A Child's History of England by Charles Dickens (public domain, 1851-1853)

A Child's History of England by Charles Dickens (public domain, 1851-1853)

Dickens' book is, unsurprisingly, in the public domain. I read the free Kindle version and it was fine, though it might be worth springing for another $2 and getting the original illustrations as well.

A Child's History of England is a maddening book, yet a valuable one. According to its Wikipedia article, it "was included in the curricula of British schoolchildren well into the 20th century." It never could be now—which may be an indication that it should be. It is one man's very biased view of English history, hence valuable to balance other biases.

What's good about it? Well, I appreciated the organized layout of English history from ancient times up to the reign of William and Mary, with a very quick summary thence to Queen Victoria. Bit by bit, through several sources, I am gaining knowledge of the history of the lands that were home to many of my ancestors and played a significant part in the development of Western Civilization. The book, being designed for intelligent children, is both readable enough and interesting enough to read much more like a story than a textbook.

What didn't I like? To begin with, it is obviously and admittedly a propaganda piece. Dickens himself said of his book,

I am writing a little history of England for my boy ... For I don't know what I should do, if he were to get hold of any conservative or High Church notions; and the best way of guarding against any such horrible result is, I take it, to wring the parrots' neck in his very cradle.

Dickens does not appear to have liked England very much. He praises the Saxons, and holds Alfred the Great in very high esteem. Henry V wasn't too bad, and Oliver Cromwell gets too much credit for not being as horrible as the kings that preceded and followed him. Other than that, Dickens doesn't seem to have much respect for any of the British monarchs and their hangers-on. He also passionately hates the Catholic Church, and much of the undivided Church itself before the Reformation. The Puritans are heaped with scorn as well. He clearly claims to be a Christian, just as he claims to be an Englishman, but doesn't seem to care much for either Christianity or England. Sometimes the book feels less like a history and more like a series of ad hominem attacks. He even manages to draw a caricature of Joan of Arc as a mentally deficient peasant girl abused for others' gain.

Part and parcel of his prejudice, I believe, his his annoying habit of inconsistently referring to people sometimes by name, sometimes by title, often by nickname, and even by insult. I found this to make keeping the characters straight difficult, and I tired of flipping back several pages to try to figure out which particular duke was currently meant. It certainly doesn't help me to remember that he's talking about King James I when most of the time Dickens refers to him as "His Sowship."

For all that, I do recommend reading A Child's History of England, though only in the context of competing viewpoints. It does a good job of helping to put together the pieces of the complex puzzle that is the story of England.

Maybe you never wanted to be a rock star. Maybe you don't care much for that music and the genres it spawned. Maybe you aren't interested in a career in the music world at all.

No matter: In the first 22 minutes of this video, Rick Beato has a story to tell you, and some good advice for us all. More of his interesting personal story is told in other videos on his Everything Music channel, but this summarizes his journey and how he faced the obstacles he encountered, including being rejected twice when he applied to music school. He rambles a bit, but it's a good story.

Porter alerted me to this interesting, though highly biased, view of what's necessary for successful learning at home. It's from a Geopolitical Futures report by Antonia Colibasanu.

According to an April 2020 report by the European Commission, more than a fifth of children lack at least two of the basic resources for studying at home: their own room, reading opportunities, internet access and parental involvement (for children under 10 years old).

We can ignore the absurdity of needing internet access to learn from home, because the context of the quote is traditional classroom schooling provided from outside to children at home, rather than education per se.

What struck both of us, however, is the first "basic resource": that the child should have his own room. Granted, a quiet place to work is a great thing, but I see no reason why that implies the need for single bedrooms. And, as my friend and sometime guest poster points out, school classrooms are hardly solitary spaces. Mind you, I'm not in favor of open-plan offices, but I find it amusing that one's own room is considered necessary for learning but currently out of favor in our trendier workplaces.

Public education from home is relatively new, but of course homeschoolers have been doing it for centuries (well pre-internet, I might add), and often in the context of large families in which shared bedrooms are common. What is required is not separate bedrooms, but discipline and respect for others. I'll admit it also helps to have the ability to concentrate in the presence of distractions, especially if you live (as our grandchildren do) in a family where someone is nearly always singing or playing a musical instrument. Our own children discovered that climbing a tree was a good way to get some undistracted reading time.

Further, this insistence on single bedrooms—with its implication of small family size—ignores the tremendous educational advantage of having multiple siblings. My nephew learned math far beyond his grade level because he wanted to keep up with his brother. Our younger grandchildren see no reason why they shouldn't be learning and doing what their older siblings are, and the older ones are usually happy to help them along.

Public education is a very confining box to learn to think outside of, even when the devil drives.

Next up in this series of interesting YouTube channel subscriptions: Everything Music, by Rick Beato. I was going to say that I can't remember what introduced me to to Rick Beato's channel, but a look back at one of my own posts gave me the answer: Google apparently decided I would be interested in it, popping up a suggested video on my phone. For once they were right.

My gateway to Beato's channel was the musical abilities of his young son, Dylan. There are several Dylan videos, but this one is a good 13-minute compilation:

It turns out that the Dylan videos are but a small part of Everything Music. Beato covers so much; I'll let him give the intro (13 minutes).

Music theory, film music, modal scales, tales from his own interesting musical history, and a whole lot of modern music about which I know little and like less.

Remember what I said about Excellence and Enthusiasm?

I'm a child of the 60's, chronologically, but unlike most of my generation, I've never liked rock music, nor any of its relatives and derivatives. Granted, growing up when I did there was no getting away from it, and there were a few specific songs I did enjoy. At one point, I was even a minor fan of Jefferson Airplane, and attended one of their wild, live concerts. That point in my life, while embarrassing, reminds me of this line from C. S. Lewis' Screwtape Letters: "I have known a human defended from strong temptations to social ambition by a still stronger taste for tripe and onions." Who knows what trouble I might have gotten into in my college years had I not had a stronger taste for what is loosely called classical music?

What, specifically, don't I like about the rock genre(s)?

- The music is almost invariably played at ear-splitting volume, literally ear-damaging.

- Most of the music comes with lyrics, and with a few exceptions, I find that they range from boring to abominable.

- The heavy emphasis on pounding rhythms drives me crazy; I never have liked playing with a metronome.

- The timbre of the electric guitar, nearly ubiquitous in rock music, is one of a very few that I generally find unpleasant (saxophone is another).

Enter Rick Beato. If his son's abilities are astounding, Rick's aren't all that far behind, and his experience, knowledge, and enthusiasm keep me interested in his analysis even though most of his examples are from music I can't stand. It helps a lot that he uses short excerpts, in which neither lyrics nor pounding beats have a chance to do much harm. Plus, I control the volume.

I especially enjoy Rick's videos on modal music, as that has always interested my ear. It does seem really odd to hear him talk about modes without any reference to church music, in which modal music was once really big. But I had no idea how important modes are in rock music and film scoring, and learning through Rick's videos has been a delight. Hiding underneath all that raucous sound and those objectionable lyrics is a lot of complex and very interesting music. It's not going to make me a rock music fan, but it gives me more appreciation for the skill of the musicians behind it—if not for their sometimes questionable moral compasses. (I know, classical composers were not necessarily saints, either. There's a reason I generally prefer instrumental music.) It has also heightened my awareness of the music that undergirds our movies and television shows, and why it is often so powerful.

Here's an interesting Gustav Holtz/John Williams comparison from one of his movie music videos (16 minutes):

That's enough for an introduction; I'm sure I'll be posting more Everything Music videos in the future.

Permalink | Read 2197 times | Comments (0)

Category Reviews: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Education: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Music: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Inspiration: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] YouTube Channel Discoveries: [first] [next] [newest]

They say it's the winners who write the history books, implying that what has been written is untrue.

Nonsense. What it does mean is that it is not the whole truth.

But the solution to not enough truth is more truth. Labelling what has previously been written and taught as false—or erasing it altogether, and substituting another version with its own biases—only compounds the problem.

(I can hear the teachers now, pointing out that it's difficult enough to get students to learn any history at all, much less to absorb and ponder more than one point of view. But no one ever said good teaching was easy.)

I've mentioned before that one of the gravest consequences of simplifying the very complex Chinese written language is to cut off the common people of China from their literature and history. That is a very powerful tool in the hands of a totalitarian régime.

