This is the post I started to write five months ago, but postponed to make sure everyone involved got through their quarantines and other impedimenta successfully.

I like to think that we've been more careful than most during this pandemic, though more due to the concern of our children (who apparently think we are "old") than our own. But when you're retired, and introverted, and not easily bored, staying home is a pretty easy option. We wore masks before our county made them mandatory, shopped only for what we deemed necessities, and used the stores' "senior hours" when we could. I'm also the only person I know who consistently washed (or quarantined) whatever we brought home.

But all that isolation, particularly the lack of physical touch, is hard even on introverts.

Hardest of all was cancelling our big family reunion scheduled for April 2020—coinciding with what was supposed to be the first visit home in six years of our Swiss family. Following close behind were missing our nephew's wedding, our normal summertime visit to the Northeast, and our long tradition of a huge family-and-friends Thanksgiving week of feasting and fun, all of which would have involved being with most of our American-based family. Plus the breaking my fourteen-year streak of travelling overseas to visit our expat daughter and her family (one year to Japan, thirteen to Switzerland).`

I know that doesn't begin to compare with the hardship endured by those who were forceably separated from loved ones who were sick or dying. But when the "temporary measures to keep our hospitals from being overwhelmed" turned into unending months of restrictions—with our hospitals so far from overcrowded as to be financially strapped due to underutilization—even normally compliant people like us began to chafe.

Even as we relaxed and let go of much of our fear, we remained vigilant in our precautions, for a very good reason: a light, not at the end of the tunnel, but a much-needed illumination in the middle of the tunnel. We needed to stay healthy, because...

The reunion remained off the table, due to onerous quarantine requirements imposed by the states the rest of our family live in. But thanks to much work on their part, and a state government more enlightened than most, our European family was able to visit us in December. Rarely have I been so happy to be living in Florida, which welcomed them with open arms. So of course did we! Mind you, I think the CDC was still recommending we wear masks all the time with visitors and stay six feet apart, but naturally that didn't last six seconds! A year apart from family is far too long, and that goes tenfold for grandchildren. Sometimes you just do what you have to do.

We did the risk/benefit analysis—and made the joyful choice.

Porter had to drive to Miami to pick them up, because so many flights had been cancelled. But he would have driven farther than that to bring them home!

We had been prepared to stay mostly around the house, just enjoying each other's presence. And at first we did a lot of that, since merely being in America was adventure enough for the grandkids. But they were here for a month, and most of the tourist attractions had reopened, albeit at reduced capacity, so we took full advantage.

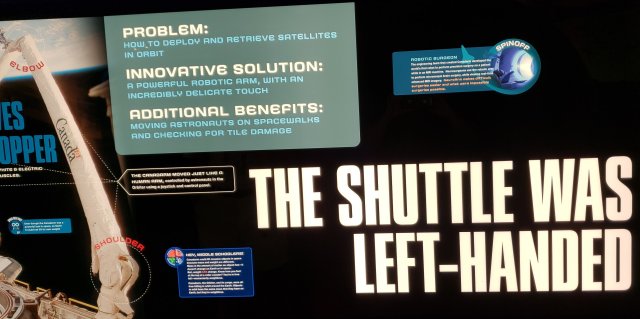

Kennedy Space Center was amazing. We were not the only visitors in the park, but at times it seemed like it. Sadly, some of the attractions were still COVID-closed, but there was certainly plenty to see. The following photo is for the lefties in our family:

One of the trips I enjoyed the most was to Blue Spring State Park, which was visited by more manatees than we've ever seen naturally in one place. The weather was perfect—that is, cold. Cold weather drives the manatees from the ocean and the rivers into the relatively warm water (about 72 degrees) of the springs. The air temperature made most of us keep our masks on even though that was not required except inside the buildings, since we discovered them to be very effective nose-warmers.

Another favorite activity was swimming. (Not with the manatees; that's no longer allowed.) The intent was for most of it to be in our own pool, and indeed it was, but there had been a glitch: We purchased a pool heater, knowing that our pool temperatures in December can dip into the 50's (Fahrenheit). However, the unit that was supposed to have been installed before our guests arrived was delayed again and again. Whether it was actually the fault of the pandemic is anyone's guess, but that's what took the blame. It finally arrived just a few days before they had to return to Switzerland. Until then, the children swam bravely, if not at length, in the cold water, and all of us enjoyed the (somewhat) heated pool at our local recreation center. And then they really appreciated our own heated pool for those last few days.

To be continued....

Permalink | Read 1464 times | Comments (1)

Category Hurricanes and Such: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Health: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Politics: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Children & Family Issues: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Everyday Life: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

I really don't like the way Mother's Day has been altered, morphing from a joyous celebration of and respect for our own mothers, to honoring all women who happen to be mothers, to making the day downright depressing by including everyone under the sun and telling many sad stories in the process. At every step the day seems to have become less meaningful and more selfish.

But in this world there are still plenty of sorrows associated with motherhood, and that suffering needs to be remembered. This was brought home again to me when I read this in The Wild Robot, by Peter Brown.

Do you know what the most terrible sound in the world is? It's the howl of a mother bear as she watches her cub tumble off a cliff.

This post is for every mother who has lost a child: at any age; at any stage of life; suddenly or through prolonged suffering; by accident, injury, illness, stillbirth, miscarriage, or abortion; and also for those who have lost even the hope and dream of children.

Even more so, this post is for mothers (and fathers) who have heard the howls of their own children who have suffered these losses.

Sunday is for celebrating what we have. Today we can pause to think about what we—or more importantly, others—have not.

Permalink | Read 1262 times | Comments (1)

Category Children & Family Issues: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

I realize that for very few of my readers is the question of whether or not a pregnant woman should get a COVID-19 vaccine of any importance. Nonetheless this is worth a post just because it is one of those laugh-or-cry articles.

The source is the School of Public Health at Johns Hopkins, which I generally respect. Here's a link to the whole article for those of you who seriously want the information. It's a serious business and an important decision to make.

For everyone else, however, here are a few snippets that caught my eye and inspired me to write. The bolded emphasis is my own.

Globally, over 200 million people are pregnant each year. Whether they should be offered the new COVID vaccines as they become available is an important public health policy decision. Whether pregnant people should seek vaccination is a deeply personal decision.

Note the term "pregnant people." The article goes out of its way, to the point of being very annoying, to avoid the term, "pregnant women." Exactly how many pregnant men have there been in the history of the world? I do, however, appreciate the acknowledgement that it's a personal decision, although later on the article seems to find a problem with that.

