When I was very young, my mother used to make apricot-pineapple conserve. I have the recipe; it's simple, just dried apricots, crushed pineapple, and sugar. The tricky part is that the mixture, while cooking, bubbles and spits and must be stirred constantly. My father made a long, L-shaped wooded paddle so she could stir from beyond the surprisingly-long range of the very hot mixture. When my mother made conserve, it was an event.

Which may be why I've only tried the recipe once or twice. That, coupled with the fact that Porter doesn't care much for apricots and even less for pineapple, so other jams take much higher priority around here.

But I miss it, and am always eager to try it out when I find a jar in the grocery store. But those occasions are rare.

Then I got smart.

There, at our local Publix, was the solution. Well, not the ideal solution, but a great deal easier than making my own. Mixed together, the flavor is just about as I remember it, though the texture is a bit thicker. One of these days I still plan to make it from scratch, even though I lack my mom's amazing paddle. But in the meantime, this provides an awesome gustatory memory.

When we were in Chicago recently, our first meal was at the amazing Russian Tea Time restaurant. It was a special occasion; if we lived in Chicago, the expense would make our visits rare. But if I were there now, I'd make a point of taking in another of their wonderful Afternoon Teas. Whatever we may think of the recent actions of Vladimir Putin, it makes no sense to penalize our Russian neighbors. This is the letter we received from the owners of Russian Tea Time.

Dear RTT patrons and friends,

We are heartbroken by the recent news; our thoughts and prayers are with those who are affected by this inhumane and despicable invasion. We do not support politics of the Russian government. We support human rights, freedom of speech, and fair democratic elections.

Украинцы (Ukrainians), the world is with you, the world is behind you. Stay strong, our hearts are with you!

The past two years have been so very hard on restaurants; they don't need any more grief.

Besides, you never know who it is you're actually affecting. The owners of our favorite place for sushi in Central Florida (now, alas, no longer in business) were Vietnamese, not Japanese.

The owners of Russian Tea Time are Ukrainian.

Permalink | Read 1516 times | Comments (2)

Category Hurricanes and Such: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Politics: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Travels: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Food: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

Sometimes the Babylon Bee gets it just right: Perfectly Good Cookie Dough Ruined by Putting It in the Oven.

Frankly, I'm also a fan of baked cookie dough. But I've said it before and I'll keep saying it: If our food supply is so unsafe that milk and juice must be pasteurized to be safe, if raw eggs and even raw flour are considered dangerous, and if we are continually urged to overcook our meat—then something is tragically wrong with our food supply.

Treating the symptoms must be only a stop-gap measure. We need to fix the problem, rather than condemn ourselves and future generations to inferior food.

My readers from Florida will recognize that even the best citrus juice you can buy in a grocery store is a pale imitation of the Real Thing. Standardization and pasteurization may make for a consistent product that can be safely transported all over the country, but what it does to the taste is almost unconscionable.

I'm here to tell you that the same thing is true of apple juice, and apple cider.

These days, what is sold as apple juice is slightly flavored sugar water. Process it just slightly less and give it the label "cider" and it's drinkable. Several years ago, when new regulations made it nearly impossible to get unpasteurized cider, this became true not only in Florida but for most of the rest of the United States as well. But I spent my childhood in upstate New York, where fresh apple cider was one of the greatest autumn joys. Unpasteurized, unfiltered, the flavor varying with the variety of apples pressed.

No one who has not experienced the difference can understand how much harm pasteurization does to flavor, be it of orange juice, cider, or milk. In the Live Free or Die state the orange juice is as bland as anywhere, but I've been enjoying fresh-from-the-farm milk, as I do in Switzerland.

And recently we made our own cider.

Picking.

Prepping.

Put it into the refrigerator straight from the press and you get an incredibly refreshing drink that explodes with the taste of fresh-picked apples. Let it sit on the counter for a day first and you get a slightly carbonated, slightly fermented drink reminiscent of Swiss apple cider.

