When our kids were in school, individual learning styles were becoming a big thing. They were each given a test that supposedly categorized them as Visual, Auditory, or Kinesthetic learners. We could see some truth in the results, though the skeptic in me wasn't sure it had any more basis in reality than finding some truth in the Chinese Zodiac descriptions you see on the placemats in cheap Chinese restaurants.

Here's a presentation that agrees with my cynical view (15 minutes):

The contrast between the enormous popularity of the learning styles approach within education, and the lack of credible evidence for its utility is, in our opinion, striking and disturbing.

There's a large body of literature that supports the claim that everyone learns better with multi-modal approaches, where words and pictures are presented together, rather than either words or pictures alone.

Ultimately, the most important thing for learning is not the way the information is presented, but what is happening inside the learner's head. People learn best when they're actively thinking about the material, solving problems, or imagining what happens if different variables change.

I call this just another bit of evidence for the harm we do when we label people. You're a kinesthetic learner, she has ADHD, he's "on the spectrum," I suffer from face blindness.... Sometimes labels can help us understand ourselves better, but more often they encourage us (and our parents, teachers, employers) to shut ourselves up in boxes and put limits on our abilities.

My constant prayer during Pandemic-tide has been that we would learn to think outside our traditional, largely unquestioned, boxes of life. And so we have.

Many more workers—and their employers—have discovered that remote work can be a good thing. This is not new; back in the day we called it "telecommuting" and it came with both blessings (work from anywhere at any time) and curses (work from everywhere all the time). But, thanks to the pandemic restrictions, the number of people exercising this option has grown to where it's having a significant effect on the demographics of the country. Just ask the citizens of New Hampshire, whose real estate prices have been driven through the roof by pressure from Boston- and New York City-dwellers who no longer need to live in an expensive city to work there. Again: blessings and curses.

More exciting to me is the surge in home education.

A friend sent me this Associated Press article from mid-April, confirming what I've been hearing elsewhere: Homeschooling Surge Continues Despite Schools Reopening.

The coronavirus pandemic ushered in what may be the most rapid rise in homeschooling the U.S. has ever seen. Two years later, even after schools reopened and vaccines became widely available, many parents have chosen to continue directing their children’s educations themselves.

Families that may have turned to homeschooling as an alternative to hastily assembled remote learning plans have stuck with it—reasons include health concerns, disagreement with school policies and a desire to keep what has worked for their children.

[A Buffalo, New York mother] says her children are never going back to traditional school. Unimpressed with the lessons offered remotely when schools abruptly closed their doors in spring 2020, she began homeschooling her then fifth- and seventh-grade children that fall. [She] had been working as a teacher’s aide [and] knew she could do better herself. She said her children have thrived with lessons tailored to their interests, learning styles and schedules.

Once a relatively rare practice chosen most often for reasons related to instruction on religion, homeschooling grew rapidly in popularity following the turn of the century before [it] leveled off at around 3.3%, or about 2 million students, in the years before the pandemic, according to the Census. Surveys have indicated factors including dissatisfaction with neighborhood schools, concerns about school environment and the appeal of customizing an education.

As usual, even a good article gets some things wrong. Home education is no new phenomenon, but as old as the hills. Abraham Lincoln was just one of many homeschooled presidents, though in those days they called it "self-educated." And for a very long time it had nothing in particular to do with reasons of religion. Children were home-educated by necessity (schools unavailable, or children needed at home, e.g. Lincoln), because of an intellectual mismatch between child and school (e.g. Thomas Edison, Albert Einstein), because the atmosphere and philosophies of the schools differed significantly from those of the parents (sometimes associated with a particular religion, sometimes not), or simply because parents and/or children were dissatisfied with what the schools had to offer. In the last quarter of the 20th century, it is true, homeschooling ranks were swelled by Evangelical Christians who had discovered that the Amish were right: home education could meet their needs better than public or even Christian schools. This raised the public's awareness of an educational phenomenon whose adherents had mostly been trying to fly under the radar, and led to home education's establishment as a valid and legal educational approach—at least in the United States. This new familiarity—nearly everyone now knew a homeschooling family—opened the field to many others, with varied reasons for their choices.