Nor are people living in a democracy safe. In the end, is there much difference between a people who cannot read their historical documents and those who do not? If free people don't care to keep their minds free, can tyranny be far behind? As President Ronald Reagan said, Freedom is never more than one generation away from extinction. It has to be fought for and defended by each generation.

Having just re-read, and reviewed, George Orwell's Nineteen Eighty-Four, I was especially struck when I came upon Larry P. Arnn's essay from last December, "Orwell’s 1984 and Today." As usual, I recommend reading the original; it's not long.

The totalitarian novel is a relatively new genre. In fact, the word “totalitarian” did not exist before the 20th century. The older word for the worst possible form of government is “tyranny”—a word Aristotle defined as the rule of one person, or of a small group of people, in their own interests and according to their will. Totalitarianism was unknown to Aristotle, because it is a form of government that only became possible after the emergence of modern science and technology.

In Orwell’s 1984, there are telescreens everywhere, as well as hidden cameras and microphones. Nearly everything you do is watched and heard. It even emerges that the watchers have become expert at reading people’s faces. The organization that oversees all this is called the Thought Police.

If it sounds far-fetched, look at China today: there are cameras everywhere watching the people, and everything they do on the Internet is monitored. Algorithms are run and experiments are underway to assign each individual a social score. If you don’t act or think in the politically correct way, things happen to you—you lose the ability to travel, for instance, or you lose your job. It’s a very comprehensive system. And by the way, you can also look at how big tech companies here in the U.S. are tracking people’s movements and activities to the extent that they are often able to know in advance what people will be doing. Even more alarming, these companies are increasingly able and willing to use the information they compile to manipulate people’s thoughts and decisions.

What we can know of the truth all resides in the past, because the present is fleeting and confusing and tomorrow has yet to come. The past, on the other hand, is complete. Aristotle and Thomas Aquinas go so far as to say that changing the past—making what has been not to have been—is denied even to God.

The protagonist of 1984 is a man named Winston Smith. He works for the state, and his job is to rewrite history. ... Winston’s job is to fix every book, periodical, newspaper, etc. that reveals or refers to what used to be the truth, in order that it conform to the new truth.

Totalitarianism will never win in the end—but it can win long enough to destroy a civilization. That is what is ultimately at stake in the fight we are in. We can see today the totalitarian impulse among powerful forces in our politics and culture. We can see it in the rise and imposition of doublethink, and we can see it in the increasing attempt to rewrite our history.

To present young people with a full and honest account of our nation’s history is to invest them with the spirit of freedom. ... It is to teach them that the people in the past, even the great ones, were human and had to struggle. And by teaching them that, we prepare them to struggle with the problems and evils in and around them. Teaching them instead that the past was simply wicked and that now they are able to see so perfectly the right, we do them a disservice and fit them to be slavish, incapable of developing sympathy for others or undergoing trials on their own.

It's time for my annual compilation of books read during the past year.

- Total books: 86

- Fiction: 58

- Non-fiction: 28

- Month with most books: February (15)

- Month with fewest books: December (2; not surprising, with the Stücklins visiting for a very active month)

- Most frequent authors: Arthur Ransome (14), C. S. Lewis (11), S. D. Smith (11), Tony Hillerman (10). Ransome scored so high because of my habit of periodically re-reading good books—it was his turn. This year concluded my C. S. Lewis retrospective. Smith came out with two new books this year and I like to re-read the series before indulging in the latest. Hillerman is a prolific author whose prominence was the result of my introduction to his work via a Christmas gift from last year.

Here's the alphabetical list; links are to reviews. The different colors only reflect whether or not you've followed a hyperlink. This chronological list has ratings and warnings as well.

- The Alto Wore Tweed by Mark Schweizer

- The Archer's Cup by S. D. Smith

- The Art of Construction by Mario Salvadori

- The Bible (Revised Standard Version)

- The Big Six by Arthur Ransome

- The Biggest Lie in the History of Christianity by Matthew Kelly

- The Black Star of Kingston by S. D. Smith

- The Blessing Way by Tony Hillerman

- The Books of the Apocrypha (Revised Standard Version)

- Brother Cadfael's Penance (Brother Cadfael #20) by Ellis Peters

- C. S. Lewis: A Companion and Guide by Walter Hooper

- The Child's Book of the Seasons by Arthur Ransome

- Christian Reflections by C. S. Lewis

- Coot Club by Arthur Ransome

- Coots in the North and Other Stories by Arthur Ransome

- Dance Hall of the Dead by Tony Hillerman

- Digital Minimalism by Cal Newport

- The Discarded Image: An Introduction to Medieval and Renaissance Literature by C. S. Lewis, edited by Walter Hooper

- Ember Falls by S. D. Smith

- Ember Rising by S. D. Smith (March)

- Ember Rising by S. D. Smith (November)

- Ember's End by S. D. Smith (March)

- Ember's End by S. D. Smith (November)

- An Experiment in Criticism by C. S. Lewis

- The Fallen Man by Tony Hillerman

- The First Eagle by Tony Hillerman

- The First Fowler by S. D. Smith

- The Five Little Peppers and How They Grew by Margaret Sidney

- The Four Loves by C. S. Lewis

- G. K. Chesterton and C. S. Lewis: The Riddle of Joy by edited by Michael H. Macdonald and Andrew A. Tadie

- Gertie's Leap to Greatness by Kate Beasley

- God in the Dock by C. S. Lewis

- Great Northern? by Arthur Ransome

- The Green Ember by S. D. Smith

- A Grief Observed by C. S. Lewis

- The Heretic's Apprentice (Brother Cadfael #16) by Ellis Peters

- The Hobbit by J. R. R. Tolkien

- The Holy Thief (Brother Cadfael #19) by Ellis Peters

- Killing Jesus by Bill O'Reilly and Martin Dugard

- Killing Kennedy by Bill O'Reilly and Martin Dugard

- Killing Reagan by Bill O'Reilly and Martin Dugard

- The Last Archer by S. D. Smith

- Lead Yourself First by Raymond M. Kethledge and Michael S. Erwin

- Legion by Brandon Sanderson

- Legion: Skin Deep by Brandon Sanderson

- Letters to an American Lady by C. S. Lewis, edited by Clyde S. Kilby

- Letters to Children by C. S. Lewis

- Letters to Malcolm: Chiefly on Prayer by C. S. Lewis

- Lies of the Beholder by Brandon Sanderson

- Listening Woman by Tony Hillerman

- Lord Darcy Investigates by Randall Garrett

- The Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring by J. R. R. Tolkien

- The Lord of the Rings: The Return of the King by J. R. R. Tolkien

- The Lord of the Rings: The Two Towers by J. R. R. Tolkien

- The Lost Family by Libby Copeland

- Matthew Wolfe: The Making of Matthew Wolfe by Blair Bancroft

- Missee Lee by Arthur Ransome

- Murder and Magic by Randall Garrett

- The New Testament (English Standard Version)

- Nineteen Eighty-Four: A Novel by George Orwell

- Of Other Worlds: Essays and Stories by C. S. Lewis

- The Omega Document by J. Alexander McKenzie

- Peter Duck by Arthur Ransome

- The Picts and the Martyrs by Arthur Ransome

- Pigeon Post by Arthur Ransome

- The Potter's Field (Brother Cadfael #17) by Ellis Peters

- The Psalter by Coverdale translation

- The Quotable Lewis edited by Wayne Martindale and Jerry Root

- Secret Water by Arthur Ransome

- The Shape Shifter by Tony Hillerman

- The Sinister Pig by Tony Hillerman

- Skinwalkers by Tony Hillerman

- Starman Jones by Robert Heinlein

- Starship Troopers by Robert Heinlein

- The Summer of the Danes (Brother Cadfael #18) by Ellis Peters

- Surprised Laughter: The Comic World of C. S. Lewis by Terry Lindvall

- Swallowdale by Arthur Ransome

- Swallows and Amazons by Arthur Ransome

- Talking God by Tony Hillerman

- A Thief of Time by Tony Hillerman

- Too Many Magicians by Randall Garrett

- We Didn't Mean to Go to Sea by Arthur Ransome

- Winter Holiday by Arthur Ransome

- The World's Last Night and other Essays by C. S. Lewis

- The Wreck and Rise of Whitson Mariner by S. D. Smith

- Your Blue Flame: Drop the Guilt and Do What Makes You Come Alive by Jennifer Fulwiler

This is not my own, but the person I learned it from can't remember where she first found it. And it's not a direct quotation, because I've modified it to sound better in my own ears. But the sentiment is exactly the same.