Evidence to date suggests that people who are pregnant face a higher risk of severe disease and death from COVID compared to people who are not pregnant. For instance, pregnant people are three times more likely to require admission to intensive care and to need invasive ventilation. The overall risk of death among pregnant people is low, but it is elevated compared to similar people who are not pregnant. Some studies suggest that COVID in pregnancy might be associated with increased rates of preterm birth.

There are still significant unknowns: How do risks vary by trimester? What are the risks of asymptomatic infection? Further, most current information about COVID and pregnancy comes from high-income countries, limiting its global generalizability.

Although there is not yet pregnancy-specific data about COVID vaccines from clinical trials, the vaccines have been studied in pregnant laboratory animals. Called developmental and reproductive toxicity (DART) studies, research with pregnant animals can provide reassurance about moving forward with vaccine research in pregnant people.

All three of these vaccines offer a very high level of protection against severe COVID. There is little reason to believe these vaccines will be less effective in pregnant people than they are in people of comparable age who are not pregnant.

The next sentence is the one that made me sure I had to write about this. It's the kind of thing I would have shared on Facebook, except that I'm trying to reduce my Facebook presence, so it goes here instead. With more words, naturally.

Professional societies, such as the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, the Society for Maternal-Fetal-Medicine, and the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists, all support COVID vaccination in pregnancy when the benefits outweigh the risks.

What, pray tell, does that say that has any usefulness? Who in his right mind would support something when the risks outweigh the benefits? So how is this a meaningful statement at all?

The absence of pregnancy-specific data around COVID vaccines continues an unfair pattern in which evidence about safety of new vaccines for pregnant people lags behind. This unfairness is ethically problematic in at least two important ways.

So, it's unfair because we don't have enough data on the effects of the vaccines in pregnancy? Would they have held back the vaccines until sufficient data had been gathered so that the information was "equal" for everyone? That would truly have been unfair to pregnant women, because letting the rest of the population get vaccinated helps them whether or not they feel safe getting the vaccine for themselves.

First, people may be denied vaccine, or may face barriers in accessing vaccine, because they are pregnant.

I agree that's a problem. Because the data is insufficient, in absence of a clear danger to mother and/or child in getting the vaccine, it should not be withheld from a woman who feels comfortable with it.

Second, even when pregnant people are eligible for vaccination, because public health authorities have not explicitly recommended COVID vaccines in pregnancy, the burden of making decisions about vaccination has shifted to pregnant people.

And where else should it be? Medical advice should not be handed down like commandments from heaven. People need the best information available, and the freedom to make their own decisions—even wrong ones.

Come to think of it, even commandments from heaven come with the free will to ignore them.

Permalink | Read 1356 times | Comments (0)

Category Hurricanes and Such: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Health: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Children & Family Issues: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Just for Fun: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

Porter alerted me to this interesting, though highly biased, view of what's necessary for successful learning at home. It's from a Geopolitical Futures report by Antonia Colibasanu.

According to an April 2020 report by the European Commission, more than a fifth of children lack at least two of the basic resources for studying at home: their own room, reading opportunities, internet access and parental involvement (for children under 10 years old).

We can ignore the absurdity of needing internet access to learn from home, because the context of the quote is traditional classroom schooling provided from outside to children at home, rather than education per se.

What struck both of us, however, is the first "basic resource": that the child should have his own room. Granted, a quiet place to work is a great thing, but I see no reason why that implies the need for single bedrooms. And, as my friend and sometime guest poster points out, school classrooms are hardly solitary spaces. Mind you, I'm not in favor of open-plan offices, but I find it amusing that one's own room is considered necessary for learning but currently out of favor in our trendier workplaces.

Public education from home is relatively new, but of course homeschoolers have been doing it for centuries (well pre-internet, I might add), and often in the context of large families in which shared bedrooms are common. What is required is not separate bedrooms, but discipline and respect for others. I'll admit it also helps to have the ability to concentrate in the presence of distractions, especially if you live (as our grandchildren do) in a family where someone is nearly always singing or playing a musical instrument. Our own children discovered that climbing a tree was a good way to get some undistracted reading time.

Further, this insistence on single bedrooms—with its implication of small family size—ignores the tremendous educational advantage of having multiple siblings. My nephew learned math far beyond his grade level because he wanted to keep up with his brother. Our younger grandchildren see no reason why they shouldn't be learning and doing what their older siblings are, and the older ones are usually happy to help them along.

Public education is a very confining box to learn to think outside of, even when the devil drives.

What current generations think of as ancient history is as alive as yesterday to those of us who lived through it.

A long time ago (1970's) in a galaxy far, far, away (the state of New York), a new mother innocently asked if it was normal to experience orgasm while breastfeeding. (It's not common, but it happens. Just as orgasm during childbirth sometimes happens. Not to anyone I know, though.)

These were days when natural childbirth was just beginning to gain popularity, and breastfeeding was still considered to be a bit weird, especially by doctors. The woman was reported to the authorities (some version of Child Protective Services) who decided she must be a sexual deviant. They forceably separated her from her baby. My memory of it is a bit hazy, but I believe it was after La Leche League got involved that the situation was resolved in the mother's favor—but by then she and her nursing infant had been separated for several days. The justification given by the authorities for their behavior, not to say their ignorance, was that it is better to falsely traumatize 100 innocent families than to let one potential evildoer slip through their hands. Sadly, this family was far from the only one similarly torn apart in those days. Maybe it's still going on; I don't know. I'm not as close to those issues as I was back then.

These memories came back in strength as I listened to this Viva Frei report. Freiheit isn't any happier than I am that COVID-19 is pre-empting so much of his law vlog, but needs must when the devil drives. Who indeed but the devil can be driving Canada to force apart law-abiding, healthy Canadian families—including very young children?

The Regional Municipality of Peel is near Toronto, Ontario. There the recommendations for what to do if someone in your child's class or daycare tests positive for COVID-19 include the following:

The child must self isolate, which means:

- Stay in a separate bedroom

- Eat in a separate room apart from others

- Use a separate bathroom, if possible

- If the child must leave their room, they should wear a mask and stay 2 metres apart from others

Remember that this includes elementary school children, and even those in day care. Very young children are to be isolated from their families—from their mothers!—for two weeks. Two weeks is a very long time in child-years.

And this is for children with no symptoms at all. What about those who are sick, whether or not with COVID-19? Is a child with an upset stomach to be left in his own vomit? What are these people thinking?

What child, even a healthy one, can endure 14 days of isolation without mental and emotional scars? In prisons, solitary confinement is a serious punishment. Freiheit makes the legitimate point that people who have been arrested on suspicion of having committed a crime have more protections than those who are suspected of possibly harboring the COVID-19 virus.

