You know I'm a big fan of Bret Weinstein and Heather Heying—the folks I call my favorite Left Coast Liberals. There's a lot we disagree about, but plenty of common ground, and I admire their dogged search for truth and willingness to follow where it leads, even if that sometimes aligns them with people they were once taught to despise.

For longer than I have known of them, YouTube has been profiting off their popular DarkHorse Podcast without remunerating them in any way. That is, YouTube "demonetized" them, which means that they can no longer get revenue from the ads YouTube attaches to their posts. The ads are still there, but YouTube takes all the profit for themselves, instead of just a percentage. (Okay, I'm aware that 100% is also a percentage; you know what I mean.) It's a dirty trick, and forces content creators to tie themselves in knots trying to avoid giving YouTube an excuse to demonetize them or to shut them down altogether. In frustration and protest, many creators have left YouTube. But that's a tough way to go, as YouTube's stranglehold as a video content platform is exceedingly strong.

One alternative that has become more and more popular is Rumble, largely because it makes a point of censoring only the most egregious content (e.g. pornography, illegal behavior) while encouraging free speech and debate, including unpopular views—such as the idea that the COVID-19 virus was originally created in the Wuhan lab during U.S.-sponsored gain-of-function research. While widely accepted now, it was not long ago that expressing such an opinion on YouTube was a fast track to oblivion.

Rumble has been steadily making improvements, but it's still not as polished and easy to use as YouTube. YouTube still has a virtual monopoly, so few content creators can afford to drop it altogether. And if your content has no political, medical, or socially-unacceptable content, it's hard to find the incentive to make the effort to switch. So I won't be boycotting YouTube any time soon.

That said, I'm glad to see that while we were out of the country, DarkHorse began moving to Rumble. Apparently they will do what many other creators have done, keeping a smaller presence on YouTube, which has by far the wider reach, while enduing Rumble with additional content. Viva Frei, for example (my favorite Canadian lawyer's site), does the first half hour or so of his podcast on both YouTube and Rumble, then invites his YouTube viewers to move to Rumble for the rest of the show. How it will eventually work out for DarkHorse I don't know yet, but for the moment, their podcasts still appear on YouTube, but the question-and-answer sessions, along with some other content, are exclusive to Rumble.

In honor of DarkHorse's new venue, and to give myself a chance to learn how to embed a Rumble video here, the following is the Q&A session from Podcast #175.

Embedding the video turned out go be easy enough, but I haven't yet figured out how to specify beginning and ending times. So I'll just mention that the section from 12:47 to 31:10, where Bret and Heather deal with the subject of childhood vaccinations, is particularly profitable. It may lead some of my readers to realize how insightful they themselves were many long years ago.

Heather's brief environmental rant from 1:11:35 to 1:12:45 is also worth listening to.

Permalink | Read 1241 times | Comments (0)

Category Politics: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Computing: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Children & Family Issues: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Random Musings: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Conservationist Living: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Inspiration: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] YouTube Channel Discoveries: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

As part of my ongoing project to organize and pare down my files (physical and digital) to something understandable to someone other than me (i.e. my heirs), I've been coming across many interesting glimpses of history. I try not to read more than a very small fraction of these, for the sake of making progress, but every once in a while something catches my eye.

We discovered e-mail long before 1993, but this is the oldest reference I've found so far.

GE Electronic Mail

To: W.LANGDON

Sub: Saturday, 30 January 1993This is a test of GEnie on our new machine! Our new tape drive

appears to be a good one. I backed up the hard drive, Porter

repartitioned it into three drives, including a small one just for

Aladdin. (This is so if Aladdin crashes and fouls up our file

allocation tables, it doesn't mess up the rest of our stuff.) We

moved Aladdin and associated files this afternoon. It appears to

work and it's even in color!

Some of you may be wondering what our "new machine" was.

In November of 1992, we ordered a "Gateway 2000 clock-doubled 66 MHz 486 machine" (original cow boxes!), with

- 200 Mb hard drive

- 1.44 Mb 3 1/2 inch drive

- 1.2 Mb 5 1/4 drive

- 120 Mb streaming tape drive for backup

- 8 Mb of memory

- 14-inch color SVGA monitor

- 33 MHz local bus

- and a tower case with one expansion slot reserved for CD-ROM. "CD-ROM technology is supposed to make major improvements shortly, so, while it is very attractive, we’re waiting on that one."At

At the time, I wrote the following.

It completely amazes me how much you can get for relatively little money these days. Total cost, including shipping: $3115. I know, that hardly seems “little,” but you have to remember that we once spent $1500 for an Intecolor graphics terminal, and then later had it repaired for $900! And that was when $2400 was worth a lot more than it is now. And our 14-year-old printer cost us $800. I’d really like a new printer, since with the Epson we can’t take advantage of a lot of what the new machines and software can do, and people are more and more frowning on dot-matrix letters. But I have to respect a piece of computer equipment that’s that old and still working as well as the day we got it!

Inflation calculators vary, but most put the cost of that 1993 machine at about $6650 in today's dollars. And our dot-matrix printer? $3300! This is not even attempting to take into account the difference in computing power between then and now. What really blows me away is that the $2400 we paid for the color terminal and its subsequent repair works out to nearly ten grand!

We were normally very good about sticking to a lean budget, but since computing was both vocation and avocation for each of us, well.... All I can say is that it's a good thing we were otherwise quite self-controlled in our spending. When it came to computing equipment, we had colleagues who were even more free-spending than we were—disproportionate to other areas of life. I guess it was the nature of the new, exciting field.

I'm going to have to remember this when it comes time to buy a new computer or a new phone.

A liberal Democrat Constitutional lawyer speaks on why everyone should be concerned about illegal behavior on the part of the FBI, and why he's involved in a lawsuit against "his own" party's actions. The video is long (26 minutes), and more relevant at the beginning than the end. You can get a good summary at about minutes 13-17. Or just this:

The Constitution is not only for people you agree with; it's primarily designed to protect people you disagree with, people whose views are out of fashion, people who everybody wants to see prosecuted.... I'm going to especially, especially, focus on people who are having their Constitutional rights violated by my political party, by my people who I voted for ... that's the special obligation that every citizen has to hold to account those who are on your side.

Also, look at about minutes 5-10, covering search warrants, and the dangers of having our whole lives on our cell phones. One day, out of the blue, we may find government officials seizing our phones, and our computers, and our external drives, ruining our businesses and even our lives in ways that cannot be redressed, even if we are eventually vindicated in court. So it behooves us to be grateful for those lawyers and politicians who seek to enforce strict Constitutional limits on when and how that is allowed—even against the most heinous people. (Cue the A Man for All Seasons devil and the law speech.)

