One of my favorite Substack people (Heather Heying, Natural Selections) wrote this in her article entitled, "It’s an Upside Down World, and You’re Living In It."

I used to be a Democrat. Two of the things that I did that felt democraty include:

I bought as much of my food as possible at farmer’s markets, and got to know the farmers who grew my food. I bought organic, and avoided GMOs. When given a choice, I bought food that was grown closer to how it had been before humans got involved—cows that had spent their lives grazing outside, coffee grown in the shade on farms with canopy trees, tomatoes and strawberries picked at perfect ripeness, transported as little as possible, eaten fresh and raw.

And I refused pharmaceuticals except when absolutely necessary—the notable exception being vaccines, which I barely questioned until Covid raised my awareness. Over the counter drugs were no better. The rule of thumb in our house was: the longer it’s been on the market, the more likely it is to be safe. Aspirin seemed like a pretty safe bet, as did some antibiotics, in moderation. Everything else? Buyer beware.

I still do these things. My behavior was always informed by an evolutionary understanding of the world, a fundamental preference for solutions that have stood the test of time (e.g. beef over lab-grown meat), and wanting as little corporate product and involvement in my life as possible. Such behavior just doesn’t seem democraty anymore. It seems like the opposite.

In response, I wrote the following.

For decades, I have been saying that the Republicans need to reinvent themselves as the party of human-scale life. Seeing Trump and Kennedy together call to Make America Healthy Again gives me more hope in that direction than I've had in a long time.

Your beautiful, healthy approach to living felt Democrat-y to you, but in my life it has always been embraced by a mixture of folks, from hippies to conservative Christians, who shared a love of what we saw rejected by mainstream society: children and family life; non-medicalized childbirth and homebirth; the critical importance of breastfeeding; independent and home education; the belief that children can be far more competent and responsible than we give them credit for; small businesses; small farms and natural foods; the superior flavor and health benefits of raw milk and juice, pasture-raised animals, and organically-grown fruits and vegetables; homesteading and preserving/restoring the land; reclaiming heritage breeds and seeds; and a deep concern for the environment that was called conservation before it was taken over and ruined by the environmentalist movement.

If the Republican Party will truly embrace and fight for these values, I will in turn be thrilled to have finally become a Republican after 56 years a Democrat. The beginning of the end of my complacency with the Democratic Party was discovering the party's intense opposition to homeschooling—despite the fact that so many of the home education pioneers were radical liberals in their day.

Home education may have been the beginning of my disaffection, but the disconnect between the Democratic Party and the values I thought were their priorities became more and more obvious, accelerating at a most alarming rate, to the point where I agree with Dr. Heying again:

The democrats are claiming that they’re on the side of the little people. The only proper response to such claims is this: No. No you are not. Stop lying. And: No.

Republicans, this is your chance. Don't blow it by infighting, nor by sabotage from within. Reach out to the Independents and disaffected Democrats—like Dr. Heying, and RFK Jr., and Sasha Stone...and me—who are reaching out to you, willing—eager—to put aside our differences long enough to do the really hard work of seeking and saving that which is rapidly being lost.

Permalink | Read 1087 times | Comments (0)

Category Education: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Health: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Politics: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Children & Family Issues: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Food: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Conservationist Living: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Here I Stand: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

Don't be manipulated. Good advice, but very broad, and hard to follow. This post was inspired by what I have read about "bad actors"—AI bots or paid humans—attempting to sow discontent, anger, and hatred online. The Chinese and the Russians have both been accused of this, with what seems to be pretty convincing evidence, and I fear some of it is also homegrown.

My greatest concern is that Artificial Intelligence is rapidly advancing to the point where we can no longer trust our own eyes and ears, at least where online videos are concerned. It is possible to manipulate images and audio to make it appear that someone is saying something he or she never said. Think what political enemies could do with that! Everything from rigging elections to starting World War III. And you know those crazy spam blackmail threats that claim they recorded you doing "nasty things" in front of your computer? The ones you face with a grim smile and quickly delete because you know you never did whatever it is they claim? Imagine them including a video of you "actually" doing or saying what you did not? What if they show you a candidate for public office in that compromising position? Or your spouse, or your children. What about fake kidnappings? I could go on and on—my imagination is fertile and paranoid.