I'm certain that letting it ferment longer would eventually give hard cider, then vinegar. But it always disappears before it can get to that point, even if we wanted to. :)

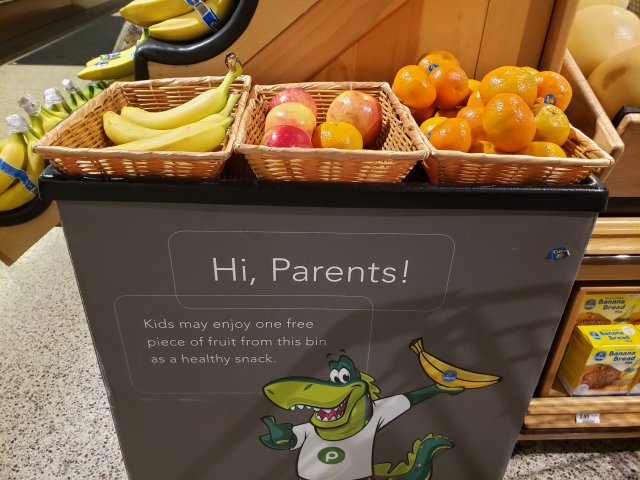

I was pleased to see the following display at our local Publix. It's certainly a healthier alternative to the cookies that are usually offered to children at grocery stores.

Then I thought a bit about it. It may be a healthier treat, but there's one thing missing: it's just a bin of fruit; there is no human interaction.

Years ago, when our kids went to the bakery to receive their much-anticipated free cookies, it was a social event. The interaction with the "cookie lady"—the smiles, the brief exchange of words, the opportunity to practice basic courtesies such as saying "thank you"—was a small but significant part of their social education. Reaching into a bin is impersonal.

Something is gained, but something is lost.

Many years ago our Swiss relatives marvelled at how much of American society is not automated. Switzerland automates where it can—in paying tolls and parking fees, for example—because labor costs are so high there. It is good to have work in Switzerland, because jobs pay well and workers are respected. But of course in consequence there are fewer jobs and they require higher levels of training.

Like it or not, the move toward automation is accelerating in America, spurred on by our response to the pandemic and the consequent labor shortage. This is not necessarily a bad thing, but there's no doubt that whenever we make a purchase online, choose a self-checkout line at the grocery store, take a course online instead of in person, listen to a sermon or watch a service online instead of attending a local church, or watch a movie at home instead of in a theater, we are giving up an opportunity for meaningful interaction with others.

I'm a cast-iron introvert, and my first reaction is, "So what?" The less personal option is usually more efficient, more convenient, and avoids the risk of having to deal with rude sales clerks and cranky classmates. Automation and online opportunities open up a huge world of information, possibilities, and choice.

The danger is that they can close off another world: the messy world of having to control our nastier impulses and deal with the personalities, cultures, viewpoints, and yes, nastier impulses of other people; the beautiful world of personal encounters that force us to see the humanity of those whom we might be tempted to hate if our encounter were in an online political forum instead of a line at Home Depot.

The juice on the right is fabulous Florida orange juice, unhomogenized, unpasteurized, unadulterated in any way. Although it did come from a large grocery store (Costco), it's the best I can get outside of squeezing my own or visiting a grove. It's head-and-shoulders above even the "not from concentrate" standardized juice, much less the orange juice concentrate I grew up with.

My mother was born and reared in Florida, and had relatives who owned an orange grove. Not until now did I stop to think about what a come-down it must have been for her to move to New York and subject her children to even the best concentrate. But those were the days when concentrate-making juice plants were a high-tech miracle for both growers and consumers.

The juice on the left? Nectar of the gods. Home-squeezed from the fruit of our own Page orange tree. So technically not orange juice, since Page oranges are actually 3/4 tangerine and 1/4 grapefruit—being a cross between a clementine and a tangelo.

Out of this world.

I love cooking shows. Most of them are on cable television, which we have never had and I hope will never feel the need to have, but they're a favorite of mine when available on long overseas flights. And then there's YouTube.