Also, who knew (about 8:30-9:15) that it's safer—from the point of view of privacy—to store medications in a medicine cabinet rather than in a drawer?

It began a month ago, when we made the decision to switch our phones from AT&T to Spectrum. Spectrum is our cable internet provider, and now offers mobile phone service, which through some sleight of hand is actually Verizon.

We had been loyal AT&T customers all our long lives, from back when "Ma Bell" was the only way to go for long distance; through the forced breakup of AT&T that led to our move to Florida in the mid-1980's and Porter's 17 years of employment with the company; to our very first cell phone ("car phone") in the early 90's, and many changes of phones and phone service since—wherever we were, whatever our phones, it was all AT&T. I do know that there's really nothing left of the original AT&T besides the name, but still, it hurt to leave.

But recently we had two very annoying and expensive experiences with AT&T:

- "I don't care what the e-mail we sent you says, our system says differently so we're not going to honor the deal you signed up for."

- "Whatever made you think that making a call using Wi-fi Calling would not cost an arm and a leg when calling Switzerland?")

When these were quickly followed by

- A shockingly high price increase,

that was it for the camel's back. Spectrum/Verizon offered a price/service combination that was such an improvement we decided it was worth trying.

However, our AT&T root system was apparently stronger than we knew.

We made the account switch with ease, or so it seemed. When our new SIM cards arrived from Spectrum, Porter's phone made the switch without a hitch. My phone, on the other hand....

As I powered my phone back on after inserting the new SIM card, the phone insisted that I enter an unlock code. This was a bit concerning, as the phone was supposed to have been unlocked already. Thus began more than three weeks of struggle (mostly Porter's heroic work) with AT&T, Spectrum, and Samsung.

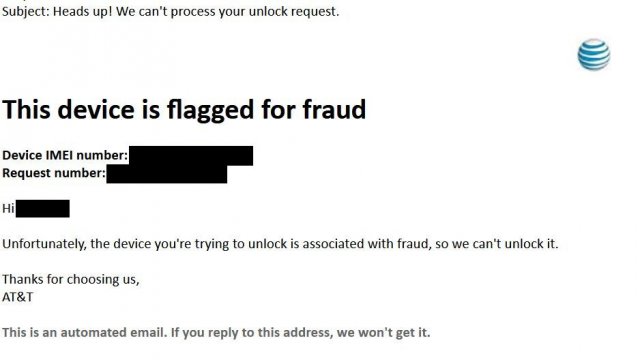

We tried multiple times to unlock the phone using AT&T's website. A few days after each try, we'd get an e-mail telling us there was a problem.

Next level: phone calls. Many phone calls, countless hours. Each time we'd be assured that an unlock code would come by e-mail "in a few days." Each time the result was failure.

By this time, we were on vacation in Connecticut, thankful to have one working phone as we continued the adventure. Hoping that being physically present might move things along, we took my phone to the local AT&T store. Although the sales clerk was friendly and tried to help, there wasn't much he could do as a simple reseller of AT&T services. So he sent us to a true AT&T store, half an hour down the road in Branford. As we drove along, we tried another phone call, ending up on hold for about an hour and a half in total, before giving up.

The Branford guy started our visit optimistically: "I can fix anything." Before we were done he'd gone so far as to drag the District Manager from another store out of a meeting to help. She was able to confirm that there was absolutely no reason we shouldn't be able to unlock the phone, and she said it shouldn't be necessary for us to drive to her store. We were grateful, as it was at that point rush hour, which in New Haven is nothing to be trifled with, and would have more than doubled the nominal 20-minute drive time. She escalated our problem up to highest priority, and we left the store armed with her telephone number.

Unfortunately, in the end, even that came to nothing. We went home to Florida.

Several more phone calls and no progress later, we learned that, while our problem was stilll "highest priority," it no longer had a person attached to it but had been kicked back to being assigned to a group. Knowing AT&T's trouble ticketing system from the inside out, Porter recognized this as the place insoluble problems are sent to die.

I'm half convinced the various companies hired someone's creative writing class to invent the reasons why they couldn't give me an unlock code.

- (AT&T) "Something went wrong, try again."

- (AT&T) "We can't give you a code because we can't get one from Samsung."

- (Samsung) "We can't give you a code because we don't do that; the code has to come from the carrier." (True, but it turns out that there is actually a code that must come from the manufacturer to the carrier, first.)

- (Samsung) "We can't give you a code because you bought the phone directly from us and all our phones ship unlocked already." (True, though it appears AT&T subsequently locked it, because we paid for it through our AT&T bill.)

- (AT&T) "We can't give you a code because your phone is already unlocked." (That's what their system kept telling them, but it was clearly untrue.)

- (Spectrum) "We can't help you because it was locked by AT&T."

- (AT&T) "Success! Here's your unlock code." That might have been encouraging, except that the code was simply "0." Right. An unconvincing null. With infinitesimal faith that it would work, we used up two of the five allowed attempts (after which the phone would become "permanantly locked") trying both a simple 0 and enough 0's to fill in the requested number of digits. As expected, it didn't work.

My all-time favorite of their excuses I reproduce below:

What on earth was the problem? We had bought the phone new, directly from Samsung, and it's hardly been out of my presence ever since. For a long time, this one had me looking over my shoulder for the FBI. Hey, if they can raid the private residence of a former U.S. president on the flimsiest of excuses, what chance do the rest of us have? Are they still mad about the grainy picture of Osama bin Laden that so annoyed Facebook?

After learning that there was little to no chance of our problem getting out of the trouble ticket graveyard, Porter employed a different tactic, one I would have given no chance at all of making any difference: He filed a complaint with the Federal Communications Commission.

Have you ever wondered if governmental agencies actually do anything to earn their tax dollars? In this case, Porter's complaint generated near-immediate action, first by the FCC itself and then by AT&T.

I'm not kidding: in a very short time he received both an e-mail and a phone call from the office of the president. (Of AT&T, that is, not Joe Biden.) A friendly and competent-sounding person promised to see what she could do.

At this point we began seriously debating how we would proceed if AT&T decided they were spending 'way too much money on this problem and offered to give us a new phone instead. It was not an easy decision. The lower-level folks who had no power to do so were, of course all in favor of giving away a phone. The mid-level folks grudgingly acknowledged that it might be a possibility, but only if I turned over my phone to them first. There was absolutely no way that was going to happen; my phone was not going to leave my possession until I had a working replacement with all my settings, apps, and data successfully transferred. Maybe they would be willing to send the new phone to our local AT&T store until we could successfully make the switch.

Then there was the problem of which phone? I didn't expect an upgrade to a more current phone: my Galaxy S9, even though it was the lastest thing in 2018, is now so old it's almost useless as a trade-in. I'd have been happy with a new S9, but do they even have any of those hanging around? Would I be offered a used, reconditioned phone, and would I be okay with that?