Another question comes to mind: Do all Canadians have big houses and small families? Or does the government plan to take away the children of people who don't happen to have a bedroom to spare for isolation? Apparently the fear that such official interference will take their children is driving some parents to comply with these horrendous rules. That and the $5,000 fine for non-compliance. If parents did these acts on their own they would be accused of child abuse.

I apologize if some of you think I'm being too alarmist, and maybe listening to too many YouTube videos. And yet I don't apologize—someone has to broadcast what's happening. Someone has to tell the victims' stories. Freiheit himself thought at first this had to be false news, but couldn't avoid the conclusion that it is all too real.

There is a little good news: apparently there has been enough outrage over these regulations that some politicians are now distancing themselves from them. It's an ongoing story. But one thing is for sure: If people don't speak up, the road from bad to worse is a swift one.

Concerned as I am with our society's loss of a culture of saving, when I found this short but accurate video on helping kids develop good financial habits I wanted to pass it on. There are subtleties to all of her points, especially #1, which can't be dealt with in a five-minute video, but the basics are sound.

Permalink | Read 1268 times | Comments (0)

Category Children & Family Issues: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

They say it's the winners who write the history books, implying that what has been written is untrue.

Nonsense. What it does mean is that it is not the whole truth.

But the solution to not enough truth is more truth. Labelling what has previously been written and taught as false—or erasing it altogether, and substituting another version with its own biases—only compounds the problem.

(I can hear the teachers now, pointing out that it's difficult enough to get students to learn any history at all, much less to absorb and ponder more than one point of view. But no one ever said good teaching was easy.)

I've mentioned before that one of the gravest consequences of simplifying the very complex Chinese written language is to cut off the common people of China from their literature and history. That is a very powerful tool in the hands of a totalitarian régime.

Nor are people living in a democracy safe. In the end, is there much difference between a people who cannot read their historical documents and those who do not? If free people don't care to keep their minds free, can tyranny be far behind? As President Ronald Reagan said, Freedom is never more than one generation away from extinction. It has to be fought for and defended by each generation.

Having just re-read, and reviewed, George Orwell's Nineteen Eighty-Four, I was especially struck when I came upon Larry P. Arnn's essay from last December, "Orwell’s 1984 and Today." As usual, I recommend reading the original; it's not long.

The totalitarian novel is a relatively new genre. In fact, the word “totalitarian” did not exist before the 20th century. The older word for the worst possible form of government is “tyranny”—a word Aristotle defined as the rule of one person, or of a small group of people, in their own interests and according to their will. Totalitarianism was unknown to Aristotle, because it is a form of government that only became possible after the emergence of modern science and technology.

In Orwell’s 1984, there are telescreens everywhere, as well as hidden cameras and microphones. Nearly everything you do is watched and heard. It even emerges that the watchers have become expert at reading people’s faces. The organization that oversees all this is called the Thought Police.

If it sounds far-fetched, look at China today: there are cameras everywhere watching the people, and everything they do on the Internet is monitored. Algorithms are run and experiments are underway to assign each individual a social score. If you don’t act or think in the politically correct way, things happen to you—you lose the ability to travel, for instance, or you lose your job. It’s a very comprehensive system. And by the way, you can also look at how big tech companies here in the U.S. are tracking people’s movements and activities to the extent that they are often able to know in advance what people will be doing. Even more alarming, these companies are increasingly able and willing to use the information they compile to manipulate people’s thoughts and decisions.

What we can know of the truth all resides in the past, because the present is fleeting and confusing and tomorrow has yet to come. The past, on the other hand, is complete. Aristotle and Thomas Aquinas go so far as to say that changing the past—making what has been not to have been—is denied even to God.

The protagonist of 1984 is a man named Winston Smith. He works for the state, and his job is to rewrite history. ... Winston’s job is to fix every book, periodical, newspaper, etc. that reveals or refers to what used to be the truth, in order that it conform to the new truth.

Totalitarianism will never win in the end—but it can win long enough to destroy a civilization. That is what is ultimately at stake in the fight we are in. We can see today the totalitarian impulse among powerful forces in our politics and culture. We can see it in the rise and imposition of doublethink, and we can see it in the increasing attempt to rewrite our history.

To present young people with a full and honest account of our nation’s history is to invest them with the spirit of freedom. ... It is to teach them that the people in the past, even the great ones, were human and had to struggle. And by teaching them that, we prepare them to struggle with the problems and evils in and around them. Teaching them instead that the past was simply wicked and that now they are able to see so perfectly the right, we do them a disservice and fit them to be slavish, incapable of developing sympathy for others or undergoing trials on their own.

As a young child, I received an allowance of 25 cents a week. (A quarter was worth a lot more 'way back then.) From that I was expected to allocate some to spend as I pleased, some for the offering at church, and some to be saved into my small account at the bank. That was the beginning. My family had a culture of saving, as well as giving and spending. Saving was for the future—for larger-ticket items, and for unknown future needs.

Part of the excellent advice I received from my father as I was establishing my own household was to set up a regular savings plan, not only for future purchases but to ensure that I could handle at least a six-month period of unemployment—preferably a full year. Of course it took some time to save that much money when I had all the expenses of newly-independent living to meet, but by making it a priority I soon had a comfortable cushion against unexpected expenses.

Fortunately, I married a man with similar views, which were not uncommon among those of us whose parents had lived through the Depression days. For a number of years we were blessed with two incomes, but made a point of keeping our standard of living low enough that we could live on one and save the other. This stood us in very good stead when disaster hit the American information technology industry, and so many IT workers lost their jobs because the work was transferred to India and other places overseas.

But somewhere along the line the culture of saving was largely lost. Once considered a virtue, saving is now called "hoarding" and held in contempt. It seems to be considered a patriotic duty to spend all one's money—and more. (If true, we have been bleeding red, white, and blue during this pandemic.) However, the ugly consequences of this attitude are nowhere more apparent than in the large numbers of families facing financial disaster due to pandemic-related job loss. So many people have gone in the blink of an eye from enjoying comfortable incomes to standing in bread lines. If they had been encouraged to follow my father's advice and maintain a savings cushion of a year's salary, they would likely have been able to weather this storm with ease. But no one—not the government, not the media, not the schools, not our consumerist society, and apparently far too few parents—has been passing on this essential lesson.

I hope it won't take another Great Depression to recover our lost wisdom.

Permalink | Read 1279 times | Comments (0)

Category Hurricanes and Such: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Children & Family Issues: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Random Musings: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

We're nearing the end of the year, and I've been (very pleasantly) inundated with more important ways to use my time than writing blogs posts (more on that later). That's not to say writing isn't important to me; indeed, I find it essential for my mental health. However, to everything there is a season, and this season is writing-limited. So it seems like a good time to some end-of-the-year decluttering of my collection of random ideas that can be dealt with relatively quickly. Here's one, a six-minute video by the remarkable Larry Elder that expresses well my own personal impressions of the effect of President Lyndon Johnson's "War on Poverty" (plus several other social factors), as well as what I learned during high school from Mr. Jim Balk, the most remarkable history teacher I ever had.