Ann Reardon's How to Cook That channel first caught my eye because of her "debunking" videos, in which she tries out and exposes too-good-to-be-true internet "hacks," mostly related to her specialty, food. Here's one (16 minutes).

And here's one for our daughter who has always loved miniatures (6.5 minutes). So has Ann, and in her "Teeny-Weeny Challenges" actually bakes in her miniature kitchen.

These are just some of the sidelights of her channel, however. Mostly she focusses on amazing desserts, and has recently published a cookbook called Crazy Sweet Creations. Here's a basic video on working with chocolate (13.5 minutes).

Are you hungry yet?

Most of Ann's creations are too complex to interest me in attempting them, but they are fun to watch, and I can pick up some interesting tips and tricks along the way.

Permalink | Read 1662 times | Comments (0)

Category Reviews: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Food: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Inspiration: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] YouTube Channel Discoveries: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

Or 20 minutes to watch a video.

This feels more like a Japanese tea ceremony than baking.

This is from the BBC, perhaps more trustworthy than some news sites? Pretty funny, anyway.

Scientists studied more than 1,000 foods, assigning each a nutritional score. The higher the score, the more likely each food would meet, but not exceed your daily nutritional needs, when eaten in combination with others.

Of course, "scientists" is a meaningless designation, and it's not clear how the foods tested were chosen, but they later add,

Food selection, ranking and cost based on the scientific study “Uncovering the Nutritional Landscape of Food”, published in the journal PLoS ONE.

So presumably one could find out more details. Below are their top 100, followed by the designated nutritional scores. Note that 99 of the foods are from plant or fish sources—but take a good look at the food ranked #8. Food for thought.

- almonds: 97

- cherimoya: 96

- ocean perch: 89

- flatfish: 88

- chia seeds: 85

- pumpkin seeds: 84

- swiss chard: 78

- pork fat: 73

- beet greens: 70

- snapper: 69

- dried parsley: 69

- celery flakes: 68

- watercress: 68

- tangerines: 67

- green peas: 67

- pike: 65

- alaskan pollock: 65

- green onion: 65

- red cabbage: 65

- pacific cod: 64

- scallops: 64

- pink grapefruit: 64

- dandelion greens: 64

- frozen spinach: 64

- chili powder: 63

- basil: 63

- collards: 63

- clams: 62

- chili peppers: 62

- broccoli raab: 62

- kale: 62

- whiting: 61

- atlantic cod: 61

- mustard leaves: 61

- romaine lettuce: 61

- coriander: 61

- whitefish: 60

- fish roe: 60

- apricots: 60

- cress: 60

- chinese cabbage: 60

- sea bass: 59

- herring: 59

- parsley: 59

- fresh spinach: 59

- walnuts: 58

- red cherries: 58

- butter lettuce: 58

- cow peas: 58

- podded peas: 58

- plantain: 57

- navy beans: 57

- summer squash: 57

- coho salmon: 56

- blue fin tuna: 56

- eel: 56

- lima beans: 56

- taro leaves: 56

- green lettuce: 56

- green tomatoes: 56

- red tomatoes: 56

- paprika: 55

- chives: 55

- arugula: 55

- sockeye salmon: 54

- mackerel: 54

- grapefruit: 54

- golden kiwi fruit: 54

- green kiwi fruit: 54

- cayenne pepper: 54

- leeks: 54

- red leaf lettuce: 54

- green beans: 54

- perch: 53

- rainbow trout: 53

- sour cherries: 53

- pink salmon: 52

- pompano: 52

- kumquats: 52

- hubbard squash: 52

- carp: 51

- oranges: 51

- red currants: 51

- pomegranates: 51

- rhubarb: 51

- jalapeno peppers: 51

- winter squash: 51

- carrots: 51

- octopus: 50

- prunes: 50

- cantaloupe: 50

- water chestnuts: 50

- cauliflower: 50

- broccoli: 50

- brussels sprouts: 50

- burdock root : 50

- pumpkin: 50

- ginger: 49

- figs: 49

- sweet potato: 49

After reading the Occasional CEO's post on Moxie (My favorite line? "Moxie is the durian of carbonated drinks."), I was inspired to write about my favorite New England carbonated drink, Undina Birch Beer from Higganum, Connecticut. I'm not generally a fan of carbonated drinks, nor of alcohol for that matter, but this white birch beer, with its 1% alcohol content, was exceptional. And nothing like the darker birch beers I had tasted in other parts of the country.

