I thought I'd already published my New Year's Eve post, but this heartbreaking news from Quebec demands publicity. For those who don't want to watch the 11-minute video, I've put a short summary afterwards.

Quebec has been iron-fisted from the beginning in its reaction to COVID-19, with tight lockdowns, cancellations, closures, severe restrictions on gatherings in private homes, travel bans, strong vaccine-passport requirements, and even a harsh, five-month curfew.

After much suffering on the part of the Quebec citizenry, the curfew was lifted and the choke-hold on the province's economy and family life began to ease, just a little. Enough for people and businesses to start making plans again.

Until yesterday.

That's when the provincial government announced new extrememe measures in the light of Omicron, the newest COVID variant. These include

- reinstated curfew

- take-out only for restaurants

- no private gatherings in your own home

- in-person school shut down at least until mid-January

And when do these measures take effect? At 5 p.m. today.

Today. New Year's Eve.

Now, I'm not one to go crazy on New Year's Eve. This image I found on Facebook sums it up pretty well for us these days.

But I realize that for many people the New Year's Eve festivities are important. They make plans, they travel, they spend lots of money on clothes and event tickets and parties and food and special restaurant meals. Restaurants, event venues, musicians, caterers and loads of other businesses count on this time to keep them financially afloat.

The decree comes out with one day's notice, and is clearly calculated to pull the rug right out from all New Year's Eve festivities. Plans are already made, tickets purchased, food bought, extra help hired ... then nothing. And all in fear of a COVID variant that has been producing high numbers but is almost always a mild illness with very low hospitalization and death rates.

This is not just tyrannical. It is sadistic.

I wouldn't go so far as to call it Fascist. But it is certainly Faucist.*

We cannot continue to ignore the economic, social, and mental health consequences of these extreme measures.

(Sorry this post is so depressing. My first post of the new year will be more delightful and uplifting.)

*Porter gets credit for this term, but I've latched onto it enthusiastically.

Those who are smart and protecting themselves need to continue doing their best to protect themselves and their loved ones.

I found this in a comment on a friend's Facebook post. One advantage of information overload is that such comments quickly become "anonymized information" in my brain, protecting the innocent and the guilty alike.

What struck me about this statement, with which I heartily agree, is what it tells me about how much we are alike. We all want to protect ourselves and our loved ones, and most of us have opinions as to how best to do that.

It is in the means, not the ends, that we disagree.

Some people move to rural areas and learn to farm. Some organize and join unions. Some purchase and learn to use guns. Others choose to homeschool, or to take political action, or to stockpile food and other essentials. Some work hard to strengthen family and community ties, or to attend to their own physical fitness, or to build up a strong financial base. And some people get vaccinated against COVID-19. Many choose more than one of these paths.

The writer of the Facebook comment was specifically speaking of COVID-19 vaccination, which I certainly consider to be a valid way of choosing to protect oneself and one's family. Unfortunately, the context of the above quotation wasn't as reasonable.

I know this is callous, but those who are smart and protecting themselves need to continue doing their best to protect themselves and their loved ones. What happens to those who do not care, is no longer taking up my headspace.

Just as the excerpt epitomizes what we have in common, the context shows what is dividing us. Because by "those who do not care," the writer appears to mean those who choose not to follow his own particular choices. Possibly, he's expressing his willingness to leave them alone to make their own decisions. But the callousness, which he admits, contains the implication that he considers doing them harm to be a valid part of protecting himself.

That is very dangerous ground indeed. We can do better.

Permalink | Read 1056 times | Comments (0)

Category Hurricanes and Such: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Health: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Politics: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Random Musings: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

"Find Your ZZZs: How to Get the Best Sleep Every Night"

It was a two-page article in our local city newspaper—and very large print at that. So I certainly couldn't have expected anything profound. I'm only calling it out because I was struck by how inapplicable it was to me. The advice given must work for many people, because I've heard it in just about every article I've read about sleep. But one size simply doesn't fit all, and I wish that were more universally acknowledged. Here's some of the advice given:

- Set your bedtime so that you wake up at the end of a 90-minute sleep cycle Not applicable, since I'm one of the blessed people who almost never uses an alarm clock. I wake up when I wake up, and figure there's no need to worry about sleep cycles.

- 30 minutes to an hour before bedtime, turn off bright lights and put devices away "Avoiding screen time at least 30 minutes before bed is critical to your quality of sleep." That's a very common recommendation, but for me just a few minutes of reading or doing puzzles in bed is the best trick I've found for putting me right to sleep, and it doesn't matter a bit whether they're print or electronic.