The proportion of Black families homeschooling their children increased by five times, from 3.3% to 16.1%, from spring 2020 to the fall, while the proportion about doubled across other groups. [emphasis mine] ...

“I think a lot of Black families realized that when we had to go to remote learning, they realized exactly what was being taught. And a lot of that doesn’t involve us,” said [a mother from Raleigh, North Carolina], who decided to homeschool her 7-, 10- and 11-year-old children. “My kids have a lot of questions about different things. I’m like, ‘Didn’t you learn that in school?’ They’re like, ‘No.’”

[The mother from Buffalo] said it was a combination of everything, with the pandemic compounding the misgivings she had already held about the public school system, including her philosophical differences over the need for vaccine and mask mandates and academic priorities. The pandemic, she said, “was kind of—they say the straw that broke the camel’s back—but the camel’s back was probably already broken.”

I find it especially exciting that minorities are discovering that they are not locked by their circumstances into an educational system that is not meeting their needs. The pandemic restrictions have given families of all descriptions the opportunity to taste educational freedom*, and many, having made that leap unwillingly, have chosen to stick with it.

Choice is the thing. If the great relief expressed by many parents at the re-opening of schools is any indication, I'd say that home education is unlikely to become a majority educational philosophy in America. But it works so well for so many families, including those who opt for different educational choices at different times in their lives—we ourselves made use of public, private, and home education at one time or another—that I'm thrilled to see homeschooling on the rise all over the country, and even the world.

Our established educational system is understandably threatened by any challenge to its power. (Nonetheless, we had many teachers who cheered on our own homeschooling efforts.) But powerful monopolies—in education as well as government, medicine, transportation, information, and all other essential services—are dangerous, even to themselves. Healthy competition can only make our public education better.

One new homeschooling mother summed it up well:

It’s just a whole new world that is a much better world for us.

*I realize that many homeschoolers are cringing at the idea that the at-home learning offered by schools (public and private) during the pandemic bore any resemblance to the true freedom of home education, since it usually attempted to replicate as much as possible the restrictions inherent in formal, mass instruction. Nonetheless, it opened eyes ... and doors.

The Virus and the Vaccine is a cautionary tale about the hasty development and widespread, rapid distribution of a vaccine against a devastating virus, created using a brand-new technology. It's a fascinating and frightening story, and my review is here.

I posted that review in 2005; the story has nothing to do with COVID-19.

The virus was poliovirus, and the vaccine was the Inactivated Poliovirus Vaccine, developed by Jonas Salk. The new technology was growing the polio virus in cultures made from ground-up monkey kidneys, instead of the traditional time-consuming process of using living monkeys. This sped up the research enormously and made the rapid development of the vaccine possible.

Polio was in the midst of a tremendous surge at the time, and parents welcomed a vaccine against the terrifying disease, which killed and paralyzed and particularly targeted children.

But there was a time-bomb hidden in the vaccine: SV-40, a monkey virus that survived inadequate purification procedures to contaminate nearly every dose of polio vaccine between 1954 and 1963, affecting about a hundred million people in the United States alone. (I was undoubtedly one of them.) Even after the contamination was discovered, the dangers were downplayed—contaminated batches were not recalled, but continued to be used—because it was widely accepted that the monkey virus, being from a different species, would do no harm.

Unfortunately, that proved to be a false and costly assumption. SV-40 is now known to be carcinogenic, and since the mid-1990’s has been discovered in many formerly rare brain and bone cancers, as well as lymphomas and leukemias. Is this a cause and effect connection, or a coincidence? The government and medical authorities are still downplaying the issue, because it does not concern the present-day polio vaccine. But even though the Centers for Disease control say in one place on their website that there is no connection, research reported on another page flatly contradicts that.

Does it matter now? SV-40 is no longer contaminating the polio vaccine. As calamitous as these cancers are, when weighed against the devastation caused by the polio virus itself, it is a reasonable post-facto conclusion that the benefits of continuing to administer the contaminated vaccine outweighed the risks.

What does matter is that the authorities of the time were wrong about the science, and knowingly exposed over half the population of the United States to the contaminated vaccine.