As it turned out, all that speculating was unnecessary. In only a few days, Porter received an e-mail with a non-zero unlock code.

Not without some trembling, we carefully, step by step, followed the instructions and entered the code into my mobile phone.

I have a working, Spectrum-serviced, cell phone.

A small part of me is reluctant to admit that. It was surprisingly easy to get along for nearly a month without one. Certainly it helped that I could do almost anything I wanted to with my phone, as long as I had wi-fi, which these days is nearly ubiquitous, even here.

I only missed a couple of things:

- The ability to make non-911 phone calls. (All phones work for emergencies, or so my phone told me.) If I were designing something named "Wi-Fi Calling," it would work using wi-fi when one does not have cell service. I mean, otherwise, what's the point? Especially if carriers are going to charge the same price as for regular cell calls (see above). But I wasn't the designer on that one. Even though I drove for decades without having cell service, I couldn't drive this past month without being aware of the lack.

- The ability to send and receive texts. That, too, should be possible over wi-fi.

Grateful as I am to have a fully-functioning phone, I have to say that a month without phone calls and texts was not all bad, It was rather nice, in fact—especially during political season.

Many thanks to all those ordinary people at AT&T and other places who were friendly and cheerful, and truly seemed to be doing what they could to help us. And deep gratitude to the one person at AT&T who somehow cut through the nonsense and got the job done. As Porter said in his thank you note to her, "If everyone at AT&T were as effective as you are, we'd still be customers."

I didn't choose Google Chat.

I still have one friend with whom I communicate by what was once known as Instant Messaging. Over the years, we have periodically been forced to change IM clients, and we mostly just go with the flow. (It was one such change that required me to get a Gmail address, which I had been resisting.)

The most recent change came when Google announced that Hangouts was being phased out in favor of Google Chat. I didn't complain too much, because they clearly had not been supporting Hangouts for a while—it would routinely crash on me several times during a half-hour conversation.

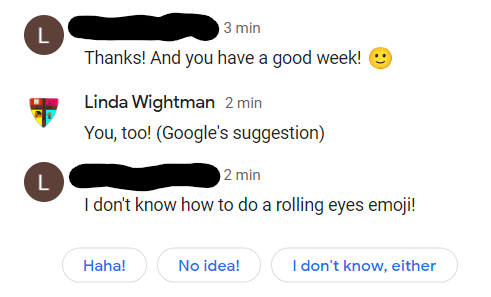

But Google Chat is creepy. (Just one in a long line of new tech creepiness.) When my friend enters a line, Chat usually pops up suggested responses for me, clearly based on what my friend has just said—possibly even on an analysis of the whole conversation. And quite accurately, I might add. Perhaps worse than the eavesdropping itself is that on the recipient's end, there is no indication that I did not type the response myself.

Here's what it looks like. I added the "(Google's suggestion)" after clicking the "You, too!" button presented to me.

My friend's version of Chat (or maybe she's still on Hangouts) does not yet have this feature, but she says it happens on her phone when texting. In the future shall we stop thinking at all and just let the AI control the conversation? Perhaps if I were having this conversation on my phone I might appreciate these shortcuts more, since I loathe what passes for typing on the phone. But here on my computer I can type nearly as fast as I can speak, so I'd rather use my own words, thank you.

I have no illusions that many of my readers will watch this video. Maybe no one at all. It's two hours long, and few of us have two hours to spare for a YouTube video. It's a discussion of human trafficking among David Freiheit (Viva Frei), Robert Barnes, and their guest, Eliza Bleu, a trafficking survivor and advocate. I managed to listen to it all by taking it in small bites and multitasking. Lengthy or not, the topic is important. They don't even try to deal with the more nuanced issues, such as "sex workers" whose participation is really, truly, consensual, and "slave wages" that turn out to be a family's best hope of escaping poverty. They don't even take on "legitimate pornography."

Sadly, I think this is a wise approach, if they don't want to make the mistake abortion opponents made: in that debate, too many people insisted on all-or-nothing, refusing to accept compromises that would have allowed abortions for cases of rape, incest, and where the child is so deformed that he would suffer and die soon after birth anyway. That approach was logical, in a theoretical, ethical sense—but arguing over the rare exceptions resulted in the door for abortion being opened wide and far. In the case of human trafficking, there is more than enough horror on which everyone but the perpetrators can agree; let's focus on that.

The interview is interesting from beginning to end, though that is a very poor word to describe something that can only be endured through a certain numbness and keeping the whole topic at a deliberate distance. The beginning, where Eliza tells her own story, is most interesting, especially to homeschoolers. If you're looking for another reason to hate the big social media companies, there's plenty of fodder in the later part of the video.

I'm frustrated that video is the medium of choice for so much information, especially current stories. I read so very much faster than I can listen, even pushing the video to higher speeds. Plus, anything good that is written has been through at least minimal editing, whereas with interviews, podcasts, and live streams, every um, uh, and rabbit trail remains. I find the written word to be much more efficient, usually much more dense in terms of information conveyed. But sometimes the more personal touch that can come through in a video is valuable, too.

In any case, as our choir director has taught us, it is what it is, and sometimes you have to adapt. I put this out here, (1) so I can find it again, and (2) in the off chance that someone may find it enlightening.

For the record, I decided to stop using my Fitbit at least a week before they announced the sell-out to Google.

First, it started acting erratically. Twice I thought I had lost it forever, which happened because I grew tired of wearing it on my wrist, and began keeping it in my pocket or purse. But each time, I managed to find it again, and what's more it started working better. However, the die was cast. Having had to face the prospect of no longer having my Fitbit, I decided that after two and a half years I'd already gained about as much as I was going to, in the form of new habits and awareness. Continued use had become more annoying than helpful.

Thus last Thursday, when I received an e-mail from them with the subject line, "Fitbit Joins Google," I knew I had made the right decision. See my recent post, "Big Tech, Big Brother."

It's only one small step. Google, Facebook, and Microsoft still own far too much of my life. As always, the goal is to minimize the damage without totally cutting off the benefits. How long can I ride the wave without drowning?

Permalink | Read 1608 times | Comments (0)

Category Health: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Politics: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Computing: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Social Media: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

I've never liked Apple. No, that's not true. A very long time ago, in a small room at the University of Rochester's Goler House, we were treated by Byte magazine editor Carl Helmers to a preview of the "Apple 1" computer. As I recall it was a prototype, not much more than a circuit board attached to a cassette tape recorder. We were blown away and walked out of that room with a strong desire to invest. Alas, that was not possible. When Apple finally went public, it was already popular and far too late to get in on the ground level.