This Haddam Historical Society webpage has a small section, "Granite Rock Springs/Undina Soda," on the Undina Beverage Company and their white birch beer.

In the 1870’s Otto Carlson started making commercial root beer and birch beer in Swede Hill (upper part of Christian Hill Road) in Higganum. Carlson had a nostalgic longing for a drink remembered from his boyhood in Sweden, ‘bjord drick’ made from sap tapped from Sweden’s prolific birch trees. Not having enough birch trees around Higganum for commercial scale tapping, Otto developed a formula using cut up birch trees and steaming out their oils and juices. This became the commonly used commercial method of producing the popular birch beer.

Who knew white birch beer was Swedish? With all the Swedes on Porter's side of the family, it's no wonder the drink was a favorite. Sure seems a shame to cut up a tree to get it, though. Maybe we can have commerical birch groves for tapping like maple trees.

Needing a large quantity of water for his company, Carlson discovered a large bubbling spring in a cleft of granite rocks on the western slope of Ladder Pole Mountain in Higganum. This was “pure spring water,” above and beyond any possible contamination. Granite Rock Springs was 450 feet above sea level, up hill from Otto’s shop and overlooking the present Route 81. Otto Carlson named his beverage company UNDINA, meaning the Goddess of Water.

A write up on the spring notes that the “no part of its watershed is exposed to the seepage of cultivated fields or the impurities of inhabited areas. Its home is in the wild heart of nature and it gushes forth, a living, crystal clear stream of pure, soft water, a stream so large as to form the source of a mountain brook that is never dry but continually leaps and dances down the mountain-side until its waters finally join those of the Connecticut.

This delightful spring was used to make their white birch beer until 1980, when production outstripped its capacity. I could tell you that I noticed the difference, but that's probably stretching memory too far.

In the early 1900’s Undina was a popular brand of soda pop, with white birch beer its most popular flavor. Undina was distributed throughout Middlesex County and other parts of Connecticut and upstate New York. ... In 1945 Undina Beverage Company was purchased by Carl Anderson of Higganum and Eric Johnson, both of whom also remembered the cool refreshing ‘bjord drick’ in Sweden and took pride in maintaining production of the white clear drink.

Still Swedish!

By the 1950’s Undina Bottling Works was thriving and producing 500 cases of soda per day. It remained at the same site as Carlson’s original shop, although the extraction was no longer done there. In 1960 the company was purchased by Middletown residents Trean Neag and Fred Norton.

No longer Swedish except in origin. (Neag was Romanian; Norton I couldn't trace back far enough to find out.) The American Melting Pot in action!

The article doesn't mention when Undina closed. It was after our children were old enough to fall in love with their white birch beer, but much too long ago to pass that on to their own children. It sure was a sad day when they closed. I've heard that it lasted till Fred Norton retired; I'm sure the economics of running a small, local business in the days of soda behemoths contributed to its demise.

Perhaps now that microbreweries have become so popular and successful, someone will attempt to revive Undina. I hope so. You can still buy white birch beer if you try hard enough, and I'm grateful for that. But of course it's not the same.

This year my children and my husband got together for an entirely different kind of Mother's Day treat: a selection of Jeni's Ice Cream delivered in dry ice to our door.

My favorite Connecticut ice cream store, Grass Roots, had an ad on Facebook that said, Your momma called: she wants Grassroots ice cream. I laughed in appreciation when I saw it, knowing that my sister-in-law might get something from Grass Roots for Mother's Day, but it was out of the question for me.

And then this happened. It wasn't Grass Roots, but it was delicious and had the Grass Roots approach to unusual flavors.