But that's not where I'm going in this post. AI's not quite there yet, and we have a clear and present danger in the here and now: Angry, profane, and hateful comments posted to articles, videos, and podcasts. Nasty online videos (especially the short form commonly seen on Tik-Tok and Facebook Reels) whose purpose (obvious or subtle) appears to be to stir up negative emotions. And that's just what I see every day; I know there's a lot more out there. It's hard not to have a visceral reaction that does no one any good, least of all ourselves.

And that, I'm afraid, is exactly the purpose of what is being posted. To make us angry; to make us suspicious of each other; to influence our reactions, our actions, our purchases, and our votes.

The best solution I've been able to come up with (and I have no idea how effective it might be, except with me) is this:

- Know your sources. Is this negativity coming from someone you actually know, in person, so that you are aware of the context? Is it from someone you know online only, but have had enough experience with over time to assess his general attitude, reliability, and track record? If not, keep your salt shaker near.

- When in doubt, if the content tempts you to react badly, assume the best: It's a bot or troll whose purpose is to make you angry; or a human tool too desperate for a job to consider its moral implications; or an ordinary human being who has been having a bad day/week/year (doesn't that happen to all of us?). In any case, make an effort not to fall into the trap.

- Avoid sources that usually make you react badly. Unfortunately, I don't think we can afford to avoid seeking information about what is happening in the world. One of the first rules of self-defense is to be aware of your surroundings. But we can be cautious. Even the sources I find most reliable can have nasty trolls in the comment section, so I mostly avoid reading the comments. I'm also trying to wean myself off of the Facebook Reels (mostly ported over from Tik-Tok or Instagram it seems). They can be fun, and funny, and sometimes usefully informative. But they are definitely addictive, and I've noticed that far too many of them are negative, even if humorous, leaving an aftertaste of fear, anger, disgust, and/or suspicion. Not good for the human psyche!

- Consider slowing down? I'm struggling with this one, because of the reality that so much of our information comes in video form these days. Unlike print, in which it is easy to skim for information, to skip over irrelevant sections, and to slow down and reread what is important, and which provides a much better information-to-time-spent ratio, the best one can do with video is to speed it up. I find that almost everything can be gleaned from a video just as well if it's taken in at 1.5x speed, sometimes even 2x. Porter's ears and brain can manage 2x almost all the time. This is a blessing when there is so much worth watching and so little time! However, here's what I'm struggling with: videos watched at high speeds tend to sound over-excited, even angry, when at normal speed they are not. And the human nervous system is designed to react automatically to such stimuli in a way that is probably not good for us if we are not actually in a position to either fight or flee. I don't have a satisfactory answer for this, but I figure it's at least worth being aware of.

- Remember that the people you interact with online are human beings, who work at their jobs, love their families, and want the best for their country, just as you do. Unless they're not, in which case it's even more important not to rise to the bait.

Be aware, be alert, do what is right in your own actions and reactions, and hope for the best. It's healthier for us all.

Permalink | Read 1068 times | Comments (0)

Category Hurricanes and Such: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Health: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Politics: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Random Musings: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Everyday Life: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Social Media: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

I think we all need some good news this morning, completely free of political angst.

Dark Chocolate May Be Good for the Eyes, Study Says

As with most Epoch Times articles, this may require an e-mail address to see, even though it's free. So I'll quote a few relevant sections.

Researchers from Italy found that eating just a few squares of dark chocolate—around three from a standard bar—could improve how well the blood vessels in your eyes work. These vessels are essential for maintaining clear and healthy vision.

It found that consuming dark chocolate significantly widened the blood vessels in the retina when exposed to flickering light. This widening improves blood flow, allowing the retina to receive more oxygen and nutrients, which helps it function properly.

[Lead author Giuseppe] Querques, who is also a professor of Ophthalmology at the Università Vita-Salute San Raffaele in Milan, said that this suggests that dark chocolate might help prevent eye diseases and could have broader health benefits, as the effects seen in the eye’s blood vessels might reflect how cocoa affects the rest of the body.

According to Queques, dark chocolate helps increase the production of nitric oxide, which makes blood vessels in the eyes widen more. The plant compounds in dark chocolate boost the amount of nitric oxide in the body, leading to greater dilation of retinal vessels.

Note that nitric oxide has many other heath benefits, and you can get it from sunshine as well as from chocolate. Also, beets. Two out of three....