- Decrease the amount of disruptive light in the room with blackout curtains or a sleep mask. This might actually be useful. Light doesn't keep me from falling asleep, but our neighbor's bright, motion-activated light does wake me up and make me wonder which of our wild animals is dancing on the lawn.

- Keep your room a cool temperature (experts suggest between 60 and 67 degrees) Right. Maybe that works for a northerner, but running the A/C that much is not in our budget. Besides, at that temperature, I'd be wearing my winter pajamas and huddling under the blankets.

- Invest in your sleep with a supportive bed and comfortable bedding You mean the mattress and box springs we got second-hand from my in-laws almost 20 years ago should be replaced? At least the author had the grace to admit that "upfront costs of a new bed may be intimidating"—as we re-discover every time we think we might do just that.

- Don't use the snooze button Not a problem, since I'm not using an alarm clock.

- Expose yourself to sunlight when you get up Hmm. I think not. Since I'm usually up a couple of hours before sunrise, that's not going to happen; it's especially hard during Daylight Saving Time.

I'm not complaining; I'm sure the article was helpful for some folks. But I do find that more and more these days people are over-generalizing when it comes to what other people are like. I guess we just need to be more aware of what truly works for us and not worry about what other people think.

Actually, I do have one complaint, I suppose: With all that advice about going to bed and waking up, they did not address the only trouble I do have with sleeping: getting back to sleep after awakening in the middle of the night! Praying is the best help with that—but only memorized prayers; if I have to think to any extent it only speeds the squirrel-wheel in my brain.

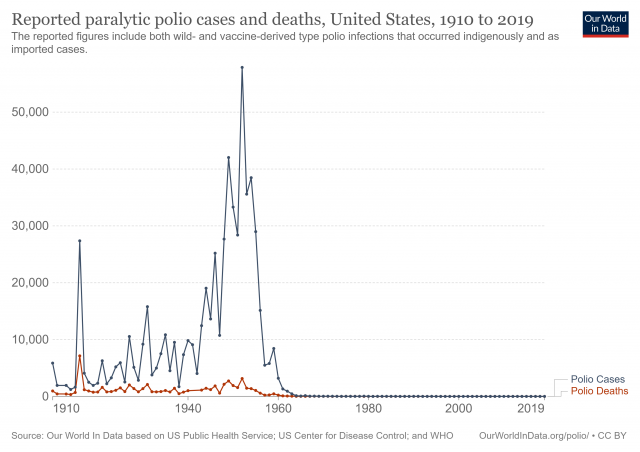

In research inspired by my previous post, Measles Wipes Out the Immune System?, I discovered this interesting article on another disease, polio. Most of all I was struck by this explanation of the huge spike in the disease that occurred in the middle of the 20th century:

Up to the 19th century, populations experienced only relatively small [polio] outbreaks. This changed around the beginning of the 20th century. Major epidemics occurred in Norway and Sweden around 1905 and later also in the United States. Why did we see such large outbreaks of polio only in the 20th century?

The answer ... lies with hygiene standards. As polio is transmitted via the fecal-oral route, the lack of flush toilets and the lack of safe drinking water meant that children in the past were usually exposed to the poliovirus before their first birthday already. At such a young age, children still benefit from a passive immunity that is passed on from their mothers in the form of antibodies. ... Thereby, virtually all children would contract the poliovirus at a very young age. While protected from developing the disease thanks to the maternal antibodies, their bodies would produce their own memory cells in response to the virus and that ensured long-term immunity against polio. The latter is important as the mother’s cells have a half-life of only 30 days (starting from the last day of breastfeeding). Once the maternal antibodies decrease in number, children lose their passive immunity. As hygiene standards improved, the age at which children were first exposed to the poliovirus increased and this meant that the maternal antibodies were no longer present to protect children from polio.

That improved sanitation was a driving factor in polio outbreaks is also illustrated by the fact that the age at which polio was contracted increased over time. During five US epidemics in the time period 1907-1912, most reported cases occurred in one- to five-year-olds, whereas during the 1950s the average age of contraction was 6 years with "a substantial proportion of cases occurring among teenagers and young adults." Being exposed to the poliovirus after losing the protection from maternal antibodies meant that they were more likely to get polio.

The dramatic dropoff in cases in the 1950's shows the effectiveness of the newly-developed polio vaccine.

I find the progression fascinating. The world achieves a steady-state coexistence with the disease, in which mothers' acquired immunity protects their children while the children develop immunity of their own. Then, thanks in large part to laudable and desirable public health advances, the disease gets the upper hand and skyrockets. (The article does not mention this, but I'm certain that the decline of breastfeeding during this time period also contributed significantly to the disruption of the natural protection against polio.) Finally, vaccine development and widespread implementation nearly wipes out the disease.