"A writer is a writer not because he has amazing talent. A writer is a writer because, even when nothing he does shows any sign of promise, he keeps on writing anyway."

Digital Minimalism: Choosing a Focused Life in a Noisy World by Cal Newport (Portfolio/Penguin 2019)

Digital Minimalism: Choosing a Focused Life in a Noisy World by Cal Newport (Portfolio/Penguin 2019)

Janet recommended this one to me, and after checking out Newport's TED talk, "Why You Should Quit Social Media," I decided to reserve it at the library. I had to wait in line; maybe more than a few people are rethinking Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, Old Uncle Tom Cobleigh and all.

Digital Minimalism is divided into two parts: Foundations, and Practices. I read through Foundations easily, able to enjoy the book without pasting sticky tabs all over it. For me, this is like going somewhere and not taking pictures. Those sticky notes represent text that I will later laboriously transcribe for my reviews. As with the photos, something is gained but something is lost. I was enjoying the book and anticipating an easy review.

Then I hit Practices. Or Practices hit me.

The first chapter of that section, "Spend Time Alone," is about solitude deprivation. I could have sticky-noted the whole chapter. Here is me, restraining myself:

Everyone benefits from regular doses of solitude, and, equally important, anyone who avoids this state for an extended period of time will ... suffer. ... Regardless of how you decide to shape your digital ecosystem, you should give your brain the regular doses of quiet it requires to support a monumental life. (pp. 91-92).

[Raymond] Kethledge is a respected judge serving on the United States Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit, and [Michael] Erwin is a former army officer who served in both Iraq and Afghanistan. ... [Their book on the topic of solitude], Lead Yourself First ... summarizes, with the tight logic you expect from a federal judge and former military officer, [their] case for the importance of being alone with your thoughts. Before outlining their case, however, the authors start with what is arguably one of their most valuable contributions, a precise definition of solitude. Many people mistakenly associate this term with physical separation—requiring, perhaps, that you hike to a remote cabin miles from another human being. This flawed definition introduces a standard of isolation that can be impractical for most to satisfy on any sort of a regular basis. As Kethledge and Erwin explain, however, solitude is about what’s happening in your brain, not the environment around you. Accordingly, they define it to be a subjective state in which your mind is free from input from other minds. (pp. 92-93)

You can enjoy solitude in a crowded coffee shop, on a subway car, or, as President Lincoln discovered at his cottage, while sharing your lawn with two companies of Union soldiers, so long as your mind is left to grapple only with its own thoughts. On the other hand, solitude can be banished in even the quietest setting if you allow input from other minds to intrude. In addition to direct conversation with another person, these inputs can also take the form of reading a book, listening to a podcast, watching TV, or performing just about any activity that might draw your attention to a smartphone screen. Solitude requires you to move past reacting to information created by other people and focus instead on your own thoughts and experiences—wherever you happen to be. (pp. 93-94).

Regular doses of solitude, mixed in with our default mode of sociality, are necessary to flourish as a human being. It’s more urgent now than ever that we recognize this fact, because ... for the first time in human history solitude is starting to fade away altogether. (p. 99)

The concern that modernity is at odds with solitude is not new. ... The question before us, then, is whether our current moment offers a new threat to solitude that is somehow more pressing than those that commentators have bemoaned for decades. ... To understand my concern, the right place to start is the iPod revolution that occurred in the first years of the twenty-first century. We had portable music before the iPod ... but these devices played only a restricted role in most people’s lives—something you used to entertain yourself while exercising, or in the back seat of a car on a long family road trip. If you stood on a busy city street corner in the early 1990s, you would not see too many people sporting black foam Sony earphones on their way to work. By the early 2000s, however, if you stood on that same street corner, white earbuds would be near ubiquitous. The iPod succeeded not just by selling lots of units, but also by changing the culture surrounding portable music. It became common, especially among younger generations, to allow your iPod to provide a musical backdrop to your entire day—putting the earbuds in as you walk out the door and taking them off only when you couldn’t avoid having to talk to another human. (pp. 99-100).

This transformation started by the iPod, however, didn’t reach its full potential until the release of its successor, the iPhone.... Even though iPods became ubiquitous, there were still moments in which it was either too much trouble to slip in the earbuds (think: waiting to be called into a meeting), or it might be socially awkward to do so (think: sitting bored during a slow hymn at a church service). The smartphone provided a new technique to banish these remaining slivers of solitude: the quick glance. (p. 101)

When you avoid solitude, you miss out on the positive things it brings you: the ability to clarify hard problems, to regulate your emotions, to build moral courage, and to strengthen relationships. (p. 104)

Eliminating solitude also introduces new negative repercussions that we’re only now beginning to understand. A good way to investigate a behavior’s effect is to study a population that pushes the behavior to an extreme. When it comes to constant connectivity, these extremes are readily apparent among young people born after 1995—the first group to enter their preteen years with access to smartphones, tablets, and persistent internet connectivity. ... If persistent solitude deprivation causes problems, we should see them show up here first. ...

The head of mental health services at a well-known university ... told me that she had begun seeing major shifts in student mental health. ... Seemingly overnight the number of students seeking mental health counseling massively expanded, and the standard mix of teenage issues was dominated by something that used to be relatively rare: anxiety. ... The sudden rise in anxiety-related problems coincided with the first incoming classes of students that were raised on smartphones and social media. She noticed that these new students were constantly and frantically processing and sending messages. ...

[San Diego State University psychology professor Jean Twenge observed that] young people born between 1995 and 2012 are ... on the brink of the worst mental-health crisis in decades. ... [She] made it clear that she didn’t set out to implicate the smartphone: “It seemed like too easy an explanation for negative mental-health outcomes in teens,” but it ended up the only explanation that fit the timing. Lots of potential culprits, from stressful current events to increased academic pressure, existed before the spike in anxiety.... The only factor that dramatically increased right around the same time as teenage anxiety was the number of young people owning their own smartphones. ...

When journalist Benoit Denizet-Lewis investigated this teen anxiety epidemic in the New York Times Magazine, he also discovered that the smartphone kept emerging as a persistent signal among the noise of plausible hypotheses. “Anxious kids certainly existed before Instagram,” he writes, “but many of the parents I spoke to worried that their kids’ digital habits—round-the-clock responding to texts, posting to social media, obsessively following the filtered exploits of peers—were partly to blame for their children’s struggles.” Denizet-Lewis assumed that the teenagers themselves would dismiss this theory as standard parental grumbling, but this is not what happened. “To my surprise, anxious teenagers tended to agree.” A college student he interviewed at a residential anxiety treatment center put it well: “Social media is a tool, but it’s become this thing that we can’t live without that’s making us crazy.” (pp. 104-107)

The pianist Glenn Gould once proposed a mathematical formula for this cycle, telling a journalist: “I’ve always had a sort of intuition that for every hour you spend with other human beings you need X number of hours alone. Now what that X represents I don’t really know . . . but it’s a substantial ratio.” (p. 111)

The past two decades ... are characterized by the rapid spread of digital communication tools—my name for apps, services, or sites that enable people to interact through digital networks—which have pushed people’s social networks to be much larger and much less local, while encouraging interactions through short, text-based messages and approval clicks that are orders of magnitude less information laden than what we have evolved to expect. ... Much in the same way that the “innovation” of highly processed foods in the mid-twentieth century led to a global health crisis, the unintended side effects of digital communication tools—a sort of social fast food—are proving to be similarly worrisome.(p. 136).

After winning me over with the chapter on solitude deprivation, Newport lost me somewhat with his approach to taming the beasts. The basic problem is that, for a guy who has written several books and has his own blog, he seems to have very little respect for the written word.

Many people think about conversation and connection as two different strategies for accomplishing the same goal of maintaining their social life. This mind-set believes that there are many different ways to tend important relationships in your life, and in our current modern moment, you should use all tools available—spanning from old-fashioned face-to-face talking, to tapping the heart icon on a friend’s Instagram post.