That meeting was the last time I liked Apple: I've since been turned off by their "our way or the highway" attitude and what I considered to be strong-arm tactics. I miss the early days of personal computing, where there was lots of competition. It wasn't long, however, before Microsoft became Apple's only reasonable competitor, and started using strong-arm tactics of its own.1

To take just one example: WordPerfect had long been my word processor of choice—indeed, it was the first to have that name, rather than "text editor," and I was thrilled. That's when the writer in me really began to take off. I had no reason to leave it, except that Microsoft's Word took over the world, and I adjusted to the switch. I still like most of Microsoft Office, though I've seen no reason to advance beyond the 2010 version. But eventually I tired of putting all my eggs in one basket, especially since Microsoft was moving to a subscription form of Office, which I had no intention of buying into.

So what did I do? I began the process of moving most of my work to Google Docs and Google Sheets. If they didn't have everything I liked about the Microsoft versions, they were good enough. And it was handy to have everything accessible and shareable online.

Ah, but it is Google. The little underdog I had enthusiastically supported last century has become a monolith. The wild-and-crazy upstart has become The Man. I'd had warnings before that it was not what it appeared to be, thanks to some inside information from a friend of a Google employee. But it was when they took over YouTube that I really started to dislike Google. Not for any particular reason, but simply because it gave them still more power.

Once upon a time there were many social media platforms. Now Facebook, Twitter, and Google (through YouTube) control and define the world. I've never been all that upset about what they call Big Data. It's mostly seemed about advertising, and I'm fairly resistent to that. But now it's beginning to feel more sinister, and I realize that with the kind of power that amount of data confers, there's a lot more at stake than my puny purchasing power.

Short of physical superiority (think being on the wrong end of a gun barrel) or spiritual authority (think being on the wrong side of someone you believe has the power to condemn you to hell), is there any more dangerous display of raw power than the control of information? Is there anything more dangerous to those in power than free access to information? Ask the Catholic Church what the printing press did for Martin Luther and the Protestant Reformation. Ask our Founding Fathers how the written word fueled the American Revolution. Consider the effect of Twitter and cell phones on the Arab Spring. Now, in the Information Age, it is more true than ever that Knowledge is Power. And he who controls the availability of knowledge controls us all.

I know there must be limits to First Amendment freedom of speech. The classic example is that we are not free to shout "Fire!" in a crowded theater. I personally think "freedom of speech" is severely degraded when it is used to justify cross-burning, flag-burning, and obscene and/or hateful art and literature, though there's a long history of acceptance of that argument. What is arising now, however, is something much bigger and much more dangerous: suppression of reasoned, rational political speech, with the Powers that Be setting themselves up not only as the arbiters of what thoughts are allowed to be expressed, but specifically of what is truth. Whether these Powers are a repressive government, a monopolistic educational system, media outlets that conflate fact and editorial opinion, or an oligarchy of information technology companies, we've moved into the Red Alert zone.

It takes a certain amount of courage to give people the power to sift through competing ideas and make up their own minds about an issue, but it is the price of freedom.

David Freiheit is my new favorite Canadian lawyer.2 He makes legal issues more understandable; I love hearing a Canadian perspective, especially on American politics; and he's usually calm and reasonable. I like what he has to say about this issue in the following video. Start around 4:10.

If you give them the reaction [they are trying to provoke], all that you do is play exactly into ... their hand, and you in fact further aid them in the pursuance of their ultimate objective. There are ways to usefully protest and to usefully object, and there are ways to counter-productively object and counter-productively protest, and if one succumbs to the counter-productive methods of protest, not only are they going to be further from achieving their own goal, they're actually going to assist their adversary in achieving their goal. And that is something that too few people truly appreciate, is that it's not a question of rolling over and accepting the unacceptable; it's a question of fighting it in a useful manner that does not actually compromise your goals and further the goals that you don't agree with in the first place.

It's not a slippery slope; it's a free-fall.

Freiheit records his videos in some unusual places. In this one, he's ice fishing, and I kept getting distracted by the thought, "Aren't his hands freezing?"

1There are those who will insist that Linux remains a viable, independent choice. But practically speaking, for most of us, it's too technical to bother with.

2I recommend many of Freiheit's videos, but as with most online forums, from YouTube to our local newspaper, I recommend avoiding the comments. Anywhere there are unmoderated comments, the crazies will come out.

Digital Minimalism: Choosing a Focused Life in a Noisy World by Cal Newport (Portfolio/Penguin 2019)

Digital Minimalism: Choosing a Focused Life in a Noisy World by Cal Newport (Portfolio/Penguin 2019)

Janet recommended this one to me, and after checking out Newport's TED talk, "Why You Should Quit Social Media," I decided to reserve it at the library. I had to wait in line; maybe more than a few people are rethinking Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, Old Uncle Tom Cobleigh and all.

Digital Minimalism is divided into two parts: Foundations, and Practices. I read through Foundations easily, able to enjoy the book without pasting sticky tabs all over it. For me, this is like going somewhere and not taking pictures. Those sticky notes represent text that I will later laboriously transcribe for my reviews. As with the photos, something is gained but something is lost. I was enjoying the book and anticipating an easy review.

Then I hit Practices. Or Practices hit me.

The first chapter of that section, "Spend Time Alone," is about solitude deprivation. I could have sticky-noted the whole chapter. Here is me, restraining myself:

Everyone benefits from regular doses of solitude, and, equally important, anyone who avoids this state for an extended period of time will ... suffer. ... Regardless of how you decide to shape your digital ecosystem, you should give your brain the regular doses of quiet it requires to support a monumental life. (pp. 91-92).

[Raymond] Kethledge is a respected judge serving on the United States Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit, and [Michael] Erwin is a former army officer who served in both Iraq and Afghanistan. ... [Their book on the topic of solitude], Lead Yourself First ... summarizes, with the tight logic you expect from a federal judge and former military officer, [their] case for the importance of being alone with your thoughts. Before outlining their case, however, the authors start with what is arguably one of their most valuable contributions, a precise definition of solitude. Many people mistakenly associate this term with physical separation—requiring, perhaps, that you hike to a remote cabin miles from another human being. This flawed definition introduces a standard of isolation that can be impractical for most to satisfy on any sort of a regular basis. As Kethledge and Erwin explain, however, solitude is about what’s happening in your brain, not the environment around you. Accordingly, they define it to be a subjective state in which your mind is free from input from other minds. (pp. 92-93)

You can enjoy solitude in a crowded coffee shop, on a subway car, or, as President Lincoln discovered at his cottage, while sharing your lawn with two companies of Union soldiers, so long as your mind is left to grapple only with its own thoughts. On the other hand, solitude can be banished in even the quietest setting if you allow input from other minds to intrude. In addition to direct conversation with another person, these inputs can also take the form of reading a book, listening to a podcast, watching TV, or performing just about any activity that might draw your attention to a smartphone screen. Solitude requires you to move past reacting to information created by other people and focus instead on your own thoughts and experiences—wherever you happen to be. (pp. 93-94).

