The State Department has issued travel warnings for Israel (Level 3, "Reconsider Travel") and Gaza (Level 4, "Do Not Travel"). Not insane, though a bit generous, I would think: other than high-level diplomats, military personnel, journalists, and people with dire need, who in his mind would travel to an active war zone, which clearly includes all of Israel, not just Gaza.

What makes it very odd, in my mind, is knowing the greater picture: not long ago, many of the world's countries, including safe, first-world Switzerland, were given the dreaded Level 4 Do Not Travel status. Because you might catch Covid there. Never mind that you could just as easily catch Covid by staying home. And that for someone who is healthy enough to travel, the consequences of catching Covid are a whole lot less significant that the consequences of being blown up by a missile or a bomb, or raped/killed/kidnapped by a terrorist.

As I've said before, the Level 4 warning is so broad as to be almost meaningless. It needs to be re-evaluated.

I've featured the Lex Fridman podcast once before, his interview with former Soviet spy Jack Barsky. Fridman's podcasts are an amazing experience, not only because Fridman is both very intelligent and very interesting, but because he features guests who are the same. I'm not sure if he just choses exceptional guests, or if his interview technique makes them interesting. One thing I love: he lets them talk. No sound bites here. Fridman brings up a question, and he lets his guests run with it. Unfortunately, the side effect is that his shows are three hours long. But at least they work well split up into parts, which is what we usually do.

This video is from his interview with Canadian psychologist Jordan Peterson. Of course it is all interesting! But what I'm highlighting here is Peterson's personal diet, probably contrary to his wishes, since he says he doesn't like to talk about it and doesn't generally recommend it. The relevant part of the video is 2:03:06 to 2:10:19. This segment was introduced earlier, when he was asked if he started his day with coffee, and he replied, "Steak and water."

All this is very interesting, but the real point of this post is this steak that our oldest grandson just made with his new steam oven:

And this, also made in the steam oven, is why I'm not excited by Jordan Peterson's diet, even with infinite steak.

Earlier this week I both took a Covid test and wore a face mask for the first time in a long time. I hadn't been planning to do either.

I really didn't think I had Covid. I had a wicked sore throat, and barely any voice, so I wasn't going to church anyway, but I finally decided to take the test. If it turned out negative, Porter could reassure choir members that I hadn't exposed him—at least not to that—and if it were positive, I would have the reassurance that I was being given an immunization better than any vaccine could.

Taking a Covid test is a lot less stressful if you really don't care about the result.

As I had expected, it was negative.

For some reason, that knowledge didn't help either my throat or my voice. Covid-19 must not be the only virus game in town. At least I had the "it's not Covid" reply at the ready should anyone ask.

The face mask? That was because I had to go to the grocery store. I know masks are no longer considered particularly useful at stopping the spread of viruses, but it was completely effective for what I asked of it: encouraging other people to keep their distance, and shielding me from their dirty looks should I be afflicted by a sneeze or a cough.

The only really scary part of the experience was how normal the mask felt after the first few minutes.

Awesome news.

I just learned that one of the young doctors in our family is going into the field of pediatric allergies, and I can't be happier. Brilliant as she is, I don't expect her to find all the answers to some very complex questions, but I'm thrilled that she thinks the problem worth working on.

For decades I have been wondering: What is causing the great increase over my lifetime in allergies, autism, and autoimmune disorders? Growing up, I'd never even heard of someone allergic to peanuts, and now I'll bet everyone knows at least one person who is. In my day (by which I mean not only my childhood and earlier but my children's childhood as well), peanut butter and jelly sandwiches were even more of a childhood staple than chicken nuggets later became. I suspect everyone today also knows someone on the autism spectrum—a lot more than one that if you live in Silicon Valley or the Seattle area. I hear the location association often blamed on "nerds marrying nerds," and I'm sure that's a factor, but hardly the only, or even the biggest one.

Throwing the net wider now than the three A's I mentioned above, it's my impression that, despite decades of medical advances, children are in general significantly less healthy than they were when I was a child. We were, in some ways, a lucky generation. Antibiotics were new and therefore very powerful. Vaccines were vanquishing dangerous diseases like smallpox, diphtheria, whooping cough, and polio; tetanus was no longer routinely killing infants. (I'm one of the few people remaining who may still have a residual advantage over the general population if we ever get an outbreak of smallpox.) Improved sanitation had largely freed us from other dread ills, although in the case of polio it was a mixed blessing.