First, of course, we played with the dry ice. It's much more fun if you have grandchildren to share it with. And to no one's surprise, there's a lot less dry ice left when it's delivered to Florida than when it's delivered to New Hampshire. Still, we enjoyed the moment. Here's the short version.

Now for the ice cream itself, in order of our trials. Boy, was that the wrong word. It was hardly a trial to enjoy these treats!

Blackout Chocolate Cake A chocolate ice cream quadruple threat with cake, extra-bitter fudge and chocolate pieces. Fantastic. Rich, darkly chocolate. Better than Publix's Chocolate Trinity? I don't know. Give me a large bowl of each side by side and I'll see what I can figure out. It might take several experiments....

Brown Butter Almond Brittle Brown butter almond candy crushed into buttercream ice cream. Is is possible that there could be something better than chocolate? I found this only moderately promising from the description, but oh, my what a flavor! A little almond, a little caramel, a little reminiscent of the wonderful milk ice cream we ate in Japan. It's subtle, but may even be my favorite of the Jeni's flavors, since Publix does so well in the chocolate department.

Skillet Cinnamon Roll Dark caramel, cream cheese, pastry, and cinnamon (lots of it). Not in the same league as the first two, but definitely good. If I liked cream cheese frosting more than I do, it might be great. I'd happily eat it again.

Caramel Pecan Sticky Buns (Dairy-Free) Rich coconut cream loaded with sticky bun dough, dark caramel, and roasted pecans. Fortunately, Porter liked this. It was far from his favorite, but he certainly made sure it wasn't wasted. I'm glad I tried it, but in a word, no. First, the "dairy-free" label is a big warning sign, and makes me think fake from the beginning, with overtones of margarine, artificial sweeteners, and decaffeinated tea. Then there's the c-word: coconut. I enjoy coconut in savory Indonesian dishes, and that's about it. Not at all in anything sweet. Pecans are another thing I like only in certain contexts (like salads) but desserts is not one of them. Sticky bun dough and caramel? Now those are winners, but frankly the overwhelming flavor was coconut—which is why Porter liked it and I didn't.

Pineapple Upside Down Cake Sweet-tart pineapple with golden cake, red cherries, and a caramel swirl. This is what I opened when I turned the coconut-flavored ice cream over to Porter. It seemed fair: he doesn't care much for pineapple; I do. This one was smooth and delicious, but the other tastes were overwhelmed by the pineapple.

Lemon & Blueberry Parfait Tart and uber creamy lemon with from-scratch blueberry jam in fresh cultured buttermilk and cream. Delicious, and the lemon makes it very refreshing. I love lemon, and this has an excellent flavor, but it does overwhelm the blueberry.

Sweet Cream Biscuits & Peach Jam Buttermilk ice cream, crumbled biscuits, and swirls of jam made with Georgia peaches from "The Peach Truck." Very yummy. The biscuits are noticeable by both taste and texture, just about the right amount in each case. The peach flavor is excellent.

Salty Caramel Fire-toasted sugar with sea salt, vanilla, and gress-grazed milk. A perfect balance of salty and sweet. This also was delicious, though I'll admit it was even better when paired with some Chocolate Trinity. I love the combination of chocolate and caramel.

Brambleberry Crisp Oven-toasted oat streusel with sweet-tart bramble berry jam of blackberries and blackcurrants layered throughout vanilla ice cream. I'm running out of things to say other than "delicious." But that it was. The vanilla is a better foil for the berries than lemon was for the blueberries. The oat streusel is reminiscent of a good-quality granola or an oatmeal cookie.

If I were to be blessed with such a gift on another occasion, what would I want to repeat? Any of them except the dairy-free variety would be welcomed, but Number 1 on my list would clearly be the Brown Butter Almond Brittle. It was the biggest surprise of all the flavors, and the most memorable. If there's an equivalent elsewhere I haven't found it.

I went over to the Jeni's website to check out some of the other flavors they offer. I'd definitely want to try their Gooey Butter Cake, in honor of our most pleasant visit to my nephew when he lived in St. Louis. Maybe Churro, or Cream Puff, or Boston Cream Pie, or Pistachio & Honey. Texas Sheet Cake and Dark Chocolate Truffle sound good, but both are dairy-free so I would steer clear of them. Porter would love Goat Cheese with Red Cherries, but I don't think I'd offer to help him finish that pint.