The emphasis on "nearly" is important. There is hope that, like smallpox, polio will completely eradicated. Smallpox dropped off the list of recommended vaccines when the risk from the vaccine became greater than the risk of the disease. Someday soon I hope the polio vaccine will also be relegated to history. In the meantime, however, we must not become careless nor complacent about the vaccine. We no longer have the natural immunity passed between mothers and children, and nothing short of a catastrophe will return us to those times. We have reason to feel quite safe here in the United States, but consider this from the article:

As of 2017 the virus remains in circulation in only three countries in the world—Afghanistan, Pakistan and Nigeria.

Do we want to completely shut our doors to the visitors, immigrants, and refugees who come here from these countries? If not, we'd better continue to make vaccination against polio a priority.

Here's a very strange news story out of the usually-reasonably-trustworthy BBC News: Measles resets the immune system.

"Immune amnesia" [is] a mysterious phenomenon that's been with us for millennia, though it was only discovered in 2012. Essentially, when you're infected with measles, your immune system abruptly forgets every pathogen it's ever encountered before—every cold, every bout of flu, every exposure to bacteria or viruses in the environment, every vaccination. The loss is near-total and permanent. Once the measles infection is over, current evidence suggests that your body has to re-learn what's good and what's bad almost from scratch.

Scientists have known for decades that even after they recover, children who have been infected with measles are significantly more likely to fall ill and die from other causes. In fact, a study from 1995 found that vaccinating against the virus reduces the overall likelihood of death by between 30% and 86% in the years afterwards.

I find this bizarre and completely counter-intuitive. Nearly everyone my age and older has experienced a measles infection, and this phenomenon doesn't make sense given my experience and that of those I know, i.e. that of normal, healthy, well-nourished children who have suffered from measles. I say "suffered," but will make the point that in my case it was hardly suffering. Measles was just one of several infections that got you out of school for a week or two and earned you extra parental attention and breakfast in bed.

What we were not is sickly. We were nothing if not robust. Polio had been licked by the new vaccine, and everything else we endured for a few days and then were back in the business of causing general havoc in the fresh air and sunshine.

Probably the greatest threat to our health was secondhand smoke: nearly everyone smoked nearly everywhere. That and the strontium-90 cloud that passed through our village in my early childhood....

If our immune responses had been wiped out by getting measles, I would think we'd have seen an increase in illnesses post- versus pre-measles. Does anyone of my generation remember that? I don't. If our immune systems forgot every other vaccine and pathogen they had previously encountered, they seem to have re-learned their responses quite quickly.

Certainly the subsequent generations of children do not seem to me to be noticeably healthier than my own, if you consider the "normal, healthy, well-nourished" cohort I mentioned above. New vaccines have kept them free of most of the early childhood diseases, but instead of dealing with a few days of illness they're at increased risk of lifelong asthma, any number of food allergies, and even autism. Correlation does not imply causation—but let's just say that I don't feel I got a bum deal growing up in the 1950's. Except for the secondhand smoke part.

I'd like to hear more about this new discovery of the effects of measles. Crazier things are true. It just seems weird to me.

As I wrote before, we recently made our first airplane voyage since before the start of the pandemic. I was surprised at how rusty we were in what used to be accustomed procedure!

Overall, I was impressed, as I usually am, by Southwest Airlines. We flew during their recent—and never satisfactorily explained—outage, and our outbound flights were cancelled. However, we were automatically rebooked, within minutes of that notification, on a flight that left later the same day and arrived at our destination earlier, a much better situation for us. Between that and having automatic TSA Precheck, our airport experiences were problem-free. And I'm very happy about the improved cleaning and air filtration procedures, since in my experience an airplane is nearly as dangerous as an elementary school when it comes to challenges to the immune system. That part of the flight felt good.

Not that we had all that much chance to experience the new, fresher air, as masks were required to be worn at all times, even between bites and sips while eating and drinking. Fortunately, the between bites part was not aggressively enforced, but neither was there all that much opportunity for eating and drinking.

I can handle a mask, when necessary, for short shopping trips, and can make it through a choir rehearsal or a church service, albeit with difficulty. If I had to wear a mask for my job, I'd be applying for a medical exemption. I have no disability other than age, but that was good enough to get me priority for the vaccine, so maybe it would work. Fortunately, employment is not an issue.

Wearing a mask for the trip was hard. Ours was a relatively short flight, but that was three hours, and of course you have to add in the airport time on either end. Still, we managed all right, as far as I could tell.

