At the recent mall shooting in Greenwood, Indiana, the law enforcement response was well-trained and fast. But what kept this event from being far more tragic was a 22-year-old already on the scene and apparently sufficiently observant, calm, trained, and equipped to stop the carnage almost immediately by taking out the gunman. As Greenwood police chief Jim Ison himself said, "The real hero of the day is the citizen that was lawfully carrying a firearm in that food court and was able to stop the shooter almost as soon as he began."

Once upon a time, 22-year-olds were accustomed to doing the work of adults, managing their own families, farms, and often businesses. As I'm fond of reminding people, the famed Admiral David Farragut took command of a captured British ship in the War of 1812 at the age of 11, and was given his first command of a U. S. Navy ship at 21. With training, experience, opportunity, and higher expectations, our young people can be far more competent at life that we usually give them credit for.

[This post was originally entitled, "Camouflage"; I've now changed that to make it part of my "YouTube Channel Discoveries" series.]

Here's another YouTube channel we've been enjoying: Chris Cappy's Task and Purpose. How on earth could I enjoy videos about military tactics, strategy, history, and weapons? Here's a quote from the channel's About section:

Chris Cappy the host is a former us army infantryman and Iraq Veteran. This YouTube channel is a forum for all things military. From historical information to the latest news on weapons programs. We discuss all these details from the veteran's perspective. The first priority with our videos is to be entertaining.

I guess it's the last sentence. Chris Cappy is knowledgeable and entertaining. He may bill himself as "your average infantryman," but he's not your average military college professor droning on in the front of an auditorium filled with bored students.

The video that hooked me is the one below, How Camouflage Evolved (15 minutes). I'm certain we have grandchildren who would find it as enjoyable as I did.

Permalink | Read 2177 times | Comments (0)

Category Reviews: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Education: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Random Musings: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Just for Fun: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] YouTube Channel Discoveries: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

When our kids were in school, individual learning styles were becoming a big thing. They were each given a test that supposedly categorized them as Visual, Auditory, or Kinesthetic learners. We could see some truth in the results, though the skeptic in me wasn't sure it had any more basis in reality than finding some truth in the Chinese Zodiac descriptions you see on the placemats in cheap Chinese restaurants.

Here's a presentation that agrees with my cynical view (15 minutes):

The contrast between the enormous popularity of the learning styles approach within education, and the lack of credible evidence for its utility is, in our opinion, striking and disturbing.

There's a large body of literature that supports the claim that everyone learns better with multi-modal approaches, where words and pictures are presented together, rather than either words or pictures alone.

Ultimately, the most important thing for learning is not the way the information is presented, but what is happening inside the learner's head. People learn best when they're actively thinking about the material, solving problems, or imagining what happens if different variables change.

I call this just another bit of evidence for the harm we do when we label people. You're a kinesthetic learner, she has ADHD, he's "on the spectrum," I suffer from face blindness.... Sometimes labels can help us understand ourselves better, but more often they encourage us (and our parents, teachers, employers) to shut ourselves up in boxes and put limits on our abilities.

My constant prayer during Pandemic-tide has been that we would learn to think outside our traditional, largely unquestioned, boxes of life. And so we have.

Many more workers—and their employers—have discovered that remote work can be a good thing. This is not new; back in the day we called it "telecommuting" and it came with both blessings (work from anywhere at any time) and curses (work from everywhere all the time). But, thanks to the pandemic restrictions, the number of people exercising this option has grown to where it's having a significant effect on the demographics of the country. Just ask the citizens of New Hampshire, whose real estate prices have been driven through the roof by pressure from Boston- and New York City-dwellers who no longer need to live in an expensive city to work there. Again: blessings and curses.

More exciting to me is the surge in home education.

A friend sent me this Associated Press article from mid-April, confirming what I've been hearing elsewhere: Homeschooling Surge Continues Despite Schools Reopening.

The coronavirus pandemic ushered in what may be the most rapid rise in homeschooling the U.S. has ever seen. Two years later, even after schools reopened and vaccines became widely available, many parents have chosen to continue directing their children’s educations themselves.

Families that may have turned to homeschooling as an alternative to hastily assembled remote learning plans have stuck with it—reasons include health concerns, disagreement with school policies and a desire to keep what has worked for their children.

[A Buffalo, New York mother] says her children are never going back to traditional school. Unimpressed with the lessons offered remotely when schools abruptly closed their doors in spring 2020, she began homeschooling her then fifth- and seventh-grade children that fall. [She] had been working as a teacher’s aide [and] knew she could do better herself. She said her children have thrived with lessons tailored to their interests, learning styles and schedules.