Querques added that if further studies confirm that regular dark chocolate consumption plays a favorable role in preventing or managing retinal diseases, “daily cocoa intake could be used as a therapy or prevention not only of retinal but also of systemic diseases.”

I note with special pleasure that this is the first article I have read that speaks of the benefits of eating dark chocolate without feeling obligated to add, "But we all know chocolate also contains bad things like fat and sugar, so we don't recommend eating it."

This morning I posted Jordan Peterson's take on the disastrous fall from grace of America's once-trusted institutions: government, academia, the media, and medicine. By the time evening came around I had also found Jeremy Tucker's point of view, with similar conclusions. It's an Epoch Times article, so I'll quote a few paragraphs for you.

Several new polls have appeared that confirm what you suspected. Trust in medical authority and pharmaceutical giants, along with their core product, have hit new lows.

People were willing to go along [with the government's COVID policies], simply because most people presumed that there had to be something true about the fears or else leaders would not be saying and doing such things. Surely, too, if this fear was being exaggerated, certainly the medical profession would have been the first to blow the whistle. Instead, we saw media, medicine, government, and pharma all marching in lockstep as the economy was crushed and civil liberties were wrecked.

It seems strange and bitterly ironic that following the largest and most expensive public health intervention in human history that trust would have sunk so far and so dramatically and is unlikely to recover for a generation. That is a problem that needs addressing. It certainly cannot be swept under the carpet, and the dissidents certainly should no longer be treated as problems to silence.

The people who expressed grave doubts about lockdowns and vaccine mandates should be given a hearing and spotlight. They were correct when the entire establishment was wrong. We might as well admit it. That is the beginning of the restoration of trust.

Every important question is complex.

I'm as appalled as anyone at the irreversible mutilation being done to children by their parents and their doctors, under the guise of "gender-affirming care"—a term that's as bizarre an example of doublespeak as George Orwell ever dreamt of. Parents and doctors, abetted by teachers! Three of the strongest forces in life charged with keeping children safe! Surely this inversion of reality is one of the greatest horrors of our day.

And yet. And yet. It doesn't take much thinking to realize that societies, over all time and all places, have had a very inconsistent view of what, actually, is considered mutilation.

As a child, I remember seeing pictures (probably in the National Geographic magazine) of African women with huge wooden disks in their lips or ears, their bodies having been stretched since childhood by inserting disks of gradually increasing size. I called it mutilation; they called it fashion.

Not that many years ago, the Western world was horrified by the practice in many cultures of female circumcision, dubbing it "female genital mutilation," and putting strong negative pressure on countries where it was common. As recently as 2016 we saw billboards in the Gambia attacking the practice, and I was in agreement. But who was I—who is any outsider—to burden another culture with the norms of my own? Cultures can and sometimes should change, but from within, not imposed by outsiders.

What about male circumcision? That has been practiced for many millennia, in divergent cultures, and is far less drastic than the female version. If we'd had sons, I don't think we would have had them circumcized, there being no religious reason to do so—but when I was a child, it was the norm for most boys in America, regardless of religious affiliation. By the time my own children came along, there was a strong and vocal movement to eliminate male circumcision. Where are those folks now, when we are routinely removing a lot more than foreskins?

Okay, how about piercings? Tattoos? Frankly, I call both of them mutilation. Obviously, a large number of people disagree with me.

Some cultures in the past had no problem with "exposing" unwanted babies, leaving them to die—unless some kindly, childless couple found them and raised them as their own, thus creating the foundation for centuries of future folk tales and novels. We in America can hardly cast stones at those societies, given how few of our own unwanted babies live long enough to have a chance to be rescued.

Where do you draw the line? Maybe between what adults do of their own free will, and what adults do to children who are not yet capable of making informed decisions? Yet there are parents who have the ears of their babies pierced, or disks put into their lips, or parts of their genitals removed, and the societies they live in have no problem with that.

Where do you draw the line? I agree it's a complex and difficult issue.

All I know is that if America has become a place where parents, doctors, and teachers—those we trust most to do no harm to children—are facilitating the removal of young children's genitals, flooding their bodies with dangerous drugs, and encouraging them to believe that this is the best course of action for their mental health, then we haven't just crossed a line—we've fallen off a cliff.