The scary part was on the flight home, when I had the elbow room to use the sensor on my phone to check my blood oxygen. I know I'm good at sleeping on airplanes, but I couldn't stay awake to read a very interesting novel, and that concerned me. The sensor on my phone is hardly as accurate as a medical pulse oximeter, but there has to be something wrong about the fact that it consistently reads between 95% and 100% at home (usually on the high side of that), and my readings on the plane were between 84% and 90%! Pulling the mask away from my face for several breaths got it up to between 93% and 97%. But for how long had I been in the danger zone? Was the problem due to wearing the mask, or the altitude, or a combination? All I know is that when I got back home the numbers were up to 97%-100% again.

I'm trying not to think too much about the fact that our overseas family, including small children, had to endure two very long transatlantic flights for their Christmas visit here, and were forced to wear medical masks because their own cloth masks—similar to mine—were deemed to allow too much air exchange.

This won't stop me from flying again, even overseas when that is allowed. Family is too important. But at my age I need all the brain cells I can keep. Who doesn't, at any age? (That's one reason I avoid anesthesia whenever possible.) I'm more and more convinced that the harmful effects of our pandemic regulations are only just beginning to be felt.

My constant prayer since the start of the development of the COVID-19 vaccines has been that the knowledge gained would lead to an effective vaccine against malaria.

When I last checked the Johns Hopkins site, the total estimate of COVID-19 cases since we started keeping track have been a little less than 237 million. (Just how accurate that guess is, is another issue.)

In that time period, there have been approximately 382 million cases of malaria, a debilitating disease that cripples economies, and preferentially kills young children.

But there is good news. While there is still much room for new vaccine-development techniques to improve the situation, there is now a vaccine for malaria. It was developed by GlaxoSmithKline* and proven effective six years ago. Finally, after futher testing, has been given the green light for mass vaccinations in sub-Saharan Africa.

"Effective," in this case, is only 40%—I said there was room for improvement—and requires a series of four shots, given at five, six, seven, and 18 months of age. In a part of the world where health care is often less than stellar, I imagine this will be a challenge to implement. But malaria is a much trickier disease than, say, COVID ("comparing them is like comparing a person and a cabbage") and this is a huge milestone.

It causes all, both small and great, both rich and poor, both free and slave, to be marked on the right hand or the forehead, so that no one can buy or sell unless he has the mark. — Revelation 13:16-17

College is a time for wide-ranging, speculative discussions, and among my fellow students in the early 1970's this Bible verse was a popular topic. We were hard-pressed to imagine a world in which people would consent to having marks imposed on their bodies: tattoos were so rare that most of us had never seen one, and the now-common practice of implanting informative microchips in pets was 15 years in the future. The microchip itself had barely made any impression on our lives—my choice when doing my physics homework was between long, laborious hand calculations and a long trek through the snow to a small room where half a dozen chunky, very basic calculators had been made available to students.

Even more puzzling was how having or not having this "mark of the beast" could be the gateway to commerce. The marketplace still ran on cash and checks.

How much can change in 50 years.

Suddenly, in Canada, in Australia, in Switzerland, and in parts of the United States, the marketplace and much more are now gated by vaccination status. Society has been divided as by a sharp sword between the haves and the have-nots; the clean and the unclean; the ones who are free to travel, attend school, eat at restaurants, and even hold their jobs, and those who are not.

I am not saying that the COVID-19 vaccine is the Mark of the Beast. It seems clear that the Mark will involve some form of blasphemy and idolatrous worship, and this does not—although, frankly, the efforts to invalidate religious exemptions to vaccine mandates have me wondering a bit about that.

However, it is now crystal clear is that what seemed impossibly fanciful back in my college days is not only possible, but can sweep over even a free and democratic country with little effective opposition. Whatever that Mark may be, we have opened the door.

Our doctor's office has yet another set of forms for us to fill out, and this one just has me wanting to throw up my hands and scream, "NONE OF YOUR BUSINESS!" Plus, some of the questions make no sense, in some cases giving far more options than reasonable, and in some cases too few.

For "Ethnic Background" I am given these options:

- Ashkenazi

- No

- Other

- Unknown

I understand that there are certain diseases that are more prevalent among Ashkenazi Jews, so maybe that's an important question. But there are also diseases that are especially prevalent among other populations, e.g. the Amish, and there's no opportunity to indicate that, other than the non-informative "Other." And just who are the No people—an obscure tribe of Papua New Guinea, perhaps? And is my own diverse ancestry, which took up some dozen slots on the 2020 census form, of no medical interest at all?

One ethnicity gets its very own question:

- Hispanic or Latino/a

- Not Hispanic or Latino/a

- Unknown or Not Given

I find that a curious question for a doctor to ask. Just how many diseases divide themselves by this criterion? If my lungs are congested, how much does it matter whether my ancestors came from Spain versus France? "Not Given" is beginning to look like the best answer for most of these questions.