Polio was such a devastating and commonplace childhood disease that parents willingly, nay eagerly, accepted the assurances of the authorities and authorized the vaccine for their children.

Back in 2005, I ended my review of The Virus and the Vaccine with a pro-vaccination message, which I still believe today. But my confidence in the governmental and medical authorities is now at an all-time low, and Big Tech has joined that list. Our vaccine production may be safer today—though maybe not, given that many vaccines are produced in China—but it's abundantly clear that we still get the science wrong, we still suppress information, and we still interfere unreasonably in the medical decisions of others.

When I was very young, my mother used to make apricot-pineapple conserve. I have the recipe; it's simple, just dried apricots, crushed pineapple, and sugar. The tricky part is that the mixture, while cooking, bubbles and spits and must be stirred constantly. My father made a long, L-shaped wooded paddle so she could stir from beyond the surprisingly-long range of the very hot mixture. When my mother made conserve, it was an event.

Which may be why I've only tried the recipe once or twice. That, coupled with the fact that Porter doesn't care much for apricots and even less for pineapple, so other jams take much higher priority around here.

But I miss it, and am always eager to try it out when I find a jar in the grocery store. But those occasions are rare.

Then I got smart.

There, at our local Publix, was the solution. Well, not the ideal solution, but a great deal easier than making my own. Mixed together, the flavor is just about as I remember it, though the texture is a bit thicker. One of these days I still plan to make it from scratch, even though I lack my mom's amazing paddle. But in the meantime, this provides an awesome gustatory memory.

Milestone note: This is my 3000th blog post. That calls for something serious, but not depressing. Here you go:

Fairy tales ... are not responsible for producing in children fear, or any of the shapes of fear; fairy tales do not give the child the idea of the evil or the ugly; that is in the child already, because it is in the world already. Fairy tales do not give the child his first idea of bogey. What fairy tales give the child is his first clear idea of the possible defeat of bogey. The baby has known the dragon intimately ever since he had an imagination. What the fairy tale provides for him is a St. George to kill the dragon. — G. K. Chesterton, 1909 ("The Red Angel")

Since it is so likely that [children] will meet cruel enemies, let them at least have heard of brave knights and heroic courage. ... Let there be wicked kings and beheadings, battles and dungeons, giants and dragons, and let the villains be soundly killed at the end of the book. — C. S. Lewis, 1952 ("On Three Ways of Writing for Children")

I write stories for courageous kids who know that dragons are real, that they are evil, and that they must be defeated. I don’t do that because I want to hurt children, but because children do and will face hurts every day. I don’t want to expose them to evil, I want to help them become people for whom evil is an enemy to be exposed. I want to tell them dangerous stories so that they themselves will become dangerous—dangerous to the darkness. — S. D. Smith, 2022 ("My Blood for Yours")

Smith's essay in video form (three minutes).

P.S. There's a new Green Ember book to be released soon, Prince Lander and the Dragon War. Time to reread the previous books in preparation!

Our Culture of Fear could be the title of a post on the last two pandemic years, but not this time. As much as COVID hysteria has scarred our children, school hysteria may be even worse. What have we done to the psyches of this captive, vulnerable population?

Yesterday our local high school students experienced a "Code Red lockdown." Why? Because some students reported the presence on campus of an "unidentified adult."

Word of caution: Very little information has been forthcoming from any news reports I have been able to access, so it's likely that there are factors I know nothing about. However, had the person been carrying a weapon or been in any other way particularly dangerous, I'm sure it would not only have been in the news, but in the headlines.

Here's an e-mail that was sent out to parents, redacted to protect the guilty. (Click to enlarge)

I know this school. Our children attended there, and we put in thousands of hours of volunteer time. There are over 2500 students on a very large campus. How anyone could have picked out an "unidentified adult" is beyond me. When I was there, more than 90% of the students and most of the teachers could not have identified me. I would park my car, walk into the school, wave to the teachers, say hi to the students, and get on with my work. No fuss, no guards, no need to sign in, just a friendly neighbor welcomed into the school community.

How things have changed! If I were to do that today, apparently I would be detained, searched, and taken into custody.