Brown Butter Almond Brittle aside, the best part of Jeni's is the variety and the opportunity to taste unusual flavors. I'm really thinking Grass Roots should get into the delivery business. :) Or maybe not; to do that they might have to grow too much and lose their small, local-business cachet. But it's a thought.

Despite my firm intentions to capitalize on the need to stay at home, I have not recently been accomplishing much. The world has been turned upside down and I'm finding it hard to stay focused on anything. On top of my own frazzled state, interruptions from distant family have greatly increased. They're all distant at this point—and that's harder than usually to take because in just one week we were supposed to have begun to gather most of them together here! The interruptions are most welcome and most treasured, but it's hard to work when every call, every text, every e-mail, every WhatsApp, every form of contact suddenly feels urgent.

I was at sixes and sevens all yesterday, but I made a concerted effort to have one finished task I could point to at the end of the day: I made barbecue sauce.

For years our favorite barbecue sauce was Jack Daniel's Original Old No. 7. But for months now I haven't been able to obtain it, and I became determined to make something similar of my own. Inspired by discovering the remains of a bottle of Scotch whiskey in our cupboard, I decided that yesterday would be the day. It was Cutty Sark, not Jack Daniel's, but I will hereby shock and alienate all aficionados by insisting that "whiskey is whiskey."

I found several "Jack Daniel's Barbecue Sauce" recipes online, took what I judged to be the best of each one, added a few twists of my own, and cooked it up.

In testimony to my frazzled state, it took me two tries. I hadn't gotten very far on the first one when something interrupted, and it ended up burning on the stove, making an awful mess of the pan.

After some extensive clean up work, I was able to see Try #2 through to the end.

Oh, was it delicious! Yes, I do say so myself. I think that even if I do find the commercial kind again, I won't look back. This is 'way better. The flavors bring to mind—of all things—the description in C. S. Lewis' Screwtape Proposes a Toast of devil's wine made from "vintage Pharisee": Look at those fiery streaks that writhe and tangle in its dark heart, as if they were contending ... forever conjoined but not reconciled. The flavors mingle without blending. It's sweet and sour, salty and smoky, smooth and rich with a bit of fire. No one impression dominates; each takes its turn coming to the forefront.

Whiskey Barbecue Sauce

- 1/2 cup plus 1 - 2 tbsp whiskey

- 4 cloves garlic

- 1/2 cup onion

- 2 cups ketchup

- 1/3 cup white vinegar

- 3/4 cup molasses

- 1/2 cup brown sugar

- 1/4 cup tomato paste

- 3 tbsp Worcestershire sauce

- 1/2 tsp smoked Spanish paprika

- 1/2 tsp hot paprika

- 1/2 tsp freshly ground pepper

- 1/2 tsp Kosher salt

Put both garlic and onion through a garlic press. Add with whiskey to a medium saucepan and heat gently for about five minutes.

Combine remaining ingredients, mix well and add to saucepan. Bring just to a boil, then reduce heat and simmer for 20 minutes or so.

Stir in remaining whiskey and simmer for another five minutes. Bottle when cool, and refrigerate.

Using the garlic press on both the garlic and the onion was my idea, and I think it works well. The sauce ended up silky, with no blending necessary.

Initially I resisted using ketchup, figuring that I ought to be able to make the sauce from tomato paste alone. But all the recipes I consulted used ketchup, and the clincher was that my tomato paste stock was low and we had lots of ketchup. Since ketchup is pretty much a staple around here, why not use it?

None of the online recipes call for smoked Spanish paprika and hot paprika; Liquid Smoke and bottled hot sauce seem popular. I used what I had hanging around, and am pleased with the result. I suspect there's a fair amount of flexibility here if you can't get the named ingredients. If Worcestershire sauce is unobtainable, for example, try a dab of anchovy paste or some fish sauce.