The philosophy of conversation-centric communication takes a harder stance. It argues that conversation is the only form of interaction that in some sense counts toward maintaining a relationship. This conversation can take the form of a face-to-face meeting, or it can be a video chat or a phone call—so long as it matches Sherry Turkle’s criteria of involving nuanced analog cues, such as the tone of your voice or facial expressions. Anything textual or non-interactive—basically, all social media, email, text, and instant messaging—doesn’t count as conversation and should instead be categorized as mere connection. (p. 147)

I heartily disagree with his lumping e-mail in with "all social media, text, and instant messaging." I will grant that most social media, texts, WhatsApp, IM, and the like are severely limited by the difficulty of creating the message. Phones simply are not designed for high-speed typing, and I don't know about other people's experiences, but for me voice-to-text makes so many errors I spend almost as much time correcting as I would have laboriously pecking out a message on the tiny keyboard. (That's why I much prefer WhatsApp, where I can type my messages on the computer keyboard, to texting, where I can't.) So messages tend to be short, of restricted vocabulary and complexity, and full of nasty abbreviations. But e-mails are simply typed letters that get delivered with much more speed than the mail can achieve. I will grant that you miss the tone-of-voice cues that can be heard over the phone, but I think that's often more than made up for by the ability to both speak and listen without interruption. On the phone, if I turn all my attention to what the other person is saying, there's a long silence when it's my turn to talk while I think of how I want to respond. But if I try to figure that out while the other person is speaking, I'm likely to miss, or mis-interpret what is said. And when I'm speaking, it's more than likely that I will get interrupted before getting out my entire thought, and the conversation will veer off in another direction, leaving my response incomplete and likely mis-understood. E-mail leaves plenty of time for listening, thinking, and responding.

Newport has serious problems with Facebook's "Like" button. I can see his point in some respects.

The “Like” feature evolved to become the foundation on which Facebook rebuilt itself from a fun amusement that people occasionally checked, to a digital slot machine that began to dominate its users’ time and attention. This button introduced a rich new stream of social approval indicators that arrive in an unpredictable fashion—creating an almost impossibly appealing impulse to keep checking your account. It also provided Facebook much more detailed information on your preferences, allowing their machine-learning algorithms to digest your humanity into statistical slivers that could then be mined to push you toward targeted ads and stickier content. (p. 192)

I do get the slot-machine analogy. We all crave (positive) feedback for whatever of ourselves we have put "out there." And the temptation to keep checking is real. It reminds me of the joke from 'way back in the America Online days, in which the person sitting at the computer (no smart phones back then) checks his mail, sees that there is none waiting for him—and immediately checks again. It was funny because that's what so many people did. But I think Newport misunderstands how many of us use the Like button.

In the context of this chapter, however, I don’t want to focus on the boon the “Like” button proved to be for social media companies. I want to instead focus on the harm it inflicted to our human need for real conversation. To click “Like,” within the precise definitions of information theory, is literally the least informative type of nontrivial communication, providing only a minimal one bit of information about the state of the sender (the person clicking the icon on a post) to the receiver (the person who published the post). Earlier, I cited extensive research that supports the claim that the human brain has evolved to process the flood of information generated by face-to-face interactions. To replace this rich flow with a single bit is the ultimate insult to our social processing machinery. (p. 153)

But here's the thing. I don't know anyone who pretends that clicking "Like" or "Love" or "I care" is conversation. However, it is the digital equivalent of one part of a successful conversation: the nod, the smile, the grunt, the frown, the short interjection, which in face-to-face conversation we used as an important lubricant to keep a conversation running smoothly. It hardly communicates any more information than the Facebook buttons; maybe it's little more than a bit—but it's an important bit. It says, "I'm listening, I hear you, I agree, keep talking," or "Wait, what you said confuses me, or angers me," or "I'm sorry, I sympathize."

As soon as easier communication technologies were introduced—text messages, emails—people seemed eager to abandon this time-tested method of conversation for lower-quality connections (Sherry Turkle calls this effect “phone phobia”). (p. 160)

Guilty as charged, but there's no need for Newport (or Turkle) to be snarky about it. I'm hardly alone, and there's ample evidence that phone phobia is attached to the same set of genes that makes me like mathematics. I love the (true) story a colleague told of a bunch of math grad students who decided to order pizza. Every one of them hemmed and hawed and delayed making the order, until the wife of one of the mathematicians, herself a grad student in philosophy, sighed, "For Pete's sake!" and called the restaurant. Text-based communication is a real boon to people like us. Call it a disability if you like—and then remember that you shouldn't mock or discriminate against people with disabilities.

Fortunately, there’s a simple practice that can help you sidestep these inconveniences and make it much easier to regularly enjoy rich phone conversations. I learned it from a technology executive in Silicon Valley who innovated a novel strategy for supporting high-quality interaction with friends and family: he tells them that he’s always available to talk on the phone at 5:30 p.m. on weekdays. There’s no need to schedule a conversation or let him know when you plan to call—just dial him up. As it turns out, 5:30 is when he begins his traffic-clogged commute home in the Bay Area. He decided at some point that he wanted to put this daily period of car confinement to good use, so he invented the 5:30 rule. The logistical simplicity of this system enables this executive to easily shift time-consuming, low-quality connections into higher-quality conversation. If you write him with a somewhat complicated question, he can reply, “I’d love to get into that. Call me at 5:30 any day you want.” Similarly, when I was visiting San Francisco a few years back and wanted to arrange a get-together, he replied that I could catch him on the phone any day at 5:30, and we could work out a plan. When he wants to catch up with someone he hasn’t spoken to in a while, he can send them a quick note saying, “I’d love to get up to speed on what’s going on in your life, call me at 5:30 sometime.” ... He hacked his schedule in such a way that eliminated most of the overhead related to conversation and therefore allowed him to easily serve his human need for rich interaction. (pp. 161-162)

I have to say, that strikes me as more selfish than clever. It's saying to everyone else that he will only communicate with them through his own preferred medium. Granted, it's his right to do so, and maybe he's learned that that's the best way he can get the most accomplished. But I'd have to be pretty desperate to call someone who I knew was going to be driving while he is talking with me. Either he's not going to be giving me his full attention, or he's not going to be giving the other cars on the road his full attention, neither one of which strikes me as ideal. And if I have a complicated question, I definitely want the response to be by written word, where there's a record of what was said, and more chance of getting a well thought out response.

I’ve seen several variations of this practice work well. Using a commute for phone conversations, like the executive introduced above, is a good idea if you follow a regular commuting schedule. It also transforms a potentially wasted part of your day into something meaningful. Coffee shop hours are also popular. In this variation, you pick some time each week during which you settle into a table at your favorite coffee shop with the newspaper or a good book. The reading, however, is just the backup activity. You spread the word among people you know that you’re always at the shop during these hours with the hope that you soon cultivate a rotating group of regulars that come hang out. ... You can also consider running these office hours once a week during happy hour at a favored bar. (pp. 162-163)

<Shudder> Really? I'm supposed to go to the expense, inconvenience, and annoyance of sitting around at a coffee shop or bar on spec, just hoping a friend shows up? And expect my friends to be willing to pay an insane amount for a cup of coffee just to talk with me? Here, and in many other places in Digital Minimalism, you can tell that Newport is an extrovert—with plenty of spare cash—and friends who are the same.

And anyway, whatever happened to visiting people in their homes? One friend of ours decided to quit Facebook, and in her final message invited anyone in town to drop by her house for tea. I could get into that. If you're willing to get out and drive to a restaurant, come instead and knock at our door. You'll be more than welcome and none one of us will have to buy an expensive drink. (This pandemic won't last forever.)

[In the early 20th century, Arnold Bennett, author of How to Live on 24 Hours a Day, speaking of leisure activities] argues that these hours should instead be put to use for demanding and virtuous leisure activities. Bennett, being an early twentieth-century British snob, suggests activities that center on reading difficult literature and rigorous self-reflection. In a representative passage, Bennett dismisses novels because they “never demand any appreciable mental application.” A good leisure pursuit, in Bennett’s calculus, should require more “mental strain” to enjoy (he recommends difficult poetry). (p. 175)

Newport approves of the idea that "the value you receive from a pursuit is often proportional to the energy invested." But then he adds,

For our twenty-first-century purposes, we can ignore the specific activities Bennett suggests. (p. 175)

And what, pray tell, is snobbish or unreasonable about literature and poetry?