There's a good deal more choice when it comes to Sexual Orientation:

- Bisexual

- Choose not to disclose

- Don't know

- Lesbian or Gay

- Something else

- Straight (not lesbian or gay)

- (You can hold the CTRL key while clicking to select multiple options)

Frankly, unless I'm indicating problems of a sexual nature, I don't think even my doctor needs to know this information, though she's welcome to guess based on the fact that I'll admit to being female and having a husband. "Something else" sounds attractively bear-poking, however.

But even Sexual Orientation has nothing on Religion!

- African Methodist Episcopal

- Agnostic

- Amish

- Anglican

- Assemblies of God

- Atheist/Humanist

- Baptist

- Buddhist

- Catholic

- Christian

- Christian Scientist

- Church of Christ

- Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints

- Decline to Answer

- Disciples of Christ

- Episcopalian

- Greek Orthodox

- Haitian Vodou

- Hindu

- Indian Orthodox

- Islam

- Jain

- Jehovah's Witness

- Jewish

- Lutheran

- Mennonite

- Messianic Judiasm [that's how they spelled it]

- Methodist

- Multi-Faith

- Nazarene

- Non-Denominational

- None

- Orthodox

- Other

- Pentecostal

- Presbyterian

- Protestant

- Quaker

- Rastafarian

- Russian Orthodox

- Scientologist

- Seventh Day Adventist

- Shinto

- Sikh

- Taoist

- Unitarian Universalist

- United Church of Christ

- Unknown

- Wiccan

- Zoroastrian

There are so many things wrong with this list I won't even try to ennumerate them, other than to mention that my Seventh-Day Baptist ancestors would be feeling left out. And to note that it's just plain weird to have so many choices yet list "Islam" as one-size-fits-all. For myself, being unable to choose among Anglican, Christian, Episcopalian, Multi-Faith, Non-Denominational, Protestant, and Other—and not having the ctrl/click option for this one—I might have to go with that fascinating new religion, Decline to Answer.

But really, of what possible importance could the answer to this question be for normal medical care, other than the above-mentioned correlation between being Amish and certain diseases? Even that is an ethnic difference, not a religious one. Do Wiccans require different cancer treatments from Zoroastrians? True, Jehovah's Witnesses don't want blood transfusions, so that's important to know, but I think it would be safer and more efficient to ask that question directly, rather than make the assumption. I suspect not all JW's reject them totally, and for all I know, some other religion frowns on them as well.

Maybe these questions are required by Medicare. I have had more patience with my medical caregivers (though less with the government) ever since I learned that the very annoying questions they started asking at every visit were government-imposed: Have you fallen at all in the last year? "I have grandchildren. Falls are the natural consequence of fun." Have you been depressed during the last year? "I'm here for a physical, not a mental."

It's a good thing we like our doctors. The bureaucracy is rapidly eroding my confidence in the system.

Finally, someone—someone whose work I respect—has said what I have been saying since the beginning of the pandemic lockdowns. I'm tired of being laughed at, and much worse, when I point out that it is inconsistent to excoriate people who resist some of the anti-pandemic measures, while at the same time themselves not thinking twice about driving a car. Both are actions that can endanger others, but most of us have decided to give automobile dangers a pass. We think so little about them that we tolerate, even joke about, impaired driving, speeding, road rage, poorly-maintained cars, and driving without a license or insurance coverage. Cracking down in these areas would no doubt make a huge difference in automobile injuries and fatalities. But even then there would be dangers from weather, from carelessness, and from that wasp that flew in the window and is crawling into your ear. (The last really happened to a friend of ours, who managed to get off the road safely—I'm not sure I could have.)

You want to protect yourself and others? If you can't walk to where you are going, stay home.

But of course we don't do that. The consequences would be too great.

I want people to understand that the various measures we are taking against this pandemic also have great consequences, ones that are not as immediately obvious as ending up in a COVID hospital ward.

George Friedman says it well in his article (from which I took my own post title), COVID and Cars. Unfortunately, it is behind a pay wall, but I've extracted a few quotes.

Every year in the United States, about 40,000 people die in car accidents. Some 1.35 million die in car accidents globally. In fact, they are the eighth-largest cause of death in the world. In the United States, about 3 million people are injured in automobile-related accidents.

These numbers exist despite all the efforts made to make cars safer. The reason cars aren’t banned is because the economic and social consequences of doing so would be devastating. The supply of food and other essentials requires trucking. Maintaining friends and seeing family require cars. In the United States, our ability to use land efficiently depends on cars to sustain a dispersed population. Yet this dependency carries a risk. In the back of your mind, you are aware as the ignition is turned on that you may die. You dismiss this possibility, of course, and proceed with your life.