We also mostly had mothers who both were there for us day and night, and yet encouraged us to spend most of our free time playing outdoors, roaming the neighborhood, exploring the nearby woods, until dark and without sunscreen. (Yes, we did have and use sunscreen on the beach when visiting Florida, but never, as happens these days, for the hours and hours we spent outside at home.) We didn't have "devices" that encouraged us to live indoors, except for books and games, and even so we were frequently admonished to "go outside and get some fresh air and sunshine."

We had school, which was bad enough for our health, but it rarely intruded on our after-school lives. We did not have social media, and our parents were married (to each other). I didn't meet someone whose parents were divorced until I was a sophomore in high school. Our parents had a different approach to cleanliness, too. Environmental dirt was mostly considered "clean dirt"—there were no antibiotic soaps or cleaners, and if we washed our hands after using the bathroom and before meals, we were good to go. Hand sanitizer was non-existent in our lives. Face masks? They were for surgeons, not children. Catching measles, mumps, German measles (now generally known as rubella), and chicken pox was about as routine as catching a cold, except that we didn't have to stay out of school for a cold. And most of us caught them all in kindergarten despite the mild quarantine. Best "vaccination" I ever had: my rubella titre was still extremely strong after I graduated from college; for all I know, it still is.

"Artificial foods" were on the rise, but for the most part we knew where our food came from; not all, but most of our milk, fruit, and vegetables were local, fresh, and more nutritious than what our children are eating today. Sadly, I didn't grow up with access to raw milk, but our home-delivered milk was at least not homogenized. We had local stands that sold their own fresh-from-the-field fruits and vegetables, quite a contrast to the "farmers' markets" that I can shop at today, which are likely to have more craft booths and out-of-state (or country!) produce than local food. This was changing rapidly, but our food was still much more likely to have natural, beneficial microorganisms than artificial chemical preservatives. "Convenience food" was virtually non-existent, and any kind of restaurant meal very rare.

Then again, we also had very unnatural childbirthing, and doctors who actively encouraged mothers not to breastfeed, and clouds of radioactivity passing overhead, and margarine. No generation has all the advantages. The point is not so much that our childhoods were idyllic as that they were very different, and sorting out what factors might contribute to the rise in allergies, autism, and autoimmune disorders cannot be easy. "Welcome to complex systems."

Here are a few possibilities that I, as an experienced layman, think might be contributing to our children's diminished physical, mental, and emotional health:

- Nothing. The apparent increase in frequency of these afflictions is not actually real, but an artifact of the fact that we've started to pay attention to them, and perhaps changed a few definitions along the way. I used to accept that as an answer, but I'm no longer buying it. It's too much, too pervasive, and we don't dismiss other diseases just because we're paying more attention to them. There are more cancer cases showing up in part because more people are living to get cancer, instead of dying of something else earlier. And our new technologies are making us more aware of the disease at earlier stages. But that doesn't mean that there hasn't been a real increase in cancers, nor that cigarette smoking, chemical spills, bad diets, and radiation aren't significant factors in that rise.

- Greatly increased quantity, frequency, and complexity of routine vaccines. (Have we saved them from traditionally rare and/or mild childhood diseases only to saddle them with life-long disabling conditions?)

- Too little challenge to children's developing immune systems (variations on the "hygiene hypothesis").

- Breastfeeding may have made somewhat of a comeback since I was a baby—at least it's no longer routinely discouraged by doctors—but for most nursing is vastly different from the experience of past generations, which were exclusively breastfed for many months and continued to enjoy this transfer of benefits from the mother's own immune system till age two or three.

- Children are spending much less time outdoors, which by itself comprises many changes: less exercise; less exposure to sun, wind, rain, and other vagaries of nature; less interaction with wild animals and plants; less chance for independent action and exploration; less opportunity for social interaction in the form of pick-up games; less time for solitary walks and thought, for staring at the sky and watching the clouds—each of which is actually a broad spectrum of experiences which no amount of vitamin D supplement, Discovery Channel videos, organized sports, and zoo, garden, and museum visits can replicate.

- Smaller families. It's a lot easier to say, "go out and play," when you several children, and your neighbors have several children each; not only are your children almost guaranteed to find playmates, but there's safety in numbers; if someone gets hurt there will most likely be people there to help, and to run for additional help if needed. Large families also have a built-in support system—ask anyone who found his family isolated under COVID restrictions.