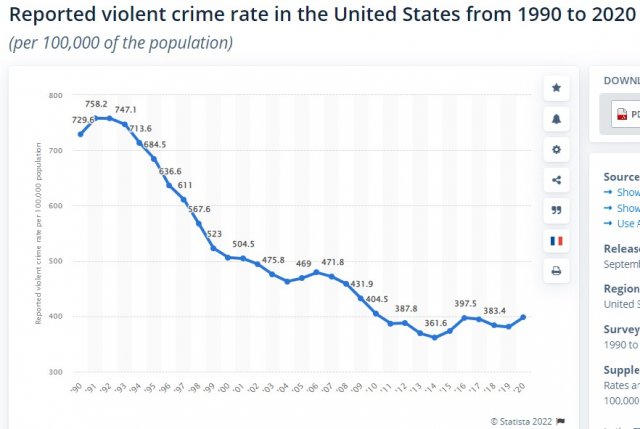

Before you lecture me that "It's not the 90's anymore; life is much more dangerous now," remember that the 90's were the peak of violent crime in the last half century. You can see that in this graph, from statista.com. (Click to enlarge)

Crime is 'way down, and fear is 'way up. School parents have reported that their children were absolutely terrified. I'm not sure I wouldn't have been myself, because a "lockdown" is a "lock in" and students can't get out. I'm not fond of being trapped, particularly when I have no idea that there isn't something really terrible going on.

Just as in our present pandemic situation, we are not paying nearly enough attention to the relative danger posed by extremely rare events that endanger children, and the damage a culture of fear does to their mental health.

The line between truth-telling and fear-mongering may be thinner than I'd like to believe.

I legitimately criticize most popular media outlets and others whose profits are driven by making people upset and afraid: I haven't seen such irresponsible journalism since the late 60's and early 70's. And yet I repeatedly write and share posts that I myself find frightening, because I think they highlight important information. If fear and panic are unhelpful, so are ignorance and denial. So I'll continue to publish information that I believe needs to be more widely known, trying not to be incendiary about it.

David Freiheit, my favorite Canadian lawyer/journalist, has given me gold mines of information about the legal aspects of current events. When I first began listening to his Viva Frei YouTube shows, one of the things that attracted me to him was his calm, balanced approach to events. I miss that. Now, after two years of pandemic stress, he's a bit edgier and angrier. But who can blame him? He lives in Montreal, where the provincial and federal governments continue to make unreasonable, unscientific, and inhumane intrusions into the lives of its people—far worse than anything we have had to endure. So please be patient with his anxiety; what he says is almost always eye-opening.

Below is a short clip from the full show that I will embed further on. This clip is only a minute and a half long, and if you don't find frightening both this use of children for propaganda purposes and what the children say with such enthusiasm, perhaps a study of 20th century history is in order. Or a reading of Orwell's Nineteen Eighty-Four. Or a chat with someone who fled to the United States from a totalitarian country.

Here's the full video (12.5 minutes) of which the story of the children is just a sidebar. I've been referring to Florida as a "free state" given what I consider to be our relatively reasonable response to the pandemic, but this Miami judge proves that we are hardly monolithic in our actions and opinions. Note that the issue is not so much the judge's desire to insist that all potential jurors be vaccinated, nor even his insulting, demeaning, and incendiary language, but a legal problem: "These judges are rendering decisions based on evidence that has not been adduced and that is not how the court system works."

In case you don't watch the video but are curious about the "insulting, demeaning, and incendiary language," this is what the judge wrote in his ruling, which was on the face of it a simple postponement of a trial because the defense counsel did not want the jury pool limited by vaccination status.

It is the Court's belief that the vast majority of the unvaccinated adults are uninformed and irrational, or—less charitably—selfish and unpatriotic.

Even if you completely agree with the judge, the children, and the teacher, these stories should send shivers down your spine.

Grace Victoria Daley

Born Sunday, October 24, 2021, 12:25 p.m.

Weight: 9 pounds, 9 ounces

Length: 20.5 inches

Mom, baby, and the whole family are doing well and are rejoicing with exceeding great joy over this delightful gift from God.