Once a relatively rare practice chosen most often for reasons related to instruction on religion, homeschooling grew rapidly in popularity following the turn of the century before [it] leveled off at around 3.3%, or about 2 million students, in the years before the pandemic, according to the Census. Surveys have indicated factors including dissatisfaction with neighborhood schools, concerns about school environment and the appeal of customizing an education.

As usual, even a good article gets some things wrong. Home education is no new phenomenon, but as old as the hills. Abraham Lincoln was just one of many homeschooled presidents, though in those days they called it "self-educated." And for a very long time it had nothing in particular to do with reasons of religion. Children were home-educated by necessity (schools unavailable, or children needed at home, e.g. Lincoln), because of an intellectual mismatch between child and school (e.g. Thomas Edison, Albert Einstein), because the atmosphere and philosophies of the schools differed significantly from those of the parents (sometimes associated with a particular religion, sometimes not), or simply because parents and/or children were dissatisfied with what the schools had to offer. In the last quarter of the 20th century, it is true, homeschooling ranks were swelled by Evangelical Christians who had discovered that the Amish were right: home education could meet their needs better than public or even Christian schools. This raised the public's awareness of an educational phenomenon whose adherents had mostly been trying to fly under the radar, and led to home education's establishment as a valid and legal educational approach—at least in the United States. This new familiarity—nearly everyone now knew a homeschooling family—opened the field to many others, with varied reasons for their choices.

The proportion of Black families homeschooling their children increased by five times, from 3.3% to 16.1%, from spring 2020 to the fall, while the proportion about doubled across other groups. [emphasis mine] ...

“I think a lot of Black families realized that when we had to go to remote learning, they realized exactly what was being taught. And a lot of that doesn’t involve us,” said [a mother from Raleigh, North Carolina], who decided to homeschool her 7-, 10- and 11-year-old children. “My kids have a lot of questions about different things. I’m like, ‘Didn’t you learn that in school?’ They’re like, ‘No.’”

[The mother from Buffalo] said it was a combination of everything, with the pandemic compounding the misgivings she had already held about the public school system, including her philosophical differences over the need for vaccine and mask mandates and academic priorities. The pandemic, she said, “was kind of—they say the straw that broke the camel’s back—but the camel’s back was probably already broken.”

I find it especially exciting that minorities are discovering that they are not locked by their circumstances into an educational system that is not meeting their needs. The pandemic restrictions have given families of all descriptions the opportunity to taste educational freedom*, and many, having made that leap unwillingly, have chosen to stick with it.

Choice is the thing. If the great relief expressed by many parents at the re-opening of schools is any indication, I'd say that home education is unlikely to become a majority educational philosophy in America. But it works so well for so many families, including those who opt for different educational choices at different times in their lives—we ourselves made use of public, private, and home education at one time or another—that I'm thrilled to see homeschooling on the rise all over the country, and even the world.

Our established educational system is understandably threatened by any challenge to its power. (Nonetheless, we had many teachers who cheered on our own homeschooling efforts.) But powerful monopolies—in education as well as government, medicine, transportation, information, and all other essential services—are dangerous, even to themselves. Healthy competition can only make our public education better.

One new homeschooling mother summed it up well:

It’s just a whole new world that is a much better world for us.

*I realize that many homeschoolers are cringing at the idea that the at-home learning offered by schools (public and private) during the pandemic bore any resemblance to the true freedom of home education, since it usually attempted to replicate as much as possible the restrictions inherent in formal, mass instruction. Nonetheless, it opened eyes ... and doors.

Everybody in our family goes to college. That was true for us, our parents, some of our grandparents, even a few great-grandparents and beyond, plus our children, our siblings and most of their spouses, and our siblings' children and their spouses. We assumed that legacy would continue through our grandchildren.

So why am I thrilled that our oldest grandchild has chosen to eschew college in favor of a four-year apprenticeship as an electrician? For several reasons.

- Colleges and universities are still recovering from COVID disruptions. Many have onerous vaccination policies, and less-than-stellar online courses. Things are getting better, I'm sure, but it seems like a good time to wait for a bit more stability.

- His intellectual curiosity and ability are undiminished, and his unconventional home education has made him adept at learning whatever he wants to learn, using a variety of means. His memory and his breadth of knowledge are impressive. If someday he decides he wants to learn what college can best teach, I'm confident he'll manage well.

- In the meantime, he's getting paid for his education, instead of accumulating debt.

- He should come through his apprenticeship with practical skills that will generate a solid income and enable him to pursue other interests (e.g. music) without worrying about making a living from them.

- What's more, those practical skills will be portable—electricians are needed everywhere—and very unlikely to be outsourced to foreign countries, as so many of my college-educated generation's jobs have been.