- Hidden environmental toxins. Certain kinds of pollution have been cleaned up beautifully since my earlier days—our air, rivers, and lakes look a lot cleaner, and we're much more careful now about heavy metals and radioactivity—but they're full of less obvious but perhaps more harmful junk, such as herbicides that have been shown to change male frogs into females. What could go wrong with that?

- Changed eating habits. Unbalanced diets, artificial colors and flavors, lack of micronutrients, excessive processing, accumulated pesticides, unhygienic conditions along the food chain, allowing children to be picky eaters, Coke for breakfast, eating on the run instead of at the family table—any number of factors could be trivial, or highly significant.

- Unstable family situations. A good family may be the best predictor of good health.

- Repeated exposure, at earlier and earlier ages, through social media, movies, television, books, video games, school, peer conversation, and even personal experience, to levels of violence, sexual content, adult acrimony, and general divisiveness—once experienced only by children in truly appalling situations, such as war zones.

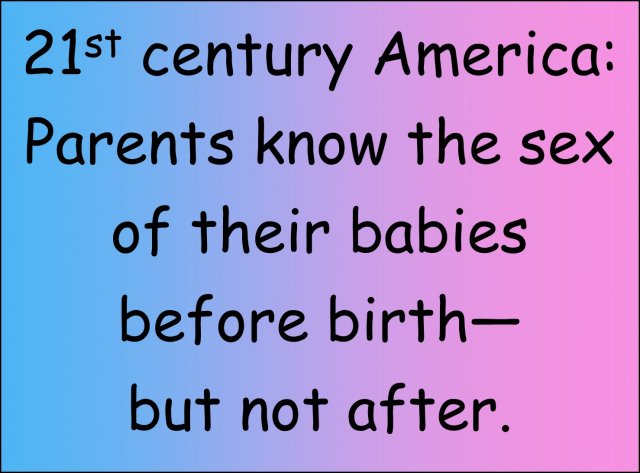

- Stress levels for children at an all-time high, again excepting the rare appalling situations. What's more, many of their stressors are novel—our bodies have been training for eons to deal with periodic starvation, but being bombarded daily with tragic news from all over the world, not to mention having to decide whether one should be a boy or a girl, is not something we've been equipped to handle. This kind of stress has physical as well as mental and emotional effects.

I'm sure you can easily add to this list.

Of a few things I'm certain: (1) Our children's mental and physical health is in serious danger, (2) there is not one clear culprit in this tragic situation, but an interaction of many factors, and (3) as a society, our priorities are really screwed up.

While not denying climate change, nor the need for integrity in sports, nor our sins of the past, nor our inter-relatedness with other parts of the world, it's clear to me that we are spilling vast multitudes of ink, money, and angst on relatively distant and/or contested issues, while barely acknowledging the suffering and even death of children "right next door." There's been a remarkable improvement in prevention and treatment of adult cancers, but for decades almost none for children, probably because it isn't a research priority. We obsess over slavery from 200 years ago, but a film like Sound of Freedom, which brings to our attention the beyond-shocking world of modern-day slavery, not to mention pedophilia, child pornography, and the role of Americans in producing, facilitating, and consuming the evil, is mocked, derided, and trivialized by those with the most power and influence. (It's hard not to speculate that there might be some conflict of interest there.)

There's a place for training children to avoid the things they are dangerously allergic to, and for teaching compensatory strategies to those with autism spectrum disorders, and for developing new medications and strategies for dealing with autoimmune diseases. But it's high time we recognized that these are stopgap, third-best measures, far inferior to prevention and cure.

This Florida girl may have (re)learned that the Connecticut sun isn't as wimpy as it first appears. After some days when the temperatures often made it desirable to sit in the shade, and life was busy enough to keep me spending time both indoors and out, suddently we had an absolutely perfect Connecticut summer day: sunny and breezy with lower humidity and temperatures in the 70's. We also had lots of great company that tempted me to spend most of the day conversing on the sunny deck.

The next day there was a bit of pink on the tops of my knees and feet, and—perhaps with a little imagination—my cheeks.

Our daughter's high school friend—who happens to be our dermatologist—wouldn't approve, but I'm pretty sure I made a week's worth of vitamin D that day. :)

Permalink | Read 1003 times | Comments (0)

Category Hurricanes and Such: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Health: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Politics: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Children & Family Issues: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Just for Fun: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

How is trust broken?