Newport has a lot to say about the value of craft: of woodworking, or renovating a bathroom, or repairing a motorcycle, or knitting a sweater. He includes musical performances as well. But—and I find this odd for an author—he seems to have little respect for creating books. Would it be a more noble activity if they were typed on an old Remington, or handwritten? He similarly discounts composing music using a computer as less worthwhile than playing a guitar. I don't buy it.

The following story is for our two oldest grandsons, who have a way of picking up and enjoying construction skills.

[Pete's] welding odyssey began in 2005. At the time, he was building a custom home. ... The house was modern so Pete integrated some custom metalwork into his design plan, including a beautiful custom steel railing on the stairs.

The design seemed like a great idea until Pete received a quote from his metal contractor for the work: it was for $15,800, and Pete had budgeted only $4,000. “If this guy is billing out his metalworking time at $75.00 an hour, that’s a sign that I need to finally learn the craft myself,” Pete recalls thinking at the time. “How hard can it be?” In Pete’s hands, the answer turned out to be: not that hard.

Pete bought a grinder, a metal chop saw, a visor, heavy-duty gloves, and a 120-volt wire-feed flux core welder—which, as Pete explains, is by far the easiest welding device to learn. He then picked some simple projects, loaded up some YouTube videos, and got to work. Before long, Pete became a competent welder—not a master craftsman, but skilled enough to save himself tens of thousands of dollars in labor and parts. (As Pete explains it, he can’t craft a “curvaceous supercar,” but he could certainly weld up a “nice Mad-Max-style dune buggy.”) In addition to completing the railing for his custom home project (for much less than the $15,800 he was quoted), Pete went on to build a similar railing for a rooftop patio on a nearby home. He then started creating steel garden gates and unusual plant holders. He built a custom lumber rack for his pickup truck and fabricated a series of structural parts for straightening up old foundations and floors in the historic homes in his neighborhood. As Pete was writing his post on welding, a metal attachment bracket for his garage door opener broke. He easily fixed it. (pp. 194-195)

If you're wondering where to learn skills needed for simple projects ... the answer is easy. Almost every modern-day handyperson I've spoken to recommends the exact same source for quick how-to lessons: YouTube. (pp. 197-198, emphasis mine)

In the middle of a busy workday, or after a particularly trying morning of childcare, it’s tempting to crave the release of having nothing to do—whole blocks of time with no schedule, no expectations, and no activity beyond whatever seems to catch your attention in the moment. These decompression sessions have their place, but their rewards are muted, as they tend to devolve toward low-quality activities like mindless phone swiping and half-hearted binge-watching. ... Investing energy into something hard but worthwhile almost always returns much richer rewards. (p. 212)

Finally, I can't resist his description of former Kickstarter project called the Light Phone.

Here’s how it works. Let’s say you have a Light Phone, which is an elegant slab of white plastic about the size of two or three stacked credit cards. This phone has a keypad and a small number display. And that’s it. All it can do is receive and make telephone calls—about as far as you can get from a modern smartphone while still technically counting as a communication device.

Assume you’re leaving the house to run some errands, and you want freedom from constant attacks on your attention. You activate your Light Phone through a few taps on your normal smartphone. At this point, any calls to your normal phone number will be forwarded to your Light Phone. If you call someone from it, the call will show up as coming from your normal smartphone number as well. When you’re ready to put the Light Phone away, a few more taps turns off the forwarding. This is not a replacement for your smartphone, but instead an escape hatch that allows you to take long breaks from it. (p. 245).

Despite our areas of disagreement, there's only one really, really annoying section of the book. He spends seven pages on the ideas of someone named Jennifer who "prefers the pronoun 'they/their' to 'she/her'." The ideas are not worth the ensuing confusion between singular and plural. I found myself constantly re-reading trying to figure out who was being referenced in the text.

But I do recommend reading Digital Minimalism. The concept of solitude deprivation alone would make it worthwhile, and the rest of the book is pretty good, too—especially if you're not a phone-phobic, introverted author.

Permalink | Read 2283 times | Comments (6)

Category Reviews: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Education: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Health: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Computing: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Children & Family Issues: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Social Media: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

Recently I stumbled upon The Conservative Student's Survival Guide. It's a five-minute video offering advice to—you guessed it—conservative students who find themselves a despised minority on liberal college campuses. That's no joke: for all the talk you'll hear from academia about tolerance, liberal values, and minority rights, it's a jungle out there if your particular minority isn't currently in favor, and it seems the only status more dangerous than "conservative student" on most American campuses is "conservative faculty." It was true when we were in college, it was true when our children were in college—and everything I see leads me to believe the situation is far, far worse now.

What's surprising about this video is that, unlike much that comes from both Left and Right these days, it is calm, well-reasoned, and respectful. What's more, even though it's aimed at conservative students, any thoughtful person who wants to make the most of his college experience would do well to consider this advice.

The speaker is Matthew Woessner, a Penn State political science professor. All of his seven suggestions make sense, but my top three are these:

- Avoid pointless ideological battles. It's not your job to convert your professors or your fellow students. Discuss and debate, but don't push too hard.

- Choose [your classes and your major] wisely. I was a liberal atheist in college, but much on campus was too far Left even for me. Being a student of the hard sciences saved me from a great deal of the insanity that was going on in the humanities and social sciences departments. A quarter-century later, one of our daughters found some of the same relief as an engineering major. Our other daughter, however, discovered that life at a music conservatory was quite difficult—despite the name, conservative values were not welcome.

- Work hard—college faculty value hard-working, enthusiastic students. I'd say this is the most valuable of all his points. Excellence and enthusiasm are attractive. A student who participates respectfully in class, does the work, and learns the material will gain the respect and appreciation of most of his professors. Teachers are like that.

C. S. Lewis wrote the Preface to a book by B. G. Sandhurst entitled How Heathen is Britain? This essay has been republished as the thirteenth chapter of Lewis's book, God in the Dock, which I recently finished re-reading. I deemed the excerpts below too extensive for my review of that book, so here they are in their own post.

The essay, written in the mid-1940's, deals largely with the effect of state education on students' beliefs and attitudes about the Christian faith. A few quotes can't do justice to the logic of the argument, but should suffice to give the flavor. All bold emphasis is my own.

The content of, and the case for, Christianity, are not put before most schoolboys under the present system; ... when they are so put a majority find them acceptable. ... [These two facts] blow away a whole fog of "reasons for the decline of religion" which are often advanced and often believed. If we had noticed that the young men of the present day found it harder and harder to get the right answers to sums, we should consider that this had been adequately explained the moment we discovered that schools had for some years ceased to teach arithmetic. (p. 115)

The sources of unbelief among young people today do not lie in those young people. The outlook which they have—until they are taught better—is a backwash from an earlier period. It is nothing intrinsic to themselves which holds them back from the Faith. This very obvious fact—that each generation is taught by an earlier generation—must be kept very firmly in mind. (p. 116)

No generation can bequeath to its successor what it has not got. You may frame the syllabus as you please. But when you have planned and reported ad nauseam, if we are skeptical we shall teach only skepticism to our pupils, if fools only folly, if vulgar only vulgarity, if saints sanctity, if heroes heroism. ... Nothing which was not in the teachers can flow from them into the pupils. (p. 116)

A society which is predominantly Christian will propagate Christianity through its schools: one which is not, will not. All the ministries of education in the world cannot alter this law. We have, in the long run, little either to hope or fear from government.