Permalink | Read 1114 times | Comments (3)

Category Health: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Politics: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Children & Family Issues: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Here I Stand: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

The Kindle version of Robert F. Kennedy, Jr.'s blockbuster book, The Real Anthony Fauci, is currently on sale at Amazon for $1.99. I don't thnk Kennedy is the right man to be president at this point, though I would have voted for him in the primary, if I'd had the chance. But that doesn't change the fact that I believe everyone should read his book.

Here's my review, and a couple of short videos about the book. If you're at all interested, you can't beat the price.

With good reason, we have been focusing here on Grace. But there's another half to this bone marror transplant, and that's her sister-donor, Faith. They were a perfect bone-marrow match, and Faith was delighted to be able to provide this life-saving gift to her little sister.

But it has not come without significant sacrifice, and I daresay insufficient preparation. The bone marrow transplant literature makes it out to be a much lighter procedure than it is. The pre-donation testing is rigorous and extensive—Faith fainted at one point—and the donation itself involved forty-seven separate insertions of the needle into her bones! (Possibly twice that many; I don't remember if that number was total, or for each side.) They had made so little of the strenuousness of the procedure that Faith had hoped to be able to join her friends on a ski trip a few days afterwards—not to ski, of course, but to sit in the lodge and enjoy the camaraderie and atmosphere. That was so far from the reality that I question whether "informed consent" was taken seriously.

Here's what happened, and is happening, according to Jon's most recent post:

When Faith signed up for the donation, she was told to expect one or maybe two days of significant pain, and then a week of pain that should be managed with Tylenol and then no running and jumping for six weeks, even if she felt like it.

She had 3-4 days of significant pain, and has certainly gotten better since the first week, but at more than 4 months, continues to have 2 out of 10 pain 24 hours a day. And more pain if she exerts herself too hard.

Grace's doctors referred Faith to her primary care, who took some x-rays and referred her to physical therapy. The x-rays didn't show any fractures. The physical therapist didn't really know what to do, in that she didn't know anything about bone marrow donation, but asked a bunch of good questions and gave her some exercises to do daily. She is supposed to go back to her primary care if she is still in pain in a month or two. We did find on Google that 4% of donors are still in pain at 9 months and 1% are in pain at 12 months, but the cancer doctors said that Faith shouldn't be in that class of donors, since she is so young. We do wonder if the "hard time" the doctors had when collecting the bone marrow would result in this extra pain, but we don't know.

Faith wants to play soccer in the fall, but if the pain continues, will not be able to. She would appreciate your prayers as she tries to rest, but also work on getting her body ready for soccer.

I know Faith, and I know that she would have made the donation anyway, even if she had known the consequences. But facilities that do bone marrow transplants should be paying more attention to the donors, who are an absolutely essential part of their cancer treatment process. Shouldn't there be someone on staff who knows about the consequences and complications, and can do more than send her back to a primary care doctor who undoubtedly knows little to none of that? I have great respect for physical therapists, and this one sounds good, but they don't have this specialized knowledge.

When you pray for Grace (thank you!) would you please also pray for Faith? For wisdom for her, her parents and the doctors; for complete healing; and that she will be able to get fully back to normal life (and soccer!).

A family member was feeling chronically tired, unusual for someone of her age and apparent health. Suspecting anemia, the doctor did some blood tests. Lo and behold, her iron levels were fine—but she was deficient in vitamin D! From what I've heard, that's not unusual for Americans, especially those who live in the northern parts of the country. I grew up knowing that vitamin D was important for preventing rickets, a disease I had mentally relegated to history, like smallpox and scurvy. (I actually thought about smallpox more frequently than rickets, since I am of the last generation to receive routine smallpox vaccinations.) However, it turns out that vitamin D is essential for a lot more than that, including a healthy immune system. As with nearly everything health-related these days, there's controversy over how much is needed, but one thing is clear: many of us are deficient, and could safely use a lot more than we are getting now.

I find it interesting that the tests my doctor orders for every annual exam, which check my blood for multitudinous levels of this and that, do not include measures of vitamin D, or any other vitamin for that matter. Not that I'm worried about D in particular, given that we live in Florida. There's no doubt in my mind that the best way to obtain vitamin D is through exposure of our skin to the sun (don't tell my dermatologist I said that), not only because it is the most natural (there are not many un-fortified food with a lot of vitamin D), but because sunlight exposure produces other substances important to health, such as nitric oxide.