However, all this does not mean I've given up on college educations. We have other grandchildren, most too young to think about careers, but the two next oldest are leaning towards plans that would most likely require more traditional higher education.

There is, of course, another problem: the poisonous ethical, philosophical, and political atmosphere that now rules at most colleges and universities. It was bad enough when we were in school, worse in our children's time, and from everything I hear, unbelievably rancid and dangerous today. I remember reading an article decades ago about a disastrous college experience; the title was something like, "I Paid $50,000 a Year to Send My Daughter to Hell." As far as I can tell, today the levels of hell are much deeper and the price tag a lot higher. It doesn't surprise me that some people are actively encouraging their children to avoid college.

That's why I was happy to run into a couple of college professors who acknowledge the problems but encourage us not to abandon academia altogether. Both videos work from the point of view of conservative students facing the intense pressures of life at left-leaning universities, but really the advice is excellent for fish-out-of-water students of any kind.

This 3-minute video is an excerpt of a larger one. The original (20 minutes) is here.

This one's even better (5 minutes).

Here's my personal favorite of his suggestions:

Work hard. College faculty value hardworking, enthusiastic students. Period. The easiest way to win over your leftist professor is to do your classwork in a conscientious manner. That's your way of showing respect. Many teachers will respect you in turn. If you read the assigned materials, take part in class discussion, and show that you understand the key concepts, chances are you'll do just fine.

That's good advice for any student. Or employee, for that matter.

I'm solidly in favor of alternatives to college, and opposed to the bizarre idea that "everyone deserves a college education." I'm equally opposed to completely deserting the ship of academia, no matter how much it may seem to be sinking. As in so many other things, it all comes down to what's best for each individual student, and not locking anyone into a particular path.

My brother graduated from Oberlin College, which automatically gave it a place in my heart—well, that and the amazing Gibson's doughnuts he'd bring with him when he came home on vacation.

When our daughter was interviewing at colleges, the shine came off Oberlin a bit. The school openly bragged about its "progressive" reputation, but to my surprise we found it to be the least open-minded of all the schools any of our children had visited—especially when it came to home education. Every other college was happy to accept homeschooled students, but Oberlin was clearly reactionary and suspicious, putting up the most onerous barriers to their acceptance. But she chose to go elsewhere for other reasons, so I chose to remember Oberlin for the doughnuts.

Recently, however, I heard news of an incident that began over five years ago and is still dragging on, shaking my respect to the core. Probably I shouldn't be too hard on Oberlin, as my own alma mater disillusioned me years ago. But in this case, Gibson's Bakery is involved. Colleges have gotten away with many terrible things, but let them mess with good doughnuts, and I must speak up.

The excerpts below are from the relevant Wikipedia article. I know Wikipedia is hardly the most reliable source, and has its biases, but I chose it because of all the articles I read, its was the most positive toward the college.

The beginning, November 2016

An underage African-American Oberlin College student ... attempted to purchase a bottle of wine using a fake identification card. The store clerk, Allyn D. Gibson ... rejected the fake ID. Gibson noticed that the student was concealing two other bottles of wine inside his jacket. According to a police report, Gibson told the student he was contacting the police, and when Gibson pulled out his phone to take a photo of the student, the student slapped it away, striking Gibson's face. The student ran out of the store. Gibson followed and then grabbed and held onto the shoplifter outside the store after the shoplifter had also assaulted the store owner.... Two other students ... friends of the shoplifter, joined the scuffle. When the police arrived, they witnessed Gibson lying on the ground with the three students punching and kicking him. The police report stated that Gibson sustained a swollen lip, several cuts, and other minor injuries. The police arrested the students, charging all three with assault and the shoplifter with robbery as well. In August 2017, the three students pleaded guilty, stating that they believed Gibson's actions were justified and were not racially motivated. Their plea deals carried no jail time in exchange for restitution, the public statement, and a promise of future good behavior.

Oberlin's actions

Of course the college responded to the incident by disciplining the students involved, right? Not a chance. Students, faculty, and administrators united to attack the store.

The day after the incident, faculty and hundreds of students gathered in a park across the street from Gibson's Bakery protesting what they saw as racial profiling and excessive use of force by Gibson toward the shoplifter. The Oberlin Student Senate immediately passed a resolution saying that the bakery "has a history of racial profiling and discriminatory treatment of students and residents alike," calling for all students to "immediately cease all support, financial and otherwise, of Gibson's," and called upon Oberlin College President Marvin Krislov to publicly condemn the bakery. For about two months, the college suspended its purchasing agreement with the bakery for the school's dining halls....