What has happened is that a known risk of death and injury has been measured against the necessities of life, and a calculated risk has shown that tolerating the chance of death and enjoying the benefits of the car is preferable to seeking to eliminate car deaths by eliminating the car. The principle that death must be fought by all means is not practiced in the case of car deaths because a more subtle calculation takes place.

It’s a reminder that in most actions of human life there is a possibility of death or injury, but a life without those things would be impoverished. You can live without many things for a short and predictable period. Living without them indefinitely creates pressures on individuals and society. The trade-off between death and life is the human condition.

The idea that we can go on indefinitely with each new chapter forcing us to shelter in place is a superficial view of what will happen. As with automobiles, where we risk death on every ride and where many find it, the risk of COVID-19 will be integrated into our thinking, and we will make choices.

Part 1 of the visit of our Swiss family is here, part 2 here.

At last, Christmas drew near, and we focussed our activities nearer home. Christmas Eve saw us in church, of course, with some of our guests pressed into service in our hand chime choir. Hand chimes are not nearly as beautiful as handbells, but they are what we had. We didn't even have a handbell choir until it emerged as a desperation move to give our choir a way to make music when rehearsing and singing were forbidden. In this we were oppressed, not by the state, but by our very own bishop, whose rules were far more draconian than the governments'. I had so looked forward to being able to share with our family the absolute beauty of our high church worship, especially on such a special day, but it was not allowed to be. Nonetheless, we were grateful to be permitted in-person services at all. We were there; God was there. And some of us went back later for the midnight mass.

cropped.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

Credit for the above three photos Anke Cirillo of Three Point Photography

And then it was Christmas! Happiness is a house full of family.

After Christmas we boldly got together with our long-time friend and former choir director for one of our spontaneous music-making sessions. It's impossible to describe what a glorious outpouring of joy there is in these events. I do have a few recordings I treasure, but out of respect for the true musicians who don't always appreciate having their impromptu experimentations broadcast to the world, I'll leave it to your imagination. We had singing, piano, harmonica, viola, recorder, hand chimes, and all manner of percussion. If I could do this every night I know my mental state would take a drastic turn for the better. And the interaction between me on the tambourine and our granddaughter on the maracas was pretty good physical exercise, too.

We visited several playgrounds and natural parks, including taking the Black Point Wildlife Drive on the east coast. It's a favorite of ours, and a lovely place to see birds. On this trip, however, the more exciting views were of another sort:

And what's a trip to that part of the state without a stop at the Dixie Crossroads restaurant?

We continued to enjoy our final days of this visit, trying not to think too much about the upcoming long trip to Miami and the even longer trip across the Atlantic. And the 10-day quarantine awaiting them back in Switzerland. But they survived all that without catching COVID-19, and so did we. We are so grateful to Florida for welcoming our overseas family, to Switzerland for letting them come (and return), and to all whose efforts made this visit possible. I hadn't fully realized the toll these pandemic restrictions had taken on our mental health until we were reminded of what we were missing. I believe this visit came just in time, and I'm so glad we made the joyful choice.

This December visit seems more than six months distant, given that January and February brought us vaccines and the beginning of more freedom, at least in Florida. It would be April before the Northeast opened up enough for another healing family visit ... and that's a story for another post.

Permalink | Read 3971 times | Comments (0)

Category Hurricanes and Such: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Health: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Politics: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Children & Family Issues: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Everyday Life: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

Being a Floridian, and one who has enjoyed several cruises, I was naturally intrigued by the following Viva Frei episode in which attorneys David Freiheit and Robert Barnes discuss Florida's lawsuit against the CDC's shutdown of the cruise industry. The video is just under 14 minutes long.

As I said, the story was of mild interest to me from the beginning. It was already on my "blog about this, maybe" list. However, it turns out to have a personal angle that makes it even more compelling. Unfortunately, I can't talk about it for privacy reasons, but it serves as a clear though pleasant reminder that no matter how nameless and faceless the machinations of government and business seem, there are real, everyday people behind them all. We forget that to our peril.

Last Sunday, Viva & Barnes revisited the story, reporting that the judge, instead of ruling on the case, sent both parties to mediation. (The relevant part of the video is 26:18 - 28:29.)