Permalink | Read 1324 times | Comments (0)

Category Children & Family Issues: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

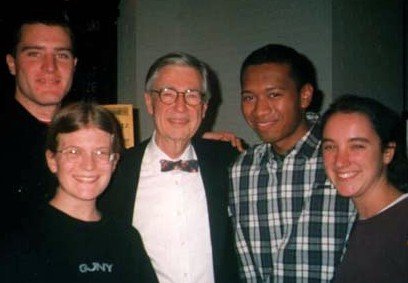

Feeling the time pressure here, so you you get a quick post today. I no longer remember how I happened upon this video, but the Mister Rogers' Neighborhood fans among you (including Heather, pictured below) and/or jazz fans might enjoy it even more than I did.

Permalink | Read 1403 times | Comments (1)

Category Children & Family Issues: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Just for Fun: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

I've been having fun cleaning out computer files, and came upon some old photos that may me wonder just how much our personalities are determined at birth or very early in our childhoods.

.jpg)

Here I am at age five, drinking water after enjoying a hike in the Adirondacks, wearing comfortable clothes and not sitting cross-legged. Comfort remains my highest criterion for choosing clothing, I have always loved spending time in the woods, water is my beverage of choice, and I have never, ever been able to sit cross-legged without serious discomfort.

Here's evidence from age six that my mother did her best to nurture my feminine side and teach me to be a proper young lady of the times. It didn't take. You can see by the expression on my face my heroic struggle to endure privation and torture for completely unfathomable reasons. Nothing has changed.

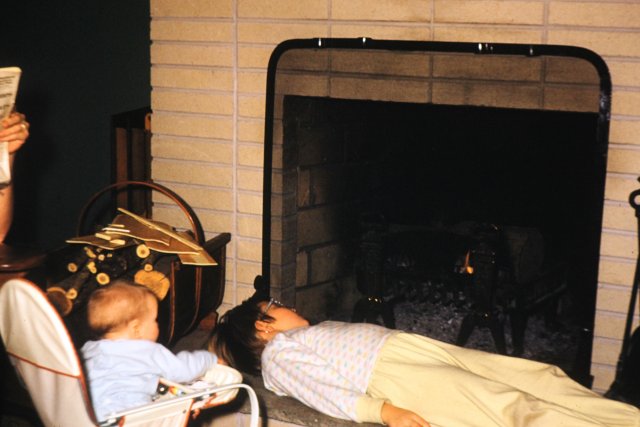

As a young mother, Thanksgiving at my in-laws' place in Moncks Corner, South Carolina, usually found me collapsed on the hearth in front of a comforting fire. This picture from Christmas at my grandparents' house in Rochester, New York shows that when I was seven I felt much the same way.

When this swing was new, it graced my grandfather's house. When he moved in with my family in Pennsylvania, the swing came with him. That particular swing is gone now, but when Porter found one for all practical purposes identical at our local Lowes, I had to have one for our Florida back porch. North or south, for more than 60 years I have found it one of the most comfortable places ever to sit, rock, read, think ... and sleep.

I don't mean we can't change. Nature vs. Nurture should no longer be a debate, since the answer is so clearly "both/and." But it still surprises me when I come across evidence—in myself and others—that many of our present characteristics were manifested very early on, if we'd had the eyes to see. Mostly it's fascinating; it only becomes depressing when I look back and realize I'm still fighting battles it seems I ought to have long since conquered and moved on.

So I wonder: Should we, as parents, be more alert to problems in our children that could lead to trouble in the future, and deal with them, rather than letting them slide and hoping they'll outgrow them? If so, which ones are manifestly bad and need eliminating (e.g. lying, laziness, disobedience), and which ones are just part of what makes us individuals (such as a need for solitude, a sensitive nature, or a very logical mind), in which case our job is to help the child both take advantage of the good and develop coping strategies for the bad?

Permalink | Read 1615 times | Comments (2)

Category Children & Family Issues: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Random Musings: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

Digital Minimalism: Choosing a Focused Life in a Noisy World by Cal Newport (Portfolio/Penguin 2019)

Digital Minimalism: Choosing a Focused Life in a Noisy World by Cal Newport (Portfolio/Penguin 2019)

Janet recommended this one to me, and after checking out Newport's TED talk, "Why You Should Quit Social Media," I decided to reserve it at the library. I had to wait in line; maybe more than a few people are rethinking Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, Old Uncle Tom Cobleigh and all.

Digital Minimalism is divided into two parts: Foundations, and Practices. I read through Foundations easily, able to enjoy the book without pasting sticky tabs all over it. For me, this is like going somewhere and not taking pictures. Those sticky notes represent text that I will later laboriously transcribe for my reviews. As with the photos, something is gained but something is lost. I was enjoying the book and anticipating an easy review.

Then I hit Practices. Or Practices hit me.

The first chapter of that section, "Spend Time Alone," is about solitude deprivation. I could have sticky-noted the whole chapter. Here is me, restraining myself:

Everyone benefits from regular doses of solitude, and, equally important, anyone who avoids this state for an extended period of time will ... suffer. ... Regardless of how you decide to shape your digital ecosystem, you should give your brain the regular doses of quiet it requires to support a monumental life. (pp. 91-92).

[Raymond] Kethledge is a respected judge serving on the United States Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit, and [Michael] Erwin is a former army officer who served in both Iraq and Afghanistan. ... [Their book on the topic of solitude], Lead Yourself First ... summarizes, with the tight logic you expect from a federal judge and former military officer, [their] case for the importance of being alone with your thoughts. Before outlining their case, however, the authors start with what is arguably one of their most valuable contributions, a precise definition of solitude. Many people mistakenly associate this term with physical separation—requiring, perhaps, that you hike to a remote cabin miles from another human being. This flawed definition introduces a standard of isolation that can be impractical for most to satisfy on any sort of a regular basis. As Kethledge and Erwin explain, however, solitude is about what’s happening in your brain, not the environment around you. Accordingly, they define it to be a subjective state in which your mind is free from input from other minds. (pp. 92-93)

You can enjoy solitude in a crowded coffee shop, on a subway car, or, as President Lincoln discovered at his cottage, while sharing your lawn with two companies of Union soldiers, so long as your mind is left to grapple only with its own thoughts. On the other hand, solitude can be banished in even the quietest setting if you allow input from other minds to intrude. In addition to direct conversation with another person, these inputs can also take the form of reading a book, listening to a podcast, watching TV, or performing just about any activity that might draw your attention to a smartphone screen. Solitude requires you to move past reacting to information created by other people and focus instead on your own thoughts and experiences—wherever you happen to be. (pp. 93-94).