American Journeys Volume 1 by Lois Lenski (includes Indian Captive, Judy’s Journey, Flood Friday, Texas Tomboy, Boom Town Boy, Coal Camp Girl, and Mama Hattie’s Girl)

American Journeys Volume 2 by Lois Lenski (includes Strawberry Girl, Prairie School, Bayou Suzette, Blue Ridge Billy, Corn-Farm Boy, San Francisco Boy, and To Be a Logger)

Lois Lenski's children's books are a true treasure that all too few children—and parents and teachers—have discovered. I loved Indian Captive as a child, but didn't discover Strawberry Girl until I was an adult. Ocean-Born Mary came later still. Lenski's other books should not be so hard to find in our libraries! I discovered the fourteen above thanks to a sale on the Kindle versions of these collections, and what a treat they are! There are four other books in Lenski's American Regional series: Houseboat Girl (also available on Kindle), Cotton in My Sack, Deer Valley Girl, and Shoo-Fly Girl. Sadly, the last three are not available on Kindle.

These books are a much-needed antidote to what I call a chronological snobbery approach to teaching history. The term "chronological snobbery" isn't mine; I learned it from C. S. Lewis. All too often we look at the people and events of the past through ignorant, prideful eyes, as we are very good at seeing the areas in which we consider ourselves to be superior to our forebears, and very bad at even considering that there might be areas in which our forebears would justifiably consider us vastly inferior to themselves.

Lenski's books do an excellent job of avoiding that, for at least two reasons: they were largely written contemporaneously with the events they describe, and Lenski's research was meticulous and personal. She made a point of living in the situations she wrote about, getting to know the families, the work, and especially the children. For books where that was impossible, like Indian Captive and Ocean-Born Mary, she substituted thorough research and a heart sympathetic to all cultures.

Modern Americans may well be shocked by some of the situations in these books, but it is good for us to realize that our ways aren't the only ways that make for happy families and a healthy upbringing. Not to mention that other cultures may have done some things better than us. Nearly all the children in these books, for example, have many more responsibilities and at the same time much more freedom at younger ages than most modern parents can imagine.

The inspiration to write a review at this particular time? Amazon Kindle is currently (9/25/21) offering the second volume of these books for $3.99. Volume 1 is $31.99, so don't even think of buying it at that price. In my experience, with patience you will see it for $3.99 as well, and the individual books at $1.99. I highly recommend using (and supporting) a service called eReaderIQ, which will alert you when books or authors you are interested in go on sale.

I was pleased to see the following display at our local Publix. It's certainly a healthier alternative to the cookies that are usually offered to children at grocery stores.

Then I thought a bit about it. It may be a healthier treat, but there's one thing missing: it's just a bin of fruit; there is no human interaction.

Years ago, when our kids went to the bakery to receive their much-anticipated free cookies, it was a social event. The interaction with the "cookie lady"—the smiles, the brief exchange of words, the opportunity to practice basic courtesies such as saying "thank you"—was a small but significant part of their social education. Reaching into a bin is impersonal.

Something is gained, but something is lost.

Many years ago our Swiss relatives marvelled at how much of American society is not automated. Switzerland automates where it can—in paying tolls and parking fees, for example—because labor costs are so high there. It is good to have work in Switzerland, because jobs pay well and workers are respected. But of course in consequence there are fewer jobs and they require higher levels of training.

Like it or not, the move toward automation is accelerating in America, spurred on by our response to the pandemic and the consequent labor shortage. This is not necessarily a bad thing, but there's no doubt that whenever we make a purchase online, choose a self-checkout line at the grocery store, take a course online instead of in person, listen to a sermon or watch a service online instead of attending a local church, or watch a movie at home instead of in a theater, we are giving up an opportunity for meaningful interaction with others.

I'm a cast-iron introvert, and my first reaction is, "So what?" The less personal option is usually more efficient, more convenient, and avoids the risk of having to deal with rude sales clerks and cranky classmates. Automation and online opportunities open up a huge world of information, possibilities, and choice.

The danger is that they can close off another world: the messy world of having to control our nastier impulses and deal with the personalities, cultures, viewpoints, and yes, nastier impulses of other people; the beautiful world of personal encounters that force us to see the humanity of those whom we might be tempted to hate if our encounter were in an online political forum instead of a line at Home Depot.