Here is another example of what a difference "spin" makes in news reporting. Barnes clearly sees the mediation order as an indication that the judge would rule in favor of Florida if he had to, and as a way for the him to let the CDC save face while keeping himself from being accused of "killing granny." However, most news articles I read have reported it as a setback for Governor DeSantis, and pointedly place the blame for cruise ships fleeing Florida, not on the CDC's restrictions, but on both DeSantis and the Florida Legislature for forbidding discrimination against people who have not been vaccinated.

I certainly hope that Barnes is right, and more accurate in his analysis of the judge's inclinations than he was of the judge's gender—though these days I'll admit the latter is a trickier call than it ought to be.

Part 1 is here. Now for more of our adventures during our December attempt at choosing joy and life amidst a pandemic-inspired focus on fear and death.

The eight of us did most of our venturing-outside-the-home together (being blessed with a car that seats that exact number), but occasionally we split up, as when two of us spent a day at EPCOT and the rest of us sought our entertainment at a classic American mini-golf course. Both groups had great fun. Credit goes to Disney for keeping their parks open and at the same time uncrowded so that the experience felt safe as well as fun. Remember that back then we knew much less about outdoor transmission (or lack thereof) of the virus, and people were nearly as scared outdoors as inside. The golf course was similarly comfortable.

Left: Congo River Golf; Right: EPCOT at night. Click to enlarge.

We also separated to give Janet and Stephan a chance to celebrate their anniversary on their own. They chose a hotel on Daytona Beach, and we joined them the next day for the chance to swim in the Atlantic Ocean on the first day of winter. Porter and I declined the swim, as it was 66 degrees, cloudy, and windy. That didn't stop the hardy Swiss, however! I didn't realize until we arrived that they had chosen a hotel on the same section of beach where I spent so many happy hours as a child—a five-minute walk from my grandparents' house. The coquina-built bandshell is much the same, and so is the ocean, but almost nothing else.

Closer to home, we visited the Orange County History Center, which thoughtfully made it possible to see the good stuff while avoiding the decidedly-child-inappropriate special exhibit of history's darker side. We picked out and decorated our Christmas tree, made cookies, and generally prepared for the holiday, which is not surprisingly much more fun with children around. We visited playgrounds, worked on various projects at home, swam some more, and sang and played music together.

Only twice in our entire month together did I feel the least bit uncomfortable with regard to COVID-19. The worst was at our local pizza party arcade, since we arrived at a time when a large party of people without masks crowded the place. Fortunately it was easy to return later.

The second time was at Sea World. I mean no particular criticism of the park, which clearly took precautions very seriously: taking temperatures, requiring masks, keeping even the outdoor stadiums at low, well-distanced capacity. But overall the park was more crowded than allowed for comfortable distancing, unlike our experience at EPCOT. However, this was on December 23, one of the busiest days of the year, one we'd normally have avoided like the plague. (Perhaps that analogy isn't the best one to use at this time.) The experience was overall delightful and certainly much more pleasant than it would have been in a normal year.

More to come.

Permalink | Read 1538 times | Comments (1)

Category Hurricanes and Such: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Health: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Politics: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Children & Family Issues: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Everyday Life: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

According to this article,

During an interview on CNN's "State of the Union," [CDC director Rochelle] Walensky was asked about vaccinated Americans who have contracted the virus—and whether anyone has died from an infection, despite being inoculated. Walensky said the CDC is aware of 223 so-called "break-through" infections in vaccinated Americans, but clarified that many of those individuals died due to other causes. "Not all of those 223 cases who had COVID actually died of COVID," she said. "They may have had mild disease but died, for example, of a heart attack."

This makes perfect sense to me. From the beginning of this pandemic, I have been frustrated by seeing a clear tendency to report all deaths in anyway associated with COVID-19 as caused by the virus. Witness the testimony of a friend of ours, a nurse, who (in another state) was ordered to count as new, active COVID-19 cases anyone who tested positive for the COVID-19 antibodies—which meant that many cases were counted multiple times. And that of an Emergency Medical Technician I know who only partially joked, "If someone with COVID-19 is run over by a truck, his death is counted as a COVID-19 death." Then there's the death I know about that was put down as due to COVID-19 but should have been "nursing home neglect." Of course these are isolated examples, but good luck trying to convince me that they aren't representative of widespread mis-information.

What it comes down to is this: What are you trying to prove?

When the powers-that-be were trying to justify elaborate and invasive regulations in reaction to the pandemic, it was to their advantage that the numbers be as large as possible. But when the object is to reassure the public of the safety and effectiveness of the vaccine, the advantage lies in giving the virus no more blame than is absolutely undeniable.

I happen to believe that the CDC is closer to the truth in the case of the vaccine, but that's not the point. What's important is that with every report, every news story, every rumor,

Always, always, always ask, Cui bono?

Who benefits? What are they trying to prove? Follow the money.