It may be by a sudden betrayal, but often you wake up one day and realize that the perfidy has been a long time growing to the point where you finally put the puzzle pieces together.

Despite personal experience with some dedicated and excellent teachers, I reached that point with our educational system some 30 years ago.

It took a little longer with our health care system. About 25 years ago I began to have my doubts, a slow process that accelerated exponentially over the last three years. I feel blessed to have two physicians in our own family, but even they, being newly-minted, have a tendency to parrot the official lines they were taught in their establishment med schools. With time and experience, they will be great, but that doesn't mean I trust them to know best right now.

In the United States, thanks to our well-established educational rights and freedoms, it is relatively easy to obtain a good education while eschewing the conventional educational system. Not so with medical care. When you are extracted from an auto accident and taken to the hospital, that is not the time do insist, "leave me alone; I don't trust hospitals." Even if you really don't trust hospitals. I suspect that what a doctor told me many decades ago is still true: Doctors are very good at emergency medicine; it's their approach to health in between emergencies that you can't trust. I will elaborate in a future post on occasions where the medical establishment has failed in those interstices in my own life. For now, it suffices to say that, malgré a few wise and compassionate doctors I know personally, my faith in our medical authorities is at an all-time low.

This was driven home to me today in a way that caught me completely by surprise.

I've been sorting through old medical records, and wondered why a urinalysis would be concerned about nitrite levels. (I also wondered why urinalysis isn't generally done any more. It's been longer than I can remember since a doctor asked me for a urine sample. But that's also a question for another day.)

I posed the question to Google, and the Cleveland Clinic answered.

It seemed to me that the Cleveland Clinic should be as good a source as any, but their answer did nothing to bolster my waning confidence. True, they let me know that nitrites in urine can be a sign of a urinary tract infection, which answered my question. But the language in which this information was expressed made me want to flee as far as possible from this organization.

Bacteria in your urinary system cause nitrites to form in your pee. The bacteria enter your body through your urethra (the tube that carries urine out of your body). As a result, you develop a urinary tract infection (UTI).

The bacteria may travel to your bladder (the organ that holds urine), causing bladder inflammation (cystitis). From the bladder, a UTI can spread to your kidneys, the organs that make urine. This leads to a kidney infection (pyelonephritis).

Women and people assigned female at birth (AFAB) are more prone to getting nitrites in their pee. In fact, people AFAB are 30 times more likely than people AMAB to get UTIs. That’s because their shorter urethras make it easier for bacteria to enter the urethra and reach the bladder. Also, a person AFAB’s urethral opening is closer to the anus, where stool comes out. Exposure to poop containing E. coli bacteria is a common cause of UTIs.

You've got to be kidding me. Who do they think they are talking to? They leave you to infer from the context that "AMAB" probably means "assigned male at birth," yet think they need to explain what a bladder is?

And how am I supposed to have any confidence at all in a medical facility that uses an abomination like "people assigned female at birth"? Of all people, doctors ought to be clear about basic human biology. If the Cleveland Clinic believes that a birthing attendant's pronouncement can determine whether a baby is a boy or a girl, how can I believe anything else they might say?

(I mean, if a Supreme Court justice faltered when being asked to define the term "woman," you would certainly expect my faith in her intelligence and wisdom to be compromised, wouldn't you? Oh, wait—that really happened, didn't it?)

And what's this "pee" and "poop" business? Those are slang terms that might be used with very young children, or perhaps among close friends—certainly not by medical professionals who hope to be taken seriously!

Enough is enough.

I won't drink Bud Light. I won't buy Ben & Jerry's ice cream.

Big deal. I don't like beer, and I've long found Ben & Jerry's not worth the price, especially since they sold out.

I almost never buy spices from Penzey's—previously my absolute favorite spice source—having found alternatives that aren't deliberately offensive to half their potential customers. I still buy King Arthur flour, because it's simply the best I've found, but the company has become more aggressive in pushing their political positions, and that has left a bad taste in my mouth—maybe not the smartest move when you're a food company.

Or any company.

I get it. Corporations are run by people, and people have opinions and favorite causes. A business can seem like a very handy bulldozer with which to push those opinions and causes. But behavior that may be appropriate for individuals and small businesses is annoying (or much worse) when adopted by large companies.