Let's see: For many decades, Americans have been increasingly avoiding the sun, spending nearly all our time indoors, and slathering ourselves with sunscreen when we are not. We have also been cutting down our intake of some of the best natural food sources of vitamin D: egg yolks, red meat, and liver, with fatty fish being about the only good source we're not encouraged to eat less of. (I'm certain it's not coincidental that fatty fish has throughout history been a popular food in lands where it's difficult or impossible to get sufficient vitamin D through sun exposure.) It's no wonder that we have a hidden epidemic of vitamin D deficiency!

I've always wondered why breast milk is apparently deficient in vitamin D, which is why babies who don't get fortified formula are routinely prescribed supplements. It doesn't seem right that the system designed for a baby's best nutrition should be so lacking. I can think of two possibilities: (1) mothers are themselves deficient, and thus can't provide what their babies need, and/or (2) in cultures with sufficient sunlight, babies have for millennia spent a great deal of time outdoors, naked or nearly so, and thus would be making their own vitamin D.

Florida is a good place for getting all the sun exposure we need. However, we too spend most of our time indoors, and shouldn't be complacent. When it was recommended from a couple of independent sources, I decided to download the dminder app on my phone. It's pretty simple, and lets me keep track of my vitamin D intake, from food, supplements, and exposure to the sun. In my case, the first two pale in comparison with the last, at least at this time of year.

Taking into account skin tone, clothing, weather, latitude, elevation of the sun, and time of exposure, dminder calculates approximately how much vitamin D I'm making through my skin for each exposure session (at least those for which I remember to start the app).

A few interesting observations:

- For the purpose of making vitamin D, there's no point to sunbathing except between the hours of 8:56 a.m. and 5:54 p.m., because the elevation of the sun is not sufficient at other times. (The hours change, of course, with latitude and the changing of the seasons.)

- Solar Noon at the moment is actually 1:25 p.m., thanks to our propensity for meddling with the clocks.

- In the present season, during which I wear shorts and a t-shirt, in the middle of the day I can easily generate 2000 IU's of vitamin D during a mere 25-minute walk around the neighborhood!

I will be interested to see what dminder has to say about the summer sun in New England.

I couldn't resist posting this Future Proof video, because my husband is obsessed with flavored sparkling water, and our grandchildren love it, too—probably because they're allowed to drink more of it than they are allowed soda. Special note to said husband: check out this guy's favorite brand (9:17).

(14 minutes on normal speed, mild language warning. I am, by the way, really annoyed by the objectionable language that finds its way into so many YouTube videos. It would probably be easier to note when there isn't bad language. Good ol' YouTube, for whom "free speech" means you can swear to your heart's content as long as you refrain from expressing unfashionable opinions.

You need to get out of your comfort zone.

How often have you heard that advice? Or given it?

It sounds good, as do most dangerous ideas that contain a bit of truth.

Doing hard things can lead to physical, mental, and spiritual growth. But it can also break you. Children grow best when we give them plenty of opportunity to stretch their abilities—not by subjecting them to the rack. That goes for adults, too.

Here's the thing: For many people, living ordinary, daily life is out of their comfort zone, and they get all the growth opportunities they need just making it through the day. Let me say that again.

For many, daily life is out of their comfort zone.

I guarantee that you know people for whom that is true. It may very well be true for you; if not all the time, at least on occasion. The catch is, none of us knows where someone else is in this. We have no idea how hard someone may be working to make it seem as if his life is easy—or even bearable. And that's okay. Life is hard, and growth comes out of the struggle. As long as we remember that it's not our job to push someone else out of his own comfort zone. I know a woman who learned to swim by being thrown out of a boat in the middle of a lake. A lake with alligators. She lived, but I don't recommend the method.

In my experience, when someone tells another person, "You need to get out of your comfort zone," he's less interested in helping that person grow than in getting a particular job done. And hoping that a combination of guilt and the prospect of personal growth will push the reluctant victim to accept. Don't do that.

Push yourself? That's great. Reaching, stretching, working hard, and overcoming difficulties can be good for you and for the world—and it usually feels fantastic (in the end; not always in the middle). But when someone else insists you need to get out of your comfort zone, take it with a grain of salt. Sometimes pain can indeed lead to gain, but it is more likely to lead to injury. And for sure, don't say such a thing to others.

Comfort zone? Comfort zone? Where does that idea come from, anyway? I'll take a poll: Who here are feeling relaxed and comfortable with their lives? Raise your hands. I didn't think so.