The State may take education more and more firmly under its wing. I do not doubt that by so doing it can foster conformity, perhaps even servility, up to a point; the power of the State to deliberalize a profession is undoubtedly very great. But all the teaching must still be done by concrete human individuals. The State has to use the men who exist. Nay, as long as we remain a democracy, it is men who give the State its powers. And over these men, until all freedom is extinguished, the free winds of opinion blow. Their minds are formed by influences which government cannot control. And as they come to be, so will they teach. ... Let the abstract scheme of education be what it will: its actual operation will be what the men make it. ... Your "reform" may incommode and overwork them, but it will not radically alter the total effect of their teaching. (pp. 116-117)

Where the tide flows towards increasing State control, Christianity, with its claims in one way personal and in the other way ecumenical and both ways antithetical to omnicompetent government, must always in fact (though not for a long time yet in words) be treated as an enemy. Like learning, like the family, like any ancient and liberal profession, like the common law, it gives the individual a standing ground against the State. Hence Rousseau, the father of the totalitarians, said wisely enough, from his own point of view, of Christianity, Je ne connais rien de plus contraire à l'esprit social ("I know nothing more opposed to the social spirit"). ... Even if we were permitted to force a Christian curriculum on the existing schools with the existing teachers we should only be making masters hypocrites and hardening thereby the pupils' hearts. (p. 118)

I am speaking, of course, of large schools on which a secular character is already stamped. If any man, in some little corner out of the reach of the omnicompetent, can make, or preserve a really Christian school, that is another matter. His duty is plain. (p. 119)

What a society has, that, be sure, and nothing else, it will hand on to its young. The work is urgent, for men perish around us. But there is no need to be uneasy about the ultimate event. As long as Christians have children and non-Christians do not, one need have no anxiety for the next century. (p. 119)

Clearly Lewis did not anticipate that Christians would embrace the radical move to very small families nearly as much as secular society did. I'm thankful for those who are now reversing that trend. The idea is mocked today ("evangelism by procreation"), but Lewis—though he had a difficult home life and no biological children of his own—clearly recognized the life- and faith-affirming value of begetting and bearing children in Christian families.

As for the rest of the quotations: it is still true that democratic governments have much less control over what children think and learn than they would like. But the same is now also true of teachers. Lewis was thinking of the influence of teachers when he wrote,

Planning has no magic whereby it can elicit figs from thistles or choke-pears from vines. The rich, sappy, fruit-laden tree will bear sweetness and strength and spiritual health; the dry, prickly, withered tree will teach hate, jealousy, suspicion, and inferiority ... [no matter what] you tell it to teach. (pp. 117-118)

This is even more true, now, of the movies, music, and other media that are the very air our young people breathe (and rarely think about), and of the peer-oriented society we have bequeathed them. As I wrote in my review of Gordon Neufeld and Gabor Maté's book Hold On to Your Kids (a book I strongly recommend to all parents, grandparents, teachers, pastors, and anyone else who cares about children),

It is essential to the survival of a civilization that its culture be passed on from one generation to another. Today's children are not receiving culture, they are inventing it as they go along. We are into the third generation of this problem, and appear to be reaching a tipping point. If the idea of peer culture being more important to children than their family culture doesn't seem strange and wrong to us, it's because that's how we grew up, too.

I've never liked William Golding's book, The Lord of the Flies. Why high school English teachers think it helpful to assault students' spirits with the distressing imaginations of disturbed minds, I cannot imagine. My daughter hated it even more than I did, and although she finished reading the book weeks before the school exam, she steadfastly refused to reread or study it in any way. She'd rather fail, she insisted. (Actually, she aced the test. Having a good memory is both a curse and a blessing.)

The Lord of the Flies certainly hit a chord with popular society, and like it or not has become part of our culture. Say to someone, "it's a Lord of the Flies situation there," and he knows exactly what you mean. It has also contributed to a good deal of negative and cynical thinking.

My sister-in-law, who knows my feelings on the matter, sent me this marvellous story about a real-life event that illustrates just the opposite about human behavior. (Warning: if you read the article, you may have to ignore some incidental, intense political ranting; I don't know what extras might be showing when you get there, but the last time I saw it I almost decided not to include the link. But credit must go where credit it due.) Here are some excerpts with the bare bones of the story:

This story [of the degradation and brutal behavior of castaway English schoolboys] never happened. An English schoolmaster, William Golding, made up this story in 1951—his novel Lord of the Flies would sell tens of millions of copies, be translated into more than 30 languages and hailed as one of the classics of the 20th century. In hindsight, the secret to the book’s success is clear. Golding had a masterful ability to portray the darkest depths of mankind. Of course, he had the zeitgeist of the 1960s on his side. (emphasis mine)

Years later when I began delving into the author’s life. I learned what an unhappy individual he had been: an alcoholic, prone to depression. “I have always understood the Nazis,” Golding confessed, “because I am of that sort by nature.” And it was “partly out of that sad self-knowledge” that he wrote Lord of the Flies.

I began to wonder: had anyone ever studied what real children would do if they found themselves alone on a deserted island? I wrote an article on the subject, in which I compared Lord of the Flies to modern scientific insights and concluded that, in all probability, kids would act very differently. Readers responded sceptically. All my examples concerned kids at home, at school, or at summer camp. Thus began my quest for a real-life Lord of the Flies. After trawling the web for a while, I came across an obscure blog that told an arresting story: “One day, in 1977, six boys set out from Tonga on a fishing trip ... Caught in a huge storm, the boys were shipwrecked on a deserted island. What do they do, this little tribe? They made a pact never to quarrel.”

It took some work to uncover the source of the story, as the date given was incorrect; the real year was 1966.

The real Lord of the Flies ... began in June 1965. The protagonists were six boys—Sione, Stephen, Kolo, David, Luke and Mano—all pupils at a strict Catholic boarding school in Nuku‘alofa [the capital of Tonga]. The oldest was 16, the youngest 13, and they had one main thing in common: they were bored witless. So they came up with a plan to escape: to Fiji, some 500 miles away, or even all the way to New Zealand.

The boys "borrowed" a small sailing boat, and their voyage started out fine, with fair skies and a mild breeze.

But that night the boys made a grave error. They fell asleep. A few hours later they awoke to water crashing down over their heads. It was dark. They hoisted the sail, which the wind promptly tore to shreds. Next to break was the rudder. “We drifted for eight days,” Mano told me. “Without food. Without water.” The boys tried catching fish. They managed to collect some rainwater in hollowed-out coconut shells and shared it equally between them, each taking a sip in the morning and another in the evening. Then, on the eighth day, they spied a miracle on the horizon. A small island, to be precise. Not a tropical paradise with waving palm trees and sandy beaches, but a hulking mass of rock, jutting up more than a thousand feet out of the ocean.

These days, the island is considered uninhabitable. But by the time the boys were rescued, 15 months later,

[They] had set up a small commune with food garden, hollowed-out tree trunks to store rainwater, a gymnasium with curious weights, a badminton court, chicken pens and a permanent fire, all from handiwork, an old knife blade and much determination.” While the boys in Lord of the Flies come to blows over the fire, those in this real-life version tended their flame so it never went out, for more than a year.

The kids agreed to work in teams of two, drawing up a strict roster for garden, kitchen and guard duty. Sometimes they quarrelled, but whenever that happened they solved it by imposing a time-out. Their days began and ended with song and prayer. Kolo fashioned a makeshift guitar from a piece of driftwood, half a coconut shell and six steel wires salvaged from their wrecked boat ... and played it to help lift their spirits. And their spirits needed lifting. All summer long it hardly rained, driving the boys frantic with thirst. They tried constructing a raft in order to leave the island, but it fell apart in the crashing surf.

Worst of all, Stephen slipped one day, fell off a cliff and broke his leg. The other boys picked their way down after him and then helped him back up to the top. They set his leg using sticks and leaves. “Don’t worry,” Sione joked. “We’ll do your work, while you lie there like King Taufa‘ahau Tupou himself!”

They survived initially on fish, coconuts, tame birds (they drank the blood as well as eating the meat); seabird eggs were sucked dry. Later, when they got to the top of the island, they found an ancient volcanic crater, where people had lived a century before. There the boys discovered wild taro, bananas and chickens (which had been reproducing for the 100 years since the last Tongans had left).

They were finally rescued on Sunday 11 September 1966. The local physician later expressed astonishment at their muscled physiques and Stephen’s perfectly healed leg.

The article has much more of the story, including how the rescued boys were immediately clapped into jail for having stolen the boat. (It ends well.)

This is a much better story than The Lord of the Flies, and it's true. Sadly, it's unlikely to have the social impact of Golding's book. But I hope all English teachers who insist on teaching Golding will be inspired to include the real story in their discussions. At the very least, parents now have an antidote to offer their distressed children.

And we all have an antidote to the evening news and social media.

It's time for my annual compilation of books read during the past year. A few patterns stand out: my current C. S. Lewis retrospective; the discovery of several new Rick Brant Science-Adventure books, necessitating a re-read of the whole series; the release of a new Green Ember book, ditto; and the discovery in July of the Brother Cadfael books. Mystery and adventure were heavily represented this year; hence so was fiction. Here are a few statistics:

- Total books: 92, not up to last year's 108, but more than any other year since I started keeping track in 2010

- Fiction 61, non-fiction 22, other 9

- Months with most books: February and December, tied at 15

- Months with fewest books: September, not a one; June had only two; travel is another way of expanding one's horizons

- Most frequent authors: John Blaine (Harold L. Goodwin) 24; C. S. Lewis 23; Ellis Peters 16

Here's the alphabetical list; links are to reviews. Titles in bold are ones I found particularly worthwhile, but the different colors only reflect whether or not you've followed a hyperlink. This chronological list has ratings and warnings as well.