Regular doses of solitude, mixed in with our default mode of sociality, are necessary to flourish as a human being. It’s more urgent now than ever that we recognize this fact, because ... for the first time in human history solitude is starting to fade away altogether. (p. 99)

The concern that modernity is at odds with solitude is not new. ... The question before us, then, is whether our current moment offers a new threat to solitude that is somehow more pressing than those that commentators have bemoaned for decades. ... To understand my concern, the right place to start is the iPod revolution that occurred in the first years of the twenty-first century. We had portable music before the iPod ... but these devices played only a restricted role in most people’s lives—something you used to entertain yourself while exercising, or in the back seat of a car on a long family road trip. If you stood on a busy city street corner in the early 1990s, you would not see too many people sporting black foam Sony earphones on their way to work. By the early 2000s, however, if you stood on that same street corner, white earbuds would be near ubiquitous. The iPod succeeded not just by selling lots of units, but also by changing the culture surrounding portable music. It became common, especially among younger generations, to allow your iPod to provide a musical backdrop to your entire day—putting the earbuds in as you walk out the door and taking them off only when you couldn’t avoid having to talk to another human. (pp. 99-100).

This transformation started by the iPod, however, didn’t reach its full potential until the release of its successor, the iPhone.... Even though iPods became ubiquitous, there were still moments in which it was either too much trouble to slip in the earbuds (think: waiting to be called into a meeting), or it might be socially awkward to do so (think: sitting bored during a slow hymn at a church service). The smartphone provided a new technique to banish these remaining slivers of solitude: the quick glance. (p. 101)

When you avoid solitude, you miss out on the positive things it brings you: the ability to clarify hard problems, to regulate your emotions, to build moral courage, and to strengthen relationships. (p. 104)

Eliminating solitude also introduces new negative repercussions that we’re only now beginning to understand. A good way to investigate a behavior’s effect is to study a population that pushes the behavior to an extreme. When it comes to constant connectivity, these extremes are readily apparent among young people born after 1995—the first group to enter their preteen years with access to smartphones, tablets, and persistent internet connectivity. ... If persistent solitude deprivation causes problems, we should see them show up here first. ...

The head of mental health services at a well-known university ... told me that she had begun seeing major shifts in student mental health. ... Seemingly overnight the number of students seeking mental health counseling massively expanded, and the standard mix of teenage issues was dominated by something that used to be relatively rare: anxiety. ... The sudden rise in anxiety-related problems coincided with the first incoming classes of students that were raised on smartphones and social media. She noticed that these new students were constantly and frantically processing and sending messages. ...

[San Diego State University psychology professor Jean Twenge observed that] young people born between 1995 and 2012 are ... on the brink of the worst mental-health crisis in decades. ... [She] made it clear that she didn’t set out to implicate the smartphone: “It seemed like too easy an explanation for negative mental-health outcomes in teens,” but it ended up the only explanation that fit the timing. Lots of potential culprits, from stressful current events to increased academic pressure, existed before the spike in anxiety.... The only factor that dramatically increased right around the same time as teenage anxiety was the number of young people owning their own smartphones. ...

When journalist Benoit Denizet-Lewis investigated this teen anxiety epidemic in the New York Times Magazine, he also discovered that the smartphone kept emerging as a persistent signal among the noise of plausible hypotheses. “Anxious kids certainly existed before Instagram,” he writes, “but many of the parents I spoke to worried that their kids’ digital habits—round-the-clock responding to texts, posting to social media, obsessively following the filtered exploits of peers—were partly to blame for their children’s struggles.” Denizet-Lewis assumed that the teenagers themselves would dismiss this theory as standard parental grumbling, but this is not what happened. “To my surprise, anxious teenagers tended to agree.” A college student he interviewed at a residential anxiety treatment center put it well: “Social media is a tool, but it’s become this thing that we can’t live without that’s making us crazy.” (pp. 104-107)

The pianist Glenn Gould once proposed a mathematical formula for this cycle, telling a journalist: “I’ve always had a sort of intuition that for every hour you spend with other human beings you need X number of hours alone. Now what that X represents I don’t really know . . . but it’s a substantial ratio.” (p. 111)

The past two decades ... are characterized by the rapid spread of digital communication tools—my name for apps, services, or sites that enable people to interact through digital networks—which have pushed people’s social networks to be much larger and much less local, while encouraging interactions through short, text-based messages and approval clicks that are orders of magnitude less information laden than what we have evolved to expect. ... Much in the same way that the “innovation” of highly processed foods in the mid-twentieth century led to a global health crisis, the unintended side effects of digital communication tools—a sort of social fast food—are proving to be similarly worrisome.(p. 136).

After winning me over with the chapter on solitude deprivation, Newport lost me somewhat with his approach to taming the beasts. The basic problem is that, for a guy who has written several books and has his own blog, he seems to have very little respect for the written word.

Many people think about conversation and connection as two different strategies for accomplishing the same goal of maintaining their social life. This mind-set believes that there are many different ways to tend important relationships in your life, and in our current modern moment, you should use all tools available—spanning from old-fashioned face-to-face talking, to tapping the heart icon on a friend’s Instagram post.

The philosophy of conversation-centric communication takes a harder stance. It argues that conversation is the only form of interaction that in some sense counts toward maintaining a relationship. This conversation can take the form of a face-to-face meeting, or it can be a video chat or a phone call—so long as it matches Sherry Turkle’s criteria of involving nuanced analog cues, such as the tone of your voice or facial expressions. Anything textual or non-interactive—basically, all social media, email, text, and instant messaging—doesn’t count as conversation and should instead be categorized as mere connection. (p. 147)

I heartily disagree with his lumping e-mail in with "all social media, text, and instant messaging." I will grant that most social media, texts, WhatsApp, IM, and the like are severely limited by the difficulty of creating the message. Phones simply are not designed for high-speed typing, and I don't know about other people's experiences, but for me voice-to-text makes so many errors I spend almost as much time correcting as I would have laboriously pecking out a message on the tiny keyboard. (That's why I much prefer WhatsApp, where I can type my messages on the computer keyboard, to texting, where I can't.) So messages tend to be short, of restricted vocabulary and complexity, and full of nasty abbreviations. But e-mails are simply typed letters that get delivered with much more speed than the mail can achieve. I will grant that you miss the tone-of-voice cues that can be heard over the phone, but I think that's often more than made up for by the ability to both speak and listen without interruption. On the phone, if I turn all my attention to what the other person is saying, there's a long silence when it's my turn to talk while I think of how I want to respond. But if I try to figure that out while the other person is speaking, I'm likely to miss, or mis-interpret what is said. And when I'm speaking, it's more than likely that I will get interrupted before getting out my entire thought, and the conversation will veer off in another direction, leaving my response incomplete and likely mis-understood. E-mail leaves plenty of time for listening, thinking, and responding.