There's work to be done in this world, and duty calls us all. Difficult tasks and decisions come to us every day, nolens volens. This is not a call to shirk our responsibilities, but to know ourselves and to respect the needs of our fellow-strugglers.

I've lost much of my faith in the New York Times, the motto of which seems to have evolved from "All the news that's fit to print" (first generations) to "All the news that fits, we print" (my generation) to "All the news we think you're fit to hear" (now). Still, I think they might have gotten something right in this recent article: Morning Person? You Might Have Neanderthal Genes to Thank. If you find that behind a pay wall, here's the relevant part:

Neanderthals were morning people, a new study suggests. And some humans today who like getting up early might credit genes they inherited from their Neanderthal ancestors. The new study compared DNA in living humans with genetic material retrieved from Neanderthal fossils. It turns out that Neanderthals carried some of the same clock-related genetic variants as do people who report being early risers.

I'm not surprised. Supposedly, I have more Neanderthal genes than 91% of all those who have been tested by the popular 23andMe system. And I'm definitely a morning person. I generally wake up naturally between 4:00 and 5:30 a.m. bright-eyed-and-bushy-tailed. "Sleeping in" means sleeping till 7; that's rare, and generally doesn't happen unless I'm sick ir out of town. I'm not sure why the latter changes my sleep patterns; I'm sure it's part the change in daylight hours, and in part that my routines have been interrupted. In any case, I do my best work in the morning, and unless I'm hot-and-heavy into some interesting work, I'm pretty much useless after 9 p.m.

The odd thing is that I didn't discover my morning-personhood until later in life. Clearly environment has a strong effect. My parents were much more night owls than I am, routinely staying up past 11 p.m., which influenced my own bedtime. And a life ruled by prime-time TV hours (8 p.m. to 11 p.m.) and morning alarm clocks (school or jobs) is automatically a life of disrupted circadian rhythms.

It was our children who introduced me to the joys of the early morning hours. I didn't realize it so much at the time, as they also introduced me to the phenomenon of chronic sleep deprivation. I was getting up early, but also staying up late. As every parent knows, when you have children, that slice of time we like to call "our own" diminishes drastically. Our kids may have been in bed by eight o'clock, but I habitually stayed up until 11 simply because it was the only time I could do any kind of concentrated work. Not that you could call it quality time for the way my brain works, but I tried.

Thank you, dear Neanderthal ancestors, for giving me the genes to enjoy God's beautiful mornings. It's great to finally be in a position where I can take advantage of them. I could insert here a rant against Daylight Saving Time here, but you already know how I feel about that!

I've long known, and been troubled by the fact that nearly all of our vitamin C comes from China.

It's not that I'm against trade with China. When two powerful enemies have a thriving trade relationship, they are much less likely to seek to blow each other to bits.

On the other hand, China's terrible reputation when it comes to health and safety, environmental, labor, and human rights concerns really ought to be taken more seriously, especially when it comes to what we ingest.

I'm sufficiently convinced of the value of vitamin C in preventing/mitigating illness that it's a regular part of my health routine. As I said to one of my doctors, who agreed that he followed a similar philosophy, "I don't care if it's only the placebo effect—the placebo effect itself turns out to be effective about a third of the time." For that reason, I've been seeking a non-Chinese alternative to vitamin C.

I think I've found one: LifeSource Vitamins.