Corporations: You want to make the world better? I have some suggestions for what to do with your money and influence. Do these first, before throwing your weight around in places that have nothing to do with your business. And if you can, do it quietly, without blowing your own trumpet too much, please.

- Think and act locally. Make your community glad to have you as a neighbor.

- Provide good jobs, and pay your employees fairly. You have extra funds? Give them a raise, or at least a bonus.

- Improve working conditions. Consider not only physical health and safety but mental and social health, and opportunities for autonomy and initiative.

- Clean up your act. Wherever you are, make the water and air you put out cleaner than that which you took in. (Until the late 1960's, my father worked for the General Electric Company in Schenectady, New York, and I've never forgotten his comment that the water that went back into the Mohawk River from their plant was cleaner than what they had taken out of it. Whether that said more about GE's water treatment or the state of the Mohawk at the time I leave to your speculation.)

- If you're a publicly-held company, don't forget your shareholders. Think beyond next quarter's numbers and work to make your business a good long-term investment.

- Return charity to where it belongs. Instead of using their money to contribute to your favorite causes, lower your prices and let your customers decide what to do with the extra cash. Maybe they'll contribute to their favorite causes. Freely-given charity is always better than forced charity. Maybe they'll even spend the extra money on more of your products, who knows? But being generous with other people's money doesn't make you virtuous, it makes you despicable.

- Improve your product. Are you making or doing something worthwhile? Then do it better.

Any or all of these business improvements would make the world a better place without controversy. I've never understood why a company would deliberately and aggressivly seek to alienate half its customer base, but that seems to be happening more and more frequently. Do they think those who appreciate their controversial stance will out of gratitude buy more to take up the slack? Do they think they can ride out a temporary downturn and that those who are offended will quickly forget and go back to "business as usual?" My cynical side thinks they may be right about the latter, but I also think we may be reaching a tipping point.

I'm not a fan of boycots, preferring to make my commercial decisions based on quality and price rather than on politics. But I sense, in myself and in others, a growing distaste for dealing with companies that have gone out of their way to make it clear they think I'm not good enough to be their customer. I still shop at Target, but I just realized that the last time was more than three months ago. I still buy King Arthur flour, but find myself less inclined to linger over their catalog and consider their other products. Penzey's still has some products I can't get elsewhere, and I won't rule out another purchase—but I find myself unconsciously doing without instead. Small potatoes, sure. What difference can one formerly enthusiastic customer make to such large corporations?

A big difference, if that one person is part of a groundswell of discontent. I think it's happening.

I call on all businesses to adopt my simple model of true corporate responsibility. If you want to see better fruit, nourish the world at its roots.

Permalink | Read 1140 times | Comments (0)

Category Health: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Politics: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Random Musings: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Conservationist Living: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Inspiration: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

I am not and have never been one who desires a "spa treatment." Manicures, pedicures, full-body massages, facials, being rubbed with weird-smelling oils—the very thought makes me shudder. Granted, I can't really say I don't like the experience, because I've never tried it. On the other hand, I've never tried running into a burning building, either, but I think I can safely say I'd rather pass on that experience.

It seems to be generally true that cruise ships and resorts include spa facilities. I've always avoided them as enthusiastically as I avoid the casinos, bars, and smoking areas.

And then came our Viking Ocean cruise.

What's the difference? This spa had a dry sauna, a steam room, a cold room (with "snow"), a cold-water bucket shower, and ... a cold plunge—a small, shallow pool of a temperature that reminded me of the Pacific Ocean off the cost of Washington. And, unlike all the other spa services, these didn't involve an additional charge.

All were interesting, but I soon settled into a routine I loved: time in the steam room, followed by (much less) time in the cold plunge, then back to the steam, then the cold, etc. On the first day, the experience took a lot out of me—just two in-and-out dips left me completely exhausted.

But also exhilarated. With each day, each dip, the cold became less of a shock, and I was able to stay in the water longer. If I'd been able to swim it would have been easier, but the tank was even smaller than a typical hot tub.

I'm totally amazed at how good it made me feel.

I was told that the steam room was 113 degrees, and the cold plunge 52 degrees. (If those seem like weird numbers, consider that they were originally given in Celsius.) It occurred to me that I could duplicate the experience at home with a hot shower and our pool, which has been known to get into the low 50's in the winter. So there's no need to go to a spa for it. Whether or not I will actually do it at home remains to be seen.