Newport has serious problems with Facebook's "Like" button. I can see his point in some respects.

The “Like” feature evolved to become the foundation on which Facebook rebuilt itself from a fun amusement that people occasionally checked, to a digital slot machine that began to dominate its users’ time and attention. This button introduced a rich new stream of social approval indicators that arrive in an unpredictable fashion—creating an almost impossibly appealing impulse to keep checking your account. It also provided Facebook much more detailed information on your preferences, allowing their machine-learning algorithms to digest your humanity into statistical slivers that could then be mined to push you toward targeted ads and stickier content. (p. 192)

I do get the slot-machine analogy. We all crave (positive) feedback for whatever of ourselves we have put "out there." And the temptation to keep checking is real. It reminds me of the joke from 'way back in the America Online days, in which the person sitting at the computer (no smart phones back then) checks his mail, sees that there is none waiting for him—and immediately checks again. It was funny because that's what so many people did. But I think Newport misunderstands how many of us use the Like button.

In the context of this chapter, however, I don’t want to focus on the boon the “Like” button proved to be for social media companies. I want to instead focus on the harm it inflicted to our human need for real conversation. To click “Like,” within the precise definitions of information theory, is literally the least informative type of nontrivial communication, providing only a minimal one bit of information about the state of the sender (the person clicking the icon on a post) to the receiver (the person who published the post). Earlier, I cited extensive research that supports the claim that the human brain has evolved to process the flood of information generated by face-to-face interactions. To replace this rich flow with a single bit is the ultimate insult to our social processing machinery. (p. 153)

But here's the thing. I don't know anyone who pretends that clicking "Like" or "Love" or "I care" is conversation. However, it is the digital equivalent of one part of a successful conversation: the nod, the smile, the grunt, the frown, the short interjection, which in face-to-face conversation we used as an important lubricant to keep a conversation running smoothly. It hardly communicates any more information than the Facebook buttons; maybe it's little more than a bit—but it's an important bit. It says, "I'm listening, I hear you, I agree, keep talking," or "Wait, what you said confuses me, or angers me," or "I'm sorry, I sympathize."

As soon as easier communication technologies were introduced—text messages, emails—people seemed eager to abandon this time-tested method of conversation for lower-quality connections (Sherry Turkle calls this effect “phone phobia”). (p. 160)

Guilty as charged, but there's no need for Newport (or Turkle) to be snarky about it. I'm hardly alone, and there's ample evidence that phone phobia is attached to the same set of genes that makes me like mathematics. I love the (true) story a colleague told of a bunch of math grad students who decided to order pizza. Every one of them hemmed and hawed and delayed making the order, until the wife of one of the mathematicians, herself a grad student in philosophy, sighed, "For Pete's sake!" and called the restaurant. Text-based communication is a real boon to people like us. Call it a disability if you like—and then remember that you shouldn't mock or discriminate against people with disabilities.

Fortunately, there’s a simple practice that can help you sidestep these inconveniences and make it much easier to regularly enjoy rich phone conversations. I learned it from a technology executive in Silicon Valley who innovated a novel strategy for supporting high-quality interaction with friends and family: he tells them that he’s always available to talk on the phone at 5:30 p.m. on weekdays. There’s no need to schedule a conversation or let him know when you plan to call—just dial him up. As it turns out, 5:30 is when he begins his traffic-clogged commute home in the Bay Area. He decided at some point that he wanted to put this daily period of car confinement to good use, so he invented the 5:30 rule. The logistical simplicity of this system enables this executive to easily shift time-consuming, low-quality connections into higher-quality conversation. If you write him with a somewhat complicated question, he can reply, “I’d love to get into that. Call me at 5:30 any day you want.” Similarly, when I was visiting San Francisco a few years back and wanted to arrange a get-together, he replied that I could catch him on the phone any day at 5:30, and we could work out a plan. When he wants to catch up with someone he hasn’t spoken to in a while, he can send them a quick note saying, “I’d love to get up to speed on what’s going on in your life, call me at 5:30 sometime.” ... He hacked his schedule in such a way that eliminated most of the overhead related to conversation and therefore allowed him to easily serve his human need for rich interaction. (pp. 161-162)

I have to say, that strikes me as more selfish than clever. It's saying to everyone else that he will only communicate with them through his own preferred medium. Granted, it's his right to do so, and maybe he's learned that that's the best way he can get the most accomplished. But I'd have to be pretty desperate to call someone who I knew was going to be driving while he is talking with me. Either he's not going to be giving me his full attention, or he's not going to be giving the other cars on the road his full attention, neither one of which strikes me as ideal. And if I have a complicated question, I definitely want the response to be by written word, where there's a record of what was said, and more chance of getting a well thought out response.

I’ve seen several variations of this practice work well. Using a commute for phone conversations, like the executive introduced above, is a good idea if you follow a regular commuting schedule. It also transforms a potentially wasted part of your day into something meaningful. Coffee shop hours are also popular. In this variation, you pick some time each week during which you settle into a table at your favorite coffee shop with the newspaper or a good book. The reading, however, is just the backup activity. You spread the word among people you know that you’re always at the shop during these hours with the hope that you soon cultivate a rotating group of regulars that come hang out. ... You can also consider running these office hours once a week during happy hour at a favored bar. (pp. 162-163)

<Shudder> Really? I'm supposed to go to the expense, inconvenience, and annoyance of sitting around at a coffee shop or bar on spec, just hoping a friend shows up? And expect my friends to be willing to pay an insane amount for a cup of coffee just to talk with me? Here, and in many other places in Digital Minimalism, you can tell that Newport is an extrovert—with plenty of spare cash—and friends who are the same.

And anyway, whatever happened to visiting people in their homes? One friend of ours decided to quit Facebook, and in her final message invited anyone in town to drop by her house for tea. I could get into that. If you're willing to get out and drive to a restaurant, come instead and knock at our door. You'll be more than welcome and none one of us will have to buy an expensive drink. (This pandemic won't last forever.)