This is the post I started to write five months ago, but postponed to make sure everyone involved got through their quarantines and other impedimenta successfully.

I like to think that we've been more careful than most during this pandemic, though more due to the concern of our children (who apparently think we are "old") than our own. But when you're retired, and introverted, and not easily bored, staying home is a pretty easy option. We wore masks before our county made them mandatory, shopped only for what we deemed necessities, and used the stores' "senior hours" when we could. I'm also the only person I know who consistently washed (or quarantined) whatever we brought home.

But all that isolation, particularly the lack of physical touch, is hard even on introverts.

Hardest of all was cancelling our big family reunion scheduled for April 2020—coinciding with what was supposed to be the first visit home in six years of our Swiss family. Following close behind were missing our nephew's wedding, our normal summertime visit to the Northeast, and our long tradition of a huge family-and-friends Thanksgiving week of feasting and fun, all of which would have involved being with most of our American-based family. Plus the breaking my fourteen-year streak of travelling overseas to visit our expat daughter and her family (one year to Japan, thirteen to Switzerland).`

I know that doesn't begin to compare with the hardship endured by those who were forceably separated from loved ones who were sick or dying. But when the "temporary measures to keep our hospitals from being overwhelmed" turned into unending months of restrictions—with our hospitals so far from overcrowded as to be financially strapped due to underutilization—even normally compliant people like us began to chafe.

Even as we relaxed and let go of much of our fear, we remained vigilant in our precautions, for a very good reason: a light, not at the end of the tunnel, but a much-needed illumination in the middle of the tunnel. We needed to stay healthy, because...

The reunion remained off the table, due to onerous quarantine requirements imposed by the states the rest of our family live in. But thanks to much work on their part, and a state government more enlightened than most, our European family was able to visit us in December. Rarely have I been so happy to be living in Florida, which welcomed them with open arms. So of course did we! Mind you, I think the CDC was still recommending we wear masks all the time with visitors and stay six feet apart, but naturally that didn't last six seconds! A year apart from family is far too long, and that goes tenfold for grandchildren. Sometimes you just do what you have to do.

We did the risk/benefit analysis—and made the joyful choice.

Porter had to drive to Miami to pick them up, because so many flights had been cancelled. But he would have driven farther than that to bring them home!

We had been prepared to stay mostly around the house, just enjoying each other's presence. And at first we did a lot of that, since merely being in America was adventure enough for the grandkids. But they were here for a month, and most of the tourist attractions had reopened, albeit at reduced capacity, so we took full advantage.

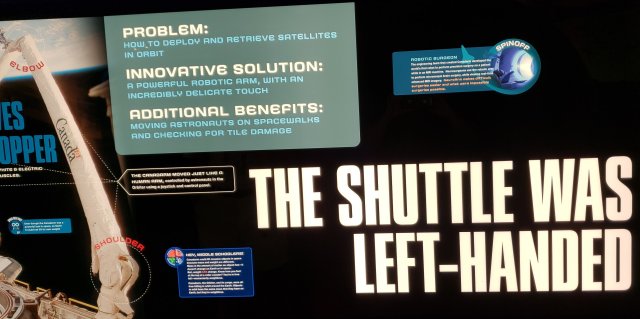

Kennedy Space Center was amazing. We were not the only visitors in the park, but at times it seemed like it. Sadly, some of the attractions were still COVID-closed, but there was certainly plenty to see. The following photo is for the lefties in our family:

One of the trips I enjoyed the most was to Blue Spring State Park, which was visited by more manatees than we've ever seen naturally in one place. The weather was perfect—that is, cold. Cold weather drives the manatees from the ocean and the rivers into the relatively warm water (about 72 degrees) of the springs. The air temperature made most of us keep our masks on even though that was not required except inside the buildings, since we discovered them to be very effective nose-warmers.

Another favorite activity was swimming. (Not with the manatees; that's no longer allowed.) The intent was for most of it to be in our own pool, and indeed it was, but there had been a glitch: We purchased a pool heater, knowing that our pool temperatures in December can dip into the 50's (Fahrenheit). However, the unit that was supposed to have been installed before our guests arrived was delayed again and again. Whether it was actually the fault of the pandemic is anyone's guess, but that's what took the blame. It finally arrived just a few days before they had to return to Switzerland. Until then, the children swam bravely, if not at length, in the cold water, and all of us enjoyed the (somewhat) heated pool at our local recreation center. And then they really appreciated our own heated pool for those last few days.

To be continued....

Permalink | Read 1476 times | Comments (1)

Category Hurricanes and Such: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Health: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Politics: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Children & Family Issues: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Everyday Life: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]