But from now on, if I'm on a cruise or at a resort with spa facilities, I won't automatically avoid them like the plague.

In a post from earlier this year, The Domestication of City Dwellers, Heather Heying expresses many of my doubts about the crazy new "15-minute cities" concept, along with some I hadn't thought of.

Fifteen minute cities are intended to reduce sprawl and traffic, facilitate social interactions with your neighbors, and give you your time back. If it took fifteen minutes or less to get to all the places that you need and want to go, imagine how much more possibility there could be in life.

You might well wonder how such remarkable results will be achieved. The answer is: through restricting automobile travel between neighborhoods, fining people who break the new travel restrictions, and keeping a tech-eye wide open, with surveillance cameras everywhere.

Apparently, say the promoters of fifteen minute cities, we need to promote access over mobility. In their world, the definitions are these: “Mobility is how far you can go in a given amount of time. Accessibility is how much you can get to in that time.” The same post further argues that “Mobility - speed - is merely a means to an end. The purpose of mobility is to get somewhere, to points B, C, D, and E, wherever they may be. It’s the 'getting somewhere' — the access to services and jobs — that matters.”

This is not just confusing, it’s a bait-and-switch. Speed is not the same thing as mobility. Being able to “get somewhere” is mobility. Mobility means freedom to move. This freedom has been undermined for the last three years, in many countries, under the guise of protecting public health.

Fifteen-minute cities would further restrict your freedom to move. Your ability to get anywhere will be restricted under the pretense of making it easier and faster to get everywhere that you really need or want to go.

Dr. Heying goes on to explain several of the problems with this reasoning, and the whole article is worth reading. Including the footnotes. But a few of her points immediately jumped out at me.

First of all, who decides what exactly it is that comprises "everywhere that I really need or want to go"? One dentist is just as good as any another, right? Once upon a time, one church (Catholic) was all that any town needed; who really needs churches of different Christian denominations, not to mention mosques and Hindu temples?

If there's a public school within 15 minutes of my house, certainly I don't need to send my kids to a private school that may be located outside my neighborhood? In fact, this 15-minute city idea has a strong odor of our American public school system—in which children must attend the nearest school, and parental choice in education is strongly opposed—writ large.

And how will these convenient services for "everything we need and want" be set up? Who gets to open a grocery store in which neighborhood? What if no one wants to open a store there? Will some neighborhoods have only government-run facilities? Will we have mega-stores with every variety of foodstuffs instead of family-run ethnic markets? Or maybe no stores at all, just Amazon Prime? Do we really want thousands of tiny libraries, art museums, and concert venues, each offering a tiny fraction of what is now available? Or will we be told that we should get all our culture and information online?

And worst of all: Granted, it would be wonderful if all our loved ones lived within 15 minutes of our homes. Imagine having all our friends so close, and grandchildren just down the street! But how will that be accomplished? Our friends and family are spread all over the globe. Of course I'd like them to be closer—but not at the cost of imprisoning them! Even if they were all forced to move into the same 15-minute neighborhood, how long could such a situation be sustainable? Population control on a massive and tyrannical scale?

Besides, anyone who has grown up in a small town knows not only how wonderful they are, but also how insular, parochial, and restrictive they can be. If our COVID lockdowns produced a massive increase in suicide and other mental health problems, just wait till we've lived in 15-minute cities for a generation.

And if in that one generation people have come to believe that living under such tyranny is normal and good—the only word for that is tragedy.

Permalink | Read 1001 times | Comments (1)

Category Hurricanes and Such: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Health: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Politics: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Children & Family Issues: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

I couldn't resist that subject title, because it certainly grabbed my attention as the lead-in to an excerpt from a conversation between Mary Harrington and Bret Weinstein. As I've often said before, the whole conversation (1.5 hours) is worthwhile.

In this one, you can see chapter divisions if you hover your mouse over the progress bar. (approximate starting times in parentheses)

- Feminism against progress - history (2:45)

- Disagreement over progress and liberation (9:00)

- Digital and sexual revolution (25:50)

- Sexual marketplace (43:10)

- Traditional gender roles and hypernovelty (50:10)

- Internet and silos (57:20)

- Libertarian approach to sex industry (1:00:00)

- Sex is not recreational (1:09:00)

- The patriarchy (1:17:00)

- Porn and sexual violence (1:26:45)

If I were to recommend an excerpt, I'd go from Libertarian approach to sex industry through the end.