Oberlin blamed the bakery for bringing the protests on itself, claiming that "Gibson bakery's archaic chase-and-detain policy regarding suspected shoplifters was the catalyst for the protests...."

The following, apparently, is what the college thinks should be done with students who steal:

Oberlin made a proposal to all local businesses that if a business would contact the college instead of the police when students were caught shoplifting, the college would advise the students that if caught shoplifting a second time they would face legal charges.

There's more, and worse. I went to college in the early 1970's; I know that students, and even faculty, can do some pretty stupid things. But in my day the administrators were a little more sane and stable.

The other side of the story

Local police records showed no previous accusations of racial profiling by Gibson's Bakery. Of the forty adults arrested for shoplifting from the bakery in a five-year period, only six were black. As a part of the three students' guilty plea in August 2017, each read a statement saying, "I believe the employees of Gibson’s actions were not racially motivated. They were merely trying to prevent an underage sale." Reporters obtained an email written by ... an employee for the school's communications department, telling her bosses that she found the protests "very disturbing," saying, "I have talked to 15 townie friends who are [persons of color] and they're disgusted and embarrassed by the protest. In their view, the kid was breaking the law, period... To them this is not a race issue at all." During the trial ... a black man who worked his way through technical college while working at Gibson’s Bakery testified that the racist allegations against his former employer were untrue. "In my life, I have been a marginalized person, so I know what it feels like to be called something that you know you’re not. I could feel his pain. I knew where he was coming from." ... [A] black man, employed at Gibson's since 2013, testified that he had observed no racist treatment of customers or employees. "Never, not even a hint. Zero reason to believe, zero evidence of that."

The latest judicial ruling

On April 1, 2022, the Ninth Ohio District Court of Appeals dismissed Oberlin College's appeal. In a 3-0 decision, the panel upheld the jury verdict that Oberlin College defamed, inflicted distress, and illegally interfered with the bakery. The damages were capped by Ohio state law at $25 million in total damages, in place of the jury's original verdict of $11.1 million in compensatory and $33.2 million in punitive damages. Oberlin was also ordered to pay $6.3 million in attorney's fees to the bakery.

Oberlin is still refusing to pay what they owe, and two of the owners of Gibson's Bakery have died awaiting justice.

Milestone note: This is my 3000th blog post. That calls for something serious, but not depressing. Here you go:

Fairy tales ... are not responsible for producing in children fear, or any of the shapes of fear; fairy tales do not give the child the idea of the evil or the ugly; that is in the child already, because it is in the world already. Fairy tales do not give the child his first idea of bogey. What fairy tales give the child is his first clear idea of the possible defeat of bogey. The baby has known the dragon intimately ever since he had an imagination. What the fairy tale provides for him is a St. George to kill the dragon. — G. K. Chesterton, 1909 ("The Red Angel")

Since it is so likely that [children] will meet cruel enemies, let them at least have heard of brave knights and heroic courage. ... Let there be wicked kings and beheadings, battles and dungeons, giants and dragons, and let the villains be soundly killed at the end of the book. — C. S. Lewis, 1952 ("On Three Ways of Writing for Children")

I write stories for courageous kids who know that dragons are real, that they are evil, and that they must be defeated. I don’t do that because I want to hurt children, but because children do and will face hurts every day. I don’t want to expose them to evil, I want to help them become people for whom evil is an enemy to be exposed. I want to tell them dangerous stories so that they themselves will become dangerous—dangerous to the darkness. — S. D. Smith, 2022 ("My Blood for Yours")

Smith's essay in video form (three minutes).

P.S. There's a new Green Ember book to be released soon, Prince Lander and the Dragon War. Time to reread the previous books in preparation!

It's time for my annual compilation of books read during the past year.

- Total books: 85

- Fiction: 66

- Non-fiction: 19

- Months with most books: a tie between July and September (12)

- Month with fewest books: April (2)

- Most frequent authors: Randall Garrett (19), Lois Lenski (16), Tony Hillerman (10), Brandon Sanderson (7). Hillerman is the only author to make the top four both last year and this, as his excellent Leaphorn & Chee books spanned the two years. Garrett and Lenski made such a strong showing because they were each the subject of a particular focus, and their books are generally short. Sanderson, on the other hand, though he's only represented by seven books, is the runaway leader in number of pages.

