that Jepson's solution for an easier version while building up strength is very similar to ours, though his also works when the weather's too cold for swimming. I'll have to remember that!

And they wonder why some people take doctors' recommendations with a grain of salt. The same medical establishment that pushes the Back to Sleep campaign and is now spreading panic over measles (though I mostly blame the media for that) has declared our grandchildren to be out of compliance.

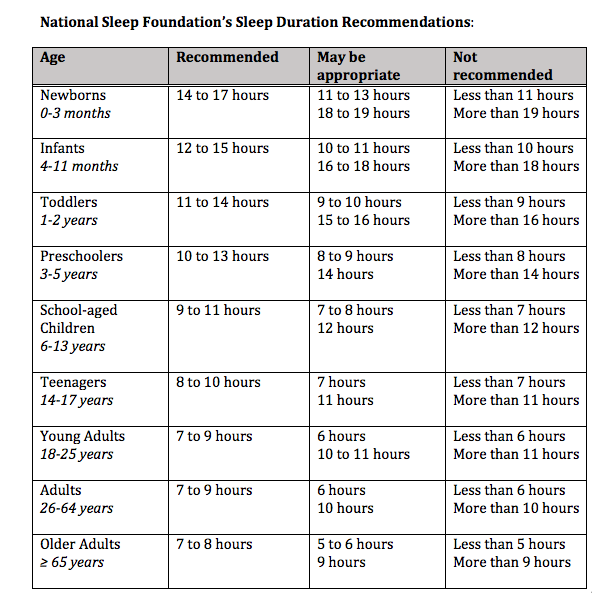

The National Sleep Foundation and the panel of experts has come up with new sleep recommendations for various age groups. To wit:

I'm all for sleep, and agree that most people don't get enough, myself included. But did you catch the recommendations for babies? Newborn to three months, 14-17 hours? Four to eleven months, 12-15 hours? Porter wonders if the doctors are recommending drugs or the ol' baseball bat trick to enforce those limits. I'm pretty sure none of our eight-and-counting grandchildren slept that much in a day. It's possible our own children did, but I was too sleep-deprived at the time to have established reliable memories.

It takes a rich, greedy capitalist to grind the poor into the dust, right? Certainly over the years many have done a very good job of that. Our recent viewing of the documentary, Queen Victoria's Empire, drove home the disastrous consequences of both imperialism in Africa and the Industrial Revolution back home in Britain.

However, the same video also revealed the devastation that can be wrought by someone with good intentions, even against his will (e.g. David Livingstone), and especially when combined with the above-mentioned greed (e.g. Cecil Rhodes).

Which brings me to the point. I cannot count the hours and hours of struggle Porter has put into getting us health insurance in these post-retirement times. Without a doubt, I am personally grateful for the choices the Affordable Care Act (a.k.a. Obamacare) offers us, as much as I philosophically fear its negative consequences. Some of those negative consequences are personal, too: e.g. the colonoscopies that had been covered by our insurance in the past no longer qualify for coverage because of new rules instituted by the ACA. And we can't afford to get sick until after the end of January, because the "helpful" phone contact assigned us the wrong Primary Care Provider, and the fix won't go into effect till February 1. However, I admit to no longer hoping for repeal of the ACA, because the damage has been done. Too many people, including us, are now dependent on it. I doubt we can put the genie back in the bottle.

While I freely acknowledge that the passage of the ACA had at its heart noble ideals and good intentions, I'm not convinced it's really helping the poor, or at least not as much as it's helping people who get rich off the needs of the poor. Porter, being retired, has the time to put into navigating the complex and exceedingly frustrating waters. He also has a degree in economics and a mind well-suited to financial calculations. Which convinces me that the truly impoverished will (1) throw up their hands and settle for a much less than optimal health care plan, or (2) fall prey to those who would profit from doing the paperwork for them, while charging inordinate fees and still coming up with a less than optimal plan.

Nonetheless, the purpose of this post is neither to start a political discussion nor to depress you. It's to honor my husband, for whom Sunday's Animal Crackers comic could have been created:

No doubt about it: I married the right man.

Permalink | Read 3166 times | Comments (0)

Category Health: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Random Musings: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Everyday Life: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Just for Fun: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

The two best things about Geneva, Florida may be our friend Richard and the Greater Geneva Grande Award Marching Band, but thanks to Jon I've discovered a third: Stephen Jepson. Take time to watch this Growing Bolder video. It's less than eight minutes long and will show you why I'm enthusiastic about this 73-year-old man's ideas.

I'm looking forward to exploring his Never Leave the Playground website. After watching the Growing Bolder interview, my only negative reaction was that keeping so mentally and physically fit takes up so much of his time he can't possibly fit in anything else, and few people can (or would want to) live that way. But clearly that's not true—he's an artist, an inventor, and a motivational speaker—and his website promises you can begin with easy baby steps.

I wonder if we've passed him among the spectators at our Independence Day parades. Nah, he'd more likely be in the parade himself. But I'll keep my eye out this year for someone juggling on a skateboard.