Just two quotes for this; it's far to annoying to extract them from the audio.

At one time, children would have played a sport, and they would have been very passionate about it, and what has happened is that has been transmuted into an act of consumerism, where what you do is you support a team, or you are very avid about a particular sport that you watch on your television, and so instead of playing baseball you are consuming baseball...."

That doesn't seem related to the rest of the discussion, but they go on to tie it in with sex. I picked this one to quote because it makes an important, more general point about participation versus consumerism, and I immediately added music to the list. As one church musician told me, "In worship, of course I want the music to be excellent. But I'd rather have a little old lady plunking out notes on an out-of-tune piano than sing hymns with a professional sound track."

And here's the rest of the vegan bacon comment. Agree or disagree with the statement, you have to admit it's an unforgettable image.

Contraceptive sex is like vegan bacon; it's kind of the same, but is it any wonder that people are adding a lot of hot sauce? Because the flavor just isn't quite there.

A lot has changed in 35 years, and not all for the better.

Looking through some old journal entries, I read about a time when our five-year-old daughter spiked a fever at night.

She ran a fever last night. I don't know how high, but she was delirious [her not-uncommon response to fevers]. If it weren't so serious, it would be entertaining, listening to her describe the things she sees. Normally I would wait a few days to see what would happen, but things are so busy that I took her to the doctor, since if she were going to need an antibiotic, I wanted it started right away. But: "It's a virus, $32 please."

She can go back to school tomorrow. "Why not?" they said. "That's where she got it in the first place."

Can you imagine that scenario taking place today? Yet that's the way life was, and I think those were saner times.

Permalink | Read 949 times | Comments (0)

Category Education: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Health: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Politics: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Children & Family Issues: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

The 20th anniversary DarkHorse Podcast is full of apparently random interesting topics. If you have the time for the whole hour and 40 minute show, you can skip to about minute 11:30 to get past the ads. There is discussion of sea star wasting disease, then a very long section on telomeres and how both the New York Times (no surprise) and the New England Journal of Medicine (more concerning) recently managed to ignore critical information that was known 20 years ago.

I enjoyed those parts, but if you just start at 1:13:00 you'll get 26 minutes of really good stuff, I think. From finding truth in the words of people with whom you have serious disagreements, to the complex problem of moving forward without losing the good of what you've left behind, to why dishwashers that use less water might poison the environment by forcing the use of more and stronger detergents.

My favorite part, however, and the part I think some of our family members will appreciate, is the discussion of Elimination Communication at about 1:28:10, and the idea of the new mother's "babymoon" period just before that. (They don't use either of those terms, however.) Not that our famly will find anything new there—and it's been known for years among the homeschool/home birth/breastfeeding/raw milk/organic food/homesteading/etc. crowd. What's so interesting to me is that it shows up in this podcast, totally unexpectedly. In their naïveté about the subject, Bret and Heather get some things wrong (as their listeners were quick to point out) but they get a lot right, too, and at least they are aware of it, which most people are not.

Permalink | Read 1232 times | Comments (0)

Category Health: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Children & Family Issues: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Random Musings: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Everyday Life: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Conservationist Living: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

"Go play outside!"

So said generations of mothers—at least once we got past the eons of history in which both work and play generally took place outdoors by default.

Partly, that motherly admonition was meant to get us out from underfoot, but there was also a high respect for the value of "fresh air and sunshine" for health and growth.

No one had to tell me twice to get outdoors, not when there were trees to climb and a forest to explore. I've been an avid bookworm ever since I learned to read, but I was happy to do much of my reading on the platform my father had built for us high in the trees.

When did the outdoors become our enemy?

Being exposed to the sun was branded a high-risk activity for children, unless they were slathered in sunscreen—not just at the beach, but in their own backyards. Even then, playing outside was not encouraged, for it provided no relief for mothers, who were told they had to keep their eyes on their children at all times, lest they get hurt, or even kidnapped. How much easier and safer it was to keep them indoors, entertained by the magic of that handy babysitter, the television set—the gateway drug of today's "screens."