Here's the list, grouped by author; links are to reviews. The different colors only reflect whether or not you've followed a hyperlink. The ratings (★) and warnings (☢) are on a scale from 1 to 5, with 1 being the lowest/mildest. Warnings, like the ratings, are highly subjective and reflect context, perceived intended audience, and my own biases. Nor are they completely consistent. They may be for sexual content, language, violence, worldview, or anything else that I find objectionable. Your mileage may vary.

| Title | Author | Rating/Warning |

| Matthew Wolfe 2: The Adventures Begin | Blair Bancroft (Grace Kone) | ★★★ ☢ |

| Matthew Wolfe 3: Revelations | Blair Bancroft (Grace Kone) | ★★★ |

| The Art of Evil | Blair Bancroft (Grace Kone) | ★★★★ ☢ |

| Mistborn 1: The Final Empire | Brandon Sanderson | ★★★ |

| Mistborn 2: The Well of Ascension | Brandon Sanderson | ★★★ |

| Mistborn 3: The Hero of Ages | Brandon Sanderson | ★★★ |

| Stormlight 1: The Way of Kings | Brandon Sanderson | ★★★ |

| Stormlight 2: Words of Radiance | Brandon Sanderson | ★★★★ |

| Stormlight 2.5: Edgedancer | Brandon Sanderson | ★★★★★ |

| Warbreaker | Brandon Sanderson | ★★★★ |

| Deep Work | Cal Newport | ★★★★★ |

| So Good They Can't Ignore You | Cal Newport | ★★★★★ |

| Rosefire | Carolyn Clare Givens | ★★★ |

| A Child's History of England | Charles Dickens | ★★★ ☢ |

| The Light in the Forest | Conrad Richter | ★★ |

| Just David (aka North to Freedom) | Eleanor Porter | ★★★★ |

| Just David (read a second time to check for differences between the original and the modern editions) | Eleanor Porter | ★★★★ |

| Brian's Saga 1: Hatchet | Gary Paulsen | ★★★ ☢ |

| Brian's Saga 2: The River | Gary Paulsen | ★★★ ☢ |

| Brian's Saga 3: Brian's Winter | Gary Paulsen | ★★★ ☢ |

| Brian's Saga 4: Brian's Hunt | Gary Paulsen | ★★ ☢☢ |

| Brian's Saga 4: Brian's Return | Gary Paulsen | ★★ ☢ |

| Why Good Arguments Often Fail | James W. Sire | ★★★★ |

| Discipline Equals Freedom: Field Manual | Jocko Willink | ★ |

| Extending the Table: A World Community Cookbook | Joetta Handrich Schlabach | ★★ |