- 100 Fathoms Under: A Rick Brant Science-Adventure Story #4 by John Blaine

- 3000 Quotations from the Writings of George MacDonald by Harry Verploegh (ed.)

- The Abolition of Man by C. S. Lewis

- The Armchair Economist: Economics and Everyday Life by Steven E. Landsburg

- The Bible (The Message paraphrase)

- The Black Star of Kingston by S. D. Smith

- The Blue Ghost Mystery: A Rick Brant Science-Adventure Story #15 by John Blaine

- A Book of Narnians: The Lion, the Witch and the Others by C. S. Lewis, James Riordan, Pauline Baynes

- The Books of the Apocrypha

- The Business of Heaven: Daily Readings from C. S. Lewis by Walter Hooper (ed.)

- C. S. Lewis on Scripture by Michael J. Christensen

- The Caves of Fear: A Rick Brant Science-Adventure Story #8 by John Blaine

- The Chronicles of Narnia 1: The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe by C. S. Lewis

- The Chronicles of Narnia 2: Prince Caspian by C. S. Lewis

- The Chronicles of Narnia 3: The Voyage of the Dawn Treader by C. S. Lewis

- The Chronicles of Narnia 4: The Silver Chair by C. S. Lewis

- The Chronicles of Narnia 5: The Horse and His Boy by C. S. Lewis

- The Chronicles of Narnia 6: The Magician's Nephew by C. S. Lewis

- The Chronicles of Narnia 7: The Last Battle by C. S. Lewis

- The Confession of Brother Haluin (Brother Cadfael #15) by Ellis Peters

- The Crusades Controversy: Setting the Record Straight by Thomas F. Madden

- Danger Below!: A Rick Brant Science-Adventure Story #23 by John Blaine

- Dead Man's Ransom (Brother Cadfael #9) by Ellis Peters

- The Deadly Dutchman: A Rick Brant Science-Adventure Story #22 by John Blaine

- Decisive by Chip Heath and Dan Heath

- The Devil's Novice (Brother Cadfael #8) by Ellis Peters

- The Egyptian Cat Mystery: A Rick Brant Science-Adventure Story #16 by John Blaine

- The Electronic Mind Reader: A Rick Brant Science-Adventure Story #12 by John Blaine

- Ember Falls by S. D. Smith

- An Excellent Mystery (Brother Cadfael #11) by Ellis Peters

- The First Fowler by S. D. Smith

- The Flaming Mountain: A Rick Brant Science-Adventure Story #17 by John Blaine

- The Flying Stingaree: A Rick Brant Science-Adventure Story #18 by John Blaine

- Go Wild by John Ratey and Richard Manning

- The Golden Skull: A Rick Brant Science-Adventure Story #10 by John Blaine

- The Great Divorce by C. S. Lewis

- The Green Ember by S.D. Smith

- The Hermit of Eyton Forest (Brother Cadfael #14) by Ellis Peters

- Innovation on Tap by Eric B. Schultz

- The Last Archer by S. D. Smith

- The Leper of Saint Giles (Brother Cadfael #5) by Ellis Peters

- The Lost City: A Rick Brant Science-Adventure Story #2 by John Blaine

- Lost in Math: How Beauty Leads Physics Astray by Sabine Hossenfelder

- The Magic Talisman: A Rick Brant Science-Adventure Story #24 by John Blaine

- Mere Christianity by C. S. Lewis

- Miracles by C. S. Lewis

- The Misadventured Summer of Tumbleweed Thompson by Glenn McCarty

- Monk's Hood (Brother Cadfael #3) by Ellis Peters

- A Morbid Taste for Bones (Brother Cadfael #1) by Ellis Peters

- More Sex Is Safer Sex: The Unconventional Wisdom of Economics by Steven E. Landsburg

- Ocean-Born Mary by Lois Lenski

- On Stories: And Other Essays on Literature by C. S. Lewis

- One Corpse Too Many (Brother Cadfael #2) by Ellis Peters

- Ordinary Grace by William Kent Krueger

- Past Watchful Dragons: The Narnian Chronicles of C. S. Lewis by Walter Hooper

- Perelandra (space trilogy part 2) by C. S. Lewis

- The Phantom Shark: A Rick Brant Science-Adventure Story #6 by John Blaine

- The Pilgrim of Hate (Brother Cadfael #10) by Ellis Peters

- The Pirates of Shan: A Rick Brant Science-Adventure Story #14 by John Blaine

- Poems by C. S. Lewis

- A Preface to "Paradise Lost" by C. S. Lewis

- A Rare Benedictine: The Advent of Brother Cadfael (Brother Cadfael #16) by Ellis Peters

- The Raven in the Foregate (Brother Cadfael #12) by Ellis Peters

- Recasting the Past: The Middle Ages in Young Adult Literature by Rebecca Barnhouse

- Reflections on the Psalms by C. S. Lewis

- The Rithmatist by Brandon Sanderson

- Rocket Jumper: A Rick Brant Science-Adventure Story #21 by John Blaine

- The Rocket's Shadow: A Rick Brant Science-Adventure Story #1 by John Blaine

- The Rose Rent (Brother Cadfael #13) by Ellis Peters

- The Ruby Ray Mystery: A Rick Brant Science-Adventure Story #19 by John Blaine

- Saint Peter's Fair (Brother Cadfael #4) by Ellis Peters

- The Sanctuary Sparrow (Brother Cadfael #7) by Ellis Peters

- The Scarlet Lake Mystery: A Rick Brant Science-Adventure Story #13 by John Blaine

- The Screwtape Letters and Screwtape Proposes a Toast by C. S. Lewis

- Sea Gold: A Rick Brant Science-Adventure Story #3 by John Blaine

- Smoke on the Mountain by Joy Davidman

- Smugglers' Reef: A Rick Brant Science-Adventure Story #7 by John Blaine

- Son of Charlemagne by Barbara Willard

- Stairway to Danger: A Rick Brant Science-Adventure Story #9 by John Blaine

- The Story of Christianity, Volume 1: The Early Church To The Dawn Of The Reformation by Justo L. Gonzalez

- The Story of Christianity, Volume 2: The Reformation to the Present Day by Justo L. Gonzalez

- Strange Planet by Nathan W. Pyle

- Studies in Words by C. S. Lewis

- Surprised by Joy by C. S. Lewis

- That Hideous Strength (space trilogy part 3) by C. S. Lewis

- Till We Have Faces by C. S. Lewis

- The Veiled Raiders: A Rick Brant Science-Adventure Story #20 by John Blaine

- The Virgin in the Ice (Brother Cadfael #6) by Ellis Peters

- The Wailing Octopus: A Rick Brant Science-Adventure Story #11 by John Blaine

- The Weight of Glory and other Addresses by C. S. Lewis

- The Whispering Box Mystery: A Rick Brant Science-Adventure Story #5 by John Blaine

- The Wreck and Rise of Whitson Mariner by S. D. Smith

The following quotation is from C. S. Lewis's Studies in Words. It's not a book aimed at the hoi polloi—those of us without a strong background in classical literature, Latin, Greek, French, and whatever else scholars were supposed to know in his day. So do not even try to understand it all, stripped as it is of its context and what has been said on previous pages. It's not hard to follow the point of the sentence I have bolded, however.

Distinct from this, so far as I can see, is the use of communis sensus as the name of a social virtue. Communis (open, unbarred, to be shared) can mean friendly, affable, sympathetic. Hence communis sensus is the quality of the "good mixer," courtesy, clubbableness, even fellow-feeling. Quintilian says it is better to send a boy to school than to have a private tutor for him at home; for if he is kept away from the herd (congressus) how will he ever learn that sensus which we call Communis? (p. 146)

If you want to poke the bear at any gathering of homeschoolers, ask the question, "But what about socialization?"