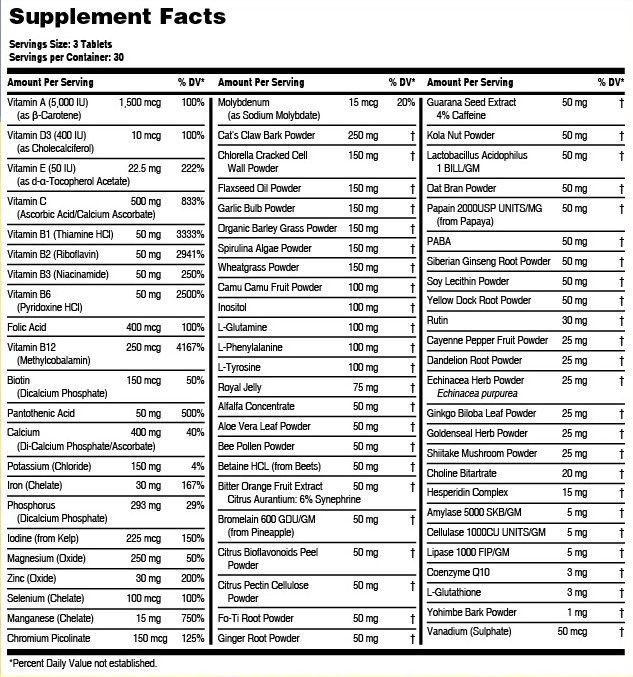

It from no one's recommendation, no advertisement, nothing but a simple internet search on "vitamin c not from China." So this is not a review, nor an endorsement of all they offer. But their vitamins do not come from China, and what's more, they're local (just across town in Winter Park). That was good enough for me to give them a trial. I ordered their 500mg vitamin C, and also decided to try some multivitamins and minerals. The latter is a whole lot more than just vitamins; I reproduce the back label here, not only for your information, but so I can easily read it when I want to; to read the actual label I have to resort to a magnifying glass.

I have no idea what good all these various things are supposed to do for me. (Chlorella Cracked Cell Wall Powder, anyone?) I'll let you know if I can suddenly leap tall buildings in a single bound. I'm more interested in the more ordinary ingredients, and will note that the "serving size" is three tablets (you're supposed to take one with each meal), so if some of these percentages look a little high to you, it's easy to take just one.

And that's another thing I like about these vitamins: they are easy to take, period. I don't generally have trouble swallowing pills, but often have a real problem with vitamin C tablets. For whatever reason, they sometimes stick in my throat, causing me to choke and/or vomit. It's not pleasant to feel I'm rolling the dice everything I swallow a vitamin. These vitamin C tablets, however, don't have the customary rough coating, but are smooth—and slide right down.

As I said, this can hardly be a review of the product at this point—why do companies ask for reviews from people who can't possibly have enough experience to say more than, "Yep, it arrived in good time and the packaging was intact"? But I asked for non-Chinese vitamin C, and I'm grateful to have found some.

So I'm passing along the information the best way I know.

Here's a PBS story with information on how Neanderthal (and Denisovan) genes live on in modern humans. I'm taking it personally; after all, 23andMe tells me that I have more Neanderthal genes than 91% of their customers: Out of the 7,462 variants we tested, we found 279 variants in your DNA that trace back to the Neanderthals. Granted, my Neanderthal ancestry adds up to less than 2% of my DNA, but it's still more than most people have.

So if you think some of my ideas are old-fashioned, even Stone Age, at least I come by them honestly.

The bad news:

In 2020, research by Zeberg and Paabo found that a major genetic risk factor for severe COVID-19 is inherited from Neanderthals. “We compared it to the Neanderthal genome and it was a perfect match,” Zeberg said. “I kind of fell off my chair.”

The good news:

The next year, they found a set of DNA variants along a single chromosome inherited from Neanderthals had the opposite effect: protecting people from severe COVID.

The science behind the news (links in the quotes) is more than I want to think about, and I have no idea how the protective vs. risk factor genes work out in my case. After all, I may have more Neanderthal genes than most, but that's still only a small fraction, and I don't even know if the variants involved are among those tested by 23andMe. So I'll just go back to making my Covid decisions based on other factors.

And smiling when someone suggests my views are out-of-date.

I've sung before the praises of avoiding anesthesia when possible. Here's an Epoch Times article that confirms my instincts: Anesthesia: The Lesser-Known Side Effect That Could Be Mind Altering. I fear it may be behind a pay wall; if you want to see it and can't, send me an e-mail address and I can give you a "friend referral" that should let you in—at the cost, of course, of letting the Epoch Times know your address. Here are some glimpses at the long article:

If you’re over 65, there’s a significant risk you will wake up from surgery as a slightly different person. Studies indicate at least a quarter and possibly up to half of this population suffer from postoperative delirium—a serious medical condition that causes sudden changes in thinking and behavior.

Delirium is the most common complication of surgery. Until recently, it wasn’t taken very seriously. But researchers believe it can often be avoided—and warrants more study—given its link to long-term and permanent neuropsychotic problems.

A JAMA review noted that up to 65 percent of patients who are 65 and older experience delirium after noncardiac surgery and 10 percent develop long-term cognitive decline. Delirium can lead to longer hospitalization, more days with mechanical ventilation, and functional decline. Even after discharge, functional and psychological health can worsen with increased risks of progressive cognitive decline, dementia, and death.