Regular doses of solitude, mixed in with our default mode of sociality, are necessary to flourish as a human being. It’s more urgent now than ever that we recognize this fact, because ... for the first time in human history solitude is starting to fade away altogether. (p. 99)

The concern that modernity is at odds with solitude is not new. ... The question before us, then, is whether our current moment offers a new threat to solitude that is somehow more pressing than those that commentators have bemoaned for decades. ... To understand my concern, the right place to start is the iPod revolution that occurred in the first years of the twenty-first century. We had portable music before the iPod ... but these devices played only a restricted role in most people’s lives—something you used to entertain yourself while exercising, or in the back seat of a car on a long family road trip. If you stood on a busy city street corner in the early 1990s, you would not see too many people sporting black foam Sony earphones on their way to work. By the early 2000s, however, if you stood on that same street corner, white earbuds would be near ubiquitous. The iPod succeeded not just by selling lots of units, but also by changing the culture surrounding portable music. It became common, especially among younger generations, to allow your iPod to provide a musical backdrop to your entire day—putting the earbuds in as you walk out the door and taking them off only when you couldn’t avoid having to talk to another human. (pp. 99-100).

This transformation started by the iPod, however, didn’t reach its full potential until the release of its successor, the iPhone.... Even though iPods became ubiquitous, there were still moments in which it was either too much trouble to slip in the earbuds (think: waiting to be called into a meeting), or it might be socially awkward to do so (think: sitting bored during a slow hymn at a church service). The smartphone provided a new technique to banish these remaining slivers of solitude: the quick glance. (p. 101)

When you avoid solitude, you miss out on the positive things it brings you: the ability to clarify hard problems, to regulate your emotions, to build moral courage, and to strengthen relationships. (p. 104)

Eliminating solitude also introduces new negative repercussions that we’re only now beginning to understand. A good way to investigate a behavior’s effect is to study a population that pushes the behavior to an extreme. When it comes to constant connectivity, these extremes are readily apparent among young people born after 1995—the first group to enter their preteen years with access to smartphones, tablets, and persistent internet connectivity. ... If persistent solitude deprivation causes problems, we should see them show up here first. ...

The head of mental health services at a well-known university ... told me that she had begun seeing major shifts in student mental health. ... Seemingly overnight the number of students seeking mental health counseling massively expanded, and the standard mix of teenage issues was dominated by something that used to be relatively rare: anxiety. ... The sudden rise in anxiety-related problems coincided with the first incoming classes of students that were raised on smartphones and social media. She noticed that these new students were constantly and frantically processing and sending messages. ...

[San Diego State University psychology professor Jean Twenge observed that] young people born between 1995 and 2012 are ... on the brink of the worst mental-health crisis in decades. ... [She] made it clear that she didn’t set out to implicate the smartphone: “It seemed like too easy an explanation for negative mental-health outcomes in teens,” but it ended up the only explanation that fit the timing. Lots of potential culprits, from stressful current events to increased academic pressure, existed before the spike in anxiety.... The only factor that dramatically increased right around the same time as teenage anxiety was the number of young people owning their own smartphones. ...

When journalist Benoit Denizet-Lewis investigated this teen anxiety epidemic in the New York Times Magazine, he also discovered that the smartphone kept emerging as a persistent signal among the noise of plausible hypotheses. “Anxious kids certainly existed before Instagram,” he writes, “but many of the parents I spoke to worried that their kids’ digital habits—round-the-clock responding to texts, posting to social media, obsessively following the filtered exploits of peers—were partly to blame for their children’s struggles.” Denizet-Lewis assumed that the teenagers themselves would dismiss this theory as standard parental grumbling, but this is not what happened. “To my surprise, anxious teenagers tended to agree.” A college student he interviewed at a residential anxiety treatment center put it well: “Social media is a tool, but it’s become this thing that we can’t live without that’s making us crazy.” (pp. 104-107)

The pianist Glenn Gould once proposed a mathematical formula for this cycle, telling a journalist: “I’ve always had a sort of intuition that for every hour you spend with other human beings you need X number of hours alone. Now what that X represents I don’t really know . . . but it’s a substantial ratio.” (p. 111)

The past two decades ... are characterized by the rapid spread of digital communication tools—my name for apps, services, or sites that enable people to interact through digital networks—which have pushed people’s social networks to be much larger and much less local, while encouraging interactions through short, text-based messages and approval clicks that are orders of magnitude less information laden than what we have evolved to expect. ... Much in the same way that the “innovation” of highly processed foods in the mid-twentieth century led to a global health crisis, the unintended side effects of digital communication tools—a sort of social fast food—are proving to be similarly worrisome.(p. 136).

After winning me over with the chapter on solitude deprivation, Newport lost me somewhat with his approach to taming the beasts. The basic problem is that, for a guy who has written several books and has his own blog, he seems to have very little respect for the written word.

Many people think about conversation and connection as two different strategies for accomplishing the same goal of maintaining their social life. This mind-set believes that there are many different ways to tend important relationships in your life, and in our current modern moment, you should use all tools available—spanning from old-fashioned face-to-face talking, to tapping the heart icon on a friend’s Instagram post.

The philosophy of conversation-centric communication takes a harder stance. It argues that conversation is the only form of interaction that in some sense counts toward maintaining a relationship. This conversation can take the form of a face-to-face meeting, or it can be a video chat or a phone call—so long as it matches Sherry Turkle’s criteria of involving nuanced analog cues, such as the tone of your voice or facial expressions. Anything textual or non-interactive—basically, all social media, email, text, and instant messaging—doesn’t count as conversation and should instead be categorized as mere connection. (p. 147)

I heartily disagree with his lumping e-mail in with "all social media, text, and instant messaging." I will grant that most social media, texts, WhatsApp, IM, and the like are severely limited by the difficulty of creating the message. Phones simply are not designed for high-speed typing, and I don't know about other people's experiences, but for me voice-to-text makes so many errors I spend almost as much time correcting as I would have laboriously pecking out a message on the tiny keyboard. (That's why I much prefer WhatsApp, where I can type my messages on the computer keyboard, to texting, where I can't.) So messages tend to be short, of restricted vocabulary and complexity, and full of nasty abbreviations. But e-mails are simply typed letters that get delivered with much more speed than the mail can achieve. I will grant that you miss the tone-of-voice cues that can be heard over the phone, but I think that's often more than made up for by the ability to both speak and listen without interruption. On the phone, if I turn all my attention to what the other person is saying, there's a long silence when it's my turn to talk while I think of how I want to respond. But if I try to figure that out while the other person is speaking, I'm likely to miss, or mis-interpret what is said. And when I'm speaking, it's more than likely that I will get interrupted before getting out my entire thought, and the conversation will veer off in another direction, leaving my response incomplete and likely mis-understood. E-mail leaves plenty of time for listening, thinking, and responding.