| Greenglass House | Kate Milford | ★★★ |

| Kisses from Katie | Katie Davis with Beth Clark | ★★★ |

| Bayou Suzette | Lois Lenski | ★★★★ |

| Blue Ridge Billy | Lois Lenski | ★★★★ |

| Boom Town Boy | Lois Lenski | ★★★★ |

| Coal Camp Girl | Lois Lenski | ★★★★ |

| Corn Farm Boy | Lois Lenski | ★★★★ |

| Deer Valley Girl | Lois Lenski | ★★★ |

| Flood Friday | Lois Lenski | ★★★★ |

| Houseboat Girl | Lois Lenski | ★★★★ |

| Indian Captive | Lois Lenski | ★★★★ |

| Judy's Journey | Lois Lenski | ★★★★ |

| Mama Hattie's Girl | Lois Lenski | ★★★★ |

| Prairie School | Lois Lenski | ★★★★ |

| San Francisco Boy | Lois Lenski | ★★★★ |

| Shoo-Fly Girl | Lois Lenski | ★★★ |

| Strawberry Girl | Lois Lenski | ★★★★ |

| Texas Tomboy | Lois Lenski | ★★★★ |

| Out of This World | Lowell Thomas, Jr. | ★★★★ |

| Talking to Strangers | Malcolm Gladwell | ★★★★ |

| Humble Pi | Matt Parker | ★★★★ |

| In the Heart of the Sea | Nathaniel Philbrick | ★★★ ☢ |

| The Wild Robot | Peter Brown | ★★★★ |

| The Wild Robot Escapes | Peter Brown | ★★★★ |

| A Spaceship Named McGuire | Randall Garrett | ★★★ |

| Anything You Can Do | Randall Garrett | ★★★ |

| But, I Don't Think | Randall Garrett | ★ |

| By Proxy | Randall Garrett | ★★★ |

| Cum Grano Salis | Randall Garrett | ★★★★ |

| Damned If You Don't | Randall Garrett | ★★★ |

| Despoilers of the Golden Empire | Randall Garrett | ★★★ |

| His Master's Voice | Randall Garrett | ★★★ |

| Nor Iron Bars a Cage | Randall Garrett | ★★★ |

| Or Your Money Back | Randall Garrett | ★★★ |

| Pagan Passions | Randall Garrett | ★★ ☢☢ |

| Psi-Power 1: Brain Twister | Randall Garrett | ★★★ |

| Psi-Power 2: The Impossibles | Randall Garrett | ★★★ |

| Psi-Power 3: Supermind | Randall Garrett | ★★ |

| Quest of the Golden Ape | Randall Garrett | ★★ |

| The Eyes Have It | Randall Garrett | ★★★★ |

| The Foreign Hand-Tie | Randall Garrett | ★★★ |

| The Highest Treason | Randall Garrett | ★★★ |

| The Penal Cluster | Randall Garrett | ★★ |

| Loserthink | Scott Adams | ★★★ |

| Life of Fred: Pre-Algebra 0 with Physics | Stanley F. Schmidt | ★★★★ |

| Life of Fred: Australia | Stanley F. Schmidt | ★★★★ |

| Life of Fred: Pre-Algebra 2 with Economics | Stanley F. Schmidt | ★★★★ |

| Life of Fred: Trigonometry Expanded Edition | Stanley F. Schmidt | ★★★★ |

| Coyote Waits | Tony Hillerman | ★★★ |

| Hunting Badger | Tony Hillerman | ★★★ |

| Sacred Clowns | Tony Hillerman | ★★★ |

| Skeleton Man | Tony Hillerman | ★★★ |

| Skinwalkers | Tony Hillerman | ★★★ |

| The Dark Wind | Tony Hillerman | ★★★ |

| The Ghostway | Tony Hillerman | ★★★ |

| The People of Darkness | Tony Hillerman | ★★★ |

| The Shape Shifter | Tony Hillerman | ★★★ |

| The Wailing Wind | Tony Hillerman | ★★★ |

| The Bible (English Standard Version, canonical) | ★★★★★ | |

| The New Testament (King James Version, canonical) | ★★★★★ |

It's been a month since I linked to a Viva Frei "Sidebar" video, more because there's been too much to choose from than than too little! This one is a two-hour long interview with Blake Masters. As with most of their Sidebar guests, I'd never heard of him, but if he wins in his attempt to become a U. S. senator from Arizona, I may learn more about him. Or if one of our grandchildren wins a Thiel Fellowship....

Blake Masters is president of the Thiel Foundation and the Fellowhip is their flagship program. He talks about it briefly during the interview, from about 32:32 to 41:56. The following video should start close to that point; you'll have to stop it yourself as a quick search did not show me an easy way to accomplish that automatically. The rest of the interview is also interesting, but who has two hours to listen to it?

Basically, the foundation believes that too many people are going to college, and funds efforts to do something productive without it. As Masters puts it, "We pay young people to drop out of college." About 10% of the fellowship recipients eventually go back to school, mostly for engineering degrees or other practical majors. MIT has even been known to hold students' places open for them.

Masters has some other good suggestions for taming the massive quagmire that higher education has become. One of them has long been a favorite of my husband's: find a way to make colleges have "skin in the game" of student loans. Right now they have every incentive to push students toward massive, unmanageable debt, and no incentive not to. (Professor friends, please don't stop the video in disgust when Viva suggests that college professors are the ones benefitting from the out-of-control costs—Masters immediately corrects him on that point.)

Masters has several other interesting things to say—the interview covers a lot—but nothing as easy to pull out separately as the above. If you have two hours you can spare to listen—there's no need to watch—go for it. Warning: the language is sometimes not what I would consider acceptable, though if I remember right the section about college is okay.

What was happening at the beginning of the 1960's?

I've long been a fan of Randall Garrett's Lord Darcy books, so when I found the Kindle version of Randall Garrett: The Ultimate Collection for 99 cents, I leapt at the chance to read some of his other stories. Nothing so far has come close to the Lord Darcy books in quality, but they've mostly been fun to read.

Recently I read The Highest Treason. It's short, under 23,000 words, and was originally published in the January 1961 issue of the magazine Analog Science Fact and Fiction. You can find a public domain version at Project Gutenberg.

The Highest Treason deals with a subject familiar to me, one I first encountered in Kurt Vonnegut's Harrison Bergeron, first published in October 1961, in The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction. That one is much shorter, only 2200 words, and can be found here in pdf form.

C. S. Lewis's Screwtape Proposes a Toast was next—and my favorite. You can read it here, in the December 19, 1959 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. I don't have a word count, but it is also quite short.

December 1959, January 1961, October 1961. Three stories written as the 1950's passed into the 1960's.

All three have as their premise the consequences of a culture of mediocrity, in which excellence in anything—beauty, art, sport, thinking, work, character—is abolished for the sake of making everyone "equal." There must have been something going on at that time period to make it a concern for at least three such varied authors.