[In the early 20th century, Arnold Bennett, author of How to Live on 24 Hours a Day, speaking of leisure activities] argues that these hours should instead be put to use for demanding and virtuous leisure activities. Bennett, being an early twentieth-century British snob, suggests activities that center on reading difficult literature and rigorous self-reflection. In a representative passage, Bennett dismisses novels because they “never demand any appreciable mental application.” A good leisure pursuit, in Bennett’s calculus, should require more “mental strain” to enjoy (he recommends difficult poetry). (p. 175)

Newport approves of the idea that "the value you receive from a pursuit is often proportional to the energy invested." But then he adds,

For our twenty-first-century purposes, we can ignore the specific activities Bennett suggests. (p. 175)

And what, pray tell, is snobbish or unreasonable about literature and poetry?

Newport has a lot to say about the value of craft: of woodworking, or renovating a bathroom, or repairing a motorcycle, or knitting a sweater. He includes musical performances as well. But—and I find this odd for an author—he seems to have little respect for creating books. Would it be a more noble activity if they were typed on an old Remington, or handwritten? He similarly discounts composing music using a computer as less worthwhile than playing a guitar. I don't buy it.

The following story is for our two oldest grandsons, who have a way of picking up and enjoying construction skills.

[Pete's] welding odyssey began in 2005. At the time, he was building a custom home. ... The house was modern so Pete integrated some custom metalwork into his design plan, including a beautiful custom steel railing on the stairs.

The design seemed like a great idea until Pete received a quote from his metal contractor for the work: it was for $15,800, and Pete had budgeted only $4,000. “If this guy is billing out his metalworking time at $75.00 an hour, that’s a sign that I need to finally learn the craft myself,” Pete recalls thinking at the time. “How hard can it be?” In Pete’s hands, the answer turned out to be: not that hard.

Pete bought a grinder, a metal chop saw, a visor, heavy-duty gloves, and a 120-volt wire-feed flux core welder—which, as Pete explains, is by far the easiest welding device to learn. He then picked some simple projects, loaded up some YouTube videos, and got to work. Before long, Pete became a competent welder—not a master craftsman, but skilled enough to save himself tens of thousands of dollars in labor and parts. (As Pete explains it, he can’t craft a “curvaceous supercar,” but he could certainly weld up a “nice Mad-Max-style dune buggy.”) In addition to completing the railing for his custom home project (for much less than the $15,800 he was quoted), Pete went on to build a similar railing for a rooftop patio on a nearby home. He then started creating steel garden gates and unusual plant holders. He built a custom lumber rack for his pickup truck and fabricated a series of structural parts for straightening up old foundations and floors in the historic homes in his neighborhood. As Pete was writing his post on welding, a metal attachment bracket for his garage door opener broke. He easily fixed it. (pp. 194-195)

If you're wondering where to learn skills needed for simple projects ... the answer is easy. Almost every modern-day handyperson I've spoken to recommends the exact same source for quick how-to lessons: YouTube. (pp. 197-198, emphasis mine)

In the middle of a busy workday, or after a particularly trying morning of childcare, it’s tempting to crave the release of having nothing to do—whole blocks of time with no schedule, no expectations, and no activity beyond whatever seems to catch your attention in the moment. These decompression sessions have their place, but their rewards are muted, as they tend to devolve toward low-quality activities like mindless phone swiping and half-hearted binge-watching. ... Investing energy into something hard but worthwhile almost always returns much richer rewards. (p. 212)

Finally, I can't resist his description of former Kickstarter project called the Light Phone.

Here’s how it works. Let’s say you have a Light Phone, which is an elegant slab of white plastic about the size of two or three stacked credit cards. This phone has a keypad and a small number display. And that’s it. All it can do is receive and make telephone calls—about as far as you can get from a modern smartphone while still technically counting as a communication device.

Assume you’re leaving the house to run some errands, and you want freedom from constant attacks on your attention. You activate your Light Phone through a few taps on your normal smartphone. At this point, any calls to your normal phone number will be forwarded to your Light Phone. If you call someone from it, the call will show up as coming from your normal smartphone number as well. When you’re ready to put the Light Phone away, a few more taps turns off the forwarding. This is not a replacement for your smartphone, but instead an escape hatch that allows you to take long breaks from it. (p. 245).

Despite our areas of disagreement, there's only one really, really annoying section of the book. He spends seven pages on the ideas of someone named Jennifer who "prefers the pronoun 'they/their' to 'she/her'." The ideas are not worth the ensuing confusion between singular and plural. I found myself constantly re-reading trying to figure out who was being referenced in the text.

But I do recommend reading Digital Minimalism. The concept of solitude deprivation alone would make it worthwhile, and the rest of the book is pretty good, too—especially if you're not a phone-phobic, introverted author.

Permalink | Read 2276 times | Comments (6)

Category Reviews: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Education: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Health: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Computing: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Children & Family Issues: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Social Media: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

This post is about 40 years late in coming. But I'm reading Cal Newport's Digital Minimalism, and was struck by something right at the beginning.

Newport reports that Bill Maher—some television personality I'd never heard of, but that's not the point—had a show in which he likened the deliberately-engineered addictiveness of social media to the deliberately-engineered addictiveness of tobacco. "Philip Morris just wanted your lungs," he concluded. "The App Store wants your soul." It could be argued that what both really want is your money, and I don't think Maher would disagree.

Back to Sesame Street. Maher could have looked a little further and realized that the whole television industry is just as guilty of enticing us to mainline its products. I pick on Sesame Street largely because it was so strongly sold as something good for children, and the pushers were not just the networks but teachers and doctors and social workers and neighbors.

Yet the show was filled with all the techniques that promote addiction, shorten attention spans, and actually change our brains, such as bright colors, fast, catchy music, and rapid-fire changes of focus. And when you think about it, what exactly was educational about the show? What did it teach?

Letters and numbers? Nothing that spending that time with parents and siblings couldn't have taught faster and better.

What it did teach effectively was a certain kind of socialization. Sesame Street was a neighborhood, and those who produced the show had very definite ideas about what makes a good neighborhood and how neighbors should behave. (Note that these ideas sometimes changed over time, with videos of the older shows now labelled "for adults only," because they show children riding bikes without helmets and walking to the store unaccompanied by an adult.)

If your family's own values happen to coincide with those of the show's creators, well and good. If you happen to think a complete stranger can do a better job of helping your child learn to deal with anger, grief, fear, death, divorce, illness, disability, and even love than you can, well, there you go.

But if you disagree, know that Sesame Street is a very effective propaganda machine that is teaching a whole lot more than the alphabet. Even Mister Rogers' Neighborhood, which I considered to be a far superior show, couldn't resist trying to act in loco parentis on personal and social issues. What goes on in today's children's shows I don't have the need (or stomach) to investigate.

How is it that we parents have become so timid and unsure of ourselves that we're eager to turn much of our children's character formation over to others?