Newport has serious problems with Facebook's "Like" button. I can see his point in some respects.

The “Like” feature evolved to become the foundation on which Facebook rebuilt itself from a fun amusement that people occasionally checked, to a digital slot machine that began to dominate its users’ time and attention. This button introduced a rich new stream of social approval indicators that arrive in an unpredictable fashion—creating an almost impossibly appealing impulse to keep checking your account. It also provided Facebook much more detailed information on your preferences, allowing their machine-learning algorithms to digest your humanity into statistical slivers that could then be mined to push you toward targeted ads and stickier content. (p. 192)

I do get the slot-machine analogy. We all crave (positive) feedback for whatever of ourselves we have put "out there." And the temptation to keep checking is real. It reminds me of the joke from 'way back in the America Online days, in which the person sitting at the computer (no smart phones back then) checks his mail, sees that there is none waiting for him—and immediately checks again. It was funny because that's what so many people did. But I think Newport misunderstands how many of us use the Like button.

In the context of this chapter, however, I don’t want to focus on the boon the “Like” button proved to be for social media companies. I want to instead focus on the harm it inflicted to our human need for real conversation. To click “Like,” within the precise definitions of information theory, is literally the least informative type of nontrivial communication, providing only a minimal one bit of information about the state of the sender (the person clicking the icon on a post) to the receiver (the person who published the post). Earlier, I cited extensive research that supports the claim that the human brain has evolved to process the flood of information generated by face-to-face interactions. To replace this rich flow with a single bit is the ultimate insult to our social processing machinery. (p. 153)

But here's the thing. I don't know anyone who pretends that clicking "Like" or "Love" or "I care" is conversation. However, it is the digital equivalent of one part of a successful conversation: the nod, the smile, the grunt, the frown, the short interjection, which in face-to-face conversation we used as an important lubricant to keep a conversation running smoothly. It hardly communicates any more information than the Facebook buttons; maybe it's little more than a bit—but it's an important bit. It says, "I'm listening, I hear you, I agree, keep talking," or "Wait, what you said confuses me, or angers me," or "I'm sorry, I sympathize."

As soon as easier communication technologies were introduced—text messages, emails—people seemed eager to abandon this time-tested method of conversation for lower-quality connections (Sherry Turkle calls this effect “phone phobia”). (p. 160)

Guilty as charged, but there's no need for Newport (or Turkle) to be snarky about it. I'm hardly alone, and there's ample evidence that phone phobia is attached to the same set of genes that makes me like mathematics. I love the (true) story a colleague told of a bunch of math grad students who decided to order pizza. Every one of them hemmed and hawed and delayed making the order, until the wife of one of the mathematicians, herself a grad student in philosophy, sighed, "For Pete's sake!" and called the restaurant. Text-based communication is a real boon to people like us. Call it a disability if you like—and then remember that you shouldn't mock or discriminate against people with disabilities.

Fortunately, there’s a simple practice that can help you sidestep these inconveniences and make it much easier to regularly enjoy rich phone conversations. I learned it from a technology executive in Silicon Valley who innovated a novel strategy for supporting high-quality interaction with friends and family: he tells them that he’s always available to talk on the phone at 5:30 p.m. on weekdays. There’s no need to schedule a conversation or let him know when you plan to call—just dial him up. As it turns out, 5:30 is when he begins his traffic-clogged commute home in the Bay Area. He decided at some point that he wanted to put this daily period of car confinement to good use, so he invented the 5:30 rule. The logistical simplicity of this system enables this executive to easily shift time-consuming, low-quality connections into higher-quality conversation. If you write him with a somewhat complicated question, he can reply, “I’d love to get into that. Call me at 5:30 any day you want.” Similarly, when I was visiting San Francisco a few years back and wanted to arrange a get-together, he replied that I could catch him on the phone any day at 5:30, and we could work out a plan. When he wants to catch up with someone he hasn’t spoken to in a while, he can send them a quick note saying, “I’d love to get up to speed on what’s going on in your life, call me at 5:30 sometime.” ... He hacked his schedule in such a way that eliminated most of the overhead related to conversation and therefore allowed him to easily serve his human need for rich interaction. (pp. 161-162)

I have to say, that strikes me as more selfish than clever. It's saying to everyone else that he will only communicate with them through his own preferred medium. Granted, it's his right to do so, and maybe he's learned that that's the best way he can get the most accomplished. But I'd have to be pretty desperate to call someone who I knew was going to be driving while he is talking with me. Either he's not going to be giving me his full attention, or he's not going to be giving the other cars on the road his full attention, neither one of which strikes me as ideal. And if I have a complicated question, I definitely want the response to be by written word, where there's a record of what was said, and more chance of getting a well thought out response.

I’ve seen several variations of this practice work well. Using a commute for phone conversations, like the executive introduced above, is a good idea if you follow a regular commuting schedule. It also transforms a potentially wasted part of your day into something meaningful. Coffee shop hours are also popular. In this variation, you pick some time each week during which you settle into a table at your favorite coffee shop with the newspaper or a good book. The reading, however, is just the backup activity. You spread the word among people you know that you’re always at the shop during these hours with the hope that you soon cultivate a rotating group of regulars that come hang out. ... You can also consider running these office hours once a week during happy hour at a favored bar. (pp. 162-163)

<Shudder> Really? I'm supposed to go to the expense, inconvenience, and annoyance of sitting around at a coffee shop or bar on spec, just hoping a friend shows up? And expect my friends to be willing to pay an insane amount for a cup of coffee just to talk with me? Here, and in many other places in Digital Minimalism, you can tell that Newport is an extrovert—with plenty of spare cash—and friends who are the same.

And anyway, whatever happened to visiting people in their homes? One friend of ours decided to quit Facebook, and in her final message invited anyone in town to drop by her house for tea. I could get into that. If you're willing to get out and drive to a restaurant, come instead and knock at our door. You'll be more than welcome and none one of us will have to buy an expensive drink. (This pandemic won't last forever.)