What would they think today? From the demise of ability grouping in elementary schools, to "participation trophies," to branding as racist and unacceptable the idea that employment and leadership positions should be awarded on the basis of merit and accomplishment, we have come a long way down this path since 1960.

Here's hoping it doesn't take near-annihilation by space aliens—or the flames of hell—to wake us up.

Permalink | Read 1141 times | Comments (1)

Category Reviews: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Education: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Politics: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Random Musings: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

I read a lot.

Now, "a lot" is pretty much a meaningless term. Since I started keeping track in 2010, I have averaged 72.2 books per year (5.85 per month). For a scholar, that would not be much, but a pitifully small* number. However, compared with that mythical being, the average American, it's impressive, since for him it would be 12/year (mean) or 4/year (median). (I'm using the gender-neutral sense of "him," as I almost always do, but it is worth noting that women, as a group, read significantly more books than men: 14 vs. 9, 5 vs. 3 annually.)

Whatever. The point is that I like to read, and since 2010 I have kept a few statistics. The advantage of data is that it can surprise you. For example, 60% of my reading since that year has been fiction, although it feels as if that percentage is much lower. Partly that is because I like to read books recommended by or for our grandchildren, and often those books are shorter and quickly read. That's changing some now due to their growing taste for books like the one I just finished: Brandon Sanderson's 1000-page The Way of Kings.

Most likely the reason it feels as if I've read more non-fiction than I actually have is that I find it difficult to read a non-fiction book without writing a review of it, which can easily take longer than reading the book in the first place.

Take my current non-fiction book, for example: Loserthink, by Scott Adams. I have just finished reading Chapter 1, and already there are seven sticky notes festooning the pages, marking quotations I would want to include in a review. This is not a sustainable pace. Too many quotes and it becomes burdensome to copy them, even from an e-book. Moreover, I've learned that the more I include, the fewer people actually read, making it a waste of time for all of us. Often I include many of them anyway, for my own reference. But sometimes it reduces my review to little more than "read/don't read this book."

Still looking for the via media.

In the meantime, I'll get back to enjoying Loserthink. I don't like the negativity of the title, but Adams carefully explains its purpose. In short: it's not a label for people, but for unproductive ways of thinking, and short, negative labels make it easier to avoid bad things. I know from the interview with Scott Adams that I included in my Hallowe'en post that his personality can be abrasive, and I occasionally have doubts about listening to someone with well-developed skills in the art of persuasion. None of that means, however, that what he has to say won't be of much value.

So Good They Can't Ignore You: Why Skills Trump Passion in the Quest for Work You Love by Cal Newport (Business Plus, 2012)

So Good They Can't Ignore You: Why Skills Trump Passion in the Quest for Work You Love by Cal Newport (Business Plus, 2012)

I can't resist a Cal Newport book. My first was How to Be a High School Superstar (published 2010), then Digital Minimalism (2019) then Deep Work (2016). If the advice in any of them is out of date, I haven't noticed anything major.

So Good They Can't Ignore You is—like the others—both strong and weak but filled with interesting ideas that are contrary to much conventional wisdom. This time Newport tackles the "follow your passion" philosophy of choosing a career that was popular when the book was written. I don't think the appeal of that idea has lessened, despite the great number of college graduates who thought they were doing just that but ended up with unmanageable debt and a job at Starbuck's.

Much of his thesis is just what used to be called common sense: The work you choose doesn't matter nearly as much as how you approach it; focus on what you can offer the world rather than what the world can offer you; work hard; cultivate excellence. If that sounds boring and Puritanical, read the book to find out how it turns out to be the secret to having a career that's enjoyable and personally fulfilling. Newport fleshes out the ideas nicely, if sometimes a bit too repetitively, with explanation, analysis, and real-world examples.

As with Newport's other books, this one is business-oriented, making it hard to apply directly to non-business careers like homemaking and rearing a family. In fact, part of me wonders if it's possible to do what's necessary to achieve the skills he expects without neglecting other important parts of life. However, it must be noted that the really intense effort he recommends works best when one is young, and leads to far more autonomy and flexibility than standard career paths. It is good for a man to bear the yoke in his youth.

At present, the Kindle version of So Good They Can't Ignore You is currently on sale for $3.99. It's well worth the investment of your time and money, or a visit to your local library.

It was our eight-year-old grandson's first solo sail. He had passed all his dad's tests the day before, and was eager to go solo, despite the strong wind and tide, which were at least pushing him into the cove, rather than out into Long Island Sound. So off he went.

It was, indeed, a strong wind, which made the small boat difficult to control. He capsized twice, gamely righting the boat and climbing back in each time. After a while, however, his lack of ability to make progress toward home began to frustrate and frighten him. I would not have handled that situation at all well.