Permalink | Read 1517 times | Comments (0)

Category Children & Family Issues: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

Recently I stumbled upon The Conservative Student's Survival Guide. It's a five-minute video offering advice to—you guessed it—conservative students who find themselves a despised minority on liberal college campuses. That's no joke: for all the talk you'll hear from academia about tolerance, liberal values, and minority rights, it's a jungle out there if your particular minority isn't currently in favor, and it seems the only status more dangerous than "conservative student" on most American campuses is "conservative faculty." It was true when we were in college, it was true when our children were in college—and everything I see leads me to believe the situation is far, far worse now.

What's surprising about this video is that, unlike much that comes from both Left and Right these days, it is calm, well-reasoned, and respectful. What's more, even though it's aimed at conservative students, any thoughtful person who wants to make the most of his college experience would do well to consider this advice.

The speaker is Matthew Woessner, a Penn State political science professor. All of his seven suggestions make sense, but my top three are these:

- Avoid pointless ideological battles. It's not your job to convert your professors or your fellow students. Discuss and debate, but don't push too hard.

- Choose [your classes and your major] wisely. I was a liberal atheist in college, but much on campus was too far Left even for me. Being a student of the hard sciences saved me from a great deal of the insanity that was going on in the humanities and social sciences departments. A quarter-century later, one of our daughters found some of the same relief as an engineering major. Our other daughter, however, discovered that life at a music conservatory was quite difficult—despite the name, conservative values were not welcome.

- Work hard—college faculty value hard-working, enthusiastic students. I'd say this is the most valuable of all his points. Excellence and enthusiasm are attractive. A student who participates respectfully in class, does the work, and learns the material will gain the respect and appreciation of most of his professors. Teachers are like that.

C. S. Lewis wrote the Preface to a book by B. G. Sandhurst entitled How Heathen is Britain? This essay has been republished as the thirteenth chapter of Lewis's book, God in the Dock, which I recently finished re-reading. I deemed the excerpts below too extensive for my review of that book, so here they are in their own post.

The essay, written in the mid-1940's, deals largely with the effect of state education on students' beliefs and attitudes about the Christian faith. A few quotes can't do justice to the logic of the argument, but should suffice to give the flavor. All bold emphasis is my own.

The content of, and the case for, Christianity, are not put before most schoolboys under the present system; ... when they are so put a majority find them acceptable. ... [These two facts] blow away a whole fog of "reasons for the decline of religion" which are often advanced and often believed. If we had noticed that the young men of the present day found it harder and harder to get the right answers to sums, we should consider that this had been adequately explained the moment we discovered that schools had for some years ceased to teach arithmetic. (p. 115)

The sources of unbelief among young people today do not lie in those young people. The outlook which they have—until they are taught better—is a backwash from an earlier period. It is nothing intrinsic to themselves which holds them back from the Faith. This very obvious fact—that each generation is taught by an earlier generation—must be kept very firmly in mind. (p. 116)

No generation can bequeath to its successor what it has not got. You may frame the syllabus as you please. But when you have planned and reported ad nauseam, if we are skeptical we shall teach only skepticism to our pupils, if fools only folly, if vulgar only vulgarity, if saints sanctity, if heroes heroism. ... Nothing which was not in the teachers can flow from them into the pupils. (p. 116)

A society which is predominantly Christian will propagate Christianity through its schools: one which is not, will not. All the ministries of education in the world cannot alter this law. We have, in the long run, little either to hope or fear from government.

The State may take education more and more firmly under its wing. I do not doubt that by so doing it can foster conformity, perhaps even servility, up to a point; the power of the State to deliberalize a profession is undoubtedly very great. But all the teaching must still be done by concrete human individuals. The State has to use the men who exist. Nay, as long as we remain a democracy, it is men who give the State its powers. And over these men, until all freedom is extinguished, the free winds of opinion blow. Their minds are formed by influences which government cannot control. And as they come to be, so will they teach. ... Let the abstract scheme of education be what it will: its actual operation will be what the men make it. ... Your "reform" may incommode and overwork them, but it will not radically alter the total effect of their teaching. (pp. 116-117)

Where the tide flows towards increasing State control, Christianity, with its claims in one way personal and in the other way ecumenical and both ways antithetical to omnicompetent government, must always in fact (though not for a long time yet in words) be treated as an enemy. Like learning, like the family, like any ancient and liberal profession, like the common law, it gives the individual a standing ground against the State. Hence Rousseau, the father of the totalitarians, said wisely enough, from his own point of view, of Christianity, Je ne connais rien de plus contraire à l'esprit social ("I know nothing more opposed to the social spirit"). ... Even if we were permitted to force a Christian curriculum on the existing schools with the existing teachers we should only be making masters hypocrites and hardening thereby the pupils' hearts. (p. 118)

I am speaking, of course, of large schools on which a secular character is already stamped. If any man, in some little corner out of the reach of the omnicompetent, can make, or preserve a really Christian school, that is another matter. His duty is plain. (p. 119)

What a society has, that, be sure, and nothing else, it will hand on to its young. The work is urgent, for men perish around us. But there is no need to be uneasy about the ultimate event. As long as Christians have children and non-Christians do not, one need have no anxiety for the next century. (p. 119)

Clearly Lewis did not anticipate that Christians would embrace the radical move to very small families nearly as much as secular society did. I'm thankful for those who are now reversing that trend. The idea is mocked today ("evangelism by procreation"), but Lewis—though he had a difficult home life and no biological children of his own—clearly recognized the life- and faith-affirming value of begetting and bearing children in Christian families.

As for the rest of the quotations: it is still true that democratic governments have much less control over what children think and learn than they would like. But the same is now also true of teachers. Lewis was thinking of the influence of teachers when he wrote,

Planning has no magic whereby it can elicit figs from thistles or choke-pears from vines. The rich, sappy, fruit-laden tree will bear sweetness and strength and spiritual health; the dry, prickly, withered tree will teach hate, jealousy, suspicion, and inferiority ... [no matter what] you tell it to teach. (pp. 117-118)

This is even more true, now, of the movies, music, and other media that are the very air our young people breathe (and rarely think about), and of the peer-oriented society we have bequeathed them. As I wrote in my review of Gordon Neufeld and Gabor Maté's book Hold On to Your Kids (a book I strongly recommend to all parents, grandparents, teachers, pastors, and anyone else who cares about children),

It is essential to the survival of a civilization that its culture be passed on from one generation to another. Today's children are not receiving culture, they are inventing it as they go along. We are into the third generation of this problem, and appear to be reaching a tipping point. If the idea of peer culture being more important to children than their family culture doesn't seem strange and wrong to us, it's because that's how we grew up, too.