[In the early 20th century, Arnold Bennett, author of How to Live on 24 Hours a Day, speaking of leisure activities] argues that these hours should instead be put to use for demanding and virtuous leisure activities. Bennett, being an early twentieth-century British snob, suggests activities that center on reading difficult literature and rigorous self-reflection. In a representative passage, Bennett dismisses novels because they “never demand any appreciable mental application.” A good leisure pursuit, in Bennett’s calculus, should require more “mental strain” to enjoy (he recommends difficult poetry). (p. 175)

Newport approves of the idea that "the value you receive from a pursuit is often proportional to the energy invested." But then he adds,

For our twenty-first-century purposes, we can ignore the specific activities Bennett suggests. (p. 175)

And what, pray tell, is snobbish or unreasonable about literature and poetry?

Newport has a lot to say about the value of craft: of woodworking, or renovating a bathroom, or repairing a motorcycle, or knitting a sweater. He includes musical performances as well. But—and I find this odd for an author—he seems to have little respect for creating books. Would it be a more noble activity if they were typed on an old Remington, or handwritten? He similarly discounts composing music using a computer as less worthwhile than playing a guitar. I don't buy it.

The following story is for our two oldest grandsons, who have a way of picking up and enjoying construction skills.

[Pete's] welding odyssey began in 2005. At the time, he was building a custom home. ... The house was modern so Pete integrated some custom metalwork into his design plan, including a beautiful custom steel railing on the stairs.

The design seemed like a great idea until Pete received a quote from his metal contractor for the work: it was for $15,800, and Pete had budgeted only $4,000. “If this guy is billing out his metalworking time at $75.00 an hour, that’s a sign that I need to finally learn the craft myself,” Pete recalls thinking at the time. “How hard can it be?” In Pete’s hands, the answer turned out to be: not that hard.

Pete bought a grinder, a metal chop saw, a visor, heavy-duty gloves, and a 120-volt wire-feed flux core welder—which, as Pete explains, is by far the easiest welding device to learn. He then picked some simple projects, loaded up some YouTube videos, and got to work. Before long, Pete became a competent welder—not a master craftsman, but skilled enough to save himself tens of thousands of dollars in labor and parts. (As Pete explains it, he can’t craft a “curvaceous supercar,” but he could certainly weld up a “nice Mad-Max-style dune buggy.”) In addition to completing the railing for his custom home project (for much less than the $15,800 he was quoted), Pete went on to build a similar railing for a rooftop patio on a nearby home. He then started creating steel garden gates and unusual plant holders. He built a custom lumber rack for his pickup truck and fabricated a series of structural parts for straightening up old foundations and floors in the historic homes in his neighborhood. As Pete was writing his post on welding, a metal attachment bracket for his garage door opener broke. He easily fixed it. (pp. 194-195)

If you're wondering where to learn skills needed for simple projects ... the answer is easy. Almost every modern-day handyperson I've spoken to recommends the exact same source for quick how-to lessons: YouTube. (pp. 197-198, emphasis mine)

In the middle of a busy workday, or after a particularly trying morning of childcare, it’s tempting to crave the release of having nothing to do—whole blocks of time with no schedule, no expectations, and no activity beyond whatever seems to catch your attention in the moment. These decompression sessions have their place, but their rewards are muted, as they tend to devolve toward low-quality activities like mindless phone swiping and half-hearted binge-watching. ... Investing energy into something hard but worthwhile almost always returns much richer rewards. (p. 212)

Finally, I can't resist his description of former Kickstarter project called the Light Phone.

Here’s how it works. Let’s say you have a Light Phone, which is an elegant slab of white plastic about the size of two or three stacked credit cards. This phone has a keypad and a small number display. And that’s it. All it can do is receive and make telephone calls—about as far as you can get from a modern smartphone while still technically counting as a communication device.

Assume you’re leaving the house to run some errands, and you want freedom from constant attacks on your attention. You activate your Light Phone through a few taps on your normal smartphone. At this point, any calls to your normal phone number will be forwarded to your Light Phone. If you call someone from it, the call will show up as coming from your normal smartphone number as well. When you’re ready to put the Light Phone away, a few more taps turns off the forwarding. This is not a replacement for your smartphone, but instead an escape hatch that allows you to take long breaks from it. (p. 245).

Despite our areas of disagreement, there's only one really, really annoying section of the book. He spends seven pages on the ideas of someone named Jennifer who "prefers the pronoun 'they/their' to 'she/her'." The ideas are not worth the ensuing confusion between singular and plural. I found myself constantly re-reading trying to figure out who was being referenced in the text.

But I do recommend reading Digital Minimalism. The concept of solitude deprivation alone would make it worthwhile, and the rest of the book is pretty good, too—especially if you're not a phone-phobic, introverted author.

Permalink | Read 2275 times | Comments (6)

Category Reviews: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Education: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Health: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Computing: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Children & Family Issues: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Social Media: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

Hey, Boomer! Would you process my unemployment claim, please?

At first I thought the headline was a joke: Wanted urgently: People who know a half century-old computer language so states can process unemployment claims.

On top of ventilators, face masks and health care workers, you can now add COBOL programmers to the list of what several states urgently need as they battle the coronavirus pandemic.

In New Jersey, Gov. Phil Murphy has put out a call for volunteers who know how to code the decades-old computer programming language called COBOL because many of the state's systems still run on older mainframes.

My programming languages from back in the day inluded FORTRAN, PL/1, ALGOL, LISP, BASIC, and assembly language for Linc-8, PDP-12 (machine language for these two as well), and PDP-11. I didn't learn COBOL because that was considered a business language (COmmon Business-Oriented Language) and I worked on the scientific side of things. But it appears to have had remarkable staying power, and Porter knew it well. Not that I see him going to New Jersey anytime soon.

"The general population of COBOL programmers is generally much older than the average age of a coder... Many American universities have not taught COBOL in their computer science programs since the 1980s."

So, Boomers to the rescue. It pays to keep people with arcane knowledge around.

I predict that someday we will regret letting our amateur radio network fall apart.

Ya'll know how much I dislike shopping. But I made a purchase the other day that was pure delight.

I bought a mouse.

Not the kind that Elbereth—our grandson's California king snake—would like to eat, but a replacement for my computer mouse. I'd been living for quite a while with its reluctance to register clicks properly, but then its scrolling started acting up. I even lived with that for a while—I'm always too ready to believe that the problem must somehow be my fault, or a temporary glitch, or anything else that lets me avoid having to shop for something new.

But when it started not scrolling at all, and replacing the battery didn't help, I reluctantly headed to the Best Buy website. And what to my wondering eyes should appear, among all the mouse choices, but the very same model mouse that was failing me, the one that I really like and had served me well for many, many years.

Thirty years ago that wouldn't have surprised me. Now, however, I find that when it's time to replace an item, it's no longer sold. Shoes, jeans, bras, mixers, computers, software.... You name it, most of the time I am not looking to replace my worn-out item with something "new and improved," but rather with the same thing that has served me well and requires no learning curve—but in working condition. And most of the time I fail in my endeavour.