Instead of giving in to panic, however, he assessed the situation, and discovered a patch of reeds he could head for with full assistance of the wind and tide. That's where he went, planning to pull the boat up on land and walk back to the cottage for help. He grounded in the reeds, lowered the sail, removed the daggerboard and rudder, and began pulling the boat up onto the land.

He didn't quite get the chance to finish. Watching from the shore, determined not to interfere with his very own adventure, but ready to render assistance as needed, we finally decided that a "rescue party" might be of some use. When they arrived (by land) he had already done all that was necessary except for securing the boat. Mission (nearly) accomplished, both boy and boat safe and sound—then, and only then, did he give in to tears.

Kudos to the security guard who had stopped by to see what was going on: he could have said so many wrong things, but merely commended the boy for his courage and clear head, telling him he had done exactly the right things.

It was a much more satisfactory reaction than that of my own sailing adventure six years earlier: the panicked onlooker who called 911, the fire boat officials who told me they were under orders to "take me in," and the ambulance crew persistently ready to pounce on me as soon as I set foot on shore (but I outwaited them).

Don't panic; keep your head; make a plan and execute it. Save your emotional reaction for when the job is done. If an eight-year-old can do it, so can we.

I'm giving my computer files a much-needed spring summer cleaning, and came upon this, which I post here for my own future reference as much as anything. Unfortunately, I don't remember where it came from. The odds are it was from someone on Facebook, but that's the best I can do for now.

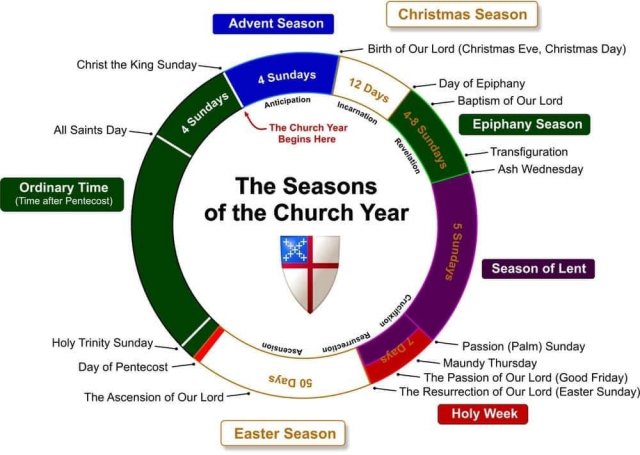

It's a clear, concise, visual guide to the seasons of the Church Year, as celebrated in the Episcopal Church and many other churches. The latter may differ in small details; I'm not familiar enough with them to say. But when I refer to the Church Year, this is what I'm talking about.

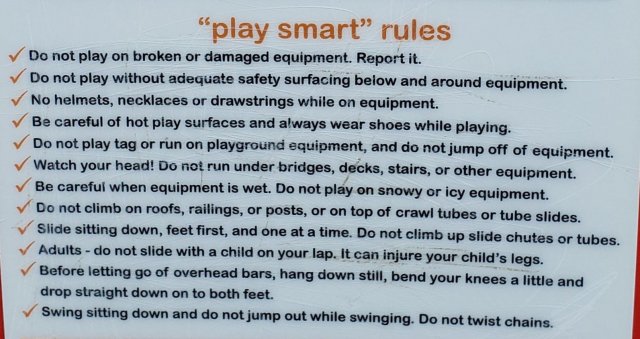

Our grandchildren's community/elementary school playground was recently updated. There was nothing obviously wrong with the old playground, which was not very old. The only obvious improvement was the addition of some equipment that could be more easily used by children with certain disabilities, which is a good thing but surely could have been accomplished without re-doing the whole thing at horrendous taxpayer expense.

Still, a playground is a playground, and this one being within walking distance for our grandchildren is a favorite destination when school is out. Everyone enjoys it, albeit on his own terms.

The first thing every one of them determined was that it was important to break every rule whenever possible. (Click to enlarge.) Beginning, of course, with the one that is not shown here: Adult supervision recommended. After all, it's only a recommendation, and we know what happened when the COVID-19 "rules" changed to "recommendations."

That gotten out of the way, it was time to notice some other interesting things about the equipment. It appears that the students at this school may grow up at a disadvantage in mathematics, at least when it comes to measurement.

I am not under five feet tall, and this is no trick of perspective. For all the money spent on this playground, couldn't they have placed the sign correctly?

On the other hand, I expect the students to have an advantage when it comes to music. How many playgrounds feature chimes in the Locrian scale?