However, the tide may be turning, at least a bit. Parents are once again at least thinking about trying to get their kids outdoor time. They are struggling to believe with their hearts the statistics that show kidnapping by strangers and mass shootings to be minuscule risks in most of the United States, and the discovery that children need a bit of danger and challenge to grow up both physically and mentally healthy. More and more people are realizing that the advice we were given for avoiding COVID—stay indoors, and especially avoid playgrounds, beaches, and neighborhood walks—was likely the exact opposite of what we should have been doing. Ever so slowly we are recognizing that our mothers, grandmothers, and great-grandmothers may have been right when they told us to go out and play. Fresh air and sunshine are indeed our friends.

Here's another reason why:

It is dark inside your head, but even there, the sun does shine.

This is the beginning of Heather Heying's latest substack post about the great value of Near Infrared Radiation (NIR), those wavelengths of light just longer than red.

Most people have heard of the hormone melatonin, known for its regulation of the sleep-wake cycle. This is created by the pineal gland, and is called circulating melatonin.

But there is also subcellular melatonin, which, it turns out, is produced in the mitochondria of our cells, stimulated by exposure to NIR.

Subcellular melatonin is a powerful antioxidant. ... Oxidation is a ubiquitous and destructive process in organisms, a natural side-effect of metabolism. Antioxidants scavenge the free radicals formed by oxidation, thus mitigating its deleterious effects. Melatonin is a particularly strong and multi-functional antioxidant.

In the brain, melatonin’s antioxidant capacity is likely to be especially important, both because of the disproportionately high use of oxygen by the brain, and because some other antioxidant systems are not present there. Absent near infrared photons being carried deep into the brain, which then promote the synthesis of subcellular melatonin, brain function might go more than a bit haywire.

Subcellular melatonin also reduces inflammation, increases the rates of waste removal within cells, and has immunoregulatory effects. Furthermore, it improves mitochondrial function via several known mechanisms, and generally promotes health and vitality. And again, there is substantial evidence that NIR prompts its formation.

So how do we get this NIR to our mitochondria? Here's the good news:

- The majority of photons that reach us from the sun are actually in the NIR range.

- Unlike visible and ultraviolet light, NIR penetrates deep into our bodies, including our brains.

- The bodies of babies and young children are perfused with NIR.

- Cerebrospinal fluid distributes NIR photons deep into the brain.

- NIR comes to us not only from the sun, but also reflected off objects around us, such as the moon, leaves, snow, sand—they can reach us standing in the shade, fully dressed.

- Just after sunrise and before sunset are particularly good times to pick up NIR.

- NIR is also produced by campfires, candlelight, and incandescent bulbs.

The bad news?

- Because our bodies are thicker, the average adult gets less than 2/3 the NIR penetration children do. Just what we need—another good reason to lose weight.

- Most of the lighting that we modern people experience indoors (fluorescent, LED) does not provide this vital nutrient.

You can read Dr. Heying's entire article, with a lot more, and references, here.

For those who prefer a non-print source, here's an excerpt from the latest DarkHorse Podcast episode (#170) in which she introduces the subject. (approximately minutes 25:34 to 39:32)

As most of you know, David Freiheit (Viva Frei) has been my favorite Canadian lawyer since sometime in 2020. Even though he no longer practices law and subsequently fled Canada for Florida, for the sake of his kids. I haven't posted anything from him in a while, because, frankly, his explosion of fame following his livestream coverage of the Canadian truckers' Freedom Convoy has meant that I can't possibly keep up with him.

However, we recently made time for his 1.5-hour interview with Dr. Bret Weinstein, and except for the first three minutes, every second was worthwhile. We were even happy to listen to it at normal speed (which we have to do when watching it on television instead of on the computer) because the information content is dense.

Since most of you will find the time commitment untenable, please at least take ten minutes and listen to minutes 21 through 31, and Bret's story about the incredible discovery he made in his grad school research about cancer, longevity, and the laboratory mice used in drug safety testing. If that whets your appetite for the rest of the interview, so much the better.

Bret is an excellent speaker: clear, cogent, and riveting. Viva and the other host, Robert Barnes, are normally quite interactive with their guests, sometimes to the point where I wish they would shut up and let the guest continue speaking. Not this time. As one commenter put it, "Watching Barnes and Frei blink for 10 minutes or more at a time with their lips closed is so unnatural...." Bret is that interesting.

I've been watching Bret's DarkHorse Podcasts for quite a while now, and I still learned a lot here. Skip the first three minutes—after that it's gold.