Not this time. Could I have found a better mouse? Could I have found a less expensive mouse? Perhaps. But I bought it then and there, and picked it up the next day at the Best Buy down the street. I installed the battery, plugged it into my computer, and was able to continue working with no more thought than how nice it was that my clicks and scrolling were now dependable. I consider that $20 very well spent.

If only I could achieve the same success with my jeans. Even the pair I bought just a couple of years ago, and finally decided would be an acceptable substitute for my old favorites, is no longer sold.

I wonder if I should have bought two mice....

Promising, practical ... and, as with so many applications of massive data collection and analysis, maybe a little perturbing. This post is primarily for the materials scientist in the family, but it should be interesting to anyone.

Scientists at MIT and Berkeley, using Artificial Intelligence algorithms to pore over abstracts from papers related to materials science, have successfully predicted scientific discoveries.

Researchers from the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory used an algorithm called Word2Vec sift through scientific papers for connections humans had missed. Their algorithm then spit out predictions for possible thermoelectric materials. ... The algorithm didn’t know the definition of thermoelectric, though. It received no training in materials science. Using only word associations, the algorithm was able to provide candidates for future thermoelectric materials.

Using just the words found in scientific abstracts, the algorithm was able to understand concepts such as the periodic table and the chemical structure of molecules. The algorithm linked words that were found close together, creating vectors of related words that helped define concepts. In some cases, words were linked to thermoelectric concepts but had never been written about as thermoelectric in any abstract they surveyed. This gap in knowledge is hard to catch with a human eye, but easy for an algorithm to spot.

In one experiment, researchers analyzed only papers published before 2009 and were able to predict one of the best modern-day thermoelectric materials four years before it was discovered in 2012.

This new application of machine learning goes beyond materials science. Because it’s not trained on a specific scientific dataset, you could easily apply it to other disciplines, retraining it on literature of whatever subject you wanted.

Here's an article from MIT that's a bit more technical.

MIT and Berkeley may be doing this particular research, but anyone want to guess where the Word2vec algorithm was developed?

Google.

I have many sins on my conscience, but Evil E-mail Man proved that he was talking through his hat by choosing one that I know beyond the shadow of a doubt I have never committed.

Apparently, "I have a video of you screaming at your kids, and if you don't pay me a bunch of Bitcoin, I'll release it to all of your contacts" is not considered nearly as threatening as "I have a video of you visiting an internet porn site." But at least it would have been credible.

This blog is my storehouse for a good deal of miscellany, since combined with Google's search capabilities, it's a good way to find things at some future time when I've forgotten them, despite assurances to myself that of course I wouldn't forget that.

Smart Lock is a feature on the Galaxy S9 (and other phones too, I'm sure, but this is the one I know about) that allows me to lock my phone yet not have to deal with the inconvenience of unlocking it every time I pick it up. You tell the phone that certain places are trusted, such as home, and it won't require unlocking when you're in that place. Yay! It worked like a charm—for the first few days.

Then, as charms are wont to do, it became fickle. I found myself having to unlock my phone all the time. It was driving me up the wall. I tried this, that, and the other thing, all to no avail. Finally, I took the problem to Dr. Google. There I found a suggestion that the poster said was crazy, but effective:

I, like most people, had accepted the phone's suggestion of my home address for a trusted site. I don't know if it's Google's fault or something else, but people have found that to stop working after a few days, as it did for me. Who knows why? The secret, they said, was to edit the home location and move the marker a bit to reset it.

That didn't work for me. Perhaps I didn't move it enough, but since Google warned that doing so would affect the location of my home in several other of its applications, I didn't want to move it too much.

Instead, I took a different approach. I set up a second trusted site that was in the correct location, but not associated with my address—it's known to the system by its latitude and longitude. That worked perfectly.

Until it didn't, and I was back to having to unlock my phone every time.

I opened the SmartLock settings again, and added yet another trusted location—the place that my phone apparently thought it was, right then.

And that worked, until it didn't. The pattern seems to be this: For a day, my phone would stay unlocked. Sometimes I'd get more than one day out of it, but generally the next morning I'd wake up back at Square One.

Actually, not quite back to the beginning—I'm gradually accumulating a collection of trusted places around our house. Despite the fact that SmartLock claims to be trusting a fairly large circle around a given location, that's not they way it's acting. The trusted places on my list show differences by 0.1" in either latitude or longitude. I hoped that eventually I'd have all the bases covered....

I'm still hoping that, but it seems to be a very slow process. Apparently the latitude and longitude measurements have a finer granularity than what is displayed. The process I have settled into is this:

When I first open my phone in the morning, I must unlock it. That's what I would expect after a long pause in use. But then the next time I try to use it, the phone is locked again. So I go into the SmartLock settings and add a new trusted place—wherever the phone thinks it is. After that, the phone is good for the rest of the day. I must do this every day.

It's a pain, and it shouldn't be that way, but it works for me. For now. I'll update this if I ever figure out something better.

UPDATE 2/7/19 There is hope that my phone will eventually learn that our home is a safe place. Today began with the usual problem: I opened the phone and needed to unlock it. The same thing happened the second time, but I was too lazy to go through the process of adding a new Trusted Location. Somewhere along the line—third or fourth time, maybe?—the phone opened with no need for unlocking. Was that because I was at that point in a different room of the house, one the phone recognized? Who knows, but it gives me hope to keep observing and experimenting.

The infamous Blue Screen of Death is all too familiar to my generation of Windows users. It may be that blue screens are now causing death in a different way.

This Popular Science article reports that prolonged exposure to blue light can cause irreversible damage to the cells that allow us to see. (And truly, I thought of the Blue Screen of Death analogy before I noticed that the article's author did, too.) That would be light from our televisions, computers, phones, e-readers, and even increasingly popular LED illumination.

Catastrophic damage to your vision is hardly guaranteed. But the experiment shows that blue light can kill photoreceptor cells. Murdering enough of them can lead to macular degeneration, an incurable disease that blurs or even eliminates vision.

Blue light occurs naturally in sunlight, which also contains other forms of visible light and ultraviolet and infrared rays. But ... we don’t spend that much time staring at the sun. As kids, most of us were taught it would fry our eyes. Digital devices, however, pose a bigger threat. The average American spends almost 11 hours a day in front of some type of screen, according to a 2016 Nielsen poll. Right now, reading this, you’re probably mainlining blue light.

Obviously, more research is needed before we panic about this. But maybe it's time I stopped putting myself to sleep by reading on my Kindle, or playing a move or two in Word Chums, or praying through our church's Prayer Chain list. They say you should turn off "devices" an hour before bedtime, because the blue light can keep you from falling asleep. That's never been an issue for me. But damaging my eyes? That's a much bigger issue.