We have to be careful because this can be an innocent, serious inquiry that deserves a serious answer. The above is not suggested as the best way to respond, no matter how tempting. But we get so very, very tired of the question, perhaps in the same way that parents of large families get tired of being asked, "Haven't you figured out what causes that?" Large families who homeschool get both, of course.

I'll spare you the numerous studies and writings—and comics—that make the point that homeschooling is an excellent vehicle for helping children learn to get along well with others and to engage wisely with society in general. You can Google that for yourself.

But Quintilian (c. 35 - c. 100 AD) proves that the question is nearly as old as the Roman hills. Then again, he was a teacher with his own public school, and a lawyer as well, so perhaps he was a bit biased.

Our Church History class has resumed: we have moved on to Volume 2 of Justo L. Gonzales' The Story of Christianity. The books are interesting and the class even better—it's helpful to have our well-educated pastor's insights to affirm/debunk/clarify/expand the author's views. I wish there were more discussion—but the class is already an hour and a half long.

I recently rediscovered this cartoon, which I first came upon in 2012. Sometimes it feels like a good summary of church history. Or the history of science, for that matter. Or the human condition in general! (Click image to enlarge.)

Recasting the Past: The Middle Ages in Young Adult Literature by Rebecca Barnhouse (Boynton/Cook, 2000)

Recasting the Past: The Middle Ages in Young Adult Literature by Rebecca Barnhouse (Boynton/Cook, 2000)

This was another book from my son-in-law's wish list that I found intriguing. It turned out to be both disappointing and enlightening.

The disappointment was my own fault: The stated purpose of the book is "to provide teachers, librarians, and scholars of adolescent literature with a discussion of fiction set in the Middle Ages," so I should not have been surprised that the author talks like an educationist. Neither should I have been surprised (though I was) that the books she analyzes are all very modern. It reminds me of the fifth grade teacher who required that during their "free reading time," her students read only books from the Sunshine State Young Readers Awards list. This, she assured me, was because she wanted to make sure the children were reading quality books. Once I discovered that even to be nominated for that list a book had to be fiction and published withing the last three years, I knew why I was far less than impressed with the selection. I suppose modern authors need some support, but inflicting their works—to the exclusion of all others—on helpless students is even more unfair than forcing the students to eat school lunches.

This teacher-orientation and modern-author bias of Recasting the Past got my reading off on the wrong foot, but I was able to get over it because there really is some good information here. I've long known that much historical fiction, particularly for some reason that favored by schools (and popular movies), plays fast and loose with the facts. I figured the blame mainly fell on lazy authors, who had a story to tell and liked the idea of fitting it into an historical time period, but preferred to make the time fit the story rather than the other way around. Barnhouse opened my eyes to an entirely different source for the problem.

Although the author does not acknowledge this, I'm convinced that the base culprit is that there is such as thing as "young adult fiction." Why there should be is beyond my ken. Anyone who is mature enough to handle the subjects dealt with in these books—which include torture, religious doubts, and sexual activity—should be offended by dumbed-down reading levels and the assumption that everyone of a certain age must be interested in the same things.

Be that as it may, these are aimed at a young adult audience, and it shows. First and worst, the authors are apparently viewing their stories primarily as vehicles for teaching, and teaching 21st century values more than teaching history.

One such value is literacy. Barnhouse notes that much historical fiction aimed at schoolchildren is anachronistic in its attitude towards reading, writing, and book learning. No doubt they want to encourage the same in their modern readers, but it is wrong to give the impression that back then books were considered the key to knowledge, ignoring the practical ways knowledge was passed on in those times.

Modern authors also seem uncomfortable with allowing their young readers to experience attitudes not in line with 21st century standards. The young protagonists must be models of tolerance and diversity as defined by modern educationists; if anything negative is said about Jews, for example, it must come from the mouth of a character that the readers are not likely to like or respect. In a similarly unrealistic approach, Jews, Muslims, and generally anyone-but-Christians are treated by authors of much young adult fiction as paragons of virtue, instead of as human beings.

Barnhouse touches on other subjects, including stories that appear to be set in medieval times but actually belong in the Fantasy genre.

The primary use of his short book is for developing some tools for recognizing anachronism in so-called young adult fiction. Perhaps the most important of these tools is simply being aware of the problem.

Just two short quotes this time, emphasis mine:

The words "Middle Ages" imply a time between two eras, the Roman Empire and the rebirth of Roman culture in the Italian Renaissance. However, tell a twelfth-century Parisian scholar like Peter Abelard that Roman learning is dead and you'll get a surprised look—that is, if you can pry him away from his study of Greek and Roman historians and philosophers. Abelard and his contemporaries used the word modern to describe themselves. The big lie perpetrated by the Renaissance Italians, who said everything was dark and barbaric until they reinvented Rome, shows how little they knew about the transmission of thought, culture, and learning in the medieval period. While it's true that the vast majority of people didn't participate in all of this learning, neither did the majority of Romans. (Introduction, p xiii)

Well-told modern tales of the Middle Ages abound. ... The writers who research carefully enough to understand the differences between medieval and modern attitudes, between different medieval settings, and between fantasy and history, can help their readers understand a strange and distant culture: the Middle Ages. Writers who create memorable, sympathetic characters who retain authentically medieval values teach their audience more than those who condescend to readers by sanitizing the past. Trusting readers to comprehend cultural differences, presenting the Middle Ages accurately, and telling a good story results in compelling historical fiction, fiction that, like medieval literature in its ideal form, teaches as it delights. (p 86)

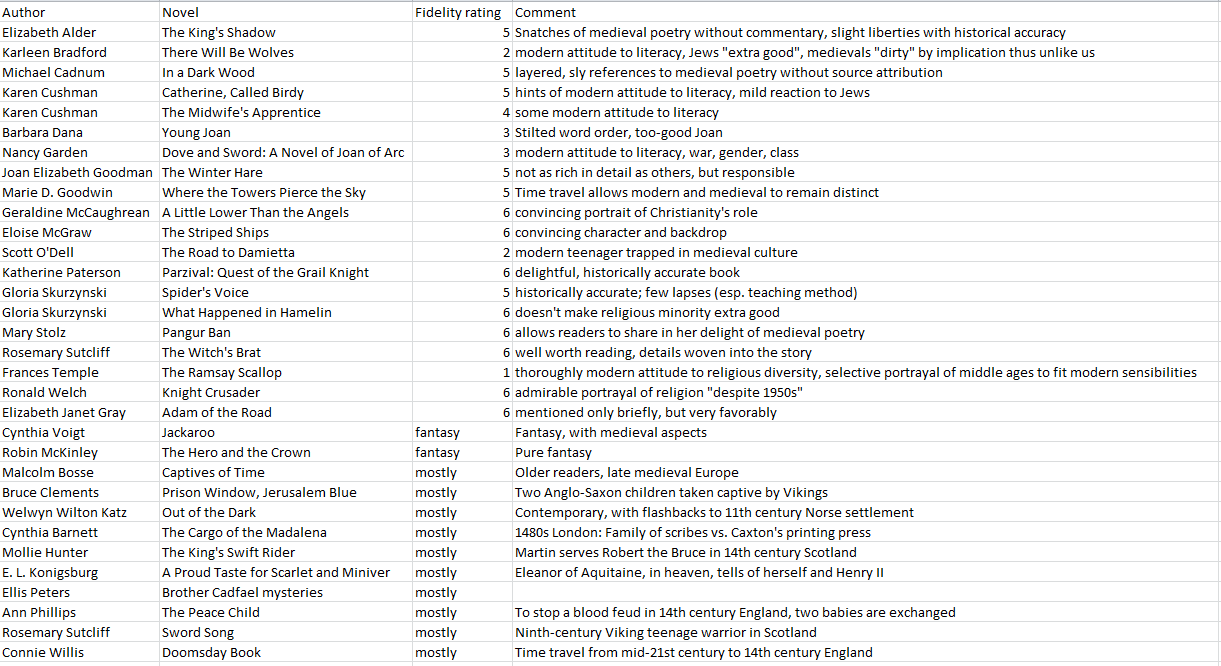

UPDATE 11/5/19 Here's a table from Stephan, summarizing the book's evaluations. Click to enlarge.

Stephan says, What might be confusing about the table is the multiple use of the comments column. The first books with a fidelity rating > 0 come with comments that summarize very briefly Mrs Barnhouse‘s critique; those with a rating = 0 with a „fantasy level“ comment; and the rest with a summary.