It would make a somewhat confusing hand-me-down, but I think this is a great t-shirt. You can see where a black cloth marker has been used for updates.

Permalink | Read 773 times | Comments (0)

Category Children & Family Issues: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Just for Fun: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

It was our eight-year-old grandson's first solo sail. He had passed all his dad's tests the day before, and was eager to go solo, despite the strong wind and tide, which were at least pushing him into the cove, rather than out into Long Island Sound. So off he went.

It was, indeed, a strong wind, which made the small boat difficult to control. He capsized twice, gamely righting the boat and climbing back in each time. After a while, however, his lack of ability to make progress toward home began to frustrate and frighten him. I would not have handled that situation at all well.

Instead of giving in to panic, however, he assessed the situation, and discovered a patch of reeds he could head for with full assistance of the wind and tide. That's where he went, planning to pull the boat up on land and walk back to the cottage for help. He grounded in the reeds, lowered the sail, removed the daggerboard and rudder, and began pulling the boat up onto the land.

He didn't quite get the chance to finish. Watching from the shore, determined not to interfere with his very own adventure, but ready to render assistance as needed, we finally decided that a "rescue party" might be of some use. When they arrived (by land) he had already done all that was necessary except for securing the boat. Mission (nearly) accomplished, both boy and boat safe and sound—then, and only then, did he give in to tears.

Kudos to the security guard who had stopped by to see what was going on: he could have said so many wrong things, but merely commended the boy for his courage and clear head, telling him he had done exactly the right things.

It was a much more satisfactory reaction than that of my own sailing adventure six years earlier: the panicked onlooker who called 911, the fire boat officials who told me they were under orders to "take me in," and the ambulance crew persistently ready to pounce on me as soon as I set foot on shore (but I outwaited them).

Don't panic; keep your head; make a plan and execute it. Save your emotional reaction for when the job is done. If an eight-year-old can do it, so can we.

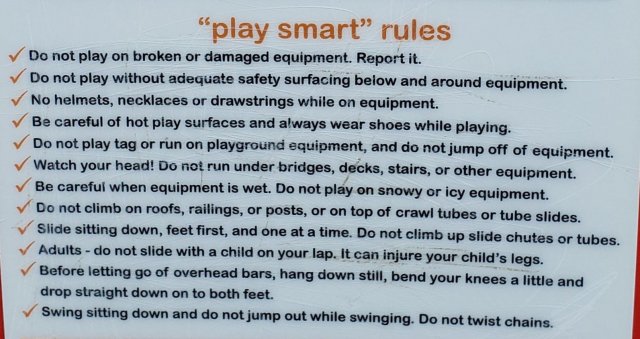

Our grandchildren's community/elementary school playground was recently updated. There was nothing obviously wrong with the old playground, which was not very old. The only obvious improvement was the addition of some equipment that could be more easily used by children with certain disabilities, which is a good thing but surely could have been accomplished without re-doing the whole thing at horrendous taxpayer expense.

Still, a playground is a playground, and this one being within walking distance for our grandchildren is a favorite destination when school is out. Everyone enjoys it, albeit on his own terms.

The first thing every one of them determined was that it was important to break every rule whenever possible. (Click to enlarge.) Beginning, of course, with the one that is not shown here: Adult supervision recommended. After all, it's only a recommendation, and we know what happened when the COVID-19 "rules" changed to "recommendations."

That gotten out of the way, it was time to notice some other interesting things about the equipment. It appears that the students at this school may grow up at a disadvantage in mathematics, at least when it comes to measurement.

I am not under five feet tall, and this is no trick of perspective. For all the money spent on this playground, couldn't they have placed the sign correctly?

On the other hand, I expect the students to have an advantage when it comes to music. How many playgrounds feature chimes in the Locrian scale?

I have no illusions that many of my readers will watch this video. Maybe no one at all. It's two hours long, and few of us have two hours to spare for a YouTube video. It's a discussion of human trafficking among David Freiheit (Viva Frei), Robert Barnes, and their guest, Eliza Bleu, a trafficking survivor and advocate. I managed to listen to it all by taking it in small bites and multitasking. Lengthy or not, the topic is important. They don't even try to deal with the more nuanced issues, such as "sex workers" whose participation is really, truly, consensual, and "slave wages" that turn out to be a family's best hope of escaping poverty. They don't even take on "legitimate pornography."