Enjoy!

We all know that sopranos specialize in hitting high notes. How about this one, reported by Stephan, who sings in a Catholic Church choir in Switzerland. He's not Catholic, but they have the choir! And the food, apparently.

The sopranos treated us to hors d’oeuvres and a six-course dinner for our choir’s annual general meeting. Beet carpaccio with goat cheese and honey; mushroom soup; pike-perch with saffron sauce, shredded leek, and wild rice; blood orange Campari granita; angus roast with pea sauce, celery-potato mash, and vegetables; and chocolate mousse with orange sauce and filleted orange wedges on the side. Of the hors d’oeuvres, the pear crisps with cream cheese, Gorgonzola and walnuts deserve a special mention.

That's setting the bar pretty high. Will the tenors provide the next feast?

If you have a spare 15 minutes, I highly recommend listening to part of this "Fake Food" podcast from Christopher Kimball's Milk Street Radio. The relevant section starts at about 18:30. Here are a few high(low?)lights:

- More money is made in food fraud worldwide than in narcotics trafficking.

- In light of the above, it's not surprising that food adulteration is big organized crime business, all over the world.

- Daffodil extract has been added to sunflower oil to make it look like olive oil.

- Parmesan cheese has been adulterated with shredded cardboard.

- When demand for a product of limited availability surges, fraud follows. (When coconut products became popular, what sold as "coconut water" was often just water, sweetened. You can't get more coconut palms fast enough to meet the increased demand.)

- 25% of the oregano sold has been adulterated. In Australia, that's 70%. (That really makes me appreciate the live oregano growing in our front garden.)

- Often even if the adulterants are theoretically not harmful, e.g. shredded olive leaves in oregano, they can be dangerous—olive leaves are often drenched in pesticides.

You get the depressing picture. The good news? Food scientists are getting better at detecting adulterated products, and someday soon your phone may have an app for that.

Ramblings inspired by a glass of milk:

America, the land of Liberty. New Hampshire, the state with the motto, Live Free or Die. Sometimes I wonder what our Founders would think of our current willingness, even eagerness, to give up essential freedoms for (supposed) safety. But then I realize that people are much the same in every generation, so I'm sure they had to deal with plenty of the same kind of opposition.

Am I going to complain about the current attacks on our Second Amendment? Not now, even though I—with a lifelong dislike of guns—find the attempts to disarm American citizens appalling and frightening.

Not this time. Right now I'm standing up, as I have before, for the freedom to enjoy flavorful foods.

I insist that one culprit in our "obesity crisis" is that Americans are unconsciously craving the flavor of normal, healthy food. Food such as the "farm milk" we drink when we are in Switzerland: fresh from the cow, unpasteurized, unhomogenized, just real milk. Real milk that bears only a superficial resemblance to that of the same name purchased in an American grocery store.

At home, I love milk, and drink a lot of it. But I can only drink skim; whole milk sticks in my throat. Except in the form of hot chocolate, which is best with whole milk, even in America. In Switzerland, farm-fresh whole milk is absolutely delicious without any chocolate at all. (Granted, with a piece of dark Toblerone on the side, it is even better.)

There's no comparison between "real food" and that which comes from the average grocery store. Not only is grocery store food highly processed, but it is also deliberately homogeneous, so that there's no variation in flavor—milk is milk, orange juice is orange juice, apple juice is apple juice, chicken is chicken—instead of celebrating and enjoying nature's bountiful variety.

Don't get me wrong: there's a lot of benefit that comes from our mass-produced food, including lower prices. It is, indeed, what they call a First World problem. My objection is not to the availability of such food, but that it is crowding out the small, the local, the variety, the food of tremendous flavors. Worse, the awesome food—food that was plentiful as recently as 30 years ago—is now often illegal in America.

As with many roads to hell, this one is paved with good intentions. Safety is not the only issue—profit is another, as is the fickle American public—and safe food is important. But our approach to safe food reminds me of that old Chinese proverb, Do not remove a fly from your friend's head with a hatchet.