My grandfather, retired engineer and former college professor with a sharp mind, never recovered, mentally, from a relatively simple operation when he was around my age. I've always blamed the anesthesia, and I may not be wrong.

It's good that the medical establishment is finally taking the problem seriously. Too many doctors expect mental decline in their elderly patients. Yet, in addition to researching ways to minimize the need for general anesthesia, there are already some easy and inexpensive techniques for ameliorating the situation.

More experts and surgeons are also recognizing the importance of post-surgical cognitive rehabilitation. Just as patients who are having orthopedic and other surgeries are guided to get up and move shortly after surgery, there’s evidence that doing crossword puzzles and other cognitive-based activities can help prevent delirium.

Sleep and a support system appear to be two vital ways to prevent delirium. Hospital staff routinely wake sleeping patients for medication, and the various beeps of hospital equipment can disrupt sleep. For those who are hospitalized after surgery, minimizing sleep disruptions is key, according to the Anesthesia & Analgesia article.

"This is particularly important for the older patient for whom the restorative properties of natural sleep are another key part of their recovery. Importantly, family engagement and social support should be implemented early in the preoperative period," the article states.

When we lived in Rochester, New York, one of our neighbors grew red and black currant bushes in her backyard, and shared them with us. Sadly, she moved away soon after we become acquainted, and the bushes were removed. At the time, I thought the new residents just didn't want to bother with them, but maybe they knew something I didn't:

The plants were illegal. Here's the story. (17 minutes at normal speed)

In brief: Plants of the genus Ribes, which also includes gooseberries, are susceptible to a fungus that also produces white pine blister rust, which in the early 1900's was devastating our white pine trees.

Apparently the lumber industry had a more vigorous lobby than the gooseberry family, and our federal government both outlawed the Ribes family and began a massive program of eradication. If it had been the 21st century, gooseberry fans would have been demonetized on YouTube and banned from Twitter.

The federal regulations against Ribes were lifted in 1966, but many states still prohibit or restrict it. My neighbor's yard didn't become a legal site until 2003, and many places in New York still aren't. Here's an interesting list of state regulations. My favorite may be Pennsylvania: "In 1933, Pennsylvania passed a law that limited growing gooseberries and currants in certain areas; however, the law is not enforced. Therefore, all Ribes can be grown in the state."

(It must be pointed out, however, that laws that are traditionally not enforced can still be a threat. if your name is Donald Trump, growing currants in Pennsylvania might still land you in court faster than you can eat one.)

Back in the early 1900's, national governments apparently felt they were faced with a stark choice: save the pine trees, or save the currants and gooseberries. The United States chose lumber; Europe chose food. Both are important, of course, but in hindsight it seems clear that letting nature take its course might have been best. When governments take to using hatchets when flyswatters will do, bad things happen. In subsequent years, better approaches to the white pine blister rust problem have been developed. I suspect these developments would have come sooner if we hadn't decided to commit plant genocide instead.

Because of their great nutritional benefits, Ribes, especially black currants, are making a slow comeback. But I've never seen them in our local grocery store. For that, so far I still need to make a trip to Europe, where currants and gooseberries are easily found.

You might enjoy the post I wrote 13 years ago about my visit to a farm near Basel, Switzerland, where I was allowed to taste freely of gooseberries, three colors of currants, and other marvelous fruits that are difficult to procure here.

UPDATE 1: I have it on good authority that there's at least one farm in New Jersey where I can pick gooseberries and currants if I'm passing through at the right time. It would be interesting to know if "currants" listed on their website also includes the black variety, which New Jersey still heavily restricts—that is, if the Wikipedia article is correct, which is a risky assumption, though less so with currants than with current events).

UPDATE 2: Do not be confused by what are called Zante currants, which look like mini-raisins and are made from small grapes. You can find Ribes black currant products on amazon.com, but a search is more likely to misdirect you, if that's what you're looking for.

UPDATE 3: In the United Kingdom, Australia, and no doubt some other parts of the world, purple Skittles candies are black current flavored. In the United States, the flavor is grape. Not content with trying to eradicate the plant itself, we seem intent on eradicating America's taste for the fruit.

Permalink | Read 1859 times | Comments (2)

Category Health: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Politics: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Travels: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Food: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Conservationist Living: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]