Sadly, I think this is a wise approach, if they don't want to make the mistake abortion opponents made: in that debate, too many people insisted on all-or-nothing, refusing to accept compromises that would have allowed abortions for cases of rape, incest, and where the child is so deformed that he would suffer and die soon after birth anyway. That approach was logical, in a theoretical, ethical sense—but arguing over the rare exceptions resulted in the door for abortion being opened wide and far. In the case of human trafficking, there is more than enough horror on which everyone but the perpetrators can agree; let's focus on that.

The interview is interesting from beginning to end, though that is a very poor word to describe something that can only be endured through a certain numbness and keeping the whole topic at a deliberate distance. The beginning, where Eliza tells her own story, is most interesting, especially to homeschoolers. If you're looking for another reason to hate the big social media companies, there's plenty of fodder in the later part of the video.

I'm frustrated that video is the medium of choice for so much information, especially current stories. I read so very much faster than I can listen, even pushing the video to higher speeds. Plus, anything good that is written has been through at least minimal editing, whereas with interviews, podcasts, and live streams, every um, uh, and rabbit trail remains. I find the written word to be much more efficient, usually much more dense in terms of information conveyed. But sometimes the more personal touch that can come through in a video is valuable, too.

In any case, as our choir director has taught us, it is what it is, and sometimes you have to adapt. I put this out here, (1) so I can find it again, and (2) in the off chance that someone may find it enlightening.

Part 1 of the visit of our Swiss family is here, part 2 here.

At last, Christmas drew near, and we focussed our activities nearer home. Christmas Eve saw us in church, of course, with some of our guests pressed into service in our hand chime choir. Hand chimes are not nearly as beautiful as handbells, but they are what we had. We didn't even have a handbell choir until it emerged as a desperation move to give our choir a way to make music when rehearsing and singing were forbidden. In this we were oppressed, not by the state, but by our very own bishop, whose rules were far more draconian than the governments'. I had so looked forward to being able to share with our family the absolute beauty of our high church worship, especially on such a special day, but it was not allowed to be. Nonetheless, we were grateful to be permitted in-person services at all. We were there; God was there. And some of us went back later for the midnight mass.

cropped.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

Credit for the above three photos Anke Cirillo of Three Point Photography

And then it was Christmas! Happiness is a house full of family.

After Christmas we boldly got together with our long-time friend and former choir director for one of our spontaneous music-making sessions. It's impossible to describe what a glorious outpouring of joy there is in these events. I do have a few recordings I treasure, but out of respect for the true musicians who don't always appreciate having their impromptu experimentations broadcast to the world, I'll leave it to your imagination. We had singing, piano, harmonica, viola, recorder, hand chimes, and all manner of percussion. If I could do this every night I know my mental state would take a drastic turn for the better. And the interaction between me on the tambourine and our granddaughter on the maracas was pretty good physical exercise, too.

We visited several playgrounds and natural parks, including taking the Black Point Wildlife Drive on the east coast. It's a favorite of ours, and a lovely place to see birds. On this trip, however, the more exciting views were of another sort:

And what's a trip to that part of the state without a stop at the Dixie Crossroads restaurant?

We continued to enjoy our final days of this visit, trying not to think too much about the upcoming long trip to Miami and the even longer trip across the Atlantic. And the 10-day quarantine awaiting them back in Switzerland. But they survived all that without catching COVID-19, and so did we. We are so grateful to Florida for welcoming our overseas family, to Switzerland for letting them come (and return), and to all whose efforts made this visit possible. I hadn't fully realized the toll these pandemic restrictions had taken on our mental health until we were reminded of what we were missing. I believe this visit came just in time, and I'm so glad we made the joyful choice.

This December visit seems more than six months distant, given that January and February brought us vaccines and the beginning of more freedom, at least in Florida. It would be April before the Northeast opened up enough for another healing family visit ... and that's a story for another post.

Permalink | Read 3983 times | Comments (0)

Category Hurricanes and Such: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Health: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Politics: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Children & Family Issues: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